Proposal (1006) to South

American Classification Committee

Treat Amazona guatemalae as a separate species

from A. farinosa (Mealy Parrot)

Note from Remsen: This

is a NACC proposal (2023-A-16) that was rejected that I am posting here, with

permissions) because it has the potential to affect the distribution and

component taxa of what we currently classify as Amazona farinosa. You can see official comments from NACC

voters here; the

vote was 7 to 5 to reject.

Background:

The Mealy Parrot (Amazona farinosa) occurs in southern

Mexico, through all of Central America, parts of northern South America and the

Amazon Basin, and also has a disjunct population in the Atlantic Forest of

Brazil. Most authorities currently recognize 3-5 subspecies of A. farinosa, which are often split into

two groups (sensu Clements et al. 2021): the Northern Mealy Parrot (A. f. guatemalae from the Caribbean

slope of southeastern Mexico to northwestern Honduras and A. f. virenticeps from the Sula Valley of Honduras to extreme w

Panama) and the Southern Mealy Parrot (A.

f. farinosa, which occurs east and south from Panama to Colombia, Peru,

Bolivia, the Guianas, and disjunctly in the Atlantic Forest of southeastern

Brazil). Although most authorities consider the Southern Mealy Parrot to be

monotypic, it is sometimes split into three subspecies, including A. f. Inornata (Panama and Colombia), A. f. chapmani (SE Peru to NW Bolivia),

and A. f. farinosa in the central

Amazon Basin and Atlantic Forest.

Until recent HBW-Birdlife and

IOC splits, the two putative species have been treated as conspecific. HBW-BL

split A. farinosa into two species

based on the following rationale.

Until

recently, [guatemalae] was considered

conspecific with A. farinosa, but

differs in its yellow vs red lower carpal edge (2); blue-suffused (or blue)

crown with broader, more heavily scaled nape feathers forming frequently or

usually ruffled ruff or cape (3); blackish vs pale bill (2); black bristles on

nares more extensive, and black shaft streaks on face (lores to below eye)

(ns1); less powdery plumage (ns1); more oblong, less circular and slightly less

broad white eye-patch (mensural score: allow 1). This split is supported by

molecular analysis (Wenner, Russello & Wright 2012).

The IOC note on this issue is:

"Northern Mealy Amazon is split from [Southern] Mealy Amazon (Wenner et

al. 2012; HBW Alive)."

As suggested above, this

proposed split is largely based on slight differences in plumage coloration

between the Northern Mealy Parrot and Southern Mealy Parrot groups with support

from population genetic data. The NACC and SACC have not yet considered these

data in voting on species limits within the Mealy Parrot complex.

New

Information:

Morphology:

This is not new information

per se, but rather a synopsis of phenotypic differences between the Northern

Mealy Parrot and Southern Mealy Parrot groups.

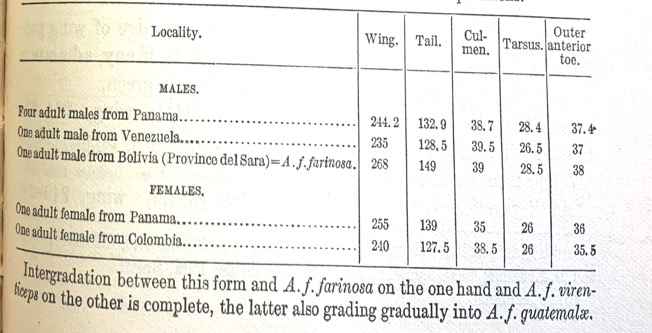

Ridgway (1916) determined that

phenotypic variation between Central and South American lineages was clinal

(Table 1). Although we assume that Ridgway was referring to the morphometric

measurements that appear directly above his statement about intergradation,

it’s not absolutely clear whether he was referring to morphometrics, color, or

some other aspect of phenotype.

Table 1: From Ridgway (1916),

morphometric measurements of A. f. inornata and statement beneath

stating that intergradation occurs between A. f. farinosa and A. f.

virenticeps. We are unclear based on the placement of this statement what

characters Ridgway (1916) was referring to, but believe the statement was in

reference to morphometric characters.

In contrast, Wetmore (1968)

noted that farinosa (inornata from Panama) averaged larger in wing, tail, culmen

(from cere), and tarsus length (Table 2). As mentioned above, the HBW split was

based on the minor plumage differences summarized here. Bill color differs

between the two, being pale in southern and blackish in northern. Crown color

is blue or suffused blue in Northern Mealy Parrot while Southern Mealy Parrot

lacks blue in the crown. Although Southern Mealy Parrots tend to show yellow in

their crowns more often, some Northern Mealy Parrots also have yellow in their crowns.

