Proposal (1009) to South

American Classification Committee

Treat Amazona

autumnalis (Red-lored Parrot) as consisting of three species

Note:

This is a high-priority issue for WGAC.

Background: Our current Note reads as follows:

34c. The Ecuadorian subspecies lilacina

and the Brazilian subspecies diadema were formerly (e.g., Cory 1918, Pinto 1937) considered separate species

from Amazona autumnalis, but Peters (1937) treated them as

conspecific. Ridgely & Greenfield (2001) treated diadema as a

separate species but did not provide justification. Del Hoyo & Collar (2014) treated both lilacina (“Lilacine

Amazon”) and diadema (“Diademed Amazon”) as separate species based on

differences in plumage and bare parts coloration, and this was further

supported by qualitative inspection of specimens by Donegan et al. (2016). Smith et al. (2023) found a deep genetic

divergence between autumnalis s.s. and diadema. SACC proposal needed.

The

status quo, maintained in most classifications (e.g. Dickinson & Remsen

2013), is that this species consists of 4 subspecies:

1. A. a. autumnalis from Mexico to N.

Nicaragua

2. A. a. salvini from Nicaragua to the

Chocó of sw. Colombia and also to n. Venezuela.

3. A. l. lilacina: endemic to the Chocó

of w. Ecuador

4. A. a. diadema: disjunctly in central Amazonian

Brazil along the Amazon and lower Rio Negro.

