Proposal (587) to South American Classification Committee

Split Gymnopithys leucaspis into two species

Effect on SACC: This proposal, if passed,

would split Gymnopithys leucaspis

into two species, a trans-Andean G.

bicolor and a cis-Andean G. leucaspis.

Background: Gymnopithys bicolor is a humid lowland forest antbird distributed

both east and west of the Andes. Nine subspecies are currently recognized: five

in Central America and western Colombia/Ecuador (the bicolor group, hereafter bicolor)

and four in the northwest Amazon basin (the leucaspis

group, hereafter leucaspis). The

status quo classification followed by SACC (tagged as “proposal badly needed”)

lumps bicolor and leucaspis following the rationale

outlined by Zimmer (1937a). However, various authors have followed the

alternate treatment of splitting bicolor and

leucaspis as separate species (Willis

1967, Hilty & Brown 1986, Sibley & Monroe 1990). There is now

sufficient data describing patterns of genetic, vocal, and plumage variation

within this complex for SACC to vote on these alternatives.

Genetic data: Hackett (1993) found significant (~5%) allozyme

divergence between trans-Andean bicolor and

Amazonian leucaspis, though refrained

from making a taxonomic recommendation and suggested analyzing these

populations with more sensitive molecular markers. More recently, Brumfield et

al. (2007) included single samples of both leucaspis

and bicolor (as well as single

samples of the other three recognized Gymnopithys

species) in a broader phylogeny of ant-following antbirds. This study used

both mitochondrial (cyt b, ND2, ND3) and nuclear (f5) markers, and found

strong support for a sister relationship between leucaspis and G. rufigula,

a congeneric species with an allopatric Amazonian distribution (G. rufigula is a Guianan Shield species,

leucaspis present in northwest

Amazonia), with trans-Andean bicolor sister

to the combined leucaspis and G. rufigula group (see snapshot of their

tree below).

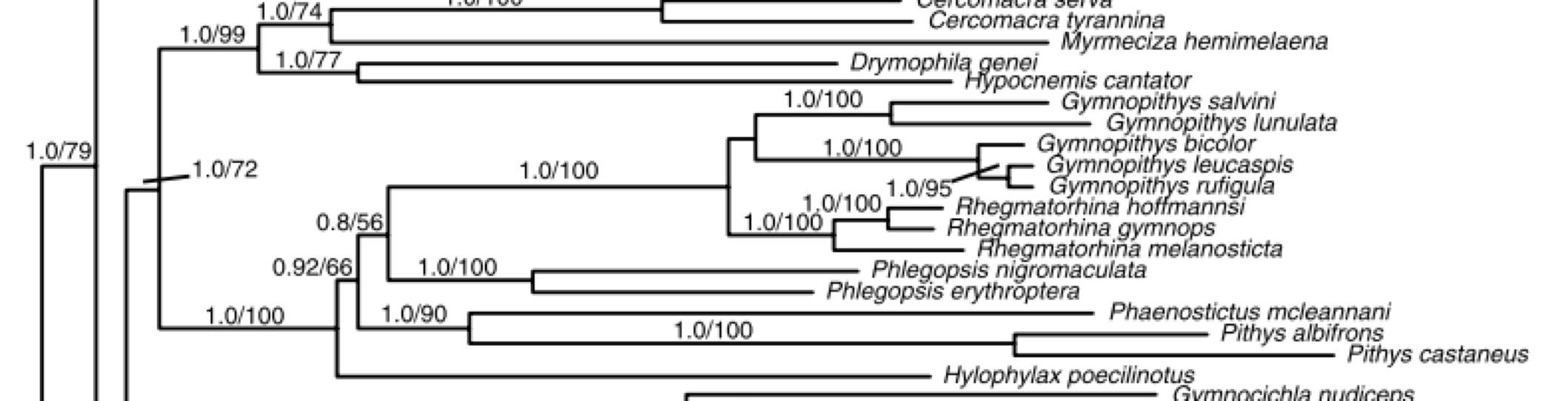

The relevant portion of the maximum-likelihood tree

presented by Brumfield et al (2007). Bayesian (before slash) and bootstrap

(after slash) support values are given. This tree was inferred from the concatenated

data matrix of three mitochondrial and one nuclear gene sequences.

Vocal data:

Statistical differences in antbird vocalizations have been used to justify

splitting of antbird species. However, there is no published analysis of

vocalizations within G. leucaspis (as

currently defined, including bicolor).

The species account in Handbook of Birds of the World (Zimmer and Isler 2003) provides a detailed verbal description of leucaspis and bicolor loudsongs, stating that bicolor

song “starts with long, upslurred whistles that shorten rapidly and gain in

intensity, followed by shorter notes that drop in pitch and intensity before

becoming harsh” while that of leucaspis “begins

with upslurred whistles at an even pitch that shorten into rather abrupt notes

dropping in frequency and intensity, then lengthen and increase again in

intensity, finally decreasing in intensity and becoming harsh.” Additionally,

the loudsong of bicolor is reported

to be ten notes, compared to 20 for leucaspis,

though the HBW account (Zimmer and Isler 2003)

also notes that loudsongs are “quite variable in length”.

Plumage data: For antbirds, plumage is

rather divergent within Gymnopithys: G. rufigula is entirely brown with

patches of cinnamon, and G. salvini and

lunulata are sexually dichromatic,

with gray males and brown females. In contrast, plumage variation in bicolor and leucaspis is relatively slight, with subspecific plumage variation

in head/side coloration and overall darkness. Nevertheless, there appears to be

diagnostic plumage differences between these two groups: the bicolor group has two plumage traits – a

black subocular area and blue-gray plumage behind the eye – that the leucaspis group lacks.

