Proposal

(752) to South American Classification Committee

Split Sclerurus mexicanus into multiple

species

The following proposal is a set of

hierarchical taxonomic schemes for the Sclerurus

mexicanus complex. It expands upon Proposal 603 with newly published vocal

analyses (Cooper & Cuervo 2017). This proposal is meant to be considered

sequentially (i.e., Part I must be approved to consider Part II).

Part I

Split Sclerurus mexicanus into two species: Sclerurus mexicanus and Sclerurus obscurior.

Effect on SACC: Sclerurus mexicanus would be split into two species that are

assumed to be parapatric in the Darién Gap. All known South American

populations would become S. obscurior;

S. mexicanus would be moved to the

hypothetical list.

Background: The genus Sclerurus currently contains six widespread, polytypic species. Sclerurus mexicanus has the broadest

distribution of any Sclerurus, with

seven subspecies occurring from northern Mexico to southern Brazil (Cooper and

Barragan 2017; Fig. 1). Despite the recognized diversity and broad distribution,

differences are minimal (Remsen 2003), and subspecies distributions are still

incompletely known (Cooper and Barragan 2016; Cooper and Cuervo 2017). d’Horta

et al. (2013) found that Sclerurus

mexicanus is not monophyletic as currently defined. Rather, three major

clades were discovered that form a polytomy in the rufous-throated leaftosser

clade: (1) S. mexicanus (subspecies mexicanus and pullus) in North America; (2) S.

rufigularis; and (3) S. mexicanus

(subspecies obscurior, andinus, macconnelli, and peruvianus)

in South America. Similarly, recent vocal analyses only found S. rufigularis to be statistically

diagnosable when analyses allowed for multiple species within the S. mexicanus complex (Cooper and Cuervo

2017).

