Proposal (1003x) to South

American Classification Committee

Species limits in the Myioborus

melanocephalus complex, revisited.

As

originally presented, this proposal (see below) did not pass, but it was

suggested that I present a revised version with more details on specific parts

of the proposal, progressing from north to south.

A.

Continue

to recognize M. albifrons as a species distinct from the rest of the

taxa related to the hybrid zone. The alternative would be effectively lumping

all of the complex into a single species ornatus, which has priority (a

possible option suggested by two members of SACC). However, no evidence of

hybrids between albifrons and ornatus exists; moreover, recent

eBird records of albifrons from the Tamá area on the border between

Colombia and Venezuela effectively establish parapatry between albifrons

and ornatus which would render untenable lumping them. Hence, I

recommend NO for this option.

B.

Recognize

M. chrysops as a distinct species from M. ornatus. The original

proposal failed to pass principally because of doubts regarding this split.

However, it was handicapped by the rather poor illustration of chrysops and

the lack of a good illustration of M. o. ornatus. Here are two photos

that I think represent these taxa more clearly:

M. o. ornatus:

M. chrysops:

Both taxa show a

generally similar pattern of brightly colored faces that present strong

contrasts with the dark irides, and with black napes, set off from dark gray

backs and wings. In both, note a fine white line in the black of the side of

the neck, approximately coinciding with the lower posterior border of the

auriculars. These patterns occur throughout the respective distributions

of each taxon. The principal difference between them is in coloration of the

face: glossy white in ornatus vs. glossy orange-yellow in chrysops. The

color of the underparts of ornatus is bright yellow, as are the forehead

and crown; chrysops is a more orange-yellow below and has a notably

different distribution of colors on the head, with the orange forehead much

more prominent and extending back over most of the orange-yellow crown. The current distributions of the two do not

overlap: chrysops occurs widely in the Central Andes, wherever the

elevation extends well above the 2000 m ridgeline – essentially an archipelago

of high Andean islands – and more locally in the Western Andes, where such

islands are much fewer and more isolated. Note that the isolated population of chrysops

where the Eastern Andes unite with the Central Andes is isolated by ca. 100

km from the southernmost limit of ornatus and is ca. 50 km east of the

hybrid zone between chrysops and the melanocephalus group. With

the current global warming, the geographic separation of chrysops and ornatus

can only increase, s.s.as the white postauricular line) do not represent

current or recent hybridization but more likely, the retention from a

considerably earlier common ancestor. To summarize:

The hybrid zone in the melanocephalus complex is strictly

with chrysops: ornatus is not directly involved. It thus more

clearly expresses the established precedent that the hybridization is occurring

between two full species. The distributions of ornatus s.s. and chrysops

are separated completely by at least 100 km of unsuitable habitat and no

hybrids between them are known. Their plumages differ strikingly in the head

region, of a magnitude similar to those distinguishing many other species of Myioborus;

plumage similarities between them are not evidence of current or recent

hybridization but retention of more ancestral characters. Perhaps pertinent

here is that the phenotypic differences in color and pattern between ornatus

s.s. and chrysops are if anything greater than the differences

between ornatus s.s. and albifrons, which appear to be parapatric

species.

Points in favor of a NO: The shallow

divergence in mitochondrial genetics between both species, although this could

be invoked for the complex generally, including M. albiceps, which is a

close sister to the remaining members, but which is apparently parapatric with M.

o. ornatus. The lack of direct evidence that the latter could interbreed

with chrysops were they to enter into contact is a piece of the puzzle missing, given their

disjunct distributions of some antiquity and is thus impossible to resolve. A

NO vote here would imply that the entire complex represents a single species

and consequently, the hybridization event occurs between subspecies of a

phenotypically extraordinarily diverse species.

My personal opinion

here favors a YES.

C.

Suppress

the name ruficoronatus due to the hybrid nature of its type, thus

rendering this name inapplicable to any described taxon. This should be an

undisputed YES given its clear genetic identity and distribution.

D.

Select

bairdi as the second parental species involved in the hybridization,

reflecting its adjacent distribution, its stable phenotype through central and southwestern Ecuador and the

compatibility of its phenotype for integration with the hybrid zone. This should

be an easy YES: no other taxon unites all of its qualifications.

E. Recognize griseonuchus

as a separate species from bairdi. At its southern limit around the

Ecuador-Peru boundary, bairdi meets griseonuchus, a poorly known

taxon that is phenotypically most similar to bairdi but the two are

reciprocally diagnosable. The current treatment appears to favor treatment of griseonuchus

as a subspecies of bairdi, but apparently there is no evidence of

hybridization between them, but only further collections and observations can

fully resolve its status as a subspecies or separate species.

I

lean toward a YES here, but tentatively, pending more data from the potential

zone of contact between them.

F.

Split

the remaining southern members of the complex as a separate species, M.

melanocephalus. This reflects the fact that the three included species have

black crowns, and zoogeographically, all occur east of the río Marañón valley

whereas bairdi and griseonuchus occur to the west; this low,

relatively dry valley is well recognized as a major barrier for the

distributions of taxa of the wet highland forests of opposite sides of the

valley. This decision should logically be YES.

G.

Continue

to recognize the currently known subspecies within M. melanocephalus. Its

three subspecies are distributed sequentially from northwest to southeast,

collectively ranging from northern Peru south to central Bolivia: malaris,

melanocephalus and bolivianus. Cuervo and Céspedes presented brief

descriptions, but emphasize that their respective distributional limits are

poorly documented, and the genetic characterizations are relatively incomplete;

clearly this group merits further study, but for the present they considered it

best to continue recognizing all three as described. I recommend a YES here.

Note from Remsen: At Dan Lane’s

suggestion, here are the published trees for Myioborus in case they are

helpful. Both are based on mtDNA

sequence data:

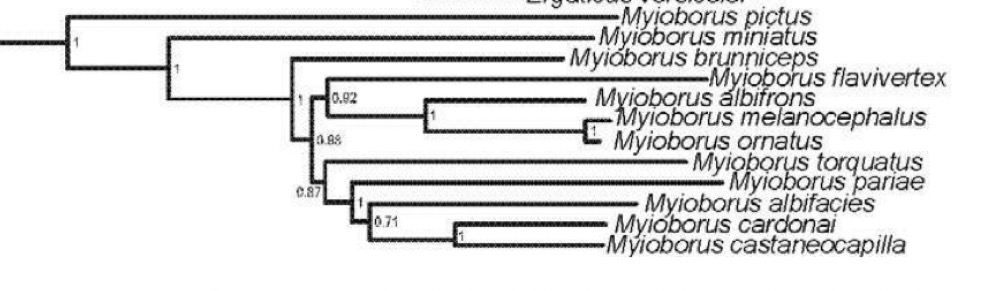

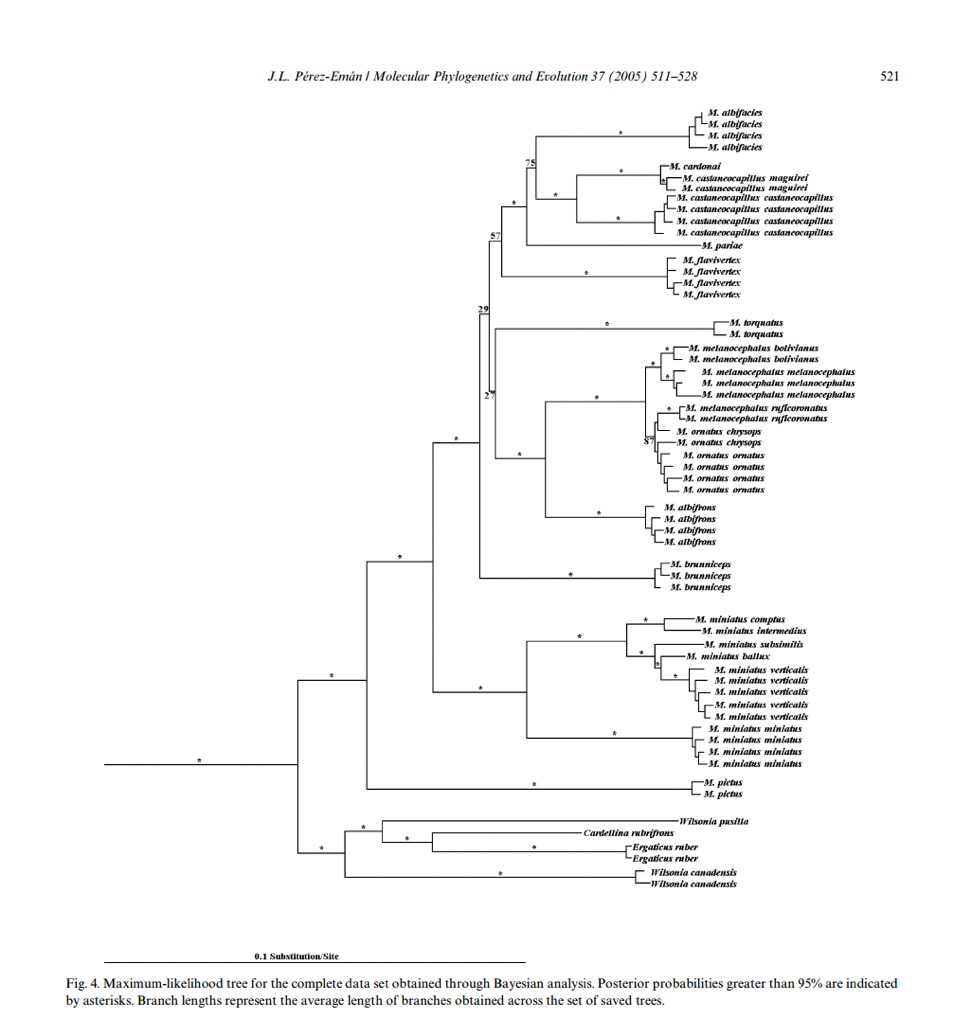

Lovette et al. (2010; MPE):

Pérez-Emán (2005; MPE):

Gary Stiles, September 2024

Voting chart: https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart968-1043.htm

Comments

from Zimmer:

“

“A.

I am a little confused by how this one is stated in the Proposal. It begins, by saying “Continue to recognize M.

albifrons as a species distinct from the rest of the taxa related to the

hybrid zone.” I would vote YES to

that for the reasons stated by Gary in the sentences that follow (e.g. the

alternative would be lumping all of the complex into a single species ornatus…

but there is no evidence of hybrids between albifrons and ornatus…and

eBird records effectively establish parapatry between albifrons and ornatus,

which “would render untenable lumping them”), but then, he says “Hence, I

recommend NO for this option.” It seems

to me that Gary is recommending NO to the option of lumping all taxa in the

complex into a single species, ornatus, to which I would also vote NO,

but the initial question was whether to continue to recognize albifrons

as a distinct species, to which I would reiterate my YES vote. Or am I missing something here?

“B. Recognize M.

chrysops as a distinct species from M. ornatus. I’m persuaded by the clarification presented

in the revised proposal, so a YES for me on this one.

“C.

Suppress the name ruficoronatus due to the hybrid nature of its

type. This would seem to demand an

obvious YES.

“D.

Select bairdi as the second parental species involved in the

hybridization. Another obvious YES.

“E.

Recognize griseonuchus as a separate species from bairdi. I’m uncommitted on this one. I think I would need more information to pull

the trigger on splitting these, so I lean toward a NO for now vote. The same logic that calls for treating the

three black-crowned taxa that occur east of the rio Marañón valley as a single

polytypic species (see Part F), would seem to argue for treating rufous-crowned

bairdi and griseonuchus from west of the Marañón as a single

polytypic species, rather than as two distinct species that are similar but

diagnosable.

“F.

Split the remaining southern members of the complex as a separate species, M.

melanocephalus. YES.

“G.

Continue to recognize the currently known subspecies within M.

melanocephalus. YES.

“What

I don’t see here, is a sub-part of the Proposal that explicitly addresses the

question of bairdi versus chrysops, given the broad hybrid zone,

with these two as the sole recognized parental types. If we are treating them as a single species,

and, if griseonuchus is treated as a subspecies of bairdi, then,

by my count, my votes would support recognition of 4 species: albifrons, ornatus, chrysops (including

bairdi and griseonuchus), and melanocephalus (including 3

sspp), which, I believe, is what both Mark and Dan suggested as an alternative

in the original Proposal. That would be

my leaning too, for 4 species.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“Based on the logic presented in the reappraisals above, recognizing four

species seems reasonable:

“1. Myioborus

albifrons: Phylogenetically distinct (long mitochondrial DNA branch in

Lovette et al, 2010 and Pérez-Emán 2025 papers) and phenotypically diagnosable.

2. Myioborus ornatus:

Not really part of the hybridization issue (since the hybridizing forms are chrysops

and bairdi). Also, phenotypically diagnosable and certainly does not

hybridize with neither albifrons (according to information provided by

Gary) nor chrysops.

3. Myioborus

chrysops: Includes chrysops, bairdi, and griseonuchus until

the hybridization zone is better understood with nuclear data. The geographic

continuity among these forms suggests a fluid entity composed of three

subspecies.

4. Myioborus

melanocephalus: Encompasses would include malaris, melanocephalus,

and bolivianus. According to Céspedes-Arias et al (2021) these three

forms share a fairly connected mitochondrial DNA haplotype network.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“YES to ABCDE - all the splits. Only one suggests very restricted gene flow

(which in relation to the broad expanses in the distributions of each showing

none, suggests menor preocupatión). Should any additional exchanges be

discovered, the zone of hybridization will almost surely be very narrow. An excellent study.”

Comments

from Areta:

“I developed the logic of my arguments before, and I still stand by them. I

find the proposed voting issues and sequence to be convoluted and unnecessarily

complicated. I think that the most

reasonable course of action based on current evidence is to recognize three

species largely following a N-S replacement: M. albifrons, M. ornatus,

and M. melanocephalus. Vocal and

genomic data will surely provide a richer perspective, and while I do not claim

that the 3-species solution is definitive, it is the one I see as currently

more defensible when integrating genetic patterns of differentiation, phenotype

(plumage and vocalizations), and hybrid zones:

A.

Myioborus albifrons: YES,

very distinct and parapatric to ornatus

without known hybrids. I do not agree with Gary´s assessment indicating that

"the phenotypic differences in color and pattern between ornatus s.s. and

chrysops are if anything greater than the differences between ornatus

s.s. and albifrons". Instead, I think that albifrons is very different from ornatus, while ornatus

and chrysops are very similar

(compare the photograph below to those of ornatus

and chrysops that Gary shared).

https://macaulaylibrary.org/photo/88090771

B.

Myioborus chrysops: NO. Include

the chrysops complex (chrysops,

bairdi, and griseonuchus) together with ornatus which has priority.

B.

Addendum. Myioborus ornatus: YES,

including chrysops, bairdi, and griseonuchus given the

geographically widespread and rampant hybridization, and also of course ornatus (given the broad similarity in

plumage and vocalizations to the chrysops

complex as argued previously in my first vote). As mentioned in point 1, ornatus is just slightly different from chrysops (slightly darker yellow, with

reduced white on the face), and under the BSC/Recognition Concept I don´t think

they will keep their integrity: I predict rampant hybridization would happen if

they ever meet, even if their current ranges are now allopatric.

C.

YES. ruficoronatus represents a hybrid phenotype and I don´t see a need

to keep recognizing it.

D.

