Proposal (1008) to South

American Classification Committee

Treat Tunchiornis ochraceiceps

(Tawny-crowned Greenlet) as consisting of four species

Effect

on SACC list: This proposal would treat our current Tunchiornis

ochraceiceps as consisting of four species.

Background: Our current Note reads as follows:

14a. See Ridgely & Tudor (1989) for potential reasons for ranking of the southern rubrifrons subspecies group as a separate species from Hylophilus ochraceiceps. Slager et al. (2014) found deep divergences within among lineages included in H. ochraceiceps. Del Hoyo & Collar (2016) treated luteifrons of the Guianan Shield as a separate species (“Olive-crowned Greenlet”) based in part on Slager et al. (2014) and also on vocal differences pointed out by Boesman (2016h). Buainain et al. (2021) found evidence for treating it as consisting at four species; they found that luteifrons is sister to the rubrifrons group of southeastern Amazonia, treated as conspecific with ochraceiceps by del Hoyo & Collar (2016). SACC proposal badly needed.

Tunchiornis

ochraceiceps

(Tawny-crowned Greenlet) is a polytypic species with a large distribution in

the Neotropics; 10 subspecies occur from s. Mexico to southern Amazonia. They have always been treated as part of the

same species (as far as I know), e.g., Hellmayr 1936, Blake 1968 “Peters”,

Meyer de Schauensee 1970). The only

major break in the distribution is across the Andes, with the number of

subspecies equally divided between trans-Andean and cis-Andean populations. It is treated as a single species by

Dickinson & Christidis (2014) and IOC (v. 13.2; 2023).

Boesman

(2016) sampled 6 recordings of trans-Andean ochraceiceps, 9 of the

Amazonian ferrugineifrons-rubrifrons group, and 8 of Guianan

Shield luteifrons. Unfortunately,

the locations and subspecies allocations were not reported, so for example

there is no way to know which Amazonian taxa were sampled, which is critical

given that Buainain et al. considered ferrugineifrons and rubrifrons

to be separate species. Boesman found

that luteifrons differed strongly from his other two groups: “Surprisingly, the different song of luteifrons

has seemingly nowhere been picked up in literature: its song consists of two

notes with decreasing pitch (score 4), resulting in an overall longer song

phrase (score 2-3) and larger frequency range (score 1-2). When applying Tobias

criteria, this would lead to a total vocal score of about 5 vs. all other races.”

And “All in all, we can conclude that the Guianan group

clearly stands apart vocally.”

