Proposal

(676) to South American Classification Committee

Split the

Sharp-beaked Ground-Finch (Geospiza

difficilis) and the Large Cactus-Finch (Geospiza

conirostris) into multiple species

Background

Although

work on speciation, hybridization, beak size evolution, and many other topics

have been studied in depth, and sometimes in novel ways in the Darwin’s

Finches, it is only recently that a modern phylogeny was produced for this

group of tanagers (Petren et al. 2005). It also has been clarified that the

Darwin’s Finches are part of the “dome nest clade” which includes Tiaris and various other largely

Caribbean taxa (Burns et al. 2002). However, even in recent molecular

phylogenies, populations from different islands were not sampled, leaving in

question whether morphologically unique populations were in fact also

genetically unique. Further, these molecular phylogenies have been based on

mtDNA and a few microsatellite loci.

New

Information

Lamichhaney

et al. (2015) have produced a new molecular phylogeny, including samples from

multiple islands for various species of Darwin’s Finches. This study is based

on a whole-genome re-sequencing of 120 individuals. They discovered evidence

for widespread historical gene flow between various populations of Darwin’s

Finches, and that genetic diversity is higher than would be expected in small

insular populations, likely through gene flow from other species. Their results

upheld the general phylogenies proposed recently; however, they differed in

finding that various populations of Geospiza

difficilis (Sharp-beaked Ground-Finch) and Geospiza conirostris (Large Cactus-Finch) are not sisters to each

other. They also discovered a locus associated with beak shape, and discussed

this in terms of ecology and evolution of members of this group. They concluded

that the group is approximately 1 million years old, and that certain branches,

such as the tree finches are rather recent (200,000 years).

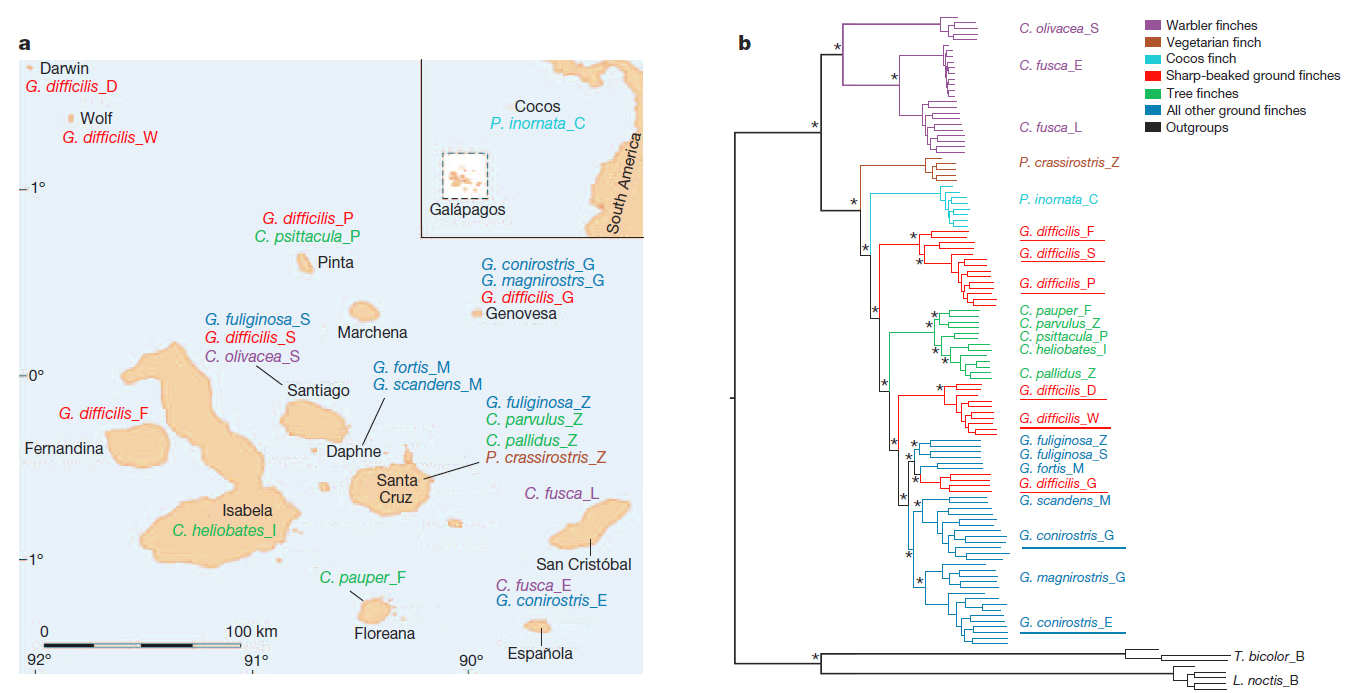

Below

is the suggested phylogeny as well as a map of populations sampled.

