Proposal (420) to South American Classification Committee

Separate

Pseudocolopteryx flaviventris into

two species

Effect on South American CL: this proposal would add a new species to our list, Pseudocolopteryx citreola.

Background: There is almost no background on this; much of

it is new information. However, it bears noting that there are four species

presently in the genus Pseudocolopteryx.

On the whole they are a group with their center of abundance and diversity in

the southern cone, Argentina specifically. All are yellow below, and either

brownish, greenish, or olive above. Plumage differences among species are

slight, but vocally all can be distinguished (i.e. Bostwick & Zyskowski

2001). On the whole, taxonomy in this group has been stable - no great

upheavals or controversies have occurred.

One

other member of the genus was described from central Chile by Landbeck (1864),

as Arundinicola citreola. Wetmore (1926) mentioned and described citreola from Argentina as well, including

its voice. Later Hellmayr (1927) subsumed citreola

into flaviventris based on similarity

in plumage and measurements, although citreola

averages larger and longer-winged than flaviventris.

He did not give it subspecies status; the name essentially was then lost in the

literature and never heard from again.

New information: In the late 80s Bret Whitney was scouting for an upcoming

birding tour to Chile when he heard and tracked down an unknown song near

Renaico, in the Bio-Bio Region. The bird was recorded and observed and appeared

to be a Pseudocolopteryx, nearly

identical to flaviventris but with a

rather different song. This original recording was poor, but diagnostic, and

for many years was the only recording known of this population. Later Guillermo

Egli (2002) published a superb recording, which matches exactly the Renaico

bird. This second recording was made in the Valparaiso Region at the mouth of

the Maipo River. Later, Jaramillo was able to see and record this song type

both at the Renaico site, as well as the Maipo River site, in addition to the

Santa Inez marsh nearer to Santiago. Santa Inez is approximately 30 km from the

type locality of citreola along the

Mapocho River in the Metropolitan region. All Chilean birds sound exactly the

same and are quite different from true flaviventris

found in E. Argentina, Uruguay, and S. Brazil (see below).

Abalos

and Areta (2009) moved the discussion further. They published sonograms of citreola from Chile and Argentina and

compared them to those of various other Pseudocolopteryx,

including flaviventris from E.

Argentina. They recorded 20 individuals from Mendoza, Rio Negro, and Neuquén,

all in W. Argentina. They also performed 17 crossed playback experiments. They

confirmed that citreola is a cryptic

species with a different song than that of flaviventris,

and that it deserves status as a biological species separate from flaviventris. Their results show the

following:

1)

Birds from W. Argentina match the

vocalizations of Chilean citreola.

2)

In the breeding season it is found from

Mendoza and Rio Negro south to Neuquén. It is absent from these areas in

winter.

3)

An October record from Salta is of citreola (based on song), but could be

of a southbound migrant.

4)

They noted a recent record during

Austral winter from Bolivia. This record pertained to a singing bird, so could

be assigned to the vocal type of citreola.

5)

The voice of citreola can been described as “tic tic tic tic tic tirik-tirik” or

“tick tick tick tick-tick-tick-you.”

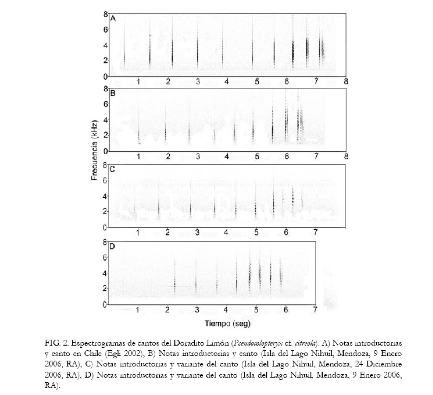

Below are sonograms published in Abalos and Areta (2009), the top is the

Egli recording from Chile, and the three lower ones are from Mendoza,

Argentina.

6)

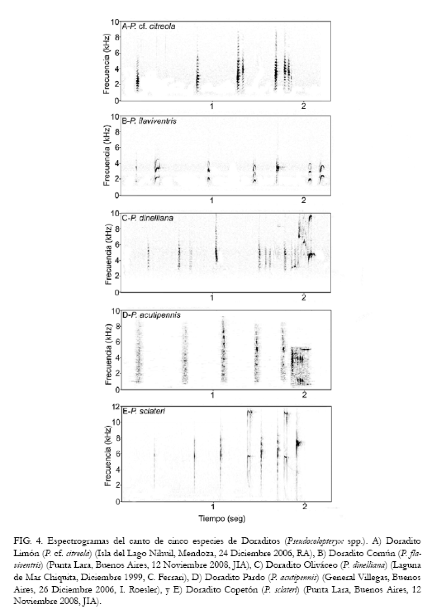

The voice of citreola is distinctive and unlike that of any other Pseudocolopteryx, including flaviventris. Below are published

sonograms in Abalos and Areta (2009) of (from top to bottom) citreola, flaviventris, dinelliana,

acutipennis and sclateri.

Although visually most similar to flaviventris,

citreola’s introductory notes are

very similar to those of dinelliana,

although the important terminal flourish is quite different.