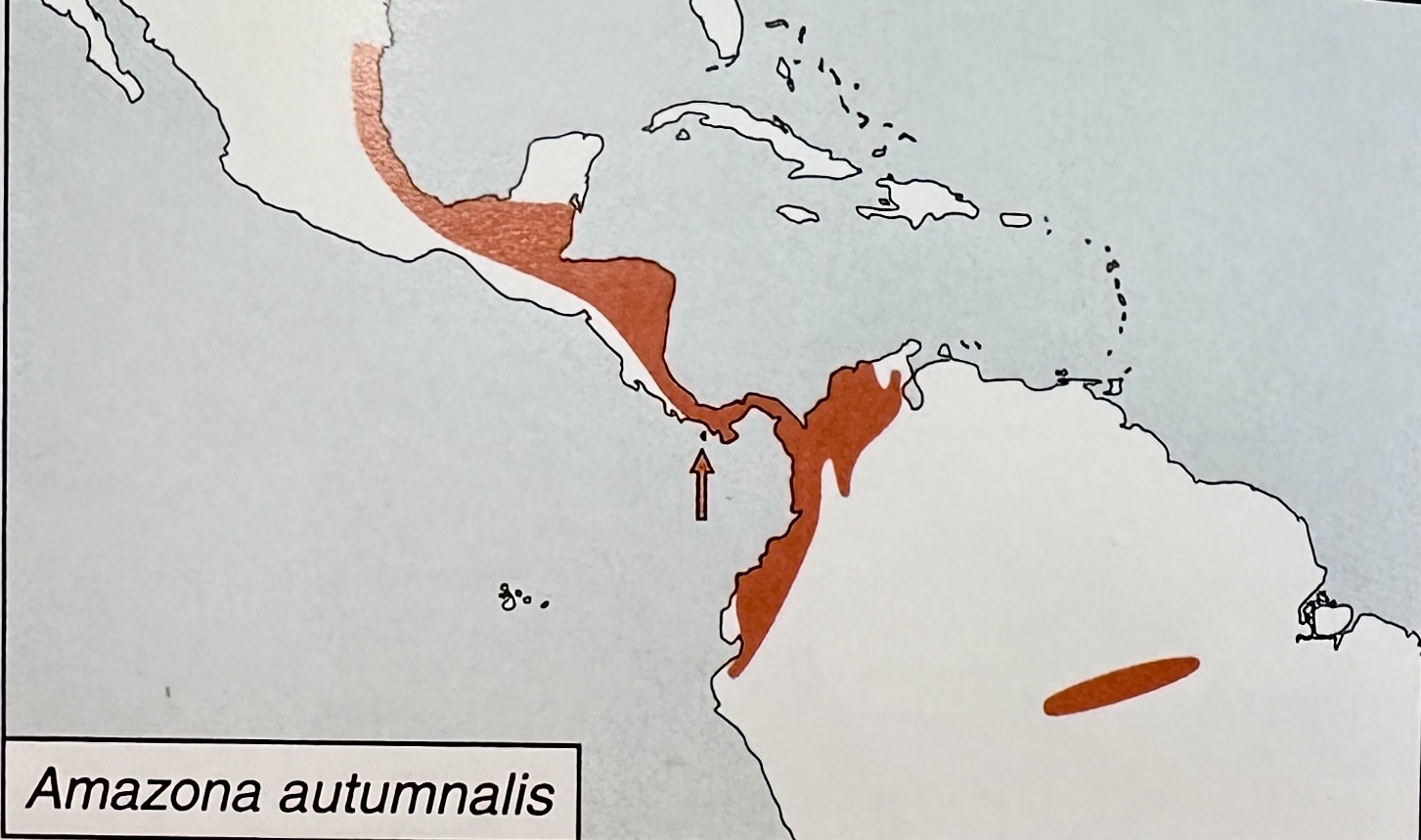

Here

is the composite distribution map from Forshaw (2006:”Parrots of the World”):