[Note

from Remsen: In the tree, difficilis

G[enovesa]= acutirostris;

difficilis F, S, P = nominate difficilis; difficilis D[arwin], W[olf] = septenttionalis; G.

conirostris G[enovesa] = propinqua; G. conirostris

E[spañola] = nominate conirostris.

Evidence for species splits

1) Geospiza difficilis,

Sharp-beaked Ground-Finch. Results confirm that there are three taxa widely

separated in the phylogeny. Three species level taxa are recommended to be

recognize:

G. acutirostris Ridgway; found on

Genovesa.

G. difficilis Sharpe; found on Pinta,

Fernandina, and Santiago.

G.

septentrionalis Rothschild and Hartert; found on Wolf and

Darwin.

These were formerly recognized as species,

based on differences in size and bill shape. The species difficilis has a straight culmen and is truly sharp beaked, whereas

septentrionalis has a curved culmen.

These populations also differ in song (Grant et al. 2000). The species acutirostris is very much smaller in

mass than the other two; in many ways it resembles a Small Ground-Finch (G. fuliginosa), and in fact it is

genetically much closer to fuliginosa

and fortis (Medium Ground-Finch) than

it is to true Sharp-beaked Ground-Finch. Curiously song is more similar to septentrionalis (Grant et al. 2000).

Lamichhaney et al. (20150 suggested that acutirostris

may be a species derived from mixed ancestry, i.e. of hybrid origin, but that

it is a distinct and separate entity (species).

2) Geospiza conirostris Large

Cactus-Finch. The two populations, one on Genovesa and one on Española, are

each genetically more similar to other species than they are to each other. The

Genovesa population (propinqua) is

sister to the Common Cactus-Finch (G.

scandens), whereas the nominate forma is sister to the Large Ground-Finch (G. magnirostris). This mirrors

morphology, both are big and large-billed, but propinqua has a long bill like a Cactus-Finch, whereas conirostris has a deep bill like a Large

Ground-Finch. The two forms of conirostris

differ in song, and song playbacks on Genovesa found only a weak attraction

effect when playing back songs from Española (Ratcliffe et al. 1985). Note that

there was absolutely no response from playback of Large Ground-Finch songs on conirostris. The playback results

between propinqua and Common

Cactus-Finch are more complex. The form propinqua

reacts strongly to one song type of Common Cactus-Finch from Daphne Major, but

Common Cactus-Finch does not react to songs of propinqua. Furthermore male Common Cactus-Finch discriminated

strongly against propinqua when

tested with a pair of museum specimen models in female plumage, one of propinqua and one of local scandens (Common Cactus): the reciprocal

experiment on Genovesa was not completed (Ratcliffe et al. 1983). Putting this

together, the evidence suggests that Common Cactus-Finch and propinqua, its sister species, would

rarely if ever interbreed if they came into contact. Note that there are old

records of Large Cactus-Finch from Darwin and Wolf islands. However, these are

based on only a few records and specimens. The current status of a population

on Darwin Island is unclear, and there are none currently on Wolf Island. The

subspecies darwini has been named,

although there is no evidence that there is a recent population from Darwin

Is., and in fact there has been confusion as it is thought that these may have

been stray Large Ground-Finches (Wiedenfeld 2006).

Recommendation

I

recommend a Yes vote to separate these species, raising the number of Darwin’s

Finch species from 15 to 18. Note that geographically the existence of a Large

Cactus-Finch on Darwin and Wolf islands is very unlikely, unless it also was a

separate and unique population. There is no recent evidence of a long-term

sustaining population on Wolf. It is unclear if the species is present and

common on Darwin Island, and indeed these may have been either stray Large

Ground-Finch, or perhaps a population of Large Cactus-Finch. Therefore, I think

it is best to delay any decision on what to do with darwini (if indeed it still exists), until genetic data from

specimens is studied. In the past darwini

has been lumped with propinqua.

English

Names

G.

acutirostris Ridgway;

found on Genovesa. – Restricted to Genovesa, why not Genovesa Ground-Finch? It is small and similar to Small

Ground-Finch, so a size or even a bill shape name does not jump out based on

its morphology.

G.

difficilis Sharpe;

found on Pinta, Fernandina and Santiago. – This is the most widespread, and

perhaps the archetype “Sharp-beaked Ground-Finch” so I would suggest letting it

retain the name Sharp-beaked

Ground-Finch.

G. septentrionalis Rothschild

and Hartert; found on Wolf and Darwin. Vampire

Ground-Finch, based on its well-known habit of feeding on booby blood. The

colloquial Vampire Finch has been in use for some time, but to be consistent I

think we would need to use Ground-Finch.

G.

conirostris; found on Española. This huge-billed bird is

most similar to the Large Ground-Finch, which it is sister to. I don’t know if

one can come up with a morphological based name, such as Thick-billed

Ground-Finch that mentions anything unique? Perhaps Española Ground-Finch would be the best name, because it is endemic

to that island.

G.

propinqua; found on Genovesa. This is sister to the Common

Cactus-Finch, so perhaps it should keep the name Large Cactus-Finch? Although this may be confusing as it is not any

more widespread or easily found than conirostris.

Genovesa Cactus-Finch would be

another possible name, noting that above we already have a Genovesa

Ground-Finch.

VOTING:

Subproposal

A – Accept separation of G. difficilis

into three species.

Subproposal

B – Accept separation of G. conirostris

into two species.

If

these above proposals pass, then we will consider proposals on English Names.

Literature

Cited

Burns, K. J., S.J.

Hackett and N. K. Klein. (2002). Phylogenetic relationships and morphological

diversity in Darwin’s Finches and their relatives. Evolution 56(6): 1240–1252

Grant, B. R., Grant, P.

R. & Petren, K. (2000). The allopatric phase of speciation: the sharp

beaked ground finch (Geospiza difficilis)

on the Galapagos islands. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 69, 287–317.

Lamichhaney, S., J.

Berglund, M. Sällman Almén, M. Khurram, M. Grabherr, A. Martinez-Barrio, M.

Promerová, C.-J. Rubin, C. Wang, N. Zamani, B. R. Grant, P. R. Grant, M. T.

Webster and L. Andersson (2015). Evolution of Darwin’s finches and their beaks

revealed by genome sequencing. Nature 518: 371–375.

Petren, K., P.R. Grant,

B. R. Grant and L. F. Keller (2005). Comparative landscape genetics and the

adaptive radiation of Darwin’s finches: the role of peripheral isolation. Molecular

Ecology 14: 2943–2957

Ratcliffe, L. M. &

Grant, P. R. (1983). Species recognition in Darwin’s finches (Geospiza, Gould). II. Geographic

variation in mate preference. Anim. Behav. 31, 1154-1165.

Ratcliffe, L. M. &

Grant, P. R. (1985). Species recognition in Darwin’s finches (Geospiza, Gould). III. Male responses to

playback of different song types, dialects and heterospecific songs. Anim.

Behav. 31, 290-307.

Wiedenfeld, D. A.

(2006). Aves, The Galapagos Islands, Ecuador. Check List 2(2): 1-27.

Alvaro

Jaramillo, July 2015

=========================================================

Comments

from Zimmer: “YES to

Subproposal A and YES to Subproposal B, for reasons detailed by Alvaro in the

Proposal.”

Comments from Stiles:

“A)

YES. No problem here.

“B) YES, given

the more complete genetic sampling (all this makes me wonder about splitting up

the small, compact clade of Camarhynchus (?)

in green into all those species; presumably vocal evidence).”

Comments

from Pacheco: “YES to A

and YES to B. I am backing Alvaro’s two recommendations from molecular

phylogeny with samples geographically well distributed.”

Comments from Robbins: “NO. Having read the McKay and Zink (2015) paper

on Geospiza, in which they suggest

there is only a single species, one needs to pause and rethink things. So, we want to add yet more species to a

highly controversial Geospiza species

limits definition? For now, I vote no,

if for no other reason than to bring to the attention that the committee needs

to be aware of the latest perspective on this group.”

Additional comments from Robbins:

“With regard to the Geospiza proposal. The abstract of the Lamichhaney et al. (2015)

paper states the following:

‘Phylogenetic

analysis reveals important discrepancies with the phenotype-based taxonomy. We

find extensive evidence for interspecific gene flow throughout the radiation.

Hybridization has given rise to species of mixed ancestry.’

“Additionally, in the text on

the first page, ‘Extensive

sharing of genetic variation among populations was evident, particularly among

ground and tree finches, with almost no fixed differences between species in

each group (Extended Data Fig. 2).’ Finally, note that sampling is

certainly not extensive, so hybridization may well be underrepresented.

All of this should cause one to pause and think about the McKay and Zink

perspective. As we have appreciated throughout our careers, this a very

complex situation and it would be an understatement to say attempting to apply

traditional species limit views is difficult.

“I certainly would welcome

input from those who have a deep understanding of the genetics and analyses of

the Lamichhaney et al. (2015) results.”

Comments

from Remsen: “YES to A and B. Darwin’s finches continue to yield insights

into the complexity of the early stages of speciation. These populations have all diverged to the

point in terms of voice and behavior consistent with their treatment as BSC

species. In my view, that their mtDNA

has not yet sorted out reflects the lag time between these neutral loci versus

those under selection, or a degree of ongoing hybridization that does not

conflict with species rank (as in all hybridizing taxa that are also treated as

species under BSC).”

Comments

from Cadena: “YES.

The genomic data clearly point to problems with species delimitation, and

Alvaro has nicely summarized evidence showing the genomic data match well with

geography, morphology, vocalizations, and behavior. The paper mentioned by Mark

is indeed intriguing, but I did not find the analyses of morphological data in

that study entirely satisfying. In fact, with Felipe Zapata and Iván Jiménez,

we are working on re-analyses of morphological data using quantitative

approaches, and the results we get do not quite agree with the conclusions of

McKay and Zink based on their PCAs. We hope to write up a note describing this

soon.”