Proposal (994) to South

American Classification Committee

(Note from Remsen: This proposal was submitted to the North American

Classification Committee and passed, and it is submitted here with permission

from Terry Chesser. This is an

extralimital split, but we have to deal with it because it affects the English

name we use.)

Treat Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis as two species

Background: Most global lists (e.g., eBird/Clements, IOC,

Howard & Moore) have traditionally considered Bubulcus ibis to be a single species with two subspecies: ibis of southern Europe, Africa, Asia

Minor as far east as Iran, and the Americas; and coromandus of South Asia and southeastern Asia south to Australia

and New Zealand. These two subspecies are separated by a gap in distribution in

Pakistan and Afghanistan. A third subspecies, seychellarum of the western Indian Ocean, is sometimes recognized

(e.g., by Birdlife); otherwise, these populations are considered part of ibis.

The IOC list recently elevated coromandus to species status,

recognizing two species in this complex. Their note on this change is as

follows: “Bubulcus coromandus is

split from B. ibis (Payne &

Risley 1976; McAllan & Bruce 1989; Rasmussen & Anderton 2005). Status

under discussion (Christidis & Boles 2008; Ahmed 2011; HBW).”

The relevant passage from Payne and Risley

(1976), who placed this species in Egretta,

is here:

“Cattle

Egrets of Africa (E. i. ibis) and

India (E. i. coromanda) have very

different breeding plumages and might better be regarded as two species or at

least two allospecies of a superspecies. African birds have orangish-buff

display feathers coloring the entire head, neck, and upper breast; long plumes

of similar color cover the lower back and rump. Indian birds have pinkish-buff

plumes and these are restricted to the crest, the upper breast, and the lower

back; the neck and throat are white. The bill is shorter and stouter in ibis. The extent of feathering on the

tarsus above the distal tarsometatarsal joint is greater in ibis (about 12 mm bare tarsus) than in coromanda (about 24 mm bare tarsus), but

some overlap occurs between specimens of the two groups. Wing lengths differ on

the average (Ali and Kipley, 1968; Mackworth-Praed and Grant, 1970) but the

ranges of wing lengths overlap. The two forms are geographically separated from

each other. Cattle Egrets of the Seychelle Islands have been regarded as intermediate

between the Indian and African birds, but only one specimen in breeding plumage

is known, and it has not been possible to test further the idea that Seychelle

birds (described as a subspecies "seychellarum")

are hybrid results of independent invasions and establishments on the islands

from Africa and India (Benson and Penny, 1971). It is possible that the

differences in breeding plumage would act as behavioral isolating mechanisms

between the two forms of Cattle Egrets, and it would be of interest to

complement the study of behavior of African birds (Blaker, 1969a) with a study

of behavior of birds in India or Australia. Examination of skeletons in the

present study showed no differences in the coded character states in the two

forms, though the interorbital foramen was slightly more rounded anteriorly in

the African specimens.”

McAllan and Bruce (1989), referenced in the IOC

note, is a working list of the birds of New South Wales, Australia. They

presumably recognized B. coromandus as

separate from B. ibis, whereas

Christidis and Boles (2008) presumably treated them as conspecific in their

list of Australian birds.

Volume 1 (Field Guide) of Rasmussen and Anderton

(2005) stated that Western Cattle Egret B.

ibis is “similar but stockier [than B.

coromandus], in breeding plumage with orange-buff mainly on crown, breast,

and mantle.” In Volume 2 (Attributes and Status), they expand on this as

follows:

“[Western Cattle Egret is] Like Eastern but smaller and stockier, with shorter

bill, neck and legs (latter often paler yellowish, olive or grey, but

never black), less bare facial skin and puffier ‘jowls’. Breeding adult

shows a shaggier, paler peach-colored crest only on top of

head, finer, more hair-like peach breast-plumes, and brighter red legs. In

flight, less leg extension than for Eastern….Size Length 330-380 [340-370 in coromandus];

head 90-100 [97-110 in coromandus];

tail 80-90 [81-93 in coromandus];

bare leg 168-180 [205-225 in coromandus]….

Habits Much as for Eastern. Voice Calls noticeably

higher-pitched, more nasal and less gravelly than Eastern’s.?