NO. It is clear that bairdi

is the second taxon involved in the hybrid zone, but given the geographic

breadth and frequency of hybridization, I don´t support recognizing bairdi

as a full species. Instead, I consider it a subspecies of M. ornatus (see B and B addendum) that hybridizes with the

subspecies chrysops.

E.

NO. I don´t see strong evidence to

recognize this taxon as a full species (see F).

F.

Myioborus melanocephalus: YES

(although there is room for debate), including malaris, melanocephalus,

and bolivianus. Note that, as discussed before, the situation across the

Marañón separating griseonuchus and malaris is not clearcut based on genetic

information, and vocally the melanocephalus

group is pretty much like ornatus

(including the chrysops group). I

vote to retain melanocephalus for the

time being, but I would not be averse to lumping it with ornatus if genomic+vocal evidence arise supporting such a lump.

G.

YES, as in F.

Comments

from Jorge Pérez-Emán (voting for Del-Rio): “This proposal to define species

limits in one monophyletic group of the genus Myioborus is full of complexity. The evolutionary history and

differentiation of the northern/central high Andean species complex (albifrons, ornatus and melanocephalus)

is a fascinating system to study evolutionary processes associated with the

generation of diversity. Earlier studies provided a phylogenetic hypothesis for

the group and suggested potential paraphyly for melanocephalus in relation to ornatus

(Pérez-Emán 2005, Lovette et al.

2010). This finding associated with the increasing information of observations

of phenotypically intermediate birds in southern Colombia – northern Ecuador

led to the study of Céspedes-Arias et al.

(2021) that described and analyzed the complex system of hybridization between

these taxa. Cuervo and Céspedes (2023) followed up with a revision of the

taxonomy of the group and provided with different proposals congruent with

findings of this last study. These studies underscore a complex evolutionary

dynamic that generates lots of questions, but we are still short of having

clear answers. Consequently, when I see a proposal (and subsequent

responses/votes) suggesting one (just as the baseline), two, three, four, five

and six species (from a universe of nine voters), it suggests that uncertainty

is larger than the information required to make clear and stable changes to the

current taxonomy of the group. I will share my thoughts (and available data)

for each of the proposal optional splits and then summarize/ponder the

different scenarios for number of species suggested for this group of Myioborus in light of what we know right

now.

“A. Myioborus albifrons, a separate species?

This is a taxon restricted to the Venezuelan Andes (Tachira, Merida and

Trujillo) and it is allopatric in

its distribution in relation to other members of the group (specifically, M. o. ornatus), with no records of

hybridization between these taxa. These taxa are potentially isolated by the Táchira

Depression, and arid valley separating the Venezuelan Andes from the Tama

mountains from where, as far as I know, there are no records of albifrons. Phenotypically it is

characterized by a crown black with a rufous patch with several feathers tipped

black and white forehead, supralorals and eyering, forming a “white spectacle”,

a plumage pattern not very different to that of melanocephalus populations north of the Marañon River (Figure 1).

Molecular studies suggest M. albifrons

is the sister taxon to the ornatus-melanocephalus

complex and diverge from them around 4% uncorrected sequence divergence in some

mtDNA genes, with a small intraspecific genetic variation (Pérez-Emán 2005).

Such phylogenetic relationship was supported by increasing number of both

mitochondrial and nuclear genes (Lovette et

al. 2010) and a recent mitogenomic analysis (Zhang et al. 2025, which

unfortunately sampled ornatus from

toepads, and their nuclear results were messy in this case). In summary, I think

all data currently available support species status for this taxon.

“Figure 1. Plumage color variation in M. albifrons and M. melanocephalus north of the Marañon River. Notice the

similarities in plumage coloration pattern between both species, the intensity

variation in the ventral yellow coloration (in all taxa), and the absence of

black nape and variation in size and color of crown patches throughout the

distribution of melanocephalus.

Top row: M. albifrons (Venezuela) from

left to right: Táchira, https://ebird.org/checklist/S220813847; Mérida,

https://ebird.org/checklist/S162418134; Mérida, https://ebird.org/checklist/S220813847.

Middle row: M. melanocephalus “ruficoronatus” (bairdi, Ecuador), from left to right, Pichincha,

https://ebird.org/checklist/S162780652; Tungurahua,

https://ebird.org/checklist/S138756945; Tungurahua,

https://ebird.org/checklist/S160083246; Azuay, https://ebird.org/checklist/S113062604; Loja, https://ebird.org/checklist/S152346432;

Third row: Myioborus melanocephalus

griseonuchus (Peru), from left to right: Piura,

https://ebird.org/checklist/S124270377; Cajamarca,

https://ebird.org/checklist/S61949069; Cajamarca,

https://ebird.org/checklist/S65191736; Cajamarca,

https://ebird.org/checklist/S60936330;

“B. Myioborus ornatus: two species (ornatus and chrysops)? Previously considered geographical variation of M. ornatus, labeled subspecifically,

these taxa were recently proposed to represent different species by del Hoyo

and Collar (2016), using the Tobias et al.

(2010) phenotypic criteria for species delimitation. They justified such split

based on differences in the white vs. yellow around the eye, amount of yellow

and its intensity on the forehead and ventral side, respectively, and slight

differences in the length of vocalizations. Additionally, this proposal

includes the geographical isolation of o.

ornatus and o. chrysops and the

isolation of o. ornatus from the

hybrid zone between o. chrysops and melanocephalus. It is emphasized that

the hybrid zone is strictly with o.

chrysops and not o. ornatus and

that no hybrids between these taxa are known. It adds that phenotypic

differences between o. ornatus and o. chrysops are about the same or larger

than between o. ornatus and albifrons.

“Although all these points are potential good

reasons to consider each taxon as separate species, it is important to consider

phenotypic variation, mostly plumage here, but also vocalizations. As Nacho

indicated previously, vocalizations are very similar in all this group (even albifrons) and slight differences in

length of the song, shorter or longer than 5s (even considered minor

differences by del Hoyo and Collar 2016) could also be the result of sampling

size and geographical biases (which I cannot confirm because I did not find the

data supporting these differences). On the other hand, pictures of these taxa

taken throughout their distribution (Figure 2) show an amount of plumage color

variation that suggest plumage differences are not clear-cut, even though we

could find good examples of ornatus

and chrysops in the northern portion

of each taxon ranges (but no rigorous data available at this moment). Moreover,

although I could not find on my files the complete specimen information, many

years ago I found at the Instituto de Ciencias Naturales de Bogotá, Colombia

(ICN), one specimen of ornatus

collected by Bernal and Olivares (potentially from the 60’s?), from Fusagasuga,

Cundinamarca, that approaches the plumage pattern of “typical” o. chrysops, side by side with other

individual “typical” o. ornatus from

the same locality (Figure 3). Although these pictures/specimens do not

represent the common pattern throughout the distribution of each taxon, they

show that there is variation in their plumage, that is “possible” to go from

one plumage type to the other, and that individual variation could even be

larger than among locality variation (see Céspedes-Arias et al. 2021).

“Figure 2. Plumage color (and pattern)

variation in Myioborus ornatus from

Colombia. See variation in ventral coloration (bright yellow to orange in both

taxa) and the amount of white in the face of o. ornatus (even almost disappearing in one individual from Bogotá).

Notice that variation is not geographically structured as some of the

differences are found at the same or nearby localities.

Top row: Myioborus ornatus ornatus

from left to right: Bogotá, https://ebird.org/checklist/S38604592; PN Chicaque,

Cundinamarca, https://ebird.org/checklist/S202692769; Bogotá,

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/192970091; Bogotá, https://ebird.org/checklist/S103828264.

Bottom row: Myioborus ornatus chrysops,

from left to right: Antioquia, https://ebird.org/checklist/S124051776;

Antioquia, https://ebird.org/checklist/S121272164; Antioquia,

https://ebird.org/checklist/S100185842.

“Figure 3. Pictures of Myioborus ornatus ornatus from Fusagasuga, Cundinamarca, Colombia.