7)

The singing behavior of citreola differs from that of flaviventris, with up-and-down

mechanical head movements in citreola,

although there are both up-and-down and side-to-side rhythmical movements done

by flaviventris.

8)

In playback experiments citreola always ignored songs of flaviventris, whereas they always

strongly responding to songs of citreola.

Similarly flaviventris never

responded to playback of citreola

songs, whereas they strongly responded to flaviventris

songs. Samples were small, but the response was quite clear.

9)

In Argentina the Monte Desert

essentially separates the breeding distribution of citreola in the west and flaviventris

in the east. They have allopatric breeding distributions, at least based on

present data.

Some additional personal notes: I have examined and measured

the type specimen in New York (Landbeck’s specimen), and it is essentially like

flaviventris but a bit longer-winged,

perhaps brighter yellow below. and with a stronger cinnamon tone on the crown.

There is essentially no reliable way to separate citreola and flaviventris

based on specimens other than the longer wing, although doubtless there will be

overlap in a larger series. The real difference is the voice.

Also, in Chile the distribution of this bird is in the

central zone from Santiago south to Valdivia, and it is nowhere common. Its

highest density appears to be near the city of Chillan. All records are from

spring – summer, it appears to leave Chile during the winter.

English Names: There is no English name for citreola. In Abalos and Areta they used the moniker “Doradito

Limón” or Lemon Doradito, based on the scientific name. The Chilean name for

the bird is the imaginative “Pajaro Amarillo” or Yellow Bird. Unfortunately

lemon or yellow are descriptors that fit all Pseudocolopteryx and are therefore not that informative. Given that

a new name is needed, perhaps it is best to base it on the most distinctive

aspect of the bird, its song. In the spirit of many species of Cisticola, I propose this bird’s English

name be “Ticking Doradito.” The song does indeed clearly sound like a series of

tick notes that speed up at the end. This is a better descriptor of the song

than the name of flaviventris, which

hardly warbles. One could also opt for the patronym Landbeck’s Doradito,

although I find this less colorful and also less useful than “Ticking

Doradito.” I realize this name may sound odd, but it is distinctive, short and

unique.

Recommendation: I propose that the name citreola

be dusted off and brought back to life, and it be given to a species level

taxon breeding in Chile and W, Argentina and wintering at least to Bolivia – Pseudocolopteryx citreola, the Ticking

Doradito.

Literature Cited.

Abalos, R. & J. I. Areta. 2009, Historia Natural y

vocalizaciones del doradito limón (Pseudocolopteryx cf. citreola) en Argentina.

Orn. Neotrop. 20: 215–230

Bostwick, K. S., and K. Zyskowski. 2001. Mechanical sounds

and sexual dimorphism in the Crested Doradito (Tyrannidae: Pseudocolopteryx

sclateri). Condor 103:861-865.

Egli, G. 2002. Voces de las aves chilenas. UNORCH, Santiago

de Chile.

Hellmayr, C. E. 1927. Catalogue of

birds of the Americas and the adjacent islands in Field Museum of Natural

History. Initiated by Charles B. Cory, continued by Charles E. Hellmayr. part

5. Tyrannidae

Landbeck, L. 1864. Contribuciones a la Ornitología de Chile.

An. Univ. Chile 24: 336–348.

Wetmore, A. 1926. Observations on the

birds of Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay and Chile. Bull. U.S. Natl. Mus. 133:

1–448.

Alvaro

Jaramillo, March 2010

Comments

from Robbins:

“YES. The

vocal data clearly support recognition of citreola as a species and I

like Alvaro’s English name suggestion.”

Comments

from Bret Whitney:

“Yes. I first recorded this bird on 7 Nov 1986, and

immediately recognized it as very different from P. flaviventris. It showed

no interest in a recording of flaviventris

from Buenos Aires province. Looking into

it, I dug up the name citreola, and

called attention to its validity to numerous ornithologists over the

years. The work has now been done and

its range more clearly defined, so I would definitely vote to recognize citreola at the species level. In my opinion, it is the most endangered

species in the Tyrannidae. Ticking

Doradito sounds fine for an English name though they all “tick” to one degree

or another. Another name to consider

might be Neglected Doradito; hopefully the past tense will become ever more

appropriate and poignant as it receives more attention from this point

forward. Even if it one day becomes the

“protected doradito”, it remains that the big story was that it was neglected

for so long before we stepped up.

doradito desatendido, yeah.”

Comments from Stiles: “YES. All the evidence points to species status for citreola. “Ticking Doradito” seems OK as an English name – I hesitate to go for “Neglected” or something similar because there are probably a fair number of similar cases waiting for attention. This is the sort of analysis we really need to sort out such cases, and “neglect” or no, it was worth waiting for!”

Comments

from Nores:

“YES. Sus voces

diferentes muestran claramente de que se trata de dos especies distintas, a

pesar de su parecido. Especialmente importante considero los experimentos de

playback realizados por Abalos y Areta (2009).”

Comments

from Schulenberg:

“YES to

recognize citreola as a species. I also vote in favor of "Ticking

Doradito" was the English name.”

Comments

from Remsen: “YES. Nice work documenting species rank – all data

are consistent with treatment as a separate species. “Ticking Doradito” is fine with me.”