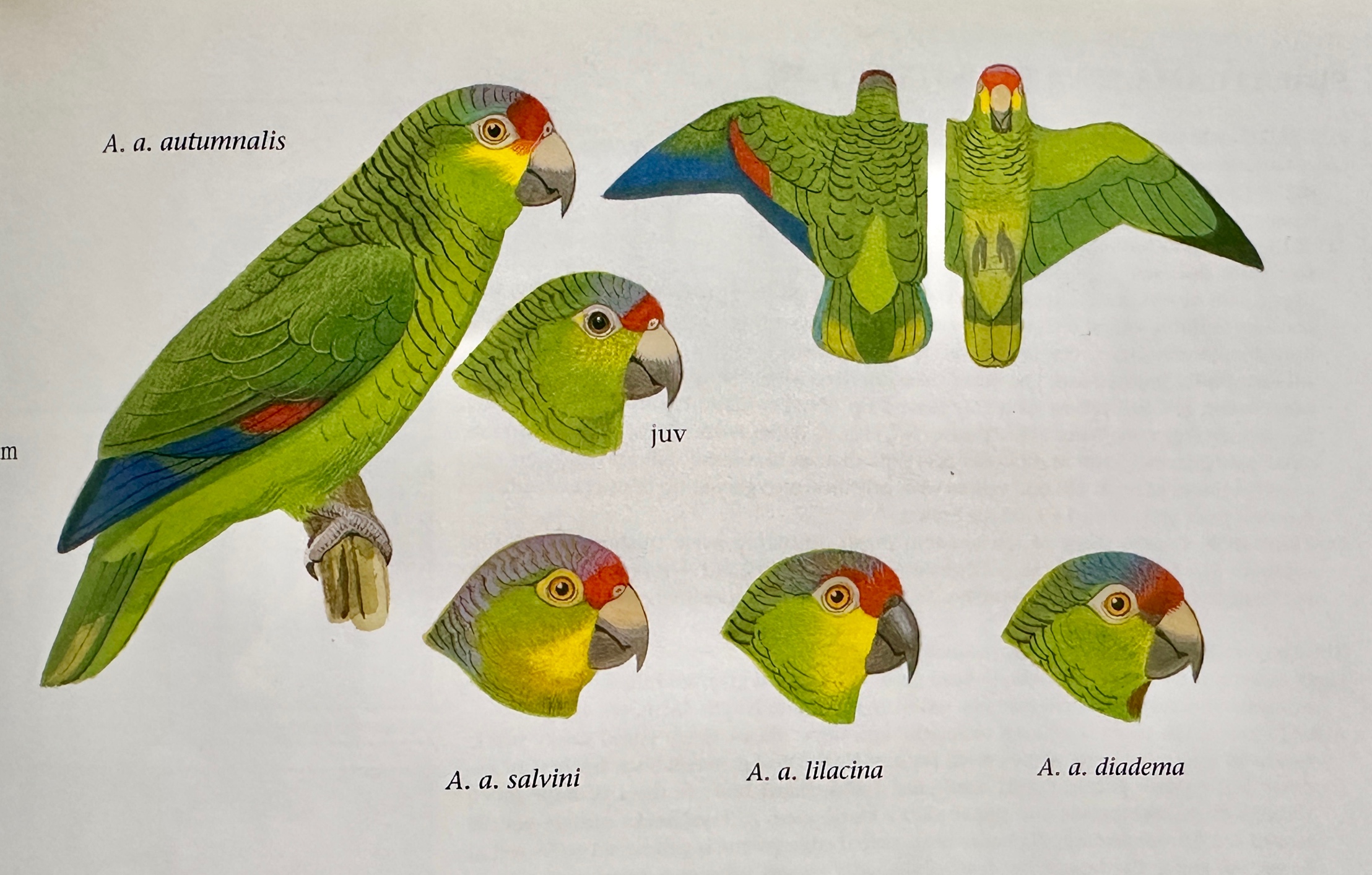

Here

is the plate by Frank Night from Forshaw (2006:”Parrots of the World”):

A.

l. salvini

apparently has a zone of intergradation with A. a. autumnalis.

Here’s

the plate in del Hoyo & Collar (2014) by Ångels Julglar:

Here

are three photos from Macaulay, L to R, nominate autumnalis pair (by

John Doty), lilacina (by Edison Buenaño), diadema

(by Héctor Bottai):

New

information:

Del Hoyo & Collar (2014) treated lilacina

and diadema as species separate from autumnalis. Here is the HBW rationale (provided by Pam

Rasmussen):

For

diadema:

“Usually

considered conspecific with A. autumnalis and A. lilacina, but

differs from lilacina in certain characters outlined under that species, and

from both in its nares being covered in red feathers, with rest of red patch on

face sharply delineated to form a distinct rectangle, quite different from

shape of red patches on other taxa in complex, and allowing blue on crown to

extend forward to border the frons (3); powdery dorsum, resembling more that of

A. farinosa (1); bill black but with pale patch below nares (2); head

much flatter and longer in lateral profile (mensural score 1). Monotypic.”

For

lilacina:

“Usually

considered conspecific with A. autumnalis and A. diadema, but

differs in its all-black upper mandible (2); red of forecrown continuing over

eye (2); lilac of crown not extending onto nape (2); paler, clearer green cheek

(ns[1]); possibly no red on chin (ns[1]); narrow, sharp yellow edges of

wing-coverts and flight-feathers (ns[1]); retiring, non-aggressive behaviour (quite different at least from autumnalis (1) )

(ns[1]); smaller bill (tiny museum sample size supplemented by photographs; 1).

Specific status considered appropriate also in unpublished recent taxonomic

study (2). Monotypic.”

Donegan

et al. (2016) evaluated the del Hoyo & Collar taxonomy with respect to how

this affected the Colombian bird list.

They also provided photos of 5 specimens

from AMNH. Here is what they wrote:

“We concur that A. lilacina is

a quite different bird from both diadema and autumnalis (Fig.

15). It has virtually no blue on the crown but extensive yellowish-green

plumage on the face and throat, carpal edgings and vent and a dark bill.

“The split of diadema from autumnalis

is less clear-cut. The more extensive blue scaling on the mantle of diadema

is a noteworthy feature (Fig. 15), but the head patterning and overall

coloration is more similar to autumnalis. The difference in nare feathering can be seen in online photographs of live

birds but was not obvious in specimens we inspected. Differences in the shape

of the red patch on the lores are less impressive when one considers variation

in this feature both within autumnalis and between the nominate

subspecies and salvini. It is not necessary for us to express any view

on the rank of diadema, as it is extralimital as regards Colombia.”