The Birdlife rationale for continuing to

recognize only a single species was as follows:

“Race

coromandus

The only formal study of phenotypes appears to

be that of Ahmed (2011), a paper published in Dutch Birding and directed

towards identification of potential vagrant coromandus

in the Western Palearctic. He concluded that

“the following features are useful in separating ibis and coromandus: 1 extent

and coloration of adult summer plumage; 2 bill length; 3 tarsus length; 4 tail

length; and 5 bill depth at both nostril and feathering (only in separation

of ‘Indian Ocean specimens’ from ibis and

coromandus). In addition,

vocalisations are of use according to Rasmussen & Anderton (2005) but data

on these were not collected and they require further work. Data to confirm the

validity of the taxon ‘seychellarum’

and its separation from ibis and coromandus are lacking.”

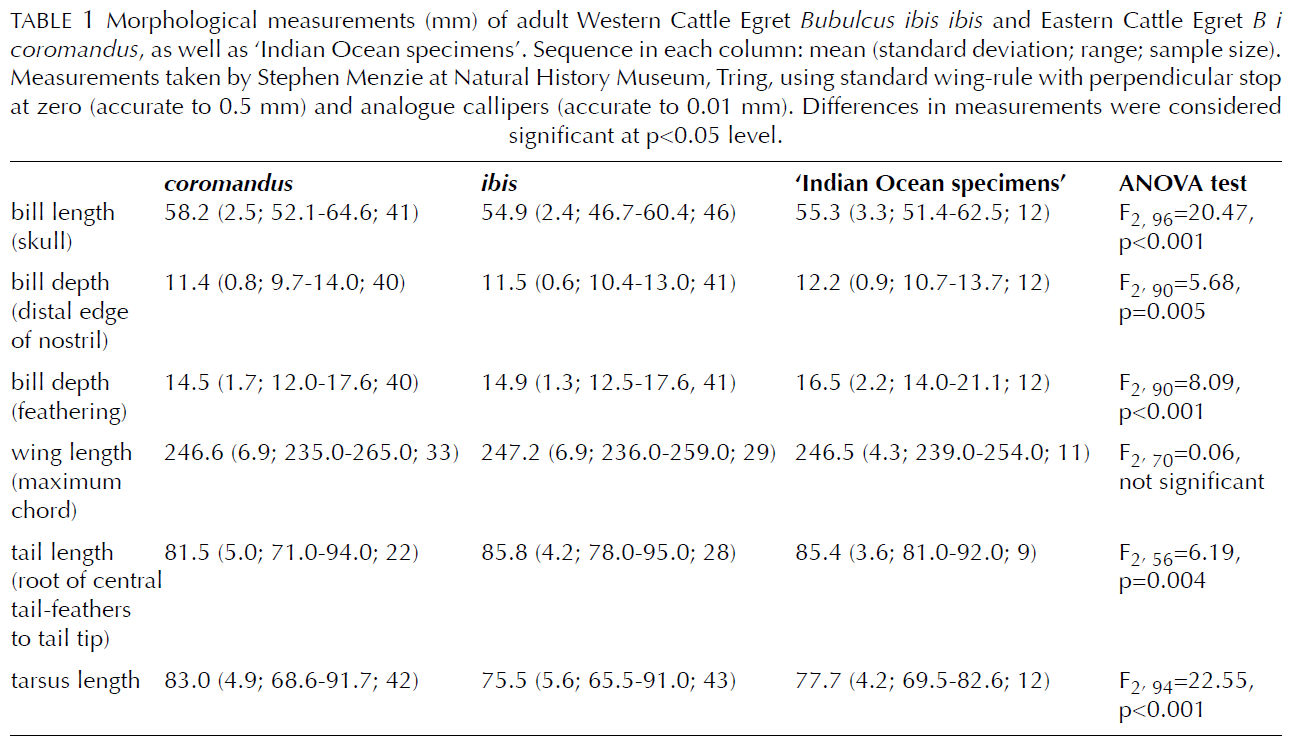

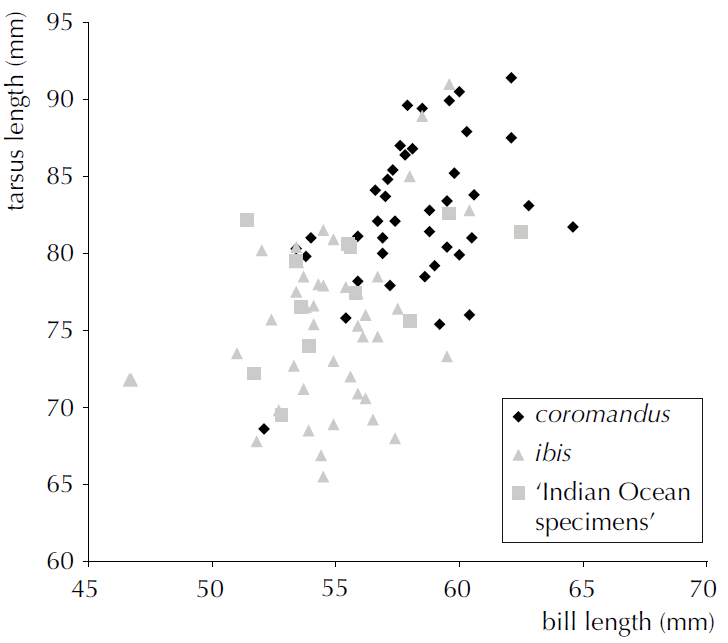

However, although breeding plumage is readily

diagnostic, the morphometric characters listed above, as noted in the Birdlife

spiel as well as by Payne and Risley (1976) and Ahmed (2011), show a fair

amount of overlap (see Table 1 and Fig. 3 from Ahmed 2011 below).

Ahmed (2011) also questioned the vocal

differences discussed in Rasmussen and Anderton (2005), noting that Sangster

(in litt.) could find no differences in vocalizations and that Kushlan and

Hancock (2005) mentioned up to 11 call types. He suggested that the calls

compared by Rasmussen and Anderton (2005) may not have been homologous. I’m not

aware of any further discussion of the vocalizations.

Fig. 3 from Ahmed (2011), plotting bill length

versus tarsus length in the two subspecies of B. ibis, with Indian Ocean populations (“seychellarum”) also separated.

Somewhat surprisingly, no genetic studies have

included both subspecies of B. ibis.

Hruska et al. (2023), for example, included only a sample of subspecies ibis from Louisiana.

New Information:

As part of an effort to consolidate global bird