Taxonomic possibilities:

There are two possible treatments at this time.

1. Maintain the status quo, leaving all taxa within both bicolor and leucaspis groups in a broadly defined G. leucaspis.

2. Split

G. bicolor from G. leucaspis.

Recommendation: I suggest that current evidence supports splitting bicolor from leucaspis. The strongest data supporting this split is Brumfield et

al.’s (2007) finding that the Amazonian leucaspis is sister to Amazonian G. rufigula and not trans-Andean bicolor. As the species status of G. rufigula has not been questioned,

these genetic relationships strongly argue bicolor

and leucaspis should be treated

as different species.

Vocal and plumage data supporting this split are less

conclusive. Loudsongs may differ (Zimmer and Isler 2003), but have not yet been

subjected to quantitative analysis or behavioral playback experiments. Plumage

is likewise similar between bicolor and

leucaspis, though there are

diagnostic differences in multiple plumage patches, providing weak support for

the proposed split.

In sum, genetic divergence and the sister relationship of leucaspis with G. rufigula support splitting bicolor

from leucaspis. This split is

weakly supported by vocal and plumage divergence. This proposed treatment is

also consistent with the commonly found pattern of divergence between cis- and

trans-Andean populations of widely distributed lowland forest taxa.

Vernacular

Names:

If passed, this proposal would require new English names for bicolor and leucaspis. Ridgeley and Greenfield (2001) suggested “White-cheeked

Antbird” for leucaspis and retaining

“Bicolored Antbird” for bicolor. This

treatment emphasizes the most prominent plumage difference between the two

taxa, the white “cheek” of leucaspis.

These English names therefore seem appropriate, though the committee could also

consider alternatives.

Literature Cited:

Other papers are cited in

the SACC bibliography

Ben Freeman, September 2013

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Comments

from Stiles: “YES,

although a more comprehensive analysis of vocalizations, including use of

playbacks, would be nice. Because both species are common, vocal birds, surely

enough recordings exist in Cornell and Xenocanto to perform such an analysis.

However, the genetic data seem convincing and the slight but diagnostic plumage

differences seem on a par with several other recent splits in the

Thamnophilidae.”

Comments

from Pacheco: “YES.

O somatório de evidências, sobretudo

o mais recente estudo de Brumfield et al.

(2007), dão suporte apropriado à adoção da proposta aqui apresentada.”

Comments from Zimmer: “YES. I think that the only reason that the

proposed split “is weakly supported by vocal and plumage divergence” is that

there has been no quantitative vocal analysis of the two taxa. I suspect that such an analysis would show

that loudsongs of leucaspis and bicolor differ at least as does either

of them from rufigula. Vocal differentiation between allospecies in

the obligate ant-following genera (particularly within this species-group of Gymnopithys and the entire genus of Rhegmatorhina) appears to be pretty

conservative from an evolutionary standpoint – perhaps there is some conferred

advantage in signal recognition between different species that are all in the

mode of constantly searching for the same moving target (ant swarms), and

having to coexist at swarms while competing for prey. At any rate, the genetic data revealing the

sister relationship between leucaspis

and rufigula pretty much dictates

either splitting off bicolor, or

lumping all three groups (rufigula, leucaspis, bicolor) into one very bizarre (given the striking plumage

differences between rufigula and the

other two) species, something that I don’t think anyone is advocating.”

Comments

from Jaramillo: “YES – leucaspis sister to rufigula I find odd and disconcerting although vocally these three

forms are very similar. Still, the genetic separation between leucaspis and bicolor is strong, and although it would be great to have a more

formal analysis of voice, what is available suggests diagnosable differences in

voice, although slight. But rather than lumping rufigula into this species, I think the option of separating bicolor and leucaspis is the better one.”

Comments

from Robbins: “YES, for

splitting Gymnopithys leucaspis into

two species, as genetic data show that Amazonian leucaspis is more similar to the morphologically distinct G. rufigula than leucaspis is to trans-Andean bicolor.”

Comments

from Pérez-Emán: “A

tentative YES based on Brumfield et al. (2007) data, as the alternative

possibility to lump rufigula, bicolor and leucaspis is not in agreement with plumage differences between rufigula and bicolor/leucaspis.”

Comments

solicited from Mort Isler:

“Although I

have no new vocal analysis to add, I agree with Kevin Zimmer's remarks in his

response to Proposal 587 that it is highly likely that quantitative vocal

analysis of Gymnopithys taxa will

show that ‘loudsongs of leucaspis and

bicolor differ at least as does

either of them from rufigula.’ In

this case, for reasons described in the proposal, it seems reasonable to make

the split without thorough vocal analysis.”

Comments

from Remsen: “YES, with my thoughts exactly as stated by

Jorge.

“As for

English names, there will be those who go ballistic that we don’t come up with

new names for both daughter species. As

much as I appreciate that logic and urge that we do so in most cases, there are

extenuating circumstances. First, in

this case, the two are not sister species – that’s the rationale for the split

– so any sort of compound name is completely out unless rufigula also gets one, which would concoct and create a novel name

for a long-established one. In this

case, “White-cheeked Antbird” has a long history, going back to at least

Ridgely’s (1976) Panama book and used by Sibley & Monroe (1990), so we

already have a good name with a historical track record for leucaspis.”