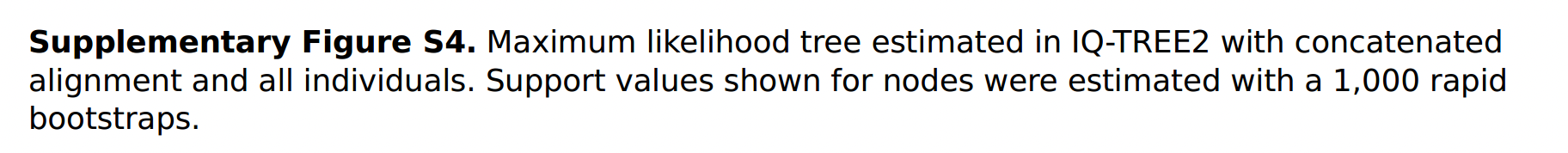

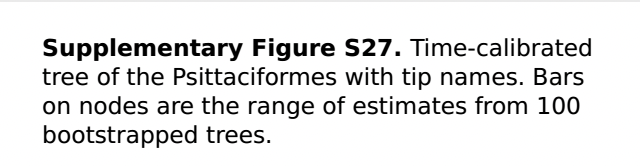

Smith

et al. (2023) did not sample lilacina, but they had diadema in

their tree. It comes out as sister to autumnalis

in their analyses, but the divergence is deeper than that among many taxa

ranked as species in Amazona. In

S27, my eyeball extrapolation down to the X-axis suggests the node that joins autumnalis

and diadema is ca. 3 MYA.

Voting: Let’s do it this way:

YES = Treat lilacina and diadema as

separate species from A. autumnalis.

NO = maintain status quo OR treat either lilacina

or diadema as a separate species but not both.

Discussion

and recommendation:

I’m not going to vote until I see what others say, but I’m leaning towards a

YES for the following reasons. First,

that deep genetic split is impressive. I

don’t support using genetic distance of neutral loci as a metric for assigning

species rank, but this looks like an extreme case, with diadema more

divergent from autumnalis than are many sister taxa treated as species

in Amazona. As for lilacina,

available evidence suggest an abrupt change from A. a. salvini in

Colombia to lilacina in Ecuador, or perhaps this should be phrased to

indicate that there is currently no evidence for gene flow in these parapatric

taxa. If that is really the case, then

species rank is required. Finally,

Peters provided no rationale for the lump, nor has anyone subsequently.

However, here’s what makes me

wonder. The large distance between diadema

and the closest autumnalis populations suggests a long period of

isolation, unlike many sister parrot species, so perhaps that genetic distance

is just the long accumulation of “irrelevant” neutral mutations. The absence of genetic samples of lilacina

is unfortunate – that’s a case in which genetic data really would illuminate

species limits because of the apparent parapatry: other than some governmental

border posts, there is no substantial barrier to gene flow between the

two. As noted by Donegan et al. (2016)

an argument can be made that diadema looks more like autumnalis

than lilacina does. Also, what is

really known about the potential contact zone between autumnalis and lilacina? There do not seem to be many specimens of lilacina

in collections, but it looks to me as if careful photographic sampling of

individuals might hold promise for at least a preliminary assessment of the

contact zone using bill color and head pattern.

As for plumage …. I’m still trying to

reconcile why the specimens shown in Donegan et al. show what I would consider

“important” differences, as reflected in del Hoyo & Collar’s description,

in contrast to my impressions from the photos of living birds, the signal from

which I perceive is dominated by similarities, as in the two plates. Also note the differences between the two

individual autumnalis in the photos – this is almost certainly a mated

pair. How much individual variation is

there? So, I don’t know what to make of

the differences in head plumage. All

this makes me want to demand an actual formal analysis of plumage characters,

with specimen N and locality data reported, before taking the plumage into account. Evaluating N=1 samples of specimen photos,

live bird photos, and artists plates is not the way science should be

conducted. Finally, as for Peters, those

of us who use the Cory-Hellmayr series know that Cory’s early, single-authored

volumes (1918, 1919) made few changes in taxon rank

from the original ODs unless Ridgway or someone else had already done it; not

until Hellmayr joined the project was more critical thinking applied to lumps

and splits.