Northern Mealy Parrots also typically have more heavy scaling on their nape.

Other differences include a yellow lower carpal edge in Northern Mealy Parrot,

whereas this is red, yellow, or a combination of both in Southern Mealy Parrot.

Also, Northern Mealy Parrots tend to have more extensive bristles on nares and

shaft streaks on the face, less “powdery” plumage, and a more oblong and

narrower white eye patch compared to Southern Mealy Parrots.

Table 2. Wetmore (1968)

measurements

|

|

wing |

tail |

Culmen

from cere |

tarsus |

|

virenticeps male

(n=9) |

229.5

mm |

122.9

mm |

34.6

mm |

28.1

mm |

|

virenticeps female

(n=8) |

225.4

mm |

123.7

mm |

34.6

mm |

28.1

mm |

|

inornata male

(n=10) |

235

mm |

131.7

mm |

36.3

mm |

29.3

mm |

|

inornata female

(n=8) |

233.8

mm |

132.7

mm |

36.4

mm |

28.6

mm |

Below are Macaulay Library

photos showing variation in some of these features, especially bill, crown, and

eye ring.

Northern

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/433053151

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/439969671

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/465517171

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/432513681

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/417454551

Southern

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/364752721

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/422619441

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/364752631

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/406771601

Population

genetics:

Wenner et al. (2012) sequenced

two mtDNA gene regions (1,157 bp of Cyt b + COI combined) and two nuDNA introns

(1,145 bp of TGFB2 + TROP combined) to examine phylogenetic structure among the

five recognized subspecies of A. farinosa

(Fig. 1). Hellmich et al. (2021) expanded on this study to include samples

of the geographically disjunct Atlantic Forest population of the nominate A. f. farinosa. Aside from the addition

of the Atlantic Forest population, the two data sets are identical. Although

both nuDNA and mtDNA were included in these studies, the sampling matrix is

incomplete such that multiple individuals are missing data from one or more

loci or gene regions. Additionally, the number of parsimony-informative sites

in the mtDNA data set (n = 96) was far more than the nuDNA data set (n = 5),

such that the concatenated / combined phylogenetic data sets are largely driven

by information contained in the mtDNA genome.

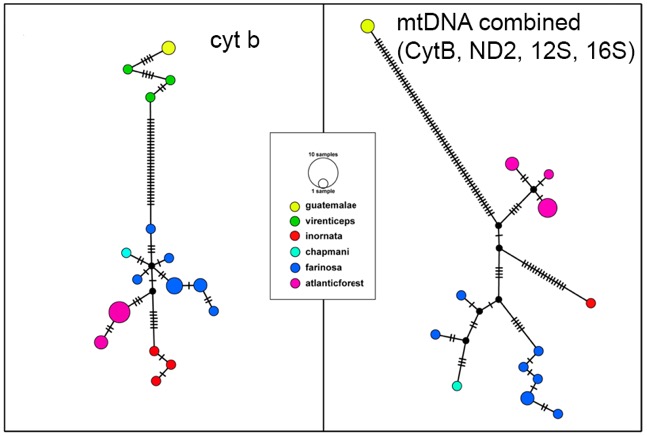

Wenner et al. (2012) recovered

16 cyt-b haplotypes with 28 sequence differences between Northern Mealy Parrot

and Southern Mealy Parrot clades (Fig. 2). This corresponded to mtDNA distances

of 3.5–5.4% between the two clades, which translates to an approximate

divergence time of 1.75–2.7 mya during the late Pliocene to early Pleistocene.

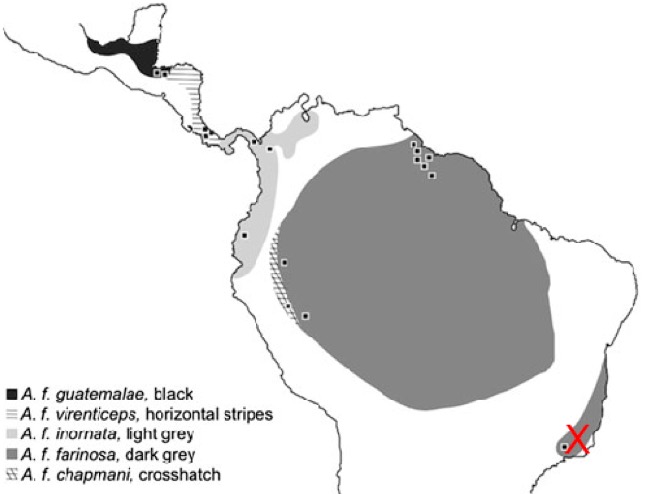

Figure

1: Sampling localities and ranges of currently recognized subspecies. Red “X”

indicates approximate locality of additional samples from the Atlantic Forest

of Brazil that were included by Hellmich et al. (2021).