The specimens are from the collection of the Instituto de Ciencias Naturales (ICN), Bogotá,

Colombia (numbers 1425 and 5310). It is far from a good picture, but it shows

within locality variation in face pattern/color of this taxon in the range of o. ornatus. The specimen with less white

(#5310) was collected by Olivares and Bernal.

“We also need to focus on the data shown by

Céspedes-Arias et al. (2021) in

relation to the hybridization pattern between these taxa. Phenotypic variation

is huge and clearly suggests a hybrid zone that includes southern Colombian and

northern Ecuador. However, the hybrid zone was described based on the

phenotypic characters, but the other part of the story is that there were no

fixed haplotypes at either end of the hybrid zone that could be used to

characterize the parental populations. I think information from phenotypic

characters in these hybrid zones is of great importance (as it is also the

potential subject of selection), but it is also important to consider that the

hybrid zone could be different if we focus on the genetic data. Extensive

sampling of mtDNA (ND2 gene) variation shows that the most common haplotype is

found throughout the complete distribution of both o. ornatus and o. chrysops

and reaches Tungurahua, Ecuador, in the range of melanocephalus. Moreover, out of 27 o. ornatus samples, 14 of them shared haplotypes with hybrids.

Similarly, 10 out of 15 samples of o.

chrysops were characterized by the hybrid haplotypes; and we are referring

to “phenotypically pure” diagnosed taxa. We could interpret these findings as a

really young divergence between these taxa (recent gene flow between them), and

that both ornatus taxa are involved

in the hybrid zone with the presence of genotypic hybrids. Lastly, but not less

important, Céspedes-Arias et al.

(2021) indicated the presence of concealed black feathers with rufous base far

from the hybrid zone in both o. ornatus

and o. chrysops.

“In summary, given the clear similarity between

both taxa plumage pattern and coloration, as well as vocalizations, and the

fact that they are genetically homogeneous throughout their distribution,

including the hybrid zone, the evidence supports more a scenario of a single

species with geographical variation rather than separate species. However, how

could such phenotypic differences exist in the presence of such similarity at

the genetic level? more of that below but, for now, my take would be of one species

including both taxa.

“C. Myioborus

melanocephalus ruficoronatus is not a valid taxon. The evidence presented

by Cuervo and Céspedes (2023) is thorough and definitely supports the proposal

of considering ruficoronatus a

non-valid taxon and assign the populations of birds with such similar phenotype

to bairdi. I indicate similar

phenotype because the ruficoronatus

type has similar plumage coloration to hybrids in the region, but not the same

as the population we historically have named ruficoronatus. Consequently, the type is proposed to be a hybrid

and the locality type reassigned to Pasto (no evidence of Cali as collection

site). The history of several of these old types is not always simple but

rather convoluted, and I think the work by Cuervo and Céspedes (2023) is

thorough and complete as it could be with the evidence on hand. I just want to

emphasize, due to potential misinterpretation from the proposal, that there are

no genetic data from the type, and its distribution is inferred based on

coloration patterns from the hybrid zone by Céspedes-Arias et al. (2021).

“D

and E. Select (and recognize) M. m.

bairdi as the species (taxon) hybridizing with ornatus and include griseonuchus

in this species (or recognize it as a different species) I include both

sections of the proposal here as they are really interconnected. If we accept ruficoronatus should be replaced by bairdi as the appropriate name for the

adjacent form to ornatus (o. chrysops as in the proposal),

hybridizing with it, then it follows bairdi

should be considered the second parental species. However, the proposal

includes (from section D and E) that bairdi

is characterized by a stable phenotype throughout central and southwestern

Ecuador, that the southern limit of griseonuchus

is the Ecuador-Peru boundary, and that both forms are reciprocally diagnosable

with no evidence of hybridization between them. A final note to this section is

the most undebatable fact: we need appropriate morphological and molecular

sampling, both in size and geographical coverage, to have a clear answer to the

question about the specific/subspecific status of these forms.

“First,

I think the phenotype of these forms from central Ecuador to northern Peru is

not stable but variable. You can see from a cursory view of different pictures

from their geographical range (Figure 1 below) that there are not clear cut

differences in the extent and coloration of the crown patch and, most

importantly, in the presence or extension of the black nape behind the crown

patch. In fact, Céspedes-Arias et al.

(2021) highlighted the presence of individuals, in their dataset, that could be

considered one form or the other, suggesting that the geographical limits

between both forms are not clear (if in fact there is one limit) and that these

forms, as actually defined, are not clearly diagnosable. Such difficulty to

separate individuals from these taxa were also faced by Chapman (1927) and

Zimmer (1949), but the easier diagnosis as we move toward northern Peru

convinced them to describe and keep this form as a valid subspecies. The

molecular data further complicate things. There are shared haplotypes between

both bairdi and griseonuchus, and

the geographical distribution of those haplotypes is important to consider. The

type locality of bairdi is Cicalpa

Viejo, in Chimborazo, Ecuador, just south of Tungurahua. On the east and

southeast, you can find Sangay National Park and the Cordillera of Cutucú, in

the Morona-Santiago province (localities sampled by Céspedes-Arias et al. 2021). In Tungurahua, the last

locality considered for the hybrid zone, as representative of the parental

phenotype in the south, all haplotypes were either shared with hybrids or

closely related to the ornatus-melanocephalus

haplotype group. From here to the boundary between Ecuador and Peru, bairdi phenotypes south of the type

locality were either genetically closer to ornatus-melanocephalus

or griseonuchus, or hybrid

haplotypes. Similarly, phenotypes in the bairdi

potential range but with some phenotypical similarities to griseonuchus, were closer either to the ornatus-melanocephalus or to the griseonuchus group. This pattern is specifically relevant in the

Morona-Santiago localities where haplotypes shared with griseonuchus were geographically north of those shared with the ornatus-melanocephalus group. Thus,

available data suggest an area of potential genetic exchange/mixture between

the north and the south, resulting in a potential “pure bairdi” geographical range unclear or potentially extremely small.

We could even argue, based on genetic similarities and north-south plumage

coloration pattern, that griseonuchus

might better reflect the parental phenotype from the hybrid zone (in fact, some

haplotypes of ruficoronatus and

hybrids are more similar to the griseonuchus

haplotype cluster than to the ornatus-melanocephalus

group), but it is just an alternative hypothesis.

“In

summary, these taxa are not clearly diagnosable to me and recognize even their

subspecific status might require a thorough morphological study.

“F.

Recognize black crown phenotypes, south of the Marañon River, as melanocephalus This section recognizes

phenotypic differences in melanocephalus

north and south of the Marañon River (chestnut vs. black crown, respectively),

in correlation with the potential geographical/ecological barrier represented

by this river and associated with many bird Andean splits. The issue here are

the haplotypes found in the only malaris

population studied (Amazonas Department, Peru), which are shared both with griseonuchus and melanocephalus/bolivianus.

Molecular divergence from the mtDNA (ND2) is just 0.5%, and a major difference between

malaris and melanocephalus/bolivianus

(malar stripe connecting the lores and auriculars and interrupting the yellow

eyering) is shared between griseonuchus

and malaris (Zimmer 1949). This same

author found two individuals (of malaris)

with traces of brown on the base of crown feathers, suggesting intermediacy

between these forms. Something interesting I noticed, looking at pictures from

the northern hybrid zone, is that some hybrid birds approach the black crown

phenotype of the south, suggesting it might not take much to switch from one

phenotype to the other (Figure 4 below).

“Figure 4. Variation of plumage coloration in Myioborus melanocephalus south of the

Marañon River (Peru and Bolivia). Ventral coloration and face patterns show

variation throughout the distribution of these three taxa. The first picture

represents a hybrid bird from Putumayo, Colombia, in which the crown is almost

black, approaching pattern in this group of melanocephalus.

Top row: from left to right, ornatus x melanocephalus, Putumayo, Colombia, https://ebird.org/checklist/S30754385; malaris: Amazonas,

https://ebird.org/checklist/S97463664; Amazonas, https://ebird.org/checklist/S194175525; San Martín, https://ebird.org/checklist/S63751287; melanocephalus: Huánuco, https://ebird.org/checklist/S63850047;

Middle row: from left to right, melanocephalus,

Pasco, https://ebird.org/checklist/S66189166; Pasco,

https://ebird.org/checklist/S215302743; Junin,

http://ebird.org/checklist/S214612265; bolivianus:

Cuzco, https://ebird.org/checklist/S112334054; Puno, https://ebird.org/checklist/S144178912;

Bottom row: from left to right, Cochabamba, https://ebird.org/checklist/S65135514;

Cochabamba, https://ebird.org/checklist/S155269136; Cochabamba, https://ebird.org/checklist/S160415431; Santa Cruz, https://ebird.org/checklist/S198792492”

“G.

Recognize current geographical variation in melanocephalus,

including malaris, melanocephalus and bolivianus. As indicated in this section, these three taxa run

north to south, showing continuous or discrete variation in the characters

defining them, making it difficult to discern geographical limits among them

(Figure 4). Also important to state is that similar haplotypes at either side

of the Marañon River might indicate potential introgression or recent gene flow

suggesting malaris could be

genealogically closer to northern forms (bairdi

and griseonuchus) than to southern

ones (if so, we will need to ask ourselves what the factors are associated with

differences in plumage coloration in these birds). The haplotype network shows

a melanocephalus/bolivianus more cohesive group in comparison to the relationships

of the malaris haplotypes. It is

important to understand that although the Marañon River is an important barrier

for Andean birds, many lineage breaks do not correspond to this barrier

(phenotypically or genetically), and we can have no breaks or finding them

further south (San Martín, Huánuco, Pasco), as shown in phylogeographical

hypothesis for several Andean taxa across the Marañón River barrier (e.g., Mionectes striaticollis, Tangara vassorii, Pyrrhomyias cinnamomeus; Cuervo 2013).

“In summary, regarding the last two sections,

we need thorough morphological studies of variation in the black crown melanocephalus, as well as a better

molecular evaluation of the region in which the crown changes coloration (the

major difference among these taxa). I do not see further splits within melanocephalus, but the case for malaris

is still contentious, which could impact decisions regarding the recognition of

different species north and south of the Marañón River for melanocephalus.

“How

many species in the albifrons-ornatus-melanocephalus

species complex?

“From the evidence available I think M. albifrons is the clearest candidate

for species status. Data suggest this taxon to be the sister species to the

rest of the complex, it seems to be homogeneous both phenotypically and

genetically, and it appears to be isolated from the rest of the complex by the apparent

stronger geographical barrier in the history of this specific group. Its

phenotypic similarity to rufous-crown melanocephalus

might make one to speculate on the potential ancestral phenotype, which could

be present in the northern Andes at least 2-3 Mya, based on the stem age of

this group.

“The case for the taxa north of the

Marañon River is the most complex to understand with the data on hand. We have

a phenotypic hybrid zone that includes a rufous-crown melanocephalus with o.

chrysops, but the mtDNA data show that genotypically the hybrid zone

includes the northern extremes of both ornatus

phenotypes and go farther south of the bairdi

type locality. In fact, Céspedes-Arias et

al. (2021) found phenotypic hybrids farther south of the hybrid zone (but

not as intermediate as you can find in the middle of it). The reality is that

there are still many questions waiting for answers: is the hybrid zone primary

(selective divergence due to environmental conditions or other selective agent)

or secondary (contact between two previously isolated species)?; is it

asymmetric (one taxa displacing the other)? is it advancing or controlled by

selection? We need genomic data, and we could ask how such data could impact

our decisions here. It could indicate that genomic divergence is large among

the taxa involved in the hybrid zone and correlated with phenotypic

differences; if so, we could suggest secondary contact and potential

introgression or positive selection (e.g., selective sweep) of mtDNA, a pattern

misleading the interpretation of the evolutionary history of the complex. On

the other hand, it could show the same mtDNA pattern, suggesting recent

expansion and diversification (as the high haplotype diversity and low

nucleotide diversity could indicate) and a lack of reproductive isolation

between these taxa. Alternatively, we could find lack of general genome

divergence except for few genes that could be involved in plumage color/pattern

differences, suggesting these traits could be under selection. Understanding

these processes is important because it could suggest the hybrid zone is

advancing and homogenizing all populations, or, for example, there is selection

against hybrids and assortative mating occurs and prevents the hybrid zone for

advancing. For me, knowing these patterns/processes will provide the clues to

suggest there are one or several species involved here.

“The case for the black-crown melanocephalus south of the Marañon

River is perhaps less complicated, but the truth is that we know less here.

Morphological variation is far from clear (similar to the case of the

rufous-crown melanocephalus), and we

need thorough studies of geographical variation, both in the phenotype and

genotype. There has been consensus that the three forms south of the river

should be kept together in one species unless future data suggest otherwise.

What is contentious is the case malaris,

as its haplotypes are shared both south and north of the river. I would like to

include an example from the same genus to think about it. In a previous study, M. castaneocapillus was found to be

paraphyletic in relation to M. cardonai,

two species from the Pantepui Region (Pérez-Emán 2005). One subspecies of castaneocapillus was found sister to cardonai, a surprising result as we

thought both cardonai and albifacies were sister taxa (more

similar phenotypically). One possibility would be this pattern reflects

accurate phylogenetic relationships leading to recognize more species (many of

these taxa are geographically isolated) or to invoke introgression (due to some

phenotypic similarities with one unsampled populations of castaneocapillus). A recent genomic study (Zhao et al. 2025) found cardonai sister to albifacies with high support, contrary to our previous study, which

was also backed up with high support (mtDNA). Why do I mention this? Different

strongly supported data could tell us different stories. Available data from malaris and our logical perception that

different phenotypes (rufous vs. black crowns) should be different, suggest the

potential for mtDNA introgression in the range of malaris or incomplete lineage sorting from a recent divergence

potentially correlated with the geographical barrier represented by the Marañon

River. If we split now, what if genomic data suggest both rufous and black

crowns melanocephalus are closer to

each other and both to ornatus? It

could drastically change our perception of species limits here and will promote

further discussion.

“In

summary, I think each of the potential scenarios to consider from this proposal

regarding the number of species included in this complex, from 2 to 6 species,

has merits and are based on different aspects of the data we have available

right now. However, as Céspedes-Arias et al. (2021) concluded, their study

“..provides a starting point for additional research on the dynamics of this Myioborus hybrid zone”. As such, more

data are required to safely make taxonomic moves that are stable on time and

adjust to the established working criteria (species concepts). Time and new

data will get us closer to understand the evolutionary dynamics of this group

and support (or potentially reject) the claims for each of the potential

splitting scenarios. For me, if we are going to make a change to the current

taxonomy, I will stand for a conservative one: two species, M. albifrons and the rest (ornatus, I believe, for priority), with

the reasons clearly stated before. Any move, even with their merits, includes a

certain amount of uncertainty that invites for more changes in the future. The

good news is that Laura (Céspedes-Arias) is currently working on the genomic

characterization of this complex and will likely place us in a more suitable

position to make data supported taxonomic decisions.

“References:

· Céspedes-Arias, L et

al. 2021. Extensive hybridization between two Andean warbler species with

shallow genetic divergence. Ornithology 138: 1-28.

· Chapman, FM. 1927.

Descriptions of new birds from northwestern Peru and western Colombia. American

Museum Novitates 250: 1-7.

· Cuervo, AM. 2013.

Evolutionary assembly of the Neotropical montane avifauna. LSU Doctoral

Dissertations, 275.

· Cuervo, AM & L

Céspedes-Arias. 2023. The type of Setophaga ruficoronata is a hybrid:

implications for the taxonomy of Myioborus warblers. Zootaxa 5383:

476-490.

· del Hoyo, J & NJ

Collar. 2016. HBW and BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds

of the World. Volume 2: Passerines. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

· Lovette, IJ et al.

2010. A comprehensive multilocus phylogeny for the wood-warblers and a revised

classification of the Parulidae (Aves). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution

57: 753-770.

· Pérez-Emán, JL. 2005.

Molecular phylogenetics and biogeography of the Neotropical redstarts (Myioborus; Aves, Parulinae). Molecular

Phylogenetics and Evolution 37: 511-528.

· Tobias, JA et al. 2010. Quantitative criteria for

species delimitation. Ibis 152: 724-746.

· Zhao, M et al. 2025. A phylogenomic tree of

wood-warblers (Aves: Parulidae): Dealing with good, bad, and ugly samples.

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 202: 108235.

· Zimmer, JT. 1949.

Studies of Peruvian birds. No. 54. The families Catamblyrhynchidae and

Parulidae. American Museum Novitates 1428: 1-59.

Additional comments from Areta: “I agree with Jorge´s

in-depth analysis which has added key data and perspectives in an exemplary

analysis (¡gracias Jorgito!). We seem to be largely

aligned in how we see the case, and Jorge´s deep-dive into the case has shed

new light into this. SACC currently considers three species in the complex: albifrons,

ornatus, and melanocephalus. I have expressed my reservations on

whether the split between ornatus and melanocephalus across the

Marañón will hold once genomic and more morphological data are available, as

current data indicate some type of leakage over the valley (but we do not know

in detail what is going on here). Thus, I think that the conservative stance

here would be to keep recognizing three species (albifrons, ornatus,

and melanocephalus) instead of two (albifrons north of the

Táchira depression and ornatus everything south of the Táchira

depression). I am really eager to read Laura´s next work on the complex."

Comments from Robbins: “Impressive in-depth analysis by

Jorge! I think his conservative,

well-reasoned suggestion of recognizing two species, albifrons and ornatus

(apparently that has priority for this group of taxa), is the best course of

taxonomy at this point. Naturally, we

all look forward to Laura Céspedes-Arias genetic data that may provide further

clarification of this complex.

“Major kudos to Jorge for helping sort through things as they now

stand.”

Comments from Claramunt: “I vote conservatively, as the

new evidence does not challenge the current SACC taxonomy and the proposals for

alternative species limits are not backed by published evidence.

“A. YES. Continue

to recognize M. albifrons as a separate species.

“B. NO to

recognize M. chrysops as a distinct species from M. ornatus. It’s

an interesting possibility but there is no new data to support it.

“C. YES to

suppress the name ruficoronatus; eliminate it from being a valid

subspecies.

“D. YES but

not sure how this is pertinent to SACC.

“E. NO.

There is no new published evidence supporting species status for bairdi.

“F. YES to

continue recognizing the remaining southern members of the complex as a

separate species.

“G. NO. As

shown by Cuervo and Céspedes, subdivisions withing the southern group are not

well characterized. I think it’s better to recognize the groups as a single

taxon.”

Comments from Lane: “Thanks for the trees, although

they are "just" mtDNA, so taken with a pinch of salt. For example, I

am floored that M. torquatus is not sister to the remaining M.

melanocephalus/ornatus complex in the Lovette tree, as it certainly

has the voice and plumage for it! Happily, it seems to be sister in the Pérez-Emán

tree. Anyway, here are my votes:

“A) YES to

continuing to recognize M. albifrons as a species.

“B) NO. At

least in the Lovette tree, it appears as though chrysops and ornatus

are interdigitated (but see my comment about M. torquatus above with

respect to the branches on that tree!). Nevertheless, even if these taxa are

allopatric, they seem pretty close in many respects.

“C) YES to

suppressing ruficoronatus.

“D) YES to

recognizing the name bairdi.

“E) NO to

recognizing griseonuchus as a separate species.

“F) YES to

recognizing the birds south of the Maranon as M. melanocephalus, a

separate species from M. ornatus.

“G) A very

weak YES to continue recognizing the subspecies under melanocephalus.

These will likely prove to be clinal, and thus may have no real meaning, but

until that is shown, I am fine maintaining them as named taxa for now.”

Comments from Remsen: “I can’t add anything that hasn’t

already been said in the many good comments above. Thanks especially to Jorge for the helpful,

extensive comments. We currently do not

provide a classification at the subspecies level, but that will happen

eventually, so those parts of the proposal lay some groundwork for that.

“A. YES. No change to status quo warranted.

“B. NO. More data needed.

“C. YES.

“D. YES – insufficient data to make a change.

“E. NO - insufficient data to make a change.

“F. YES - insufficient data to make a change.

“G. YES. Any change is

premature without a quantitative analysis of geographic variation.”

________________________________________________________________________________________

Proposal (1003) to South American Classification Committee

Species limits the Myioborus melanocephalus

complex: Taxonomic options for resolving the classification of the species

forming an extensive hybrid zone between southern Colombia and northern

Ecuador, and related taxa

Antecedentes: Céspedes-Arias et al. (2021) described

in detail an extensive hybrid zone

between a northern taxon, Myioborus ornatus chrysops, and a southern

taxon (M. melanocephalus ruficoronatus (the northernmost subspecies of M.

melanocephalus). This hybrid zone is exceptionally long, covering ca. 200

km between southwestern Colombia and northwestern Ecuador and is apparently

stable (no “pure” parental phenotypes occurring within the central hybrid

zone). They found that the mitochondrial genetic differences along this zone

were extremely small but the phenotypic differences, particularly in plumages

of the head, were visually striking. Treating

the entire melanocephalus complex as a cline, apparent gene flow

along the occurs with only a distinct a break at the dry Marañon valley of Peru

(a well-known barrier separating highland wet-forest taxa on either side).

The taxonomy

underlying the aforementioned study was effectively relegated to the dustbin by

Cuervo & Céspedes-Arias (2023) when they examined the photographs, original

illustrations and description of the type specimen of ruficoronatus and

found that its plumage was identical to those of hybrid specimens from near the

midpoint of the hybrid zone, with its probable provenance from the area of

Pasto, Nariño, Colombia. Here is he

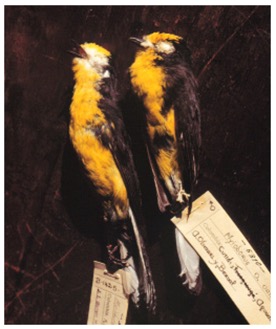

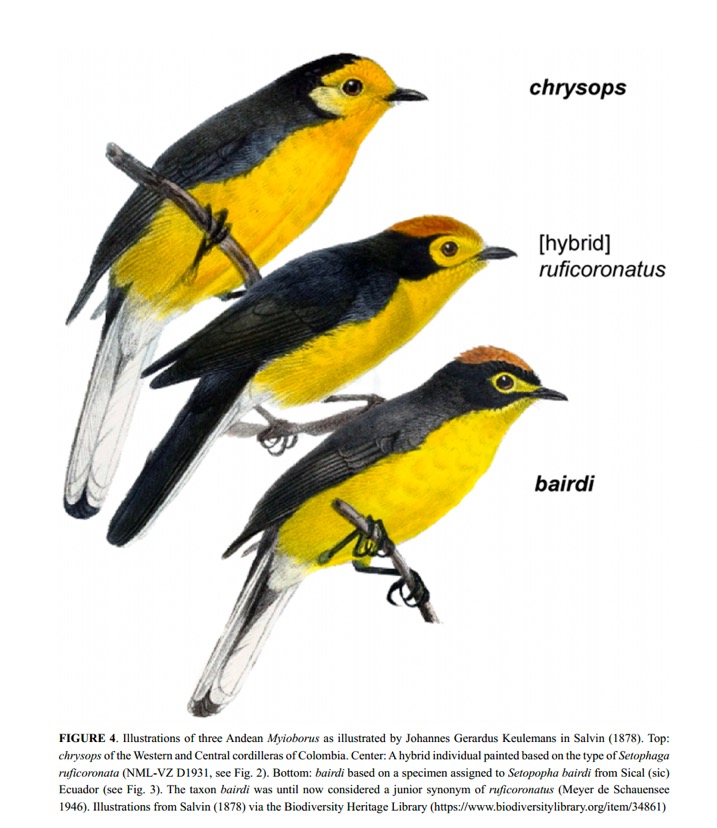

plate from Cuervo and Céspedes-Arias:

This effectively

excludes ruficoronatus as the name of any valid taxon, and

prompted a more far-reaching examination of other taxa, including their type

descriptions, photographs of same, and distributions, initially to find the

“pure” species-level taxon that would represent the southern parent of the

hybrid zone. For brevity here, I omit details of type descriptions and

photographs, for which see Cuervo & Céspedes-Arias (2023). The appropriate

southern parental taxon found was bairdi once the confusion regarding

its distribution and erroneous synonymization under ruficoronatus had

been cleared up. This taxon is found through central and southern Ecuador. They

then proceeded to examine the distributions, type specimens and distributions

of the other taxa of the clade that includes the hybrid zone, and including M.

albifrons of Venezuela, the sister and near outlier to this clade. North of

the hybrid zone, three taxa occur: M. o. ornatus of the Eastern

Andes and M. o. chrysops of the Central Andes of Colombia, as well as albifrons.

Proceeding south on the eastern slope of the Andes, the taxa include griseonucha

(currently considered a subspecies of bairdi), malaris,

melanocephalus and bolivianus (the last three considered subspecies

of melanocephalus). This chain of taxa is bisected by the dry

Marañón valley of eastern Peru. Of the aforementioned taxa, bairdi and

griseonucha occur to the north and west of this barrier, with the three

taxa of melanocephalus to the south and east.

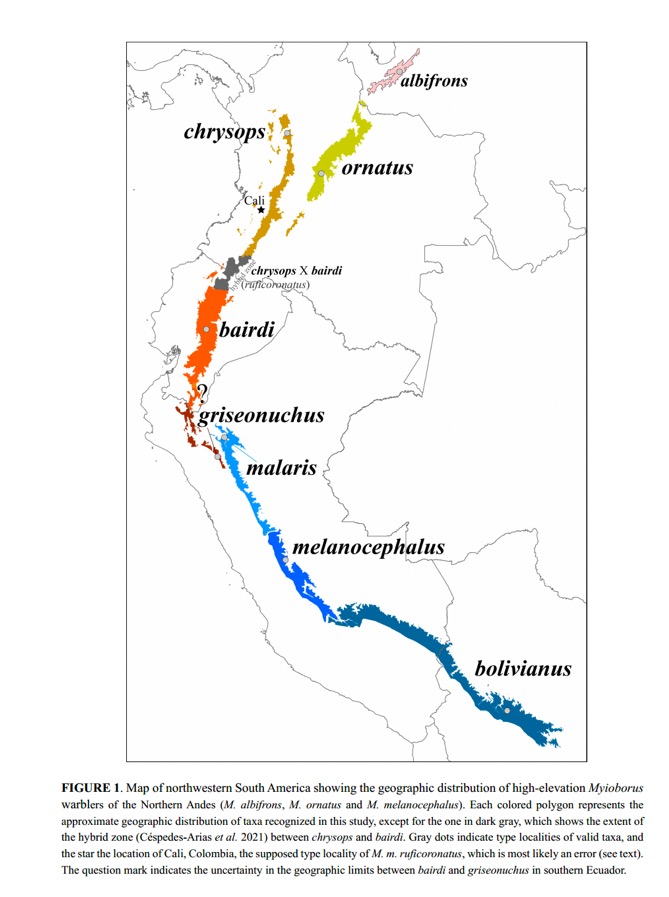

Here is the

distribution map from Cuervo & Céspedes-Arias (2023):

The authors found

that genetic variation over the entire complex permitted recognition of four

genetic clusters, largely correlated with geography and partly with phenotypic

patterns: 1) M. albifrons,

isolated from the remining taxa in the Venezuelan Andes; 2) M. melanocephalus

(including malaris and bolivianus), east and south of the

Marañón; 3) M. bairdi and griseonucha, north and west of

the Marañón, and 4) M. o. ornatus and M. o. chrysops, north of

the hybrid zone. Hybrid genotypes and phenotypes clustered with groups 3 and 4.

They then proposed three taxonomic hypotheses for the species represented among

these taxa:

A. Three species: M. albifrons, M. ornatus

(all of the taxa north of the Marañon and including the hybrid zone) and M.

melanocephalus, south of the Marañón. Thus, ornatus includes a variable

mixture of yellow- and white-faced and partly to entirely black to

rufous-crowned taxa; albifrons has a white eyering and forehead and

black crown, and melanocephalus includes all black-crowned taxa, and is

excluded from participation in the hybrid zone by the intervening,

rufous-crowned bairdi and griseonuchus. The species status of albifrons

is not affected; in fact, its distribution approaches rather closely to

nominate ornatus from the north, but no hybrids between the two are

known.

B. Five species: M. albifrons, ornatus,

chrysops, bairdi and melanocephalus. This option differs in

splitting chrysops and bairdi from ornatus. This is

advantageous in recognizing the hybrid zone as strictly between chrysops and

bairdi. Both melanocephalus s.s. and ornatus s.s. are

isolated from this zone: the former by bairdi (and griseonuchus)

on the opposite side of the Marañón valley, and ornatus from chrysops

by the wide Magdalena River valley. No phenotypic evidence of recent

hybridization between the latter two exists, and their similarity in

mitochondrial genetics possibly best indicates incomplete lineage sorting

during their separation. Moreover, the temperature increase due to ongoing

climate change further reduces probability of future genetic exchange between ornatus

and chrysops, and some checklists have in fact accorded

separate species status to each. Cuervo & Céspedes-Arias (2023)

favored this option.

C. Six species, by the additional separation of griseonuchus

from bairdi reflecting their phenotypic diagnosability and the

apparent absence of hybrid phenotypes between them. The problem here is that

very few specimens are available from the area of possible contact across the

border between Ecuador and Peru; further collecting and field observations are

needed to evaluate this possible split.

For the SACC, I

recommend voting YES for one of the above three options: if any one receives a

majority of votes, it passes; if no option passes, the voting could be repeated

after eliminating the option least voted.

A. Three species

B. Five species

C. Six species

Literature cited:

Céspedes-Arias, L. et

al. 2021. Extensive hybridization between two Andean warbler species with

shallow genetic divergence. Ornithology 138:1-28.

Cuervo, A. M & L.

Céspedes-Arias. 2023. The type of Setophaga ruficoronata is a hybrid:

implications for the taxonomy of Myioborus warblers. Zootaxa 5383(4):

476-490.

Gary Stiles, June 2024

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Comments from Del-Rio: “YES for B, although I believe whole genome +

habitat studies would benefit the understanding of the strength of potential

barriers to reproduction between chrysops and bairdi.

In the meantime the five taxa should be treated as species.”

Comments from Areta: “YES for A. The species-limits in this

complex are not easy to sort out given the lack of samples from some key areas

and the seeming ability of taxa to interbreed wherever they meet. What a

fascinating system! Genetic divergences are shallow, and support for many of

the mtDNA relationships is poor, although they make a lot of sense in

geographic and plumage terms. Pérez-Emán (2005) uncovered a close relationship

between "ruficoronatus",

chrysops and ornatus. Vocalizations are

structurally very similar across the geographic range of the ornatus-melanocephalus complex, and this applies to albifrons too: all taxa give a rapid series of tonal notes that

includes some shorter and some longer whistles ascending or descending in

frequency that rise and fall in pitch and speed up and increase in amplitude as

the song progresses. All can also duet.

Given that the quite

different-looking bairdi and chrysops hybridize freely and massively

across 200 km, it seems that there are no barriers to interbreeding and that

these two can be considered as part of the same species. The white-faced ornatus is very similar to chrysops, and if one can use the bairdi-chrysops case as a predictor of what would happen if chrysops meets ornatus, the answer would seem to be massive interbreeding. Do the

eastern population of chrysops meet ornatus somewhere? It seems, based on

the examination of a few photographs, that ornatus

at Sumapaz at the southern end of the range have considerably less white on the

face-sides and on the upper-throat (below the bill) [e.g.,

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/151865601;

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/192970091] than birds in the northern end

[e.g., https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/205397261]. This suggests that the

unsampled area between ornatus and

eastern chrysops may well show a

broad area of phenotypic transition.

“The situation

between bairdi and griseonuchus seems relatively

straightforward: the plumage variation reported by Cuervo & Céspedes-Arias

(2023), and the genetic data are consistent with considering them as part of

the same species. Therefore, in my view, also conspecific with chrysops and ornatus.

“The most complicated

part to me is the trans-Marañón divergence between griseonuchus and malaris.

Céspedes-Arias et al. (2021: 12) put it this way: "Genetic structure was

shallow, and only clearly associated with 1 topographic discontinuity of the

cloud forest belt. We found evidence of mtDNA differentiation across the

Marañón River Valley, a dry area that dissects the cloud forest distribution of

M. melanocephalus and coincides with the transition between

rufous-crowned (M. m. griseonuchus) and black-crowned (M. m. malaris)

forms (Zimmer 1949, Curson et al. 1994). This arid valley is important for

differentiation in many other cloud forest birds (Bates and Zink 1994, Chaves

et al. 2011, Gutiérrez- Pinto et al. 2012, Winger and Bates 2015), and likely

acts as a strong barrier for Myioborus taxa restricted to humid

high-elevation forests and scrub (Curson et al. 1994). The exception are 3

specimens from south of the Marañón (Amazonas, Peru), corresponding to the

black-crowned subspecies M. m. malaris, which clustered with individuals

of M. m. griseonuchus and M. m. ruficoronatus occurring north of

the Marañón Valley. This pattern might reflect trans-Marañón introgression

(Winger 2017) or incomplete lineage sorting (Maddison and Knowles 2006)."

Thus, 3 out of 8 samples of the black-crowned malaris from immediately south of the Marañón valley clustered with

the rufous-crowned griseonuchus,

while 5 out of 8 samples of malaris

from the same area clustered with the black-crowned melanocephalus-bolivianus

(see Figures 1A and 2A in Céspedes-Arias et al. 2021). This is only mtDNA data,

but the fact that there is trans-Marañón mtDNA sharing does not instill

confidence on the degree of isolation between the similar (yet differently

crowned) griseonuchus and malaris: if there is leakage across this

barrier, these two sets of taxa would very likely interbreed freely if given a

chance to do so. Here is when having genomic data would provide us with much

needed insights to inform our taxonomic decisions.

“I think that the

most conservative course of action in the light of the great works by C-A et

al. 2021 and C & C-A 2023 is to vote for their "three-species alternative" (Option A). Maybe a genomic

dataset can make my understanding change and result in more splits, but at

present, I think that even the three-species treatment might be on the generous

side of splitting.”

Comments from Robbins: “Of the options given, I vote for A. Given the data at hand, I believe Nacho’s

interpretation of how best to treat these taxa is the best option. Another

option that hasn’t been given is a four species treatment, i.e., albifrons,

ornatus, chrysops, and melanocephalus. By doing the latter,

one does not have to speculate on what might happen if ornatus and

eastern chrysops should be found

in contact. Nonetheless, I find

Nacho’s observation that there may be a cline in white in ornatus or may

even indicate hybridization with eastern chrysops to be plausible. So,

if four species treatment isn’t an option, I vote for option A. Clearly, more

study is needed on what is going on in the Marañón

region with regard to griseonuchus and malaris.”

Comments from

Jaramillo: “YES on B – I can

see both the 3 and 5 species solutions as valid given what we know now. When

the genomic analysis happens, if ever, we will know more. But to me the 5

species solution seems cleaner to me actually. Although super on the fence

here.

Comments from Stiles: “B – 5 species. Here, I comment on Nacho’s conclusion that M.

ornatus s.s. and M. chrysops would show massive interbreeding should

they come into contact, because this has occurred between chrysops and bairdi,

given the shallow genetic divergence in both cases. However, the use of the

latter as a yardstick for predicting the former ignores the complex Andean

topography. The long hybrid zone between chrysops and bairdi occurs

along a continuous range of upper temperate-zone forest habitat, north of which

chrysops occurs alone along the Central Andes at similar elevations for

several hundred km more. The distribution of ornatus s.s. lies between

the northern end of the Cordillera Oriental south to Sumapaz massif. South of

this massif, this cordillera narrows abruptly to a long ridge separated from

the Cordillera Central by the upper Magdalena Valley with tropical elevations

of ca. 350-400m as far south as the latitude of San Agustín. Southward, this

cordillera connects with the Cordillera Central via an eastward extension of

temperate-zone habitat in southeastern Cauca – western Putumayo. The important

point here is that the long ridge south of the Sumapaz massif lowers to

subtropical elevations over much of its length, where the only Myioborus present

is miniatus. At the temperate-zone connection to the south, only chrysops

is found along the highest ridge of this zone – which adjoins the hybrid

zone with bairdi. To the north, the two main cordilleras are separated

by the lower and middle Magdalena Valley which here supports a zone of hot, dry

to moist tropical forest at elevations of 100-200m, over a 50-100+ km wide

zone. Hence, there is NO point of direct contact between chrysops and ornatus

s.s. anywhere in their respective distributions – they are isolated at

least since the latest glacial maximum and given the warming trend of

climatic change, this degree of isolation can

only increase in the coming years.”

Comments from

Bonaccorso: “YES for A. Based

on the available evidence, three species (Myioborus albifrons, M. ornatus, and M. melanocephalus) make sense

(five also, but I think the move would be too bold). Céspedes et al. are

working on a genomic treatment of the whole group, and knowing Laura

(Céspedes), it will be superb. So, we will have more than enough genetic

evidence to consider further splits.”

Comments from Lane: “I am not entirely clear of the accepted

phylogeny within this clade, but the evidence provided makes me think that

there are a couple of other taxonomic options that are not offered here

(namely, 2 species [M. albifrons and M. melanocephalus, including

all remaining taxa of the complex] and 4 species. The one I would favor, based

on what I am seeing here is: 4 species.

1. M. albifrons (monotypic)

2. M. ornatus (monotypic)

3. M. chrysops (assuming that it is

decided to be the name with priority over M. bairdi, and also including M.

griseonuchus. The broad hybrid swarm zone seems to make this a necessity)

4. M. melanocephalus (including malaris

and bolivianus).

“Did I miss some

reasoning why this taxonomy was not considered an option? So, NO for any of the

three options offered in the proposal.”

Additional comments

from Areta: “Thanks Gary for

clarifying that the gap between ornatus and chrysops is real. In no way have I ignored the

complex Andean topography in my reasoning. However, the meager plumage, vocal,

and genetic differences that we know at present, leave ornata as a very weak species in my perspective,

and I still stand by the yardstick approach that it is better considered a

subspecies of chrysops. It is

great to hear that Laura is working on a genomic perspective on these Myioborus. I am eager to see what

she finds, and to revise my vote accordingly.”

Comments from

Claramunt: “YES to A. Three

species. The new information clearly shows gene flow and introgression between chrysops and bairdi, demonstrating that

they are not separate species. Not much we can say about the rest of the

complex, but I agree in maintaining albifrons and melanocephalus as separate species for now.”