And then there is the absence of vocal

data. This is tough to analyze in

parrots for obvious reasons, but at the least flight calls seem to be fairly

stereotyped and a good marker for species differences in sympatric congeners.

English

names: If the proposal passes, then I see no need

for a separate proposal on English names given that Lilacine

and Diademed have been used extensively (Diademed even goes back to Cory

1918). If anyone objects, please speak

out.

References:

DONEGAN, T., J. C. VERHELST, T. ELLERY, O. CORTES-HERRERA, AND P.

SALAMAN. 2016. Revision of the status of bird species

occurring or reported in Colombia 2016 and assessment of BirdLife

International's new parrot taxonomy. Conservación Colombiana 24: 12–36.

SMITH, B. T., J. MERWIN, K. L. PROVOST, G. THOM, R.

T. BRUMFIELD, M. FERREIRA, W. M. MAUCK III, R. G. MOYLE, T. F. WRIGHT, AND L.

JOSEPH. 2023. Phylogenomic analysis of the parrots of the

world distinguishes artifactual from biological sources of gene tree

discordance. Systematic Biology 72: 228-241.

Van Remsen, June 2024

Comments

from Robbins:

“NO. Because of the lack of genetic data for lilacina coupled with what

Van points out as potential variation in head pattern (plumage, soft part

coloration), for now I vote NO until some of these issues are addressed.”

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“YES – I tis a patchwork of information here, that I am using. First large

divergence time with diadema based on molecular data. Then lilacina

is quite different in appearance and appears to be essentially parapatric with autumnalis.

That is interesting. I tis piecemeal, and patchwork but I think the three species

theory will be what will prevail over time, as more data is gathered.”

Comments from Areta: “I vote NO to the split

of lilacina. I am unimpressed by the

differences between the different populations in terms of genetic and plumage,

which seem on par with those between several populations of other Amazona taxa.

For example, I myself have studied and published on the sierran populations of Amazona aestiva, which lack any red or

yellow in the "shoulder", no yellow on the face, and a different

green colour despite the close proximity to typical xanthopteryx populations (Areta 2007).

“Terry

Chesser suggested that the deep branch between lilacina and autumnalis

in Smith et al. might be due to missing data (as these taxa are in the upper

10% of missing data taxa).

“In

a PhD thesis (Pilgrim 2010, courtesy Paul F. Donald) the genetic data (883bp of

ND2) tells a different story:

"Table 4.2. The average p-distances between the subspecies

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

1 |

A. a. lilacina.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

A. a. salvini |

0.012 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

A.a.autumnalis |

0.023 |

0.026 |

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

A.a. diadema |

0.011 |

0.000 |

0.025 |

|

|

|

|

5 |

A. viridigenalis |

0.053 |

0.026 |

0.057 |

0.057 |

|

|

|

6 |

A.leucocephala |

0.177 |

0.171 |

0.152 |

0.169 |

0.197 |

|

|

7 |

Pionus

maximiliani |

0.369 |

0.381 |

0.341 |

0.376 |

0.336 |

0.353 |

|

Table 4.2. Estimates of Average Evolutionary

Divergence over Sequence Pairs between Groups. |

“The divergence of A. a. lilacina from A. a.

salvini is 1.2% and divergence of A.

a. lilacina from A. a. autumnalis

is 2.3%.

A. a. diadema shows no divergence from A. a. salvini. The A. a.

autumnalis group shows a divergence from A. viridigenalis of between 2.6 to 5.7% and a divergence from A. leucocephala from Cuba of between

15.2 to 19.7%."