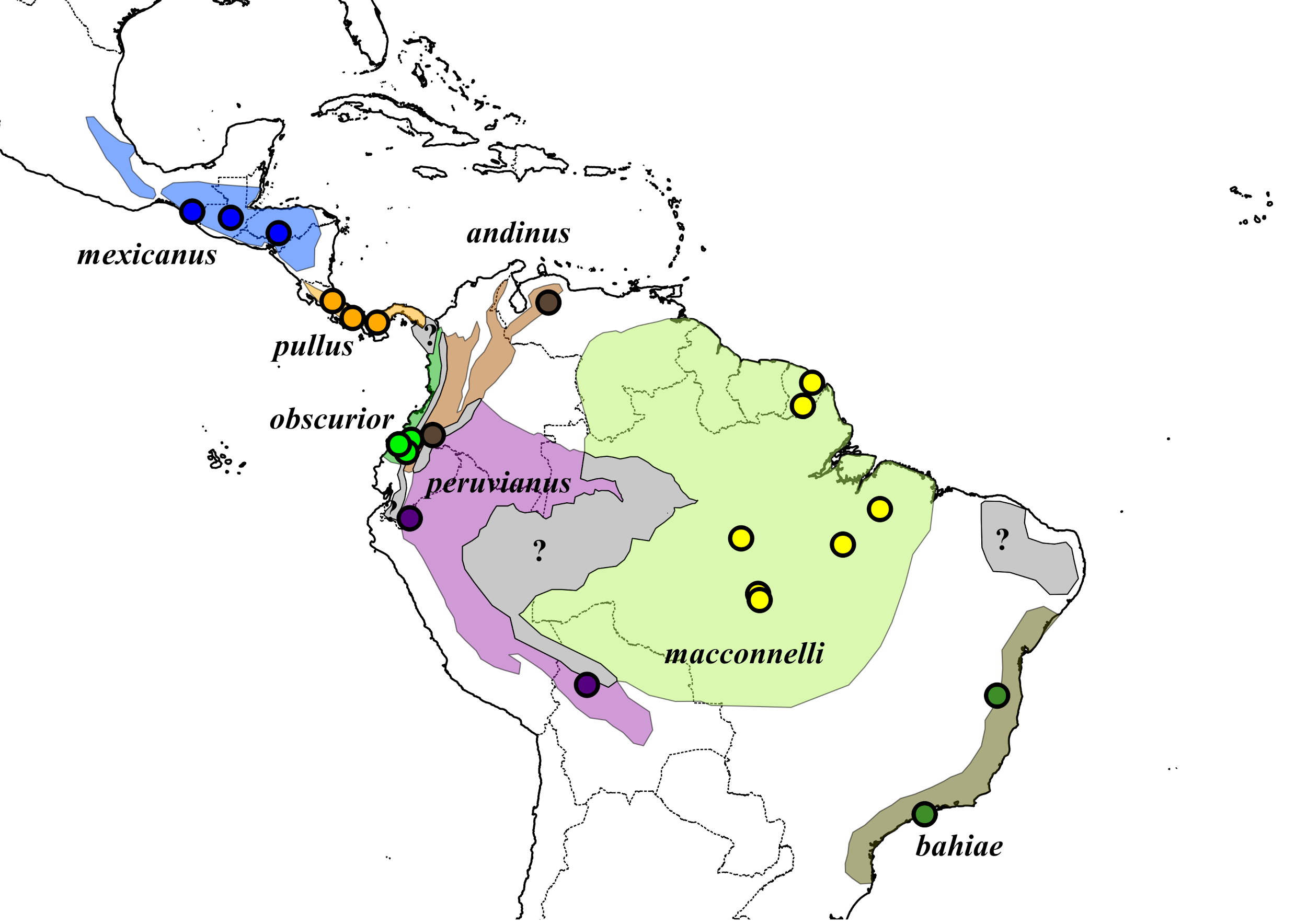

Figure 1. A map of

subspecific distributions within Sclerurus

mexicanus. Points represent localities from which vocalizations were

sampled. Figure from Cooper and Cuervo (2017).

Within the S.

mexicanus group, North and South American populations appear wholly

allopatric, diagnosably monophyletic (d’Horta et al. 2013), and vocally

distinct (Cooper and Cuervo 2017). Unless all rufous-throated leaftossers are

considered a single species (including S.

rufigularis), the most prudent decision is to split S. mexicanus into two taxa with no known geographic overlap:

1.

Sclerurus mexicanus (Sclater 1856). Suggested English name:

Central American Leaftosser. Type locality: Cordoba, Veracruz, Mexico. This

species contains two subspecies: mexicanus

(from northern Nicaragua north to east Mexico) and pullus (from northern Costa Rica south to southern Panama). This

includes certus (Chubb 1919, from

Guatemala), which is considered a synonym of mexicanus (Hellmayr 1925).

2.

Sclerurus obscurior (Hartert 1901). Suggested English name: Dusky

Leaftosser. Type locality: Lita, Esmeralda, Ecuador (ca. 600m). This species

contains five subspecies: obscurior

(the Choco lowlands), andinus (the

mid-montane Andes of Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela), peruvianus (the eastern foothills of the Andes and western Amazonia

in Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, and probably Brazil), macconnelli (eastern Amazonia and the Guianan shield), and bahiae (the Atlantic Forest of Brazil).

Thus, if accepted, all confirmed populations

in South America would become subspecies of S.

obscurior.

Part IIA

Split Sclerurus mexicanus into Sclerurus mexicanus and Sclerurus pullus. Advisory only to NACC

Effect on SACC: This would only become

important if the population pullus is

confirmed in Northern Colombia. Sclerurus

pullus is known from adjacent eastern Panama. This would have no effect on

the main SACC list at the present time; S.

mexicanus would be removed from the hypothetical list and replaced with S. pullus.

