Proposal (1001) to South

American Classification Committee

Treat Eudyptes filholi as a

separate species from E. chrysocome

Note:: This is one of

several situations that the IOU Working Group on Avian Checklists has asked us

to review. I have no first-hand

knowledge of this situation, so my goal here is to lay out the critical facts

of potential relevance to taxonomy just to get the discussion started. I hesitated to do this one, because the

potential new species is extralimital, and also because the post-retirement

pruning of my library has reduced the number of independent references I can

check..

Effect on SACC: Passage

of this proposal would not affect current SACC classification in any way except

by constricting the range of what we treat as Eudyptes chrysocome.

Background: Our

current SACC note is as follows (which I need to update to include Frugone et

al. (2021):

8. Jouventin (1982),

Jouventin et al. (2006), and Banks et al. (2006) demonstrated that moseleyi,

traditionally treated as a subspecies of E. chrysocome, differs in voice

and mating signals from, and is moderately differentiated genetically from, chrysocome. SACC proposal passed to treat moseleyi

as a separate species. For English names for

this species pair, see SACC Proposal 516. The two species were called “Northern

Rockhopper Penguin” (moseleyi) and “Southern Rockhopper Penguin” (chrysocome)

in Dickinson & Remsen (2013) and del Hoyo & Collar (2014). For additional support for treatment as

separate species, see Mays et al. (2019).

Eudyptes moseleyi is a vagrant to the SACC region

based on occurrences in the Falklands/Malvinas, and a 2019 record on the

coast of Rio Negro (northern Patagonia), Argentina (fide Mark Pearman); it breeds

on islands in the Southern Oceans, e.g. Tristan da Cunha, Gough, St. Paul,

Amsterdam). Eudyptes chrysocome

breeds on the Falklands/Malvinas and islands off S. Chile. The taxon filholi Hutton, 1879, is

currently treated (e.g. Dickinson & Remsen 2013, del Hoyo & Collar

2016, IOC, Clements) as a subspecies of E. chrysocome. It breeds on several island groups (e.g.,

Crozet, Kerguelen, Heard, Macquarie, Auckland) in mainly subantarctic waters in

the southern Indian Ocean and off Australia-New Zealand, i.e., on the other

side of the planet from nominate chrysocome; however, despite that

distance and gap in breeding distribution, it differs only in minor phenotypic

characters from nominate chrysocome, primarily in having the narrow

lower margin of the mandible pale fleshy pink instead of orangey like the rest

of the bill. Below are photos from

Macaulay Library; see also photos in Howell and Zufelt (2019):

Eudyptes c. chrysocome,

Falklands/Malvinas, by David and Kathy Cook (ML 205735341, flipped and slightly cropped):

Eudyptes c. filholi, Heard and

McDonald Iss., by Robert Tizard (ML343435611 slightly cropped):

For comparison, here is Eudyptes

moseleyi, with its considerably more flamboyant plumes, a returning vagrant

to the Falklands/Malvinas, by Alan Henry (ML 186628281).

Of interest is that Alan Henry noted that this bird was “Returning bird first seen in 2014. Paired with Southern

Rockhopper Penguin, sitting on single egg” https://ebird.org/checklist/S61273479 and the

same list reports hybridization there with Macaroni Penguin (E. chrysolophus). EBird, by the way, calls this “Moseley’s

Rockhopper Penguin” not Northern Rockhopper Penguin.

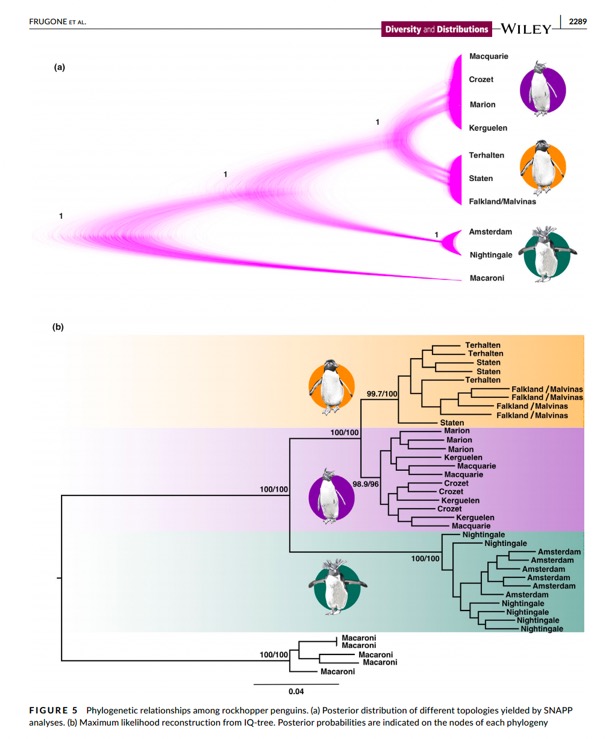

New information: Frugone et al. (2021) through a

sophisticated genetic analysis showed that all three taxa represented separate

lineages, whereas the different island populations sampled within each taxon

did not. Note that genetic distance

roughly corresponds to degree of plumage differentiation, with Eudyptes

chrysolophus (Macaroni Penguin) sister to the other three, and filholi

and nominate chrysocome the least differentiated genetically.

The “species delimitation” analysis

that the authors used implicitly delimits species under the General Lineage

Species Concept, not the BSC. Note that

under this method of “species” delimitation any degree of differentiation of

allopatric taxa would find them to be “species.”

“In summary, at the molecular level,

several lines of evidence support recognition of three species of rockhopper

penguins: 1) genomic differentiation among E. moseleyi, E. chrysocome

and E. filholi substantially exceeds differentiation observed within

each taxon; 2) there is no genomic evidence of admixture or hybrid individuals

among these taxa; 3) our analyses suggest no contemporary gene flow among the

three taxa; and 4) species delimitation analyses strongly support a

three-species designation to the exclusion of a model designating E.

chrysocome/E. filholi as conspecific. Our results, thus,

confirm the findings of previous studies revealing reciprocal monophyly with

mtDNA markers, supporting this three-species designation (Banks et al., 2006;

Cole, Dutoit, et al., 2019; Cole, Ksepka, et al., 2019; de Dinechin et al.,

2009; Frugone et al., 2018; Mays et al., 2019).”

The authors are quite aware of this

issue and go on to discuss factors relevant to BSC criteria, e.g. voice and

display. They noted that whereas moseleyi

is known to have different vocalizations from the other two, no such

differences are known between nominate chrysocome and filholi. With respect to filholi:

“ … whereas

the main morphological differentiation between the sub-Antarctic taxa

corresponds to a more pronounced pink to white gape (bare skin around the bill)

on E. filholi which is black on E. chrysocome (Tennyson &

Miskelly, 1989). Other morphological features differentiating E. filholi

from E. chrysocome include a narrower bill and the shape of the black

mark on the undersurface of the apex of the wing (Hutton, 1879). Finally,

vocalizations are an important behavioural trait in penguins, since they may

rely more strongly on auditory cues for mate selection and individual

recognition than on morphological characters (Aubin & Jouventin, 2002;

Jouventin et al., 2006; Searby & Jouventin, 2005). Differences have been

found in the mating calls of E. moseleyi in comparison with those of E.

chrysocome (when considered a single species to E. filholi),

providing an additional line of evidence for delimiting those taxa (Jouventin

et al., 2006). However, as far as we know, vocalizations of E. chrysocome

and E. filholi have not been directly compared and should be a priority

for future data collection and study.”

Discussion

and recommendation:

In my view, this boils down to philosophy and species concepts. Three distinct lineages are involved. The split between moseleyi and chrysocome+filholi

is marked by vocal differences and reasonably dramatic plumage differences from

which we can infer, for better or worse, that they have diverged to the point

that free gene flow would no longer be possible. That vagrant moseleyi can pair with

and at least produce eggs with Falklands chrysocome is not evidence for

free gene flow. That filholi and chrysocome

have not diverged to the point of developing differences in characters

considered to be important in penguin mate selection means that under the BSC, they

are best considered subspecies of the same species. Further field research on that should be

encouraged, as suggested by the authors, and should be straightforward. If these penguin colonies are visited to

census them and gather blood samples, then why doesn’t someone do some

recording of vocalizations?

Frugone

et al. (2021) advocated for species rank in part to aid conservation

measures. Emotionally, I am sympathetic

to this, but objectively, I urge extreme caution in letting this influence a

scientific decision. Otherwise, we and

others making such taxonomic decisions will undermine our credibility and make

ourselves vulnerable to accusations of advocacy, a point made by

anti-environmental groups.

All

in all, I recommend a NO on this one, especially since additional evidence

would seem so readily obtainable given that these remote islands are indeed

visited by penguin biologists. If

recordings of vocal display reveal substantial differences, then that would

change my vote immediately to a YES.

English

names: Frugone et al. (2021) used “Northern

Rockhopper Penguin” and “Southern Rockhopper Penguin” as in SACC and elsewhere,

and use “Eastern Rockhopper Penguin” for filholi. If the proposal passes, I think we need a

separate proposal on English names. Keep

in mind, as Mark Pearman just reminded me, that we voted to avoid those longer

names by going with “Tristan Penguin” for moseleyi and retain

“Rockhopper Penguin” for the more widely distributed and more familiar chrysocome

s.s. (SACC 516).

References (see SACC Bibliography for standard

references)

Frugone MJ, TL Cole, ME

López et al. 2021.

Taxonomy based on limited genomic markers may underestimate species diversity

of rockhopper penguins and threaten their conservation. Diversity and

Distributions. 27: 2277–2296.

Howell, S. N. G., and K. Zufelt, 2019.

Oceanic Birds of the World. A Photo Guide. Princeton University Press.

Van Remsen, June 2024

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Vote tracking chart:

https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart968-1043.htm

Comments

from Stiles:

“Again, NO until data on the vocalizations and mating displays of filholi become

available.”

Comments from Areta: “NO. This was

my WGAC vote, which I repeat here: " I vote NO to the split of filholi.

To me, this study has shown evidence on the validity of filholi as a

subspecific taxon. The case is quite borderline from my perspective. The

authors are careful regarding the meaning of their work, even when they endorse

the split. I´d rather wait for evidence regarding vocalizations. The degree of

genetic differentiation is on the lower end of the genus. I am happy with the

conservative stance here, although I acknowledge that the split might be seen

with good eyes by others."

Comments from Claramunt:

“YES. A difficult borderline case. I base my decision

on the fact that these penguins show facial differences that are not only

diagnostic, but that can play a role in species recognition. The light margin

at the base of the bill in filholi is distinctive.”

Comments from Robbins:

“NO. This is indeed borderline on whether to recognize as filholi as a

species. I’m fine waiting until the vocal data are obtained that might turn

this into a straightforward decision.

So, for now NO.”

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“YES – I am with Santiago on this one, apart from plumes facial features and particularly

pink skin around bill differs in species of penguins. Spheniscus for example

are readily identifiable on pink skin distribution, in addition to how many

dark bands they have on the breast. It is a borderline case, but these lineages

are separate, and vagrant penguins do happen, actually quite regularly. I

gather that the genetic work did not find any possible gene flow, so that is

important.”

Comments

from Pearman (voting for Remsen): “NO. I’m not

impressed by vocal differences between recordings of chrysocome and filholi that I have

listened to, which is in contrast to the radically different moseleyi vocalizations. I

also note that several authors urge caution over the field identification of filholi from chrysocome due to variation in the thickness of the supercilium and

extension of head plumes. Adding to this, the recently published marginal

genetic divergence tips the scales towards maintaining subspecific status for filholi under the BSC.

Comments from Louis Bevier (voting for Bonaccorso):

“NO. While the single morphological character

separating filholi and chrysocome, pink gape and stripe along

bottom of mandible in filholi, is rather distinctive and may be

important, a quick comparison of vocalizations suggests to me that filholi

and chrysocome are rather similar, especially compared to moseleyi

(Northern) and why that previous split was well-supported. Thus, I agree with

others that analysis of vocalizations and associated behaviors is needed before

we can make a decision in this case.

“I had fun listening to squawks and brays and barks for the three

taxa. Ted Parker has a two long, good cuts from the Falklands of chrysocome,

including a point where he says, "duetting birds." With that as a

baseline, I compared a few recordings of filholi (Doug Gochfeld has some

and my Birds of New Zealand app has one recording) and moseleyi (one

recording on xeno-canto of birds said to be squabbling, so not the same

courtship context). To me, filholi and chrysocome are similar,

whereas moseleyi is clearly different (deeper and lower), which we

already knew. Given this, I would need to see how Jouventin et al. analyzed the

vocalizations and associated behaviors to get a sense of whether those

characters will prove helpful. A cursory listen suggests filholi and chrysocome

might not differ that much, but clearly someone needs to do the analysis in a

rigorous way and compare behavior of courting birds.

“I also skimmed through the genetics papers, Frugone et al. (2021)

and Mays et al. (2019). Mays et al. said there is admixture between filholi

and chrysocome, but Frugone et al. said they found none and argue that

the Mays et al.'s dataset was underpowered and could not evaluate species

boundaries. So while species concepts may be one aspect of the differing

conclusions, Frugone et al. 3 species and Mays et al. 2 species, there appears

to be differences in genetic data and analyses.

Mays, H. L., D. A. Oehler, K. W.

Morrison, A. E. Morales, A. Lycans, J. Perdue, et al. 2019. Phylogeography,

population structure, and species delimitation in rockhopper penguins (Eudyptes

chrysocome and Eudyptes moseleyi). The Journal of Heredity,

110(7):801–817. https://doi.org/10.1093/ jhered/esz051”

Comments

from Lane:

“NO, as per the comments by other committee members above.”