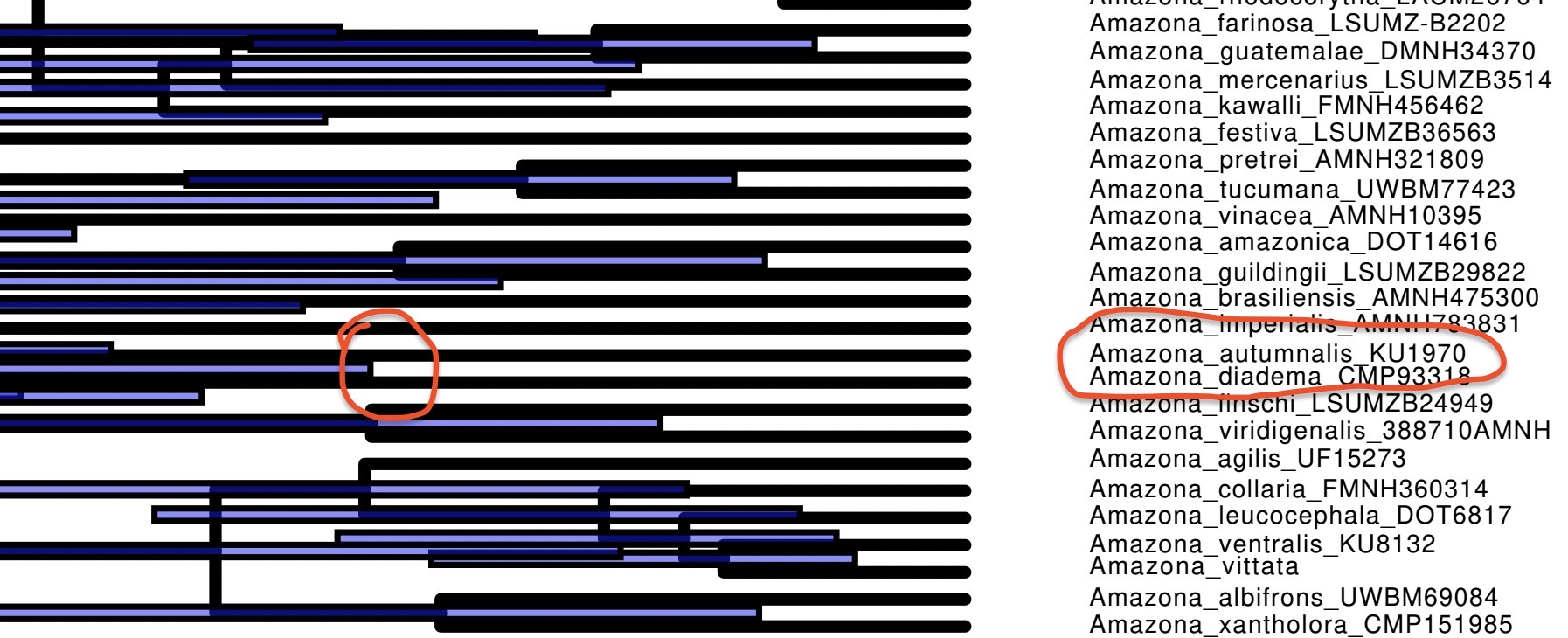

“And using the same molecular ND2 dataset,

Pilgrim obtained the following MP consensus tree:

“Pilgrim also reports on the smaller bill of lilacina, and mentions lack of sexual dimorphism in lilacina (as a difference between the

size-dimorphism in other autumnalis

taxa, and Amazona in general).

“A paragraph on geographic

variation in plumage is worth quoting in full:

"The A. autumnalis specimens from the Natural

History Museum at Tring are arranged taxonomically and by country of origin.

While examining these to examine putative differences in area of plumage color

between the subspecies, it was noted that the amount of yellow on the cheeks of

A. a. autumnalis, the feature which gives this parrot its common name of

Yellow–cheeked Amazon, gradually decreases in size from the northern Mexican

specimens with a very large bright yellow cheek patch, to specimens which have

a very small patch of yellow feathers on the cheeks in the south of its range. A.

a. salvini has no yellow in the cheeks. It was not possible to assign some

specimens that had merely a single fleck of yellow on the cheeks to either A.

a. salvini or A. a. autumnalis. These intermediate specimens

originate from Honduras and Nicaragua, an area between the ranges of A. a.

autumnalis and A. a. salvini (Fig. 1.00), and may be subspecific

hybrids as reported by Howell

(1957). No such

intermediate forms between A. a. lilacina and A. a. salvini have

been observed either in the museum specimens or amongst the dozens of wild

captured living specimens observed during my role as European studbook keeper

for A. a. lilacina. This suggests an absence of a hybrid zone between A. a. lilacina and A. a. salvini. However, a survey of the area where the ranges of

these subspecies meet on the border of Ecuador and Colombia would be required

to ascertain this with any certainty. As mentioned in the introduction Olivares (1957) suggests the possibility

of hybridisation but presents no evidence for it. There are no other or more

recent reports of a hybrid zone between A.

a. lilacina and A. a. salvini in

the literature. A. a. diadema has an

allopatric range."