Figure 2: (Left panel) Median

joining haplotype network based on CytB data. Size of each circle corresponds

to the number of individuals sharing that haplotype and color to each clade.

(Right panel) Median joining haplotype network based on 4 mitochondrial genes

(CytB, ND2, 12S, 16S). Size of each circle corresponds to the number of

individuals sharing that haplotype and color to each clade. Ticks on each

branch represent the number of sequence differences between each haplotype.

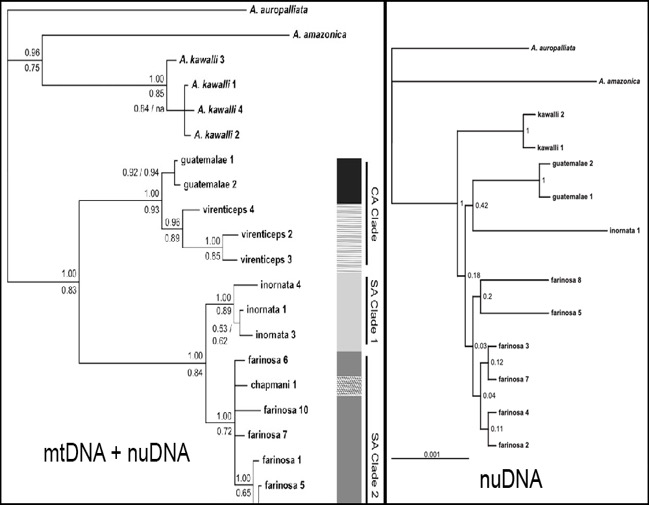

Using their combined data set

of mtDNA + nuDNA, Wenner et al. (2012) recovered reciprocal monophyly and a

deep phylogenetic split between the Northern Mealy Parrot (virenticeps and guatemalae) and the Southern Mealy Parrot (farinosa, inornata, and chapmani).

The nuDNA tree with the highest maximum likelihood score had very low bootstrap

support for all of the nodes within the Mealy Parrot complex, essentially

producing a polytomy (Fig. 3). Additional sampling of the Atlantic Forest

population by Hellmich et al. (2021) recovered the same topology, and found

that the Atlantic Forest population formed a monophyletic group (Fig. 4).

Figure 3: Phylogenies from combined mtDNA + nuDNA (left) and nuDNA alone

(right) of Mealy Parrots from Wenner et al. (2012). Posterior probabilities are

shown above each node while maximum likelihood bootstrap values are shown

below, or to the side for the nuDNA alone phylogeny.

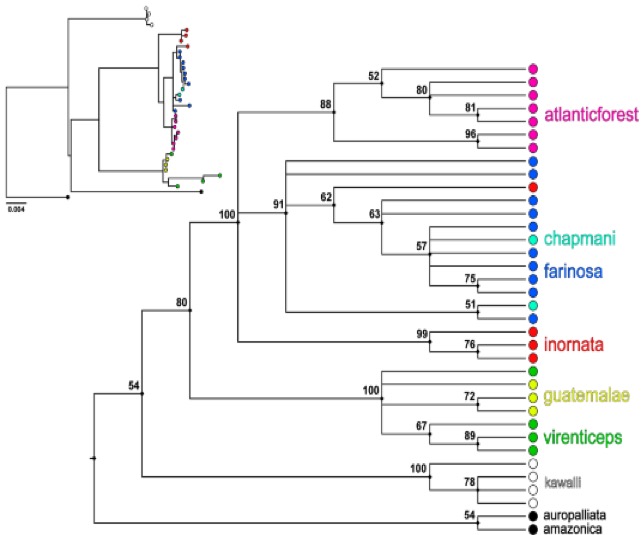

Figure 4: Maximum likelihood

majority rule consensus tree (cladogram without branch lengths) based on

combined nuDNA and mtDNA from Hellmich et al. (2021) with expanded Atlantic

Forest sampling. Numbers to the left of each node are bootstrap consensus values.

Top-left inset is a phylogram with branch lengths included that are

proportional to sequence divergence.

Vocalizations:

Hellmich et al. (2021) used

150 samples of contact calls (Fig. 5) to investigate differences in call

structure across the 5 subspecies and the Brazilian Atlantic forest

populations. They found that variation within each subspecies was as great as

between subspecies with substantial overlap in acoustic principal component

space among clades (Fig. 6). They also found no correlation between genetic

differentiation and vocal differentiation among clades.

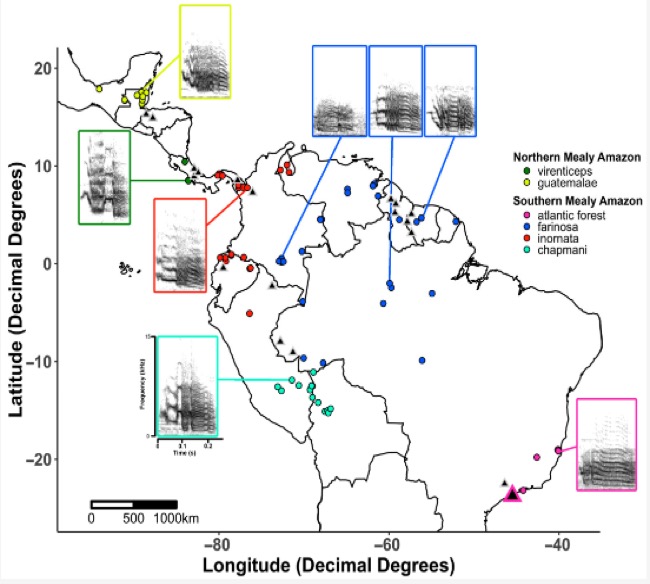

Figure 5: Map of vocal and

genetic sampling locations from Hellmich et al. (2021). Spectrograms of

representative calls from each clade are shown at their corresponding recording

location. Genetic samples from the Wenner et al. (2012) study are indicated by

grey-outlined triangles on the map. The location of the new genetic samples

included in Hellmich et al. (2021) is indicated by the purple-outlined

triangle.

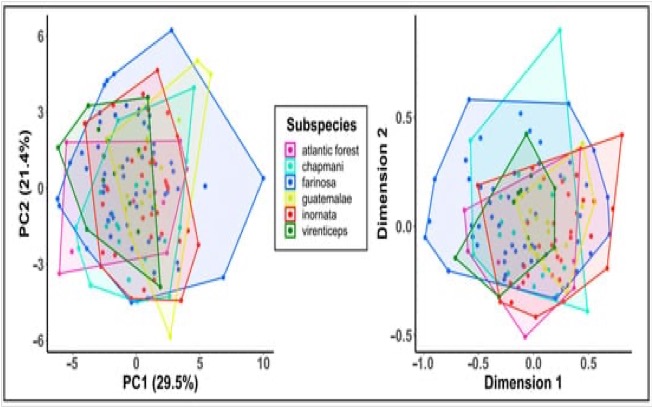

Figure

6: Acoustic variation in call data. Plots of acoustic variation in contact

calls based on principal components analysis of 27 call measures (left) and a multidimensional scaling of

spectrogram cross-correlation values (right).

The points represent individual calls, and the polygons represent the total

area occupied by each clade’s set of calls in acoustic space. This is Figure 4

from Hellmich et al. (2021).

Recommendation:

Phenotypic differences between

these groups are very slight—being limited to a few plumage characters that are

not diagnostic—and may be clinal through the Isthmus of Panama. Vocalizations

are variable throughout the complex and do not differ consistently between

northern and southern groups. Although there is substantial mtDNA divergence

(3.5–5.4%), no shared haplotypes, and reciprocal monophyly between the northern

and southern groups, there is still a lot of uncertainty regarding contact zone

dynamics. Most authorities state that the northern and southern groups are

allopatric, but the evidence for this is unclear, and the distance between them

is also unknown. Based on eBird records, the two groups appear to be separated

by a narrow gap (~50 km) in central Panama, but current sampling for genetic

analyses from the putative contact zone is sparse, and these subspecies can be

difficult to distinguish in the field. Thus, the contact zone remains largely

uncharacterized, both in terms of phenotypic and genetic differentiation. Mealy

Parrots have also been commonly held in captivity throughout the region, both

currently and historically by indigenous communities, which has increased

opportunities for escapees to come into contact.

Taken together, we feel that

although there is considerable evidence for cryptic speciation based on mtDNA

divergence, the small amount of nuDNA is largely uninformative and does not

recover the same pattern of deep reciprocal monophyly between Northern and

Southern Mealy Parrots. Furthermore, the phenotypic differences are slight

compared to other Amazona sister

species, and the potential for hybridization in the contact zone remains

unstudied. Acting conservatively, we therefore feel that Northern and Southern

Mealy Parrots should not be split.

We recommend a NO vote on this

proposal.

Literature

Cited:

Clements,

J., T. Schulenberg, S. Billerman, T. Fredericks, J. Gerbracht, D. Lepage, B.

Sullivan, and C. Wood (2021). The eBird/Clements checklist of Birds of the

World: v2021. Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Hellmich,

D. L., A. B. S. Saidenberg, and T. F. Wright (2021). Genetic, but not

behavioral, evidence supports the distinctiveness of the Mealy Amazon Parrot in

the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Diversity 13:273.

Ridgway,

R (1916). The birds of North and Middle America. Part 7. Bulletin U.S National

Museum 50.

Wenner,

T. J., M. A. Russello, and T. F. Wright (2012). Cryptic species in a

Neotropical parrot: genetic variation within the Amazona farinosa species

complex and its conservation implications. Conservation Genetics 13:1427–1432.

Wetmore, A. (1968). The Birds of the Republic of Panama. Part 2.

Columbidae (Pigeons) to Picidae (Woodpeckers). Smithsonian Miscellaneous

Collections 150. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

David Vander Pluym and Nicholas A. Mason,

June 2024

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Vote tracking chart:

https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart968-1043.htm

Comments

from Remsen:

“NO, as I voted in the NACC proposal, and for all the reasons given in the

proposal. There’s a potential contact

zone in Panama, and that needs to be adequately characterized.”

Comments

from Areta:

“NO: the Panama area should be rigorously screened, phenotypic

distinctions are minor, the discordance between mt and nuc DNA suggests

caution, and the vocalizations (that tend to be well-marked in Amazona species) appear as a single

cluster in the quantitative vocal analyses.”

Comments

from Robbins:

“NO, for all the reasons detailed in the proposal.”

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“YES – I will be the outlier. Back when I used to see elements of this group on

tours, I was always surprised that the Central American birds just seemed quite

different to me from the South American birds. That is not all that useful, but

obviously part of why I am more permissive with this topic. The DNA data tells

a partial story, but there is a signal there. I realize that most will likely

vote this down, but I am persuaded. I do wish that sometimes we had some

information from the parrot breeder people, I bet they see similarities and

differences between populations that we do not, and with the right context,

these could be useful in making some of these decisions.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“NO. As noted by Van and others, the central Panama area would be a contact

zone critical for separating the northern and South American groups: here,

genetic and phenotypic information are needed: are they parapatric, or do they

intergrade?”

Comments

from Lane:

“NO to splitting the two groups of A. farinosa. The evidence provided in

the proposal suggests that they are not sufficiently distinctive with respect

to one another to warrant a split. Further, I am not sure what to do with Amazona

voices. In some situations, particularly when in syntopy, they are clearly very

important characters for species recognition. But when dealing with populations

at several points within a species’ or taxon group’s range, I have been seeing

some serious issues that (what I assume is) dialect formation can introduce.

Obviously, parrots can and do learn their vocabulary, but we largely accept

that there are common vocalizations (flight calls, particularly) that are

fairly uniform over the majority of the distribution of any given species

(using the term loosely here). But, for example, I first learned the voice of Amazona

autumnalis from birds in Tamaulipas, Mexico, which sound like this (https://xeno-canto.org/28759; a very distinctive

“CHEE-colek”), and then encountered them in Belize, where they sounded

different (https://xeno-canto.org/28345; a shorter “TOE-tick”

that still has a distinctly bisyllabic structure), but I thought I still

detected enough similarity that it didn’t really faze me. Then, a few years

ago, I encountered the species on the Gulf slope of Oaxaca (intermediate

between the previous two sites), and was blown away by how different they

sounded there (https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/79933521, which lacked any

bisyllabic construction at all)! In fact, I was misidentifying those birds as A.

farinosa guatemalae until I was able to see the source! I should note that

all three populations are considered to fall under the same, nominate,

subspecies of A. autumnalis. I realize that this proposal is about A.

farinosa and not A. autumnalis, but since these are congeners, I

think it may be useful to infer from that species that the fact that the voices

within the populations of the A. farinosa complex don’t match genetic

populations may not be at all surprising here.”

Comments

from Claramunt:

“NO. Only mitochondrial DNA suggests the split; other types of data are

ambiguous or not diagnostic.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“NO. The conflicting

interpretations resulting from mitochondrial DNA analysis versus nuclear DNA

analysis do give pause, the morphological differences don’t (in my opinion)

meet the ‘yardstick’ test within the genus, there are no apparent diagnostic

vocal differences between the two groups, and we lack data on all of the above

from the potential contact zone in central Panama.”