Background: Sclerurus mexicanus and Sclerurus

obscurior have no known regions of overlap, with no confirmed records of Sclerurus mexicanus (sensu Part I) in

the SACC region. However, given that S.

mexicanus pullus occurs in eastern Panama immediately adjacent to Colombia,

it is possible that the taxon will be found in the SACC area in the future.

Despite limited vocal data, differences were recovered between S. m. mexicanus and S. m. pullus (Cooper and Cuervo 2017) and populations are

reciprocally monophyletic (d’Horta et al. 2013). A split of these two taxa is

therefore warranted. This will have no effect at the present time on the SACC

list, but will change any future records of S.

mexicanus from northern Colombia to S.

pullus, as follows:

Sclerurus pullus (Bangs 1902).

Suggested English name: Isthmian Leaftosser (thus altering S. mexicanus to Tawny-throated or Mexican Leaftosser). Type

locality: Boquete, Panama. Distributed from northern Costa Rica through the

Darién in Eastern Panama. This species may occur in the Darién and Urabá

regions of Colombia, and may exist parapatrically with S. obscurior. This species includes the synonym anomalus (Bangs and Barbour 1922), which

has erroneously been synonymized with andinus

in the past (Peters 1951).

Part IIB

Split Sclerurus

obscurior into three species: Sclerurus

obscurior, Sclerurus andinus, and

Sclerurus macconnelli.

Effect on SACC: Sclerurus obscurior would become three allopatric species, with Sclerurus obscurior being retained by

lowland Choco populations. Andean populations would become Sclerurus andinus, and Amazonian/Atlantic Forest populations would

become Sclerurus macconnelli.

Background: d’Horta et al. (2013) recovered

multiple monophyletic clades within South American S. obscurior (sensu Part I). These groups correspond to all

subspecies for which genetic data were available (i.e. all subspecies except bahiae), with the shortest branch lengths

for the division between S. o. peruvianus

and S. o. macconnelli (Fig. 2).

Given this short branch length, it is reasonable to consider S. peruvianus and S. macconnelli conspecific (but see Part III below). Cooper and

Cuervo (2017) tested multiple different partitioning schemes on Sclerurus songs and found the highest

support for a similarly conservative partitioning scheme that splits obscurior and andinus but retains peruvianus,

macconnelli, and bahiae as a single polytypic species.

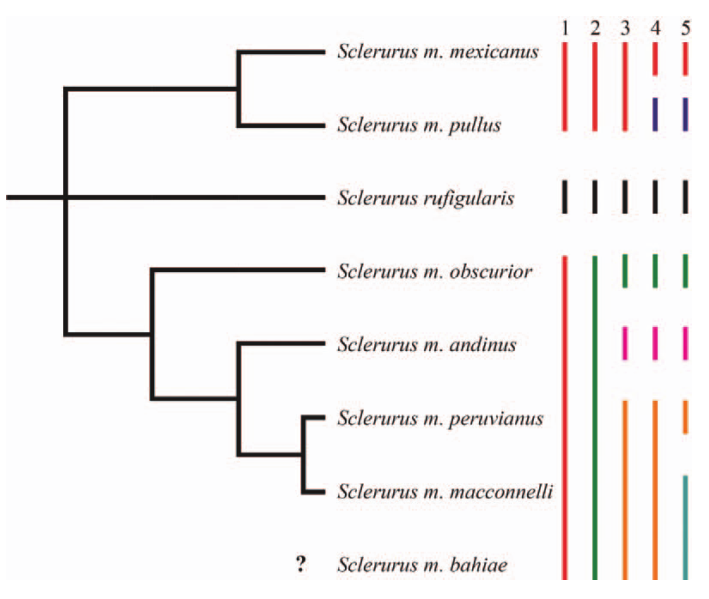

Figure 2. Species partitioning schemes tested

for the S. mexicanus complex. Branch

lengths are not to scale, but are presented proportionally and the tree depicts

monophyletic assemblages recovered by d’Horta et al. (2013). Colored lines,

labeled 1-5, represent groupings discussed in Cooper & Cuervo (2017); with

respect to this proposal, partition 2 corresponds to Part I, partition 4 to

Part II, and partition 5 to Part III. Figure from Cooper and Cuervo (2017).

Genetic data supports the split of andinus from obscurior (d’Horta et al 2013): “Along the continuum of humid

forests from the Chocó lowlands to the slopes of the western Andes, two

lineages appear segregated elevationally: S.

obscurior, and S. andinus found

locally from about 1000 m (often up to 2000 m). The two lineages are

potentially syntopic at an intermediate point of the elevational and ecological

gradient, where no obvious physical barrier is in place… the lowland Chocó

(i.e. S. obscurior) and the Andean

foothill species (i.e. S. andinus)…[last]

shared a common ancestor in the Early Pliocene, between 3.6 and 6.0 Ma”.

Based on these data, Part IIB therefore

proposes elevation of S. andinus and S. macconnelli to species level. S. obscurior would then become a

monotypic taxon restricted to the Choco (with the suggested English name ‘Dusky

Leaftosser’). The descriptions for these new taxa would be as follows:

1.

Sclerurus andinus (Chapman 1914). Suggested English name:

Andean Leaftosser. Type locality: Buenavista, above Villavicencio, Colombia, on

the E slope of the Eastern Andes (ca. 1370 m). This subspecies resides in humid

submontane forest in western Venezuela (the main Andes and the Sierra de

Perijá), all three Andean ranges of Colombia, and in Western Ecuador. Records

from northeastern Ecuador and southwestern Ecuador (El Oro) may refer to this

taxon.

2.

Sclerurus macconnelli (Chubb 1919). Suggested English name:

Long-billed Leaftosser (as opposed to Short-billed Leaftosser S. rufigularis with which this species

is sympatric; MacConnell’s, Amazonian, or Guianan Leaftosser [as in Cory &

Hellmayr] are also possible English names). Type locality: Ituribisci River,

Guyana. This species would consist of three subspecies: peruvianus of the eastern foothills of the Andes and western

Amazonia; macconnelli of central and

eastern Amazonia and the Guianan shield; and bahiae of the Atlantic Forest of Brazil. Records from Ceará,

halfway between the distributions of macconnelli

and bahiae, are best left

unidentified at this time. While parapatry is assumed between peruvianus and macconnelli, the contact zone is not well known.

Part III

Split Sclerurus

macconnelli into two species: Sclerurus

macconnelli and Sclerurus peruvianus.

Effect on SACC: Amazonian populations of S. macconnelli would be split into two

species, with peruvianus occupying

the western basin and Andean foothills and macconnelli

occupying the lower basin, the Guianan shield, and the Atlantic Forest.

Background: While defined vocal differences

between S. macconnelli subspecies

(sensu Part IIB) were not recovered (Cooper & Cuervo 2017), d’Horta et al.

(2013) recovered two monophyletic groups aligning to the described populations

of peruvianus and macconnelli. Per d’Horta et al. (2013):

“... S. macconnelli and S. peruvianus … are in close

geographical proximity in southern Peru and Bolivia but seem to occupy

different elevations along the cis-Andean foothills”. The magnitude of the

differentiation between macconnelli

and peruvianus is less than any other

branching event within S. mexicanus

sensu lato, including the relationship between S. mexicanus and S. pullus.

Regrettably, no genetic data is presently

available for bahiae, and its

relationship to the rest of the S.

macconnelli complex is uncertain. Thus, Part III opts for the elevation of S. peruvianus to species level while

retaining bahiae as a subspecies of

the geographically proximate S.

macconnelli.

S. peruvianus (Chubb 1919).

Suggested English name: Peruvian Leaftosser (as in Cory & Hellmayr). Type

locality: Yurimaguas, Loreto, Peru. This species replaces macconnelli in northwestern Amazonia and in the higher elevations

of the Andean foothills in southern Peru and Bolivia. Exact range limits are

unknown, but it is known to occur on both sides of the Napo/Amazon Rivers in

Ecuador and Colombia.