“Areta, J.I. 2007. A

green-shouldered variant of the Turquoise-fronted Amazon Amazona aestiva from the Sierra de Santa Bárbara, north-west

Argentina. Cotinga 27: 71-73

Pilgrim, M.A., 2010, An

investigation into the taxonomic status of Amazona

autumnalis lilacina using a multidisciplinary approach. PhD thesis,

Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool, UK.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“NO. The data are just too patchy and inconsistent, and it would seem that more

intrapopulation variation in plumage might exist as well; clearly more

thorough, quantitative data on plumage and genetics are needed.”

Comments

from Lane:

“NO. This is a project or two that might benefit greatly from directed

investigation into the relationships of these three groups of taxa. I suspect

both lilacina and diadema will prove to be species-level with

respect to the autumnalis group, but for now we have missing

information.”

Comments

from Claramunt:

“YES. Going on a limb in this case and I agree that

it would be better to have more detailed analyses but at least lilacina looks like a

well-delineated taxon. I don’t see any signs of intergradation in photos from W

Ecuador. The case of diadema is harder because the bird is remotely allopatric and the

diagnostic traits may be just too subtle, but I think it is correct that the

exact shape of the loral/frontal patch is diagnostic, ending in an abrupt

transition to a pure green supercilium in diadema rather than a

diffusing over the eye like in autumnalis. That, plus

the considerable genetic divergence convinced me that we need to revert the

unexplained lumping made by Peters et al.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“YES. I will admit up front to not

having any experience with lilacina, so the lack of any genetic data for

the latter taxon is vexing, because it doesn’t leave me a lot to go on. I will say, as others have suggested, that

the variation in the amount of yellow in the face doesn’t impress me either –

other Amazona species (amazonica and, especially, aestiva come

quickly to mind) exhibit tremendous individual variation in the amount and

distribution of yellow on the head and face, even within the same population,

and I suspect at least some of this variation is attributable to age. However, I am struck by the fact that, as Van

states, lilacina and salvini have seemingly parapatric

distributions with respect to one another, with no obvious geographic barrier

separating them, and yet, there’s no obvious intergradation, and the respective

phenotypes seem to be maintained. That,

combined with the fact that this is yet another case of a pair of taxa that

were described as distinct species, and then lumped without rationale provided

by Peters, are enough to tilt me in favor of treating them as distinct

species. As for diadema, I feel

on firmer ground in voting for a split on this one. We do have indication of a deep genetic split

on this one, and even though Van’s caveat regarding the possibility of long

isolation just reflecting the accumulation of irrelevant neutral mutations is

well taken, I’ve always felt that diadema was a different beast. I had a lot of experience with autumnalis

in Mexico, Panama, and Costa Rica before I first encountered diadema on

my first visit to Manaus, and I remember being struck by how different it

looked (particularly the farinosa-like abundant powder-down on the

dorsum and different distribution of red and blue on the head, not to mention

the absence of yellow in the face) and sounded.

To me, the flight calls of diadema and autumnalis are

pretty different. I haven’t heard the

songs of either taxon much in recent years, so I’m a little rusty on those, but

the flight calls are what you hear mostly, and my impression of those has

always been that they are distinct. So

to me, if you’ve got two taxa that differ in some aspects of plumage, differ in

at least some vocal characters, and have a deep genetic split relative to other

recognized species-pairs in the same genus, and are clearly on independent

evolutionary trajectories given their extremely allopatric distributions, it

doesn’t really matter whether the depth of the genetic split is largely due to

accumulation of irrelevant neutral mutations or not – they already look and

sound consistently different, and they aren’t going to be sharing genetic

material anytime in the foreseeable future (= ever), so why not revert to the

pre-Peters treatment as distinct species?”

Comments

from Del-Rio:

“NO: Given the limited genetic data available on lilacina, I believe

that future research could potentially reveal that these are all distinct taxa.

However, for the time being, I will adopt a conservative approach. Again, an

interesting system to track different patterns of accumulation of

psittacofulvin in Psittacidae populations living in different environments.”

Additional

comments from Stiles:

“Given Kevin´s comments and reconsidering the information in the BMNH paragraph

as well as other data mentioned by Pilgrim in particular, I am willing to

change my vote to a YES for recognizing lilacina and diadema as

separate species from autumnalis. The case for diadema seems

especially clear for species status given the deep genetic difference, the

morphological and apparent vocal differences and its widely divergent

distribution. The case for species status of lilacina is somewhat less

clear, but given the differences in plumage and bill colors. overall size and

lack of sexual size dimorphism and the lack of any intermediate specimens (of

many examined) I think that this tips the balance toward at least tentatively

considering species status (especially because Peters did not give any real

evidence for lumping them, The lack of specimens (or observations) in the

potential contact zone could be interpreted simply as missing evidence, but on

the other hand, it could indicate that there IS no contact, with lilacina

thus considered as a peripheral isolate from autumnalis which as such evolved a suite of phenotypic differences

(often the case in such situations).”

Comments

from Remsen:

“YES. After letting this incubate for

months. First, Kevin’s comments are

persuasive, even though the data on flight calls are not published. As for the genetic data, I don’t think we can

rely on the unpublished Pilgrim data, which claim that autumnalis and diadema

are identical at those loci. Given the

vast geographic distance between the two and the plumage differences, I think

something must be amiss with those data, or at least they should be repeated. The data of Smith et al. ARE published, and although the branch length might be

exaggerated by missing data, they are not identical. As for lilacina, yes the contact zone

if there is one is not sampled but I think the absence of any signal of gene

flow with the data at hand puts burden-of-proof on treating them as

conspecific. This is a tough call and a

data-deficient case, for sure, but with considerable trepidation, I think what

we have available suggests separate species.”

Comments

from Mario Cohn-Haft (voting for Bonaccorso): “YES. Full disclosure: I know only diadema

in the field. that makes my personal experience with the complex pretty well

useless. However, when has that kept me from offering an opinion? All my

instincts say that diadema must be a distinct species from the rest:

it's very distantly isolated geographically in the central Amazon from all the

others, which are trans-Andean and more or less continuous in distribution; it

has no yellow on the face but often does have yellow on the crown, both of

which seem intuitively like important differences; also has what strikes me as

a wider, more conspicuous bare eyering than the others, more and different blue

on the crown; and finally it has an unusual and mysterious life-history,

apparently involving an intra-Amazonian migration, such that I'm not sure we

even know where it breeds! See below for

a few pictures of diadema from Manaus. So, if there were no genetic data, I'd vote

for recognizing diadema as a full species and would more or less

instinctively visualize the other 3 as geographic variants of a single species,

considering their seemingly continuous distribution. However, the fact that experienced folks (and

the pictures) suggest that lilacina too is different might convince me

to vote "yes" overall.

“However,

there ARE genetic data. The study showing diadema to be strongly

different from autumnalis jibes with the plumage and biogeographic

arguments laid out above and is intuitively satisfying. The Pilgrim study that

includes lilacina and finds all 4 taxa to be between 1-2.5% different

from one another, except diadema which is genetically identical to salvini,

makes no sense at all, and I'm inclined to follow Van's lead and just assume

it's wrong. Not a very satisfying conclusion, i recognize, but seemingly

advisable given the rest of the evidence.

“I

was about to wimp out and vote "no" because of the incomplete and

conflicting genetic data and in recognition that i don't feel like i can say

anything first-hand about lilacina. But then i reread the intro to

the proposal and remembered that the only reason we're even talking about this

is because of Peters' lumping without explanