Proposal (989) to South

American Classification Committee

Treat Ocreatus underwoodii

as multiple species

Background: In an effort to align

world lists, WGAC has split the Ocreatus racket-tails into three

species, a move followed by Clements’/eBird and IOC lists. The main reasons for

this move are based on information provided by Schuchmann et al. (2016);

plumages, morphometrics, display behavior, and biogeography. SACC has not yet

addressed the issue and footnote 62a in Trochilidae says the following:

The

two southern subspecies, annae and addae, were formerly (e.g., Cory 1918) each considered a separate species from Ocreatus

underwoodii, but they were all treated as conspecific

by Peters (1945). Ridgely & Greenfield (2001) suggested that addae

might deserve recognition as a separate species. The subspecies peruana

was also formerly (e.g., Cory 1918) considered a

separate species from O. underwoodii,

but they were treated as conspecific by Peters (1945); Cory (1918) used "cissiurus"

for the species name, but not only does peruana have priority but Peters (1945) considered "cissiurus (= cissiura)"

a synonym of peruana. Schuchmann

et al. (2016) provided evidence from plumage and behavior that Ocreatus

underwoodii should be treated as

four species, with the subspecies addae, annae, and peruana

elevated to species rank. SACC proposal needed.

According

to Schuchmann et al. (2016), Ocreatus comprises between two and four

Biological Species. The plumage characters that they deemed important were: 1)

male ventral coloration, 2) female ventral coloration, 3) tibial tuft (“boot”)

coloration, 4) undertail coloration, 5) male tail morphology (rectrix length

and whether rectrices cross or not), and 6) male tail racket (“flag”)

coloration. Morphological characters of interest were: 1) bill length of

white-booted forms vs. buff-booted forms, 2) wing length of white-booted forms

vs. buff-booted forms, 3) rectrix length (and shape) of white-booted vs. melanantherus/peruanus vs.

annae vs.

addae, and 4) flag size of white-booted forms vs. peruanus vs.

addae/annae. Schuchmann et al (2016) provided

observations on the courtship display from four taxa: incommodus (of the white-booted group, N=17), peruanus (of the buff-booted group, N=11), annae (of the buff-booted group, N=6), and addae (of the buff-booted group, N>15), in

which incommodus had a three-stage display vs. a

two-stage display exhibited by peruanus, and a one- or two-stage display

exhibited by annae/addae. According to Schuchmann et al (2016,

these displays “broadly

correspond with the morphological groups, suggesting the existence of at least

three different groups (underwoodii/melanantherus, peruanus, annae/addae).” Finally, Schuchmann et al. (2016)

mentioned that a case could be made for sympatric

occurrence in eastern (Pogio, near Loja) Ecuador for melanantherus and

peruanus

based on specimen material, noting that the specimens of melanantherus

were of immatures, suggesting local breeding rather than vagrancy (which struck

me as an odd statement, as most hummingbird vagrancy seems to be done by

immatures!), but Zimmer (1951) dismissed this case suggesting instead that the

two immature melanantherus specimens were mislabeled.

Using

the Tobias scoring system, Schuchmann et al (2016) concluded that Ocreatus

contained four biological species: white-booted O. underwoodii, and the

buff-booted peruanus, annae, and addae. Schuchmann et al.

(2016) did not delve into vocal characters given that few recordings were

available on Xeno-canto or Macaulay at the time, and it wasn’t clear if the

vocalizations present were comparable (i.e., homologous).

New

Information:

A quick visit to our LSU collection confirms some of the issues outlined above,

and throws a monkey wrench in the works for others. Overall, I see agreement

between our specimens and the comments on ventral/boot coloration in both sexes

across the various populations represented. I also see the shortening of the

rectrices from northern to southern taxa as was pointed out in the paper. The

sticking point is that there appears to be a population that was not assessed

by Schuchmann et al (2016) from Cushi, in eastern Huánuco, and north into the

Cordilleras Divisoria and Azul (extending from SW Loreto and adjacent San

Martin south to eastern Huánuco and Ucayali depts). Interestingly, although the

authors acknowledge the LSUMZ collection in their paper, and specifically

mention the Cushi locality in their Appendix 1, they apparently did not review

the specimens therein very closely, as they overlooked this population, all

specimens of which should have been present during a revision of the LSUMZ collection

in preparation for this paper. This population appears to display intermediate

characters between peruanus and annae, including flags

intermediate in size and shape between peruanus and annae and

that are more iridescent blue than annae (more like peruanus),

rectrix length intermediate between peruanus and annae,

non-crossing racket-tipped rectrices (like peruanus; although the LSU

specimens are prepared such that this character cannot be assessed, I am basing

this character state on the following field images from the Cordillera Azul: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/205180711, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/205179041, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/611086271, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/603149731, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/171092391, but note that at

least occasionally, peruanus CAN cross its rectrices as seen here: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/513125041), annae

typically crosses its rectrices (e.g., near topotypical: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/242905071), and the outer web of

the longest rectrices are not paler-edged as in peruanus, but dark, more

like annae (a character mentioned by Zimmer 1951). It is unclear to me

if these specimens from Cushi and the Divisoria/Azul represent a named taxon

(possibly annae, type locality of which is Chanchamayo, Pasco), or not. Our holdings of male specimens from central

and southern Peru are rather sparse and do not answer this question adequately.

Interestingly, Schuchmann et al (2016) place the specimen from Cushi under the

name “annae” and one from “Fundo Cinchana”

(which appears to be near the “Abra Divisoria” locality of our LSU specimen) in

“peruanus” in their Appendix 1, suggesting that they didn’t detect that

these specimens were anomalous to their taxonomy, but rather considered them to

represent two different taxa!

Unlike

at the time of the writing of Schuchmann et al. (2016), the holdings of online

sound archives are much better with regard to voices of these taxa, and whereas

there is still little indication of what sounds can be best considered

homologous, I can, by ear, detect patterns that strongly suggest that the

white-booted forms (O. underwoodii by Schuchmann et al.’s designation)

are vocally fairly distinctive compared to buff-booted forms. To my ear, the

white-booted birds have a “springier” chase call (the rapid, descending trill)

that often accelerates over the course of one trill and tends to be

higher-pitched (e.g., https://xeno-canto.org/168323, https://xeno-canto.org/693722), whereas the

buff-booted birds have a lower-pitched chase call (e.g., https://xeno-canto.org/226843, https://xeno-canto.org/257059, https://xeno-canto.org/251277) with a tighter, more

even-pace (but can have variable speeds, probably depending on emotional

state). Flat-trill calls (usually given when perched or foraging unprovoked,

pers. obs.) are higher pitched in white-booted birds (e.g., https://xeno-canto.org/398384, https://xeno-canto.org/96236) and lower pitched in

buff-booted birds (e.g., https://xeno-canto.org/22910, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/513125041). However, within the

buff-booted forms, I cannot find any strong signal to suggest that there are

distinctive vocal groups. Unfortunately, the Bolivian addae, which

appears to have some of the strongest divergence in morphological characters

within this group, is unrepresented by recordings at the time of this writing;

however, I have heard it and was able to identify it as Ocreatus in the

field in Bolivia, suggesting it is not strongly differentiated from the

Peruvian buff-booted forms that I know well.

For

your listening pleasure:

White-booted

forms (O. underwoodii, sensu Schuchmann et al. 2016):

https://search.macaulaylibrary.org/catalog?taxonCode=boorat1&mediaType=audio&sort=rating_rank_desc&view=grid

https://xeno-canto.org/species/Ocreatus-underwoodii

“O.

peruanus”*:

https://search.macaulaylibrary.org/catalog?taxonCode=boorat2&mediaType=audio&sort=rating_rank_desc&view=grid

https://xeno-canto.org/species/Ocreatus-peruanus

“O.

addae”*:

https://search.macaulaylibrary.org/catalog?taxonCode=rubrat1&mediaType=audio&sort=rating_rank_desc&view=grid

https://xeno-canto.org/species/Ocreatus-addae

*

The division of recordings among taxa by both archives appears to contain some

error (for example, recordings from the Cordillera Azul are included under “peruanus”

when they seem best considered “annae” or perhaps an undescribed form,

based on the specimens I discussed above).

Recommendation: I think there is

enough evidence put forth by Schuchmann et al. (2016) to divide Ocreatus

into more than one species. However, I am not sure I agree that the complex

warrants four species based on the publication and on the specimens and

recordings I reference here. Between the plumage characters (boot tuft color

first and foremost) and the display details, I believe that we can comfortably

split the white-booted Ocreatus underwoodii (sensu Schuchmann et

al. 2016) from the buff-booted forms (peruanus, annae, addae). The

display behavior does not support division within the latter group, nor does

there seem to be strong vocal signal to suggest finer divisions therein. So it

falls on morphological characters to decide if the buff-booted forms require

further species-level separation or not. Personally, I am not convinced that

they do, particularly given the apparently intermediate population I mention

above from eastern Huánuco and the Cordillera Divisoria/Azul area. Therefore, I

recommend the following:

A. Split Ocreatus into white-booted (O.

underwoodii, including polystictus, discifer, incommodus,

and melanantherus) and buff-booted (O. addae, the oldest name,

including peruanus, and annae) species. I recommend YES.

B. Split buff-booted

forms into two species: northern O. peruanus and southern O. addae (including

annae), as per the current treatment by Clements’/eBird, IOC, and WGAC.

I recommend NO as per my reservations based on the Huánuco specimens discussed

above.

C. Split buff-booted

forms into three species: northern O. peruanus, central O. annae,

and southern O. addae, as per the treatment recommended by Schuchmann et

al. (2016). I recommend NO, for the same reasons as in “2” and the additional

reason that addae is lacking archived voice information at present.

English

names would have to be considered if any of these changes from a monospecific Ocreatus

should be adopted. The names already used by Clements’/eBird and IOC are:

White-booted

Racket-tail (O. underwoodii)

Peruvian Racket-tail (O.

peruanus)

Rufous-booted

Racket-tail (O. addae)

Schuchmann

et al. (2016) suggested Anna’s R-t (O. annae) and Adda’s R-t (O.

addae).

Should

we decide to follow recommendation 1 above and not split the buff-booted forms

any further, we could use “Rufous-booted R-t” as has been suggested by Ridgely

and Greenfield (2001).

References:

García,

N. C., K.L. Schuchmann, and P. F. D. Boesman (2022). White-booted

Racket-tail (Ocreatus underwoodii),

version 1.0. In Birds of the World (B. K. Keeney, Editor). Cornell Lab of

Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.boorat1.01

García, N. C., K.L. Schuchmann, and P. F. D. Boesman

(2022). Peruvian Racket-tail (Ocreatus peruanus),

version 1.0. In Birds of the World (B. K. Keeney, Editor). Cornell Lab of

Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.boorat2.01

García, N. C., K.L. Schuchmann, and P. F. D. Boesman

(2022). Rufous-booted Racket-tail (Ocreatus addae),

version 1.0. In Birds of the World (B. K. Keeney, Editor). Cornell Lab of

Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.rubrat1.01

Gill,

F., D. Donsker & P. Rasmussen (Eds). 2024. IOC World Bird List (v14.1). doi :

10.14344/IOC.ML.14.1. (accessed 5 January 2024)

Ridgely, R. S., and P.

J. Greenfield (2001). The Birds of Ecuador: status, distribution, and taxonomy.

Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Schuchmann, K. L.,

Weller, A. A., and D. Jürgens (2016). Biogeography and taxonomy of racket-tail

hummingbirds (Aves: Trochilidae: Ocreatus):

Evidence for species delimitation from morphology and display behavior. Zootaxa

4200:83–108. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4200.1.3

Zimmer, J. T. (1951)

Studies of Peruvian birds. No. 61. The genera Aglaeactis, Lafresnaya,

Pterophanes, Boissonneaua, Heliangelus, Eriocnemis, Haplophaedia, Ocreatus, and Lesbia. American Museum

Novitates 1540. http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/bitstream/handle/2246/3700//v2/dspace/ingest/pdfSource/nov/N1540.pdf?sequence=1

Dan Lane, January 2024

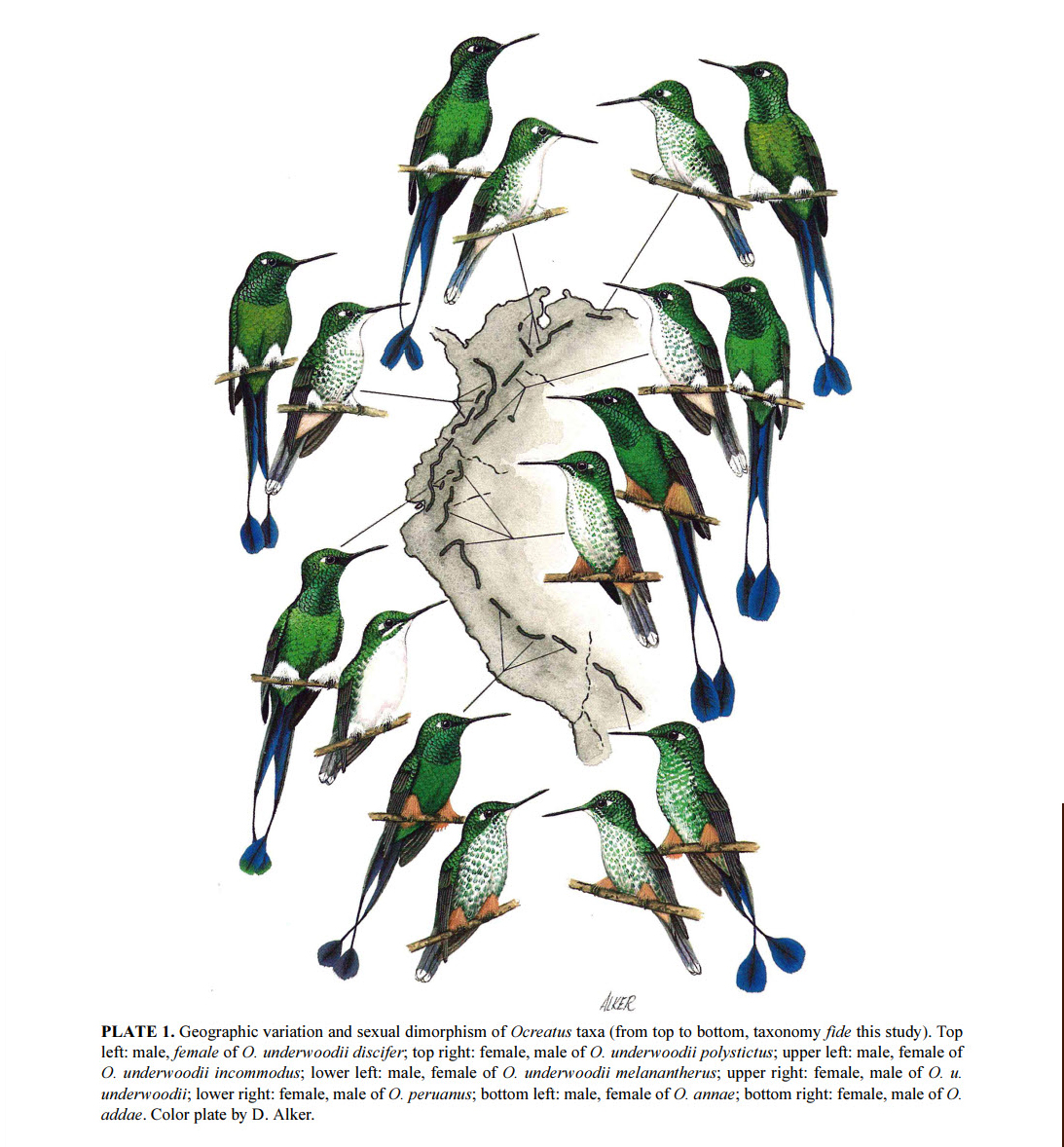

Fig

1. Plate 1 from Schuchmann et al (2016) showing illustration of the different

taxa within Ocreatus, and demonstrating important morphological characters.

Note particularly boot color, male tail length, flag shape and color, and

whether rectrices cross or not.

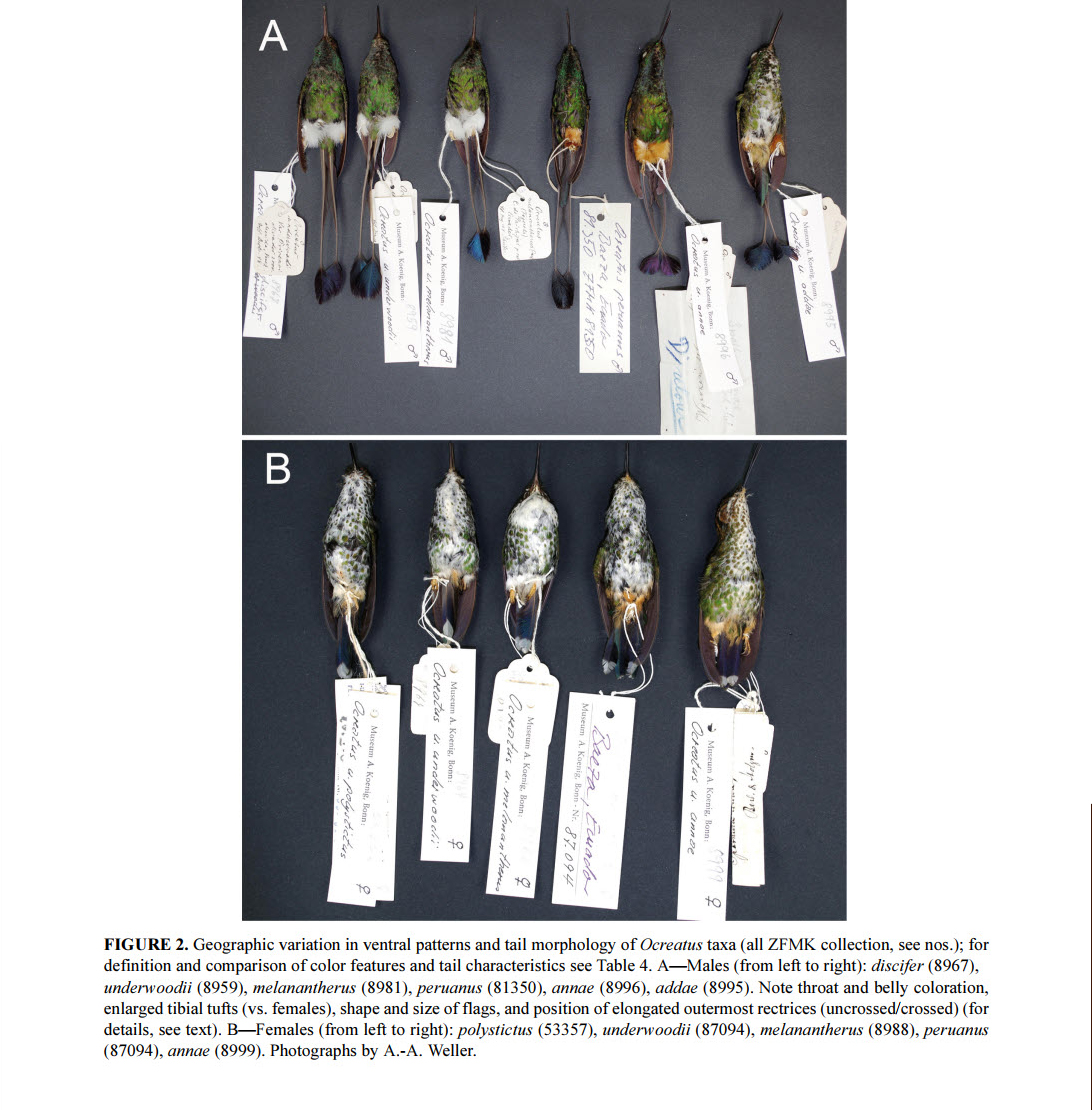

Fig

2. Figure 2 from Schuchmann et al (2016) showing specimens of selected taxa,

including both male and female plumages.

Fig

3: Males of buff-booted forms from Peru and Bolivia, LSUMZ collection. A: peruanus

from San Martin dept (near type locality). B: specimen from Cordillera

Divisoria, Huánuco dept. C: specimen from Cushi, Huánuco dept. D: annae

from Cusco dept. E: addae from La Paz, Bolivia. Photo by D. F. Lane.

Comments

from Zimmer:

“A. YES, for reasons

nicely summarized by Dan. I think the

distinctiveness of the boot-color differences provides an obvious signal,

reinforced by noted display differences.

After listening to archived vocal samples of white-booted birds versus

buff-booted birds, I would agree that the vocal distinctions are also

supportive of splitting these two groups.

“B. NO, based on the

seemingly intermediate specimens cited by Dan in the Proposal, and the lack of

obvious (at least to my ears) vocal differences or display differences.

“C. NO as per my reasons

for voting NO on Part 2, and given that there are no archived vocal samples of

Bolivian addae for comparison with the other buff-booted taxa.

Comments

from Areta:

“In principle, even with notable gaps, the

two-species treatment makes sense, but I will vote NO given several problems,

missing data, and uncertainties.

“The morphological and plumage evidence suggests the existence of

clinality in several features (discussed by Schuchmann et al. 2016). As per the

behavioral data, I am not convinced that the lack of the "whip phase"

(phase C) in the short-tailed forms has been sufficiently corroborated (see

Schuchmann et al. 2016:101 and Schuchmann

1987). For example, intensity and completeness of displays might be

contingent upon the stage of the breeding season, and studying complex

phenotypes for reduced periods of time might not provide thorough descriptions

of displays. Because the last phase apparently leads to copulation, it is

expected that not all the displays will end in this behavior. We don´t have

information on periods of time or places in which these displays were seen.

“The vocal data shows that some calls (whose role in mating is

possible non-existent) seem to differ in pitch. This adds another line of

support on the differentiation between buff-booted and white-booted forms, but

it falls short to show vocal differentiation relevant to mating. Also, note

that the name that takes precedence is addae, but there

are no recordings for this buff-booted distinctive taxon.

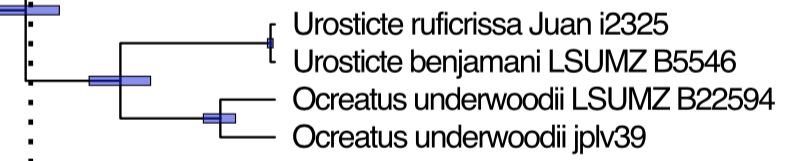

“See the relevant part of the tree from McGuire et al. (2014),

which is perhaps the best available genetic evidence, but only includes one

white-booted and one buff-booted taxon, from distributional extremes. The JPLV

sample, which should be JLPV after Juan Luis Parra Vergara [thanks to T.

Schulenberg for working this out], is from Cundinamarca, Colombia, therefore

incommodus? The LSUMZ

sample is from La Paz, Bolivia therefore

addae. The dotted line is at 10

my.”

“This is a case in which more fieldwork, formal bioacoustic

analyses, and genetic analyses are needed to properly assess the taxonomy of

these wonders.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“NO to A, B, and C. I agree with Nacho on all points.

Definitively, genetic data and formal vocal analyses are needed to decide.

Also, a better taxonomic covering regarding displays and probably, more

observations, would further support the case. This is a nice

group of taxa for which a complete phylogeographic analysis is still pending.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“NO for reasons stated above, but additionally for a new wrinkle in the

tapestry – a recently discovered population of buff-puffed birds in the

Serranía de San Lucas, the northernmost spur of the Central Andes of Colombia.

Andrés Cuervo et al. will hopefully obtain genetic data on these (n=3), but

until these are analyzed, it´s impossible to know which (if any) apple carts

might be upset.”

Comments

from Lane:

“I suppose it's no surprise that I'd go with my own

recommendations on this and say YES to 1, and NO to 2 and 3 here. The voice and

plumage distinctions are sufficient for me to feel that a split is warranted.

The news of a new buff-booted form in Colombia doesn't really change that for

me, as it might not be related to the addae group at all. Also, if addae is

distinct from the remainder of the southern buff-booted birds, we can always

act on that once the evidence is provided. Meanwhile, the split seems a

reasonable one to me.”

Comments from Claramunt: “A. YES. At the very least we have two differentiated species here:

white-booted and buff-booted. I am forced to vote NO to B and C as they are

worded, given the existence of intermediate populations revealed by Dan that

suggest that peruanus and annae are not clearly separable. But if given the

chance, I would give species rank to addae, given its distinctiveness in both

male and female plumages, including coloration and tail morphology.

Comments from Niels Krabbe (voting for Robbins): “NO to A,

B and C for the reasons given by Areta. Of all the different characters of the

taxa, only the differences in display strike me as being of more than

subspecific value. Schuchmann et al.'s (2016) sample sizes of observed displays

(17, 11, 6, >15) seem impressive, but do they represent different

individuals, and do they not just reflect levels of excitement?”

Comments from Remsen: “NO to all, echoing especially

the concerns of Nacho and Niels. I

suspect that a two-way split will be justified with more evidence, but I think

a cautious approach at this point is best.

This system deserves a thorough study.

Philosophically, I think this is a good example of why rejected

proposals are in one way more valuable than accepted ones – they not only

provoke additional research to make sure we maximize evidence before making a

taxonomic decision that would potentially signal ”case closed”, but they also

set the stage for additional research by pointing out exactly what we need to

know. This one is a good example – Dan has

laid it all out here in a great proposal that will jump-start further research.”