Recommendation

Given the amount of genetic and vocal data

available, we recommend the acceptance of Part I and Part II (both A and B).

Five species are repeatedly delimited using both vocal and genetic data, and

best represent the diversity within S.

mexicanus sensu lato. These decisions would remove S. mexicanus from the SACC list and replace it with three species: S. obscurior, S. andinus, and S.

macconnelli. One additional species should be considered hypothetical

within the SACC area (S. pullus)

pending further surveys of the Darién Gap.

Given the present data, we recommend holding

off on Part III. The relationship of bahiae

to peruvianus and macconnelli is not resolved, and there is

no reliable way to identify these taxa in the field at the present time short

of collecting vouchers or genetic samples.

Literature cited

Cooper, J. C. & A.

M. Cuervo. 2017. Vocal variation and species limits in the Sclerurus mexicanus complex. The

Wilson Journal of Ornithology 129:13-24.

Cooper, J. C. &

Barragán, D. 2017. Tawny-throated Leaftosser Sclerurus mexicanus. Neotropical Birds Online

<http://neotropical.birds.cornell.edu/>.

d’Horta, F. M., A. M.

Cuervo, C. C. Ribas, R. T. Brumfield & C. Y. Miyaki. 2013. Phylogeny and

comparative phylogeography of Sclerurus (Aves:

Furnariidae) reveal constant and cryptic diversification in an old radiation of

rain forest understory specialists. Journal

of Biogeography 40:37-49.

Other references in SACC bibliography.

Jacob C. Cooper & Andres M. Cuervo, May 2017

========================================================

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“Part I – YES, data look solid to me, and include multiple independent sets of

data. Note that Central American Leaftosser does not work for me.

“Part

IIA – YES, assuming it eventually is found in Colombia.

“Part

IIB – YES, I find it powerful that obscurior

and andinus are syntopic, and replace

each other elevationally. It is unfortunate that bahiae was not sampled molecularly, as it may shift the tree

perhaps?

Part

III – NO, unresolved as noted in the proposal. Data needed for bahiae, as well as no reliable way to

identify taxa in field!”

Comments

from Stiles:

"YES to part 1. YES to part 2. The split between mexicanus and pullus is deep, suggesting isolation across the Nicaraguan gap in

mountain habitats. YES to part 3,

given the genetic and vocal data and the likelihood of parapatry (or even

sympatry?) at intermediate elevations. NO

to part 4: data are not sufficient for this split at this time."

Comments

from Claramunt:

" NO. Quoting Cooper & Cuervo (2017:13): “…revising

species limits in the group is complicated by subtle phenotypic variation

between lineages and an incomplete understanding of the limits of their distribution.” I fully agree

and this exactly what is missing in this proposal: a better understanding of

phenotypic geographic variation. We know that there is important geographic

variation in plumage (Remsen 2003), mitochondrial DNA (d’Horta et al. 2013),

and vocalizations (Cooper & Cuervo 2017). What we don’t know yet is whether

that variation is just geographic variation in a widespread species or

indicative of multiple species. In particular, a strong match between genetic

and phenotypic subdivisions would suggest reproductive isolation in

differentiated lineages, thus species status. What we observe here is a general

correlation between the different sets of data, but I don’t see evidence of a

strong match across traits.

"For example, affinities of the birds from E Panama are

uncertain; plumage suggests affinities with the South American clade: birds

there have been referred to obscurior and andinus (Wetmore1972,

Remsen 2003). On the other hand, the bird included in d’Horta et al. from E

Panama carried a Central American haplotype (it is identified as pullus in

the paper, but I don’t know if that was based on plumage or a posteriori,

based on DNA). Songs from this region were not analyzed by Cooper & Cuervo

(2017), but a song from this region in xeno-canto sounds to me like a perfect

intermediate between those of Central America and NW South America. So, right

now, we don’t know if this pattern reflects primary intergradation of traits, a

hybrid zone, or sympatry of two isolated lineages.

"Similarly, birds from the Pantepui region have been assigned

to andinus but carry a macconnelli mtDNA, and birds from W

Brazilian Amazonia have been referred to peruvianus but carry macconnelli

mtDNA. Thus, it seems that there are broad mismatches between mitochondrial and

plumage variation, thus suggesting that we are seeing the vagaries of

polymorphic traits within a large and geographically structured population,

rather than discrete lineages evolving independently. A detailed analysis of

plumage variation would be very informative.

"Song variation is also complex and, aside from a general

large-scale correspondence, I don’t see evidence that it matches either plumage

or mtDNA, and the statistical design used by Cooper & Cuervo is problematic

in several respects. First, they did not analyze songs from both sides of

putative contact zones, like Darién Chocó (pullus-obscurior), the W

foothills of the W Andes (obscurior-andinus, all songs of andinus

are from the E slopes of E cordilleras) or Amazonian Andes forelands (peruvianus-macconnelli).

Therefore, the possibility of finding intermediate songs and mismatches was

minimized. Second, univariate pairwise comparisons of song traits was

problematic for two reasons: 1) differences in group means do not prove that

groups are discrete units (cannot distinguish clines from discrete variation),

and 2) incurred in a serious problem of multiple testing (Appendix 2 contains

196 P-values; standard methods for adjusting P-values for multiple test result

in none of the pairwise tests being statistically significant! Note that none

of the P-values are particularly low). Therefore, no statistical evidence

there. The discriminant analysis does provide some support for one of the

proposed taxonomies, but again, the lack of samples near putative contact zones

may have biased the analysis towards good levels of discrimination. Finally,

from the perspective of the biological species concept, there is no information

regarding the potential effect of the geographic variation in song on

reproductive isolation. Actually, birds seem to respond to songs from distantly

related subspecies and they can sometimes switch to a song that is more similar

to that of other subspecies (Cooper & Cuervo 2017:16); this kind of

information is usually taken as evidence of conspecificity under the biological

species concept.

"Finally, the phylogeny of d’Horta et al. (2013) raises the

possibility that mexicanus is not monophyletic, but the evidence is weak

(no statistical support either way). In sum, I can’t find the evidence for the

existence of multiple species within mexicanus."

Comments from Zimmer:

“YES. I think that the genetic and vocal

differences of all Central American populations north and west from the

highlands of western Panama from those of South America provide strong evidence

for at least a two-way split in this complex.

Part IIA. Split Sclerurus mexicanus into S. mexicanus and S. pullus. YES

(tentatively). Again, I think that the

genetic differences are persuasive, and a split here would fit an established

biogeographic pattern of differentiation across the inter-montane gap between

Nicaragua and the Talamanca-Chiriqui highlands.

However, my YES vote comes with the caveat that the situation in the

Darién of eastern Panama really muddles the overall picture. The Proposal treats the birds of eastern

Panama as being referable to S. [m.]

pullus, but other authors (e.g. Remsen in HBW Volume 8) have characterized

the situation in eastern Panama as being one of elevational parapatry, with andinus inhabiting the lowlands, and obscurior replacing it in the

highlands. Looking at this from the

perspective of biogeography, the typical pattern of taxon-replacement that we

see in eastern Panama, is for Talamanca-Chiriqui highland birds to drop out in

the isolated mountains of central Panama (e.g. Coclé-Panama provincial border

region), and for lowland birds to extend eastward at least to the Bayano River

valley before being replaced in the lowlands of Darién by taxa typical of the

Chocó region of Colombia and northwestern Ecuador, with taxa occupying the

Darién highlands either unique to that region, or, showing affinities to Andean

taxa in Colombia. To me, the obvious

break in vocal characters among all “Tawny-throated Leaftossers” is between

Central American birds (verifiable east/south to the highlands of western

Panama) and South American birds east of the Andes. It doesn’t make much sense to me that the

leaftossers from eastern Panama would be referable to pullus. The scenario that

Van proposed in HBW (andinus in the

lowlands and obscurior in the

highlands) for eastern Panama makes more sense to me, and if accurate, the

apparent elevational parapatry and pattern of taxon replacement would argue for

splitting andinus and obscurior from one another, a split that

would probably be supported by plumage differences. I am not familiar with the voices of the

eastern Panamanian mexicanus, and it

doesn’t appear that Cooper & Cuervo (2017) included vocal samples from the

region in their vocal analysis, so I have no confidence that the distributional

boundaries of pullus, andinus and obscurior are being accurately

portrayed. Because of this, and taking

into consideration Santiago’s well-reasoned arguments regarding the lack of

clarity as regards phenotypic variation and congruence of the different data

sets, I’m not willing to go further in splitting up this complex until we know

more. I would echo Santiago’s calls for

better vocal sampling and analysis from both sides of putative contact

zones. So, for now at least, I’m a NO on

Part IIB, and Part III of this proposal.”

Comments

from Pacheco:

“NO. As stressed by Santiago and Kevin, I consider for the moment that data

(vocal, genetic) of some populations are still unavailable so that they can

have a more robust understanding of the specific limits in this complex.

“There

is no assurance that the birds of eastern Panama are "pullus". There is no definition about the affiliation of the

populations of the Pantepui (despite being the type-locality of macconnelli) and the Atlantic Forest. My opinion is that the geographic coverage and

the number of song samples is not enough to guarantee the proposed taxonomic

suggestions. More importantly, vocal analysis did not find perfect congruence

with genetics. Tentatively, I vote YES only for Part I.”

Comments

from Remsen:

“YES to all proposed splits. Although I

strongly appreciated the well-reasoned conservative comments of Santiago and

others, I am strongly influenced by handling specimens of all these taxa and by

the likely elevational separation of taxa that for me is a nail-in-coffin piece

of evidence for species rank. The

differences among S. mexicanus

populations sensu lato are greater

than those between Amazonian populations of S.

mexicanus and S. rufigularis. Continued maintenance of all of these taxa as

a single species masks a lot of what I would consider species-level

biodiversity. Philosophically, in this

group repairing and refining problems in species limits of all taxa recommended

as splits in the proposal (as in taxon rank of bahiae) are secondary concerns compared to maintenance of broad mexicanus.”

Comments

from Robbins:

“Clearly Part 1 is straightforward, thus a "YES",

for splitting Sclerurus mexicanus

into at least two species, S. mexicanus

and S. obscurior.

Part IIA. Given this is outside of our region, I presume we are

not voting on this. Nonetheless, genetic data clearly show there is a deep

split between mexicanus and pullus (as compared to other taxa in

this group), so despite similarity in plumage and vocalizations pullus should be recognized at species

level.

I believe d' Horta et al. (2013) and Cooper and Cuervo have

provided good rationale for recognizing obscurior,

andinus, and macconnelli as species, so a " YES " to Part IIB.

Following Cooper and Cuervo's recommendation, at least for now, I

vote "NO" for part III.

Comments

from Stotz:

“I. YES. This seems

straightforward to me with several datasets showing corresponding separation

between these taxa.

“IIA. I am inclined to

say YES on this split, but it is not a case we actually have to consider given

the currently known distribution of the taxa.

However, the North American committee should probably consider this

issue, especially given that it appears SACC will at very least split obscurior

from mexicanus.

“IIB.

YES.

“III.

NO I can see no reason not to follow the recommendation of the

authors of the proposal based on our current knowledge of the situation.