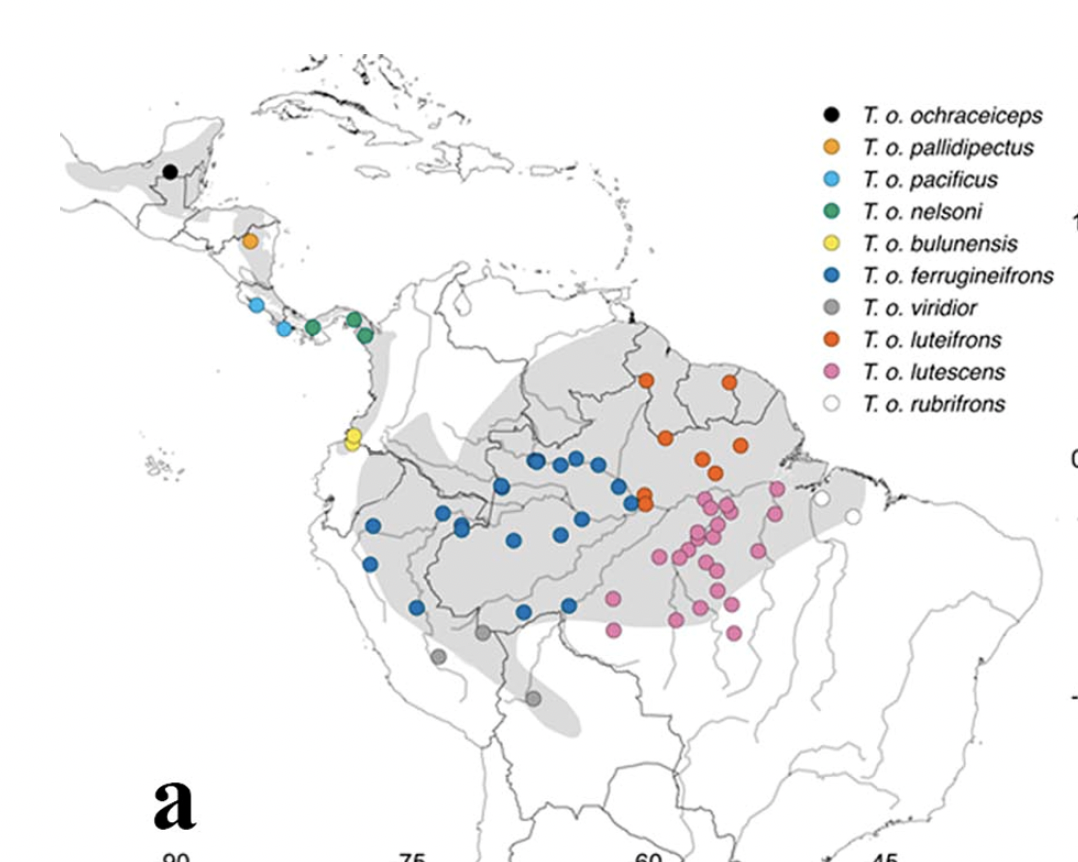

Here's

the map (from Buainain et al. 2021), which will be useful in evaluating the

proposal:

New

information:

Nelson Buainain and colleagues used 625 specimens, 152 vocal recordings, and 69

tissue samples, with complete taxonomic and broad geographic sampling. The genetic results were based on UCE data

from 2267 usable loci. The vocal results

were based on analysis of a typical range of characters quantified from

sonograms. Standard morphometric

measurements were used to evaluate morphological differences. Plumage variation was analyzed by applying

Smithe color names and also by simultaneous comparisons of a large series of

specimens assembled at the AMNH; photographs of all type specimens were

examined as well as all original descriptions.

This is another outstanding empirical study coming out of Brazil.

A

detailed synopsis of all these data would take too much space here. The analyses are detailed and objective. My favorite is the Estimated Effective

Migration Surface analysis in Fig. 3 – cool stuff. The basic point that

this bird consists of a bunch of old lineages with minimal phenotypic

differentiation is biologically important, and as analyses of Neotropical

lineages in this detail increase, through a comparative framework perhaps we

will gain a better idea for why some change quickly whereas others do not. If I’d reviewed the paper, I would have

pointed out that one of Joel’s own papers could have been used to illustrate

conservative phenotypic evolution in the group: Reddy & Cracraft (2007; MPE

44: 1352-1357) showed that two Indomalayan genera are actually sister New World

vireos, and in fact Indomalayan Erpornis looks remarkably like a Hylophilus

sensu lato despite ca. 30 MY of separation, and some Indomalayan Pteruthius

resemble Vireolanius. Anyway, congrats

to the authors on a great paper. Check

out the details for yourselves. My only

criticism is that when they listed their four species, a Diagnosis for each,

summarizing their data, would have been very useful. As is, one has to backtrack through the paper

to piece together the characters used to delimit the four species-level taxa

(and two additional subspecies-level taxa).

From

the standpoint of taxonomy, here’s what stands out to me:

Plumage: Of consequence to

eventually incorporating subspecies taxonomy into SACC, only two of the five trans-Andean

subspecies is 100% diagnosable. The plumage

variation is almost all clinal, from s. Mexico to nw. Ecuador, with a blip due

to Gloger’s Rule, according to their analyses.

However, no official tests of diagnosability were conducted on the

plumage data, which constitutes the basis of the subspecies original

descriptions; rather than simply point out that they were not diagnosable, perhaps

a better approach would have been to show that quantitatively to see what the

level of diagnosability is because even the most rigid application of PSC-like

thinking allows for something below 100% diagnosability. Before synonymizing all 5 subspecies, the

data should be re-evaluated from this standpoint; the pattern is clearly

clinal, but is it a step cline, with each of the 5 subspecies representing

plateaus? The subspecies nelsoni is

stated as intermediate between northern ochraceiceps and bulunensis of the Chocó, and is also clearly a

genetically admixed population of the two in terms of mtDNA, but is it a

phenotypically diagnosable unit? The

text mentions differences in iris color between some groups, but apparently

these are not fixed.

Three subspecies groups are, however,

diagnosable by head coloration, and these are two of the taxa that they

proposed to be elevated to species rank (see below): T. luteifrons of

the Guianan Shield and T. rubrifrons of SE Amazonia. However, they evidently could not diagnose

the Middle American ochraceiceps group from ferrugineifrons from

W Amazonia, although they stated that there are trends in coloration that

correspond to these groupings. Thus, it

is also not clear to me now whether the two subspecies taxa retained in their

classification are diagnosable only as mtDNA lineages, in which case there is

no basis for recognition as subspecies, in my opinion. I’m confused.

Perhaps all of this explained and detailed in

Supplementary Information, although there is no text reference to such files on

morphology. For some reason, I cannot

access the SI.

Morphometrics: None of the taxa,

even those ranked as species by the authors, is diagnosable by

morphometrics. No surprise there.

Vocalizations: Vocalizations of

course are critical to species limits in the Vireonidae. As far as I know, all taxa recognized as

species in the family differ in vocalizations.

For several decades, I’ve heard through others that vocal differences were

notable among some of the populations of T. ochraceiceps. Therefore, I was expecting their analysis of

150+ recordings to confirm the discrete differences I had heard discussed. Here is their lead sentence:

“The

qualitative analysis shows no diagnostic vocal characters for any of the

populations of T. ochraceiceps (Fig. 8a–d). Some variation, however, is

noteworthy and a relatively reliable indicator of population assignment.”

They

provided the following comments on the vocal differences among their geographic

groups, for which I am adding their proposed species name rather than the

geographic clusters in the paper:

•

ochraceiceps: “The trans-Andean

forms tend to have higher frequency (higher pitch) songs (Fig. 9c-g), although

there is much overlap with other populations.”

•

luteifrons: “The NEA populations

east of the Branco River, predominantly produced a distinct song with two

whistled syllables, between the frequencies of ~ 2.7–3.8 KHz,

being the last syllable descending in modulation. However, it is clear that

these birds can eventually produce one syllable vocalizations (ML 80429, NB

observation during field work around Manaus, AM, Brazil) that are apparently

indistinguishable from songs with one syllable from the other populations.”

•

rubrifrons: “All recordings from

the Madeira-Tapajos ´ interfluve, in SEA, contained a distinct song with two to

three syllables, between the frequencies 2.8–3.5 KHz,

but with ascending second and third syllables, thus different from the NEA

population in modulation. However, songs with one and two syllables were

recorded in the Juruena-Teles Pires (whose confluence form the Tapajos River)

interfluve. This area lies in the limit between the single and multiple

syllable song populations in SEA. Thus, although some interesting difference in

frequency of vocal pattern exist, it is not possible to unmistakably

distinguish populations by their songs.”

•

ferrugineifrons: [not really discussed per se, as far as I can tell, but

see graph below]

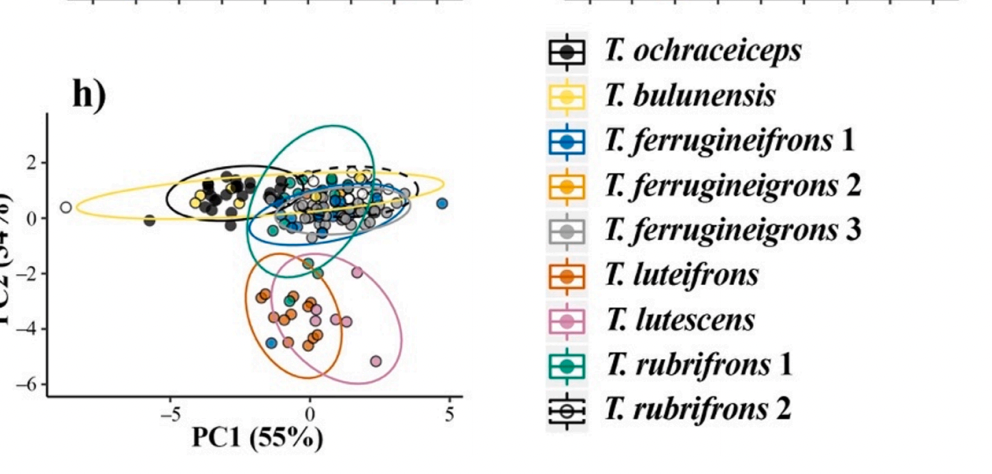

Here

is their Fig. 9h, which is a PCA classification of quantitative vocal

characters:

I

find this figure difficult to decipher, but what stands out to mw is that there

are 3 clusters: (1) upper left, which corresponds mainly to the nominate

ochraceiceps group, but also some portion of the Chocó taxon bulunensis (accidentally treated as a species

in the legend); upper right, which is a supo of rubrifrons and ferrugineifrons

1, “ferrugineigrons” 3 [unfortunately conspicuous

typo missed by 8 authors, and an unknown number of editors and reviewers], and

some bulunensis; perhaps due to poor eyesight,

I cannot spot where T. “ferrugineigrons” 2 is;

and (3) T. luteifrons and what is marked as T. lutescens, which

they consider a subspecies of T. rubrifrons in their

classification. Thus, I really don’t

know what to make of all this. As noted

in their lead sentence above, the authors stated upfront that none of the

populations have diagnostic vocal characters.

Certainly, as far as I can tell, vocal differences seem somewhat chaotic

and don’t map well on to their genetic groups.

I hope someone else can dig further into this in case I am

misinterpreting something.

With

all appropriate caveats from concluding anything from single recordings, here

are a few I picked out from xeno-canto.

This is tedious because the number of recordists who rate their

recordings as “A” quality have obviously never listened to, for example, an

Andrew Spencer recording among others, so you have to wade through lot of

mediocre recordings to get to a good one.

I think xeno-canto is one of the world’s great bird resources; I just

wish there was a more objective way to rate recordings other than self-rating,

so that the truly best would come nearest the top.

• ochraceiceps (from Puntarenas, Costa

Rica, by Peter Boesman): https://xeno-canto.org/274157

• luteifrons (from Brownsberg,

Suriname, by Peter Boesman): https://xeno-canto.org/271834

• ferrugineifrons (Rîo

Javarí, Peru, by Peter Boesman) https://xeno-canto.org/270735

• rubrifrons (Cristalino

Lodge, n. Mato Grosso, Brazil, by Frank Lambert): https://xeno-canto.org/68496

From

the standpoint of someone who was familiar (once upon a time) only with ferrugineifrons

from Bolivia, these all basically sound similar to someone not embedded in the

greenlet voice universe; even the two-noted luteifrons doesn’t sound

radically different from the others.

Genetic

divergence:

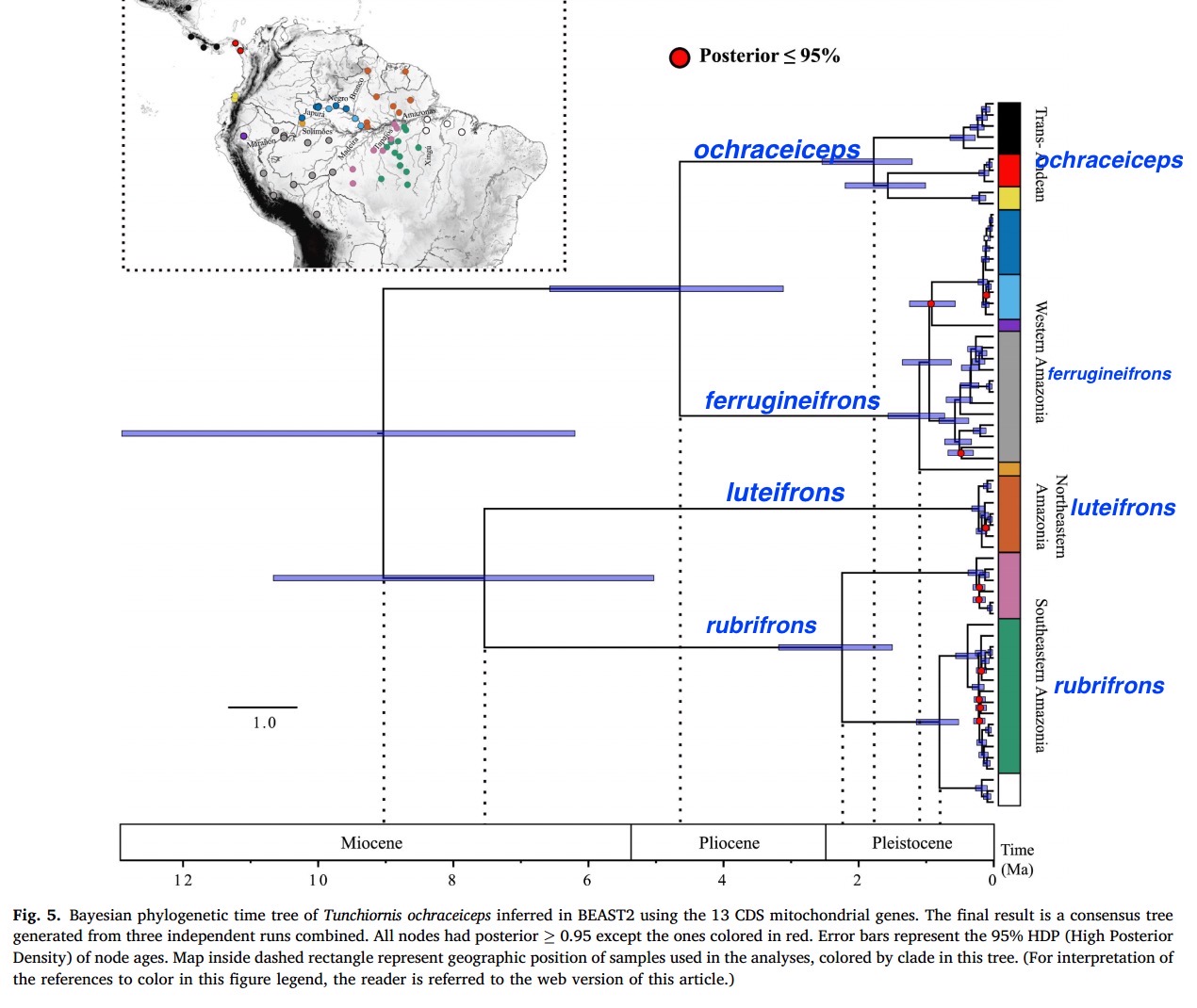

Here is their main figure. I have superimposed the four proposed species

name in blue on each cluster. Obviously T.

ochraceifrons consist of four fairly old lineages in terms of

mtDNA. The estimated divergence time of

the ochraceiceps cluster from the ferrugineifrons cluster is

almost 5 MYA (Pliocene), which is older than many crown lineages we rank as

species. The separation of the crown

lineages luteifrons and rubrifrons is much older, ca. 7.5. MYA

(Miocene), i.e. older than many crown lineages we rank at the genus level. I do not have the qualifications to evaluate

their time calibrations, but taken at face value, they certainly are consistent

with species rank.

A

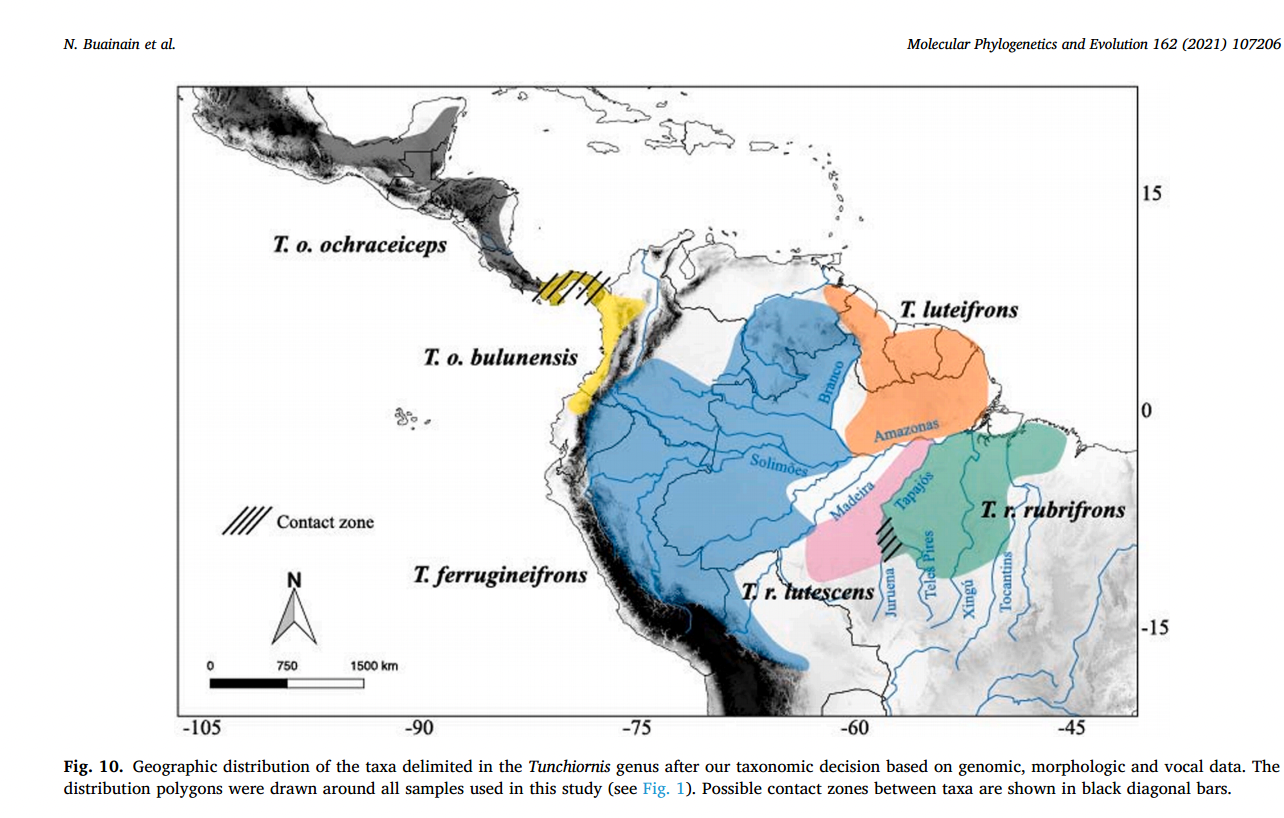

summary of their recommended species classification is as follows:

• Tunchiornis

ochraceiceps:

s. Mexico through Central America to nw. Colombia and south in Chocó region to

nw. Ecuador; includes T. o. bulunensis.

• Tunchiornis

ferrugineifrons

(Sclater, 1862): w. Amazonia, from W of Rio Branco through s. Venezuela,

se. Colombia, e. Ecuador, e. Peru, and ne. Bolivia to w. bank of Rio Madeira in

sw. Amazonian Brazil.

• Tunchiornis

luteifrons

(Sclater, 1891): Guianan Shield east of Rio Branco through the Guianas to n. Pará and Amapá to n. bank

of Amazon.

•

Tunchiornis rubrifrons (Sclater & Salvin, 1867): s. Amazonia S of the Amazon from

Rio Madeira east to Rio Tocantins and se. Pará (?and w. Maranhão), including T.

r. lutescens)

Here

is their figure with geographic distributions and subspecies/species

classification

Discussion: Basically, my impression is that the data are

terrific, but the interpretations of the analyses are insufficiently clear, at

least to me, for sorting it all out in terms of taxonomy. The genetic results scream out for

recognition of at least four species, but when one tries to diagnose these

vocally, it falls apart, with a few instances of songs mismatched to genetic

group and no crystal clear vocal groups.

I suspect a reanalysis of plumage characters would reveal not just three

but at least four and probably many more phenotypically diagnosable units. Central to the problem is that luteifrons

appears to be the most distinctive taxon in terms of both voice and plumage (no

rufous color on crown or face), yet it is sister to rubrifrons, which

cannot be separated, evidently, from ferrugineifrons vocally. So, what we have here is a case of unequal

rates of character evolution, which poses a dilemma for species concepts.

Biologically, this is a fascinating

situation. Genetically, the results seem

crystal clear and tidy, but once one tries to integrate this with plumage and

voice, it’s a mess. The authors say as

much in the paper. Do we go with the

deep genetic divergence and ignore apparent lack of phenotypic

distinctiveness? Vireonidae has may

cases of barely differentiated taxa treated as species, e.g. most recently Vireo

chivi and V. olivaceus.

I have no recommendation either way –

I’m going to see what others say, especially with regard to voice.

For

voting, let’s do it this way:

YES

= Recognize

4 species, as per recommendations in the paper.

NO

= Do

not recognize 4 species at this point but maintain status quo, at least

temporarily, with acknowledgement that the complex may contain 1, 2, 3, or 4

species pending further evaluation.

English

names: If the proposal passes, then we will need a

separate proposal on English names,

References:

Boesman, P.F.D. 2016.

Notes on the vocalizations of Tawny-crowned Greenlet (Hylophilus ochraceiceps). Ornithological Note 168. Birds of the World, Cornell Lab of

Ornithology.

BUAINAIN, N., M. F.A.

MAXIMIANO, M. FERREIRA, A. ALEIXO, B. C. FAIRCLOTH, R. T. BRUMFIELD, J.

CRACRAFT, AND C. C. RIBAS. 2021. Multiple species and deep genomic divergences

despite little phenotypic differentiation in an ancient Neotropical songbird, Tunchiornis

ochraceiceps (Sclater, 1860) (Aves: Vireonidae). Molecular Phylogenetics Evolution 162:

107206.

Van Remsen, September

2021 rev. June 2024

Vote tracking chart:

https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart968-1043.htm

Comments

from Areta:

“YES. I vote for the 4-way split. The

deep genetic differences coupled with somewhat different vocalizations,

plumages and eye-color, indicate that keeping all these taxa as a single

species is incorrect. I share Van´s misgivings on how the information is

organized and summarized, and I think that more detailed vocal analyses will

uncover more clear vocal distinctions among the four main species-level taxa.”

Comments

from Claramunt:

“YES. I think the proposed taxonomy is a step

forward. The data clearly show that there are multiple species-level lineages

in this complex and the proposed splits are supported by evidence.”

Comments

from Robbins:

“Unless one strictly relies on the mtDNA for making species allocations, this

is messy from a vocal and plumage morphology standpoint. An example of vocal

issues, I have recorded birds in Nicaragua and Guyana that both give single and

two-noted calls that are very similar. Listening to recordings from elsewhere I

get the same impression as what is stated in the paper, seems to be no

diagnosable song for each of the four clades.

As Van pointed out, conservative plumage morphology may be clinal and it

is unclear whether there are diagnosable characters for each clade. Unless I

missed something, it is unclear if there are consistent differences in eye

color. So, I’m on the fence on this one and look forward to seeing comments by

others.”

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“YES – This is a complicated group with lack of outstanding plumage features to

work with. I guess this is why they call them greenlets. In any case, I am

persuaded by the data here and the summary that Van provides. All Vireonidae

differ in vocalizations – Van have you heard singing Philadelphia Vireos? Even

the Red-eyes can’t tell them apart!! But yes, their calls are different.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“YES. The 4-way split of Tunchiornis seems well justified – it certainly

is a long step forward in understanding Tunchiornis and serves as a

solid base should additional data indicate further splitting in the future.”

Comments

from Lane:

“NO. Ugh. This is one of those cases that just doesn’t really feel like it is

cooked enough to take out of the oven. I guess we can just take the molecular

results and shrug at the fact that the plumage and voice data don’t map well

onto them. I just did a quick search as per Alvaro’s comments to see if there

are enough recordings of calls to provide support in that group of

vocalizations being stronger evidence for differences, but there are very few

call recordings (at least in X-c) for several of the

taxonomic groups so it is hard to say. I really would rather wait for more

evidence to elucidate the situation before accepting splits here. NO.”

Comments

from Andrew Spencer (who has Remsen vote): “YES - this was a really tough vote

for me. No one factor convinces me that these should be split, but when taken

together they tip me into the yes camp. Regarding vocalizations, as others

have already stated here, the situation seems really murky. Listening

to recordings, I do get the general patterns laid out by Boesman and expanded

on by Buainain, especially regarding luteifrons and also trans-Andean

birds vs. the rest. But the variation in any one group does muddy the picture

significantly. That said, I don't particularly see that as a mark against a

split. Philadelphia and Red-eyed vireos songs are often completely

indistinguishable by anyone (including themselves), and others like some

members of the former Solitary Vireo differ mostly in average characters

somewhat like these greenlets. Conversely, vocal differences by themselves

aren't going to persuade me to split these or other Vireonidae, given

dialectical differences in other members of the family that (in my

opinion) aren't indicative of separate species status. Calls may well be a

better avenue to show speciation here, but even if they eventually prove to not

be that different I still think my points above stand.

“It's

those average differences combined with the other evidence presented persuades

me to still vote for the split. I understand Dan's point that this has some

aspects of "doesn’t really feel like it is cooked enough", to use his

terminology. But I do think that the four species interpretation is a step

forward in our understanding of the complex, and in my opinion at least, a

significant step forward.”

Comments

from Mario Cohn-Haft (who has Del-Rio vote): “YES. I basically agree with everybody

else (the nays and yays). Here in the central Amazon,

it's really obvious that there are consistently distinct voices and plumages

across the rios Negro and Madeira and lower Amazon,

and seemingly across the Tapajos as well. So, the 4-way split proposed is, I would say,

a conservative description of reality (there are probably more than 4 spp.

involved) and a perfectly reasonable conclusion from the point of view of

nomenclature and distributions.

“On

the other hand, the story as published leaves a lot to be desired in the way of

convincing evidence. That is, I'm more convinced by my own experience

than by what's available in the literature. And I think the reason for that is that a

proper vocal analysis requires a lot more work and thought than anybody has

been willing to give it so far. I'm the first to admit that I didn't tackle the

problem myself out of sheer laziness. Way back in the late 80s when Ridgely's

frustratingly erroneous description of the situation irked me into actually

thinking about doing something, I realized what a big job it was going to be,

and I've sat around hoping someone would do it up right ever since. Yes, some populations can produce

vocalizations just like others, making 100% diagnosis on one character alone

difficult. So what? (Ah, and guess what, that happens with

suboscines too.) A good vocal analysis needs to take into account repertoire,

context of vocalizations, frequency (not kHz, but opposite of rarity--the number

of times that a particular vocalization is given); carefully chosen vocal

variables (not a universal recipe of maxs, mins,

etc.-- I could go on and on about what good vocal variables are, but this isn't

the place) and comparison of analogous vocalizations, not just everything at

random; means and variances, for example, only make sense in these specific

contexts. What we're seeing consistently nowadays are molecular studies to

which vocal or morphological components are added almost as an afterthought to

"strengthen" (or not) the molecular conclusion, but that do not stand

on their own. In that sense I totally agree with Dan and others who say this

cake is only half-baked at best. (By the way, I can't remember if iris color

entered into any of this, but it's also a relevant diagnostic character in this

complex.)

“The

hard question for me is: How purist (perfectionist?) are we going to be? I

think the 4-spp answer is right (and an underestimate), so how much longer will

we wait before it makes it into the checklist? If we were Peters, or better yet

my hero John Zimmer, we'd just declare it and be done with it and let

nay-sayers or future generations of topic-challenged grad students worry about

the details. And that's what I'm inclined to do. I vote YES, believing it's the correct answer,

while recognizing that the published and available evidence don't tell a

thoroughly convincing story. Messy? A bit authoritative or arbitrary? Sorry.

Watching the planet burn, flood, become bare of vegetation at the rate it is

now, I find it hard to justify waiting to do up properly the taxonomy of what I

used to hold aside as "my pristine Amazon". We are literally on the

brink of cataloging extinct species.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“YES. A complicated one

indeed. The depth of the genetic splits

here are impressive, and combined with some average differences in plumage,

iris color, and vocalizations, even in the apparent absence of diagnosability,

are enough to sway me. As Andrew and

Alvaro both note, songs of some accepted species pairs of vireos (Red-eyed vs.

Philadelphia; all 3 of the splits from former “Solitary” Vireo) are doubtfully

diagnostic. I will say, that without

having ever conducted anything approaching a quantitative analysis, I’ve long

been struck by apparent vocal differences corresponding to each of these

suggested four species. I agree with

Mark that some populations can give either 1 or 2-note songs, and that they are

all broadly similar in quality, but nonetheless, I can still hear qualitative

differences in inflection and pitch.

Granted, these may not hold up to broad geographic sampling of each

population, but, at least in my coarse-grained field experience with this

group, it has always been my impression that there were some pretty consistent

geographic differences in songs that correspond pretty well to the partitioning

suggested by the genetic data. The case

is a long way from perfect, but I would agree with Andrew that this represents

a step forward in our understanding, and I think the genetic data combined with

the sum of mean differences in various character states is enough to hang our

hats on.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“YES. Although the plumage differences are not entirely diagnosable, and the

song data are limited and substantially overlapping, neither type of character

alone is expected to be diagnostic for this group. However, the molecular

divergences, even if based only on mitochondrial DNA, are impressive.”

Additional

comments from Robbins:

“Given that the vast majority supported recognition of the 4 way split, I will

shift my on the fence vote to a YES.”

Comments

from Naka:

“YES. As far as I understand it, the 4-spp split fixes most problems from the

Brazilian Amazon, particularly within the Guiana Shield, where luteifrons

and ferrugineifrons replace one another. Along the Rio Branco suture

zone, birds are genetically, vocally, and morphologically distinct, which

includes a pale iris in ferrugineifrons, as Mario mentioned on his vote.

So, despite some concerns, I agree with Kevin in that those split populations

have always looked and sounded different to me.”