lists, the IOU’s Working Group on Avian Checklists (WGAC) recently considered

whether to separate B. ibis into two

species. WGAC voted to recognize B.

coromandus as a separate species from B.

ibis. This change has already been adopted in the most recent Clements

update and as noted above, was previously adopted by the IOC list.

Members of WGAC who voted for the split

emphasized the differences in breeding plumage, which involve not only the

extent of the buff coloration but also the color and texture of the plumes.

Also mentioned were differences in shape and proportions, although the

morphometric data do show overlap. The lack of clinality in the plumage

differences was also viewed as significant: breeding plumages of the

westernmost individuals of coromandus and

easternmost individuals of ibis were

noted to be the same as those elsewhere in their respective ranges. Those

voting against the split were not convinced that the differences between coromandus and ibis are more than subspecies-level distinctions, and preferred to

wait for additional data bearing on species status.

Recommendation:

Although I voted against the split, this is

primarily an Old World issue and I recommend that we adopt the new global

taxonomy for this complex, following our standard policy. Most “Old World”

representatives on the WGAC voted for the two-species arrangement. Despite

evidence that may fall short of our usual standards, I would recommend adopting

the new global taxonomy of recognizing B.

coromandus as a species separate from B.

ibis.

English Names:

Both the IOC and eBird/Clements lists are using

Western Cattle Egret for B. ibis and

Eastern Cattle Egret for B. coromandus.

I would recommend that we also use these names, although our guidelines

indicate that the group name should be Cattle-Egret, to indicate their status

as sister species, rather than Cattle Egret.

References:

Ahmed, R. 2011. Subspecific identification and status of Cattle Egret.

Dutch Birding 33: 294-304.

Christidis, L., and W. Boles. 2008. Systematics and Taxonomy of

Australian Birds. CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Victoria, Australia.

Hruska, J. P., J. Holmes, C. Oliveros, S. Shakya, P. Lavretsky, K. G.

McCracken, F. H. Sheldon, and R. G. Moyle. 2023. Ultraconserved elements

resolve the phylogeny and corroborate patterns of molecular rate variation in

herons (Aves: Ardeidae). Ornithology 140:

ukad005 doi.org/10.1093/ornithology/ukad005

Kushlan, J. A., and J. A. Hancock. 2005. The Herons. Oxford University

Press, Oxford, U.K.

McAllan, I. A. W., and M. D. Bruce. 1989. The Birds of New South Wales, a Working List.

Biocon Research Group, Turramurra, NSW, Australia.

Payne, R. B., and C. J. Risley. 1976. Systematics and evolutionary

relationships among the herons (Ardeidae). Miscellaneous Publications of Museum

of Zoology 150: 1–115.

Rasmussen, P. C., and J. C. Anderton 2005. Birds of South Asia: The

Ripley Guide. Smithsonian Institution Press/Lynx Edicions, Washington, DC.

Terry Chesser,

March 2024

Note from Remsen on English names. Unless someone wants to write a proposal on

English names with some better names than Eastern and Western, I suggest that

we just go with those to be consistent with NACC and others.

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“YES - I vote to split. We have an issue with herons

and egrets, in that differences and sometimes striking differences, are not taken into account as strongly in birds like these that are

uniform in plumage. White birds, or we could go to Corvus for the

opposite, or Quiscalus. These groups have multiple seemingly

species-level taxa that are cryptic. I am not sure voice is really all that

important in these colonial egrets and herons, in the way it is in bitterns who

use voice as a primary means of attraction and display. We have the

Intermediate Egret system, the Great Egrets, and even the Great White Heron

situation that include some major differences, in display coloration of soft

parts, ecology etc that suggests some barriers to interbreeding. But I guess

our eye goes to the largely white plumage and we stay there. In this case we

have a big difference with their striking difference in breeding plumage, with

extent of color, strength of color, and as noted some of the structure of the

feathers. I think this is important. Similar to the head coloration in Cathartes

vultures, the birds are using these features to sort themselves out. So, I am

fine with a split on the Cattle Egrets.”

Comments from Del-Rio:

“YES. I think plumage differences in breeding forms are pronounced

enough for the separation. Size differences are not as compelling though.”

Comments from Claramunt: “YES. All the evidence points to

separate species. The difference in breeding plumage is remarkable, no

intermediates are known, and the difference has the potential to influence

species recognition. The overlap in morphometrics is not that relevant; sister

species tend to overlap widely in morphometrics.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“YES. The evidence for the split is borderline, but if the WGAC (especially its

Old World members) approved it, I will go along with this.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“YES (but hesitantly). The breeding plumages are different. If that is any

indication of reproductive isolation, it is a good reason to split them.

However, these are the kinds of differences that we consider “subspecific” in

other birds. If there are no intermediate specimens, that could be because they

do not exist, or because the places where they could meet (Pakistan and

Afghanistan) have been rarely sampled. I am also uncomfortable with a split

with no genetic data, but perhaps the taxonomy of the cattle egrets should not

be a big concern. If somebody finds out later that they are conspecific, we

just lump them back again without any major consequences.”

Comments

from Robbins:

“NO. I find current data not to be compelling for recognizing these two egrets

as separate species. For example, I do

have experience with “Eastern” and in at least some populations it does have

black legs (have photos on my eBird checklists that document that) contra what

R & A (2005) state, “never black”.

Moreover, I also question other morphological statements based on my

experience. It should be noted what is attributed in this proposal to the

Birdlife rationale that also contradicts R & A statements on differences in

morphology. The comments on

vocalizations by Ahmed (2011), contra R & A, should also raise a red

flag. I want to see a genetic data set

from across the range of “Eastern” as compared to “Western” before a taxonomic

change is made.”

Comments from

Areta:

“I vote NO to the split. I

would like to see more compelling evidence. The current differences in plumage

(breeding plumage differences especially, other features seem less reliable)

shown do not allow me to judge whether a two-species taxonomy is an improvement

over a single-species taxonomy with subspecies. There is ample morphological

overlap as well. A better study can do no harm, so I prefer to wait for it in

order to revise this position. This is a contentious issue that needs to be

properly studied.”

Comments from Remsen: “NO. These are all

interesting observations on the differences between the two taxa, but they are

largely anecdotal and disputed (voice, texture of breeding plumes ) and the

measurements overlap. That leaves

breeding coloration. I’m not sure this

marks the “point of no return” in restricting gene flow heron speciation. Certainly, we have color morphs within some

species (Egretta rufescens, E. sacra, E. garzetta) that suggest

that major differences in plumage coloration are not barriers to gene

flow. On the other hand, we have Ardea

herodias/A. occidentalis that mate assortatively at their contact

zone (yet continue to be treated as conspecific by NACC), for which the only

difference is coloration and thus contradict the point made about color morphs. For better or worse, global Butorides

striatus taxa ranked as subspecies differ at least as much in plumage from

each other as do the two Cattle Egret taxa.

Nycticorax caledonicus also.

In my view, species limits in allotaxa in the Ardeidae is an

inconsistent mess with not many “knowns” in terms of contact zones in

parapatric taxa to provide any guidelines.

So, strictly as a matter of principle, I don’t think we should be

changing long-standing species limits without a better empirical and

theoretical framework.”

As

pointed out to me by Murray Bruce, Vaurie (1963, BBOC, “Systematic notes on the

Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis)” was one of the few people who really

studied specimens; he did not make a recommendation to treat them as separate

species but provided a good synopsis of the differences:

“Tangentially,

Vaurie makes the point that I’m sure we’ve all pondered. Why is there such a big gap in distribution

between these two taxa, which have expanded dramatically with the spread of

livestock and agriculture, and which are notoriously good at dispersing, most

notably in crossing the Atlantic?

“I

appreciate that good field people familiar with coromandus say that it

flies differently and has a different “look”.

Maybe after just a day of field experience I would be impressed by these

differences. Nonetheless, the actual

data for changing the taxonomy is weak at best.

In a comparative context, I can’t think of another pair of sisters in

herons that differ solely in extent of a single color in the plumage during the

breeding season. I’d be more impressed

if there were differences in breeding facial coloration and bill color, but

even those differences are on both sides of the species/subspecies line in

current taxonomy.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“I change my vote to NO in light of the other comments. My YES was reluctant,

anyway.”

Comments from Zimmer: “NO. I would echo some of the same caveats already

presented by Mark, Nacho, and Van on this one.

The distinctions in breeding plumage between ibis and coromandus

are suggestive, but I would find them much more compelling if there was also

clear-cut evidence of difference in bare parts coloration when in peak breeding

condition. To me, the differences in

facial skin coloration, bill coloration and tarsus & toe coloration are

among the most dramatic morphological changes in this group of birds tied to

the peak of breeding condition. Changes in the colors of these bare parts are

not only dramatic, but are highly seasonal, and highly ephemeral, and are

coincident with “peak breeding condition”, which would seem to make them all

the more likely to be important as isolating mechanisms and in mate

selection. There may, indeed, be

distinctions in bare parts colors between ibis and coromandus,

but, if so, I don’t see any indication of it in the Proposal or in any of the

excerpts from the relevant literature cited therein, and my own field

experience with coromandus is too seasonally limited to say.”

Comments from Lane: “YES, although it’s

mostly because this is an Old World issue, and the result is immaterial to the

SACC region. As others have mentioned, I am not sure what characters are

informative in many heron species limits cases, so if this pair truly is that

distinctive or not is not clear to me. There are simply too few recordings of B.

coromandus to have any useful idea of how similar or different they are

from B. ibis (especially given the dilemma of homology of vocalizations?).

However, I have been thinking that, if the split is to be, we could maintain

“Cattle Egret” for B. ibis, and use “Buffalo Egret” for B. coromandus,

given that is the Bos species they probably evolved alongside (that is

only partly tongue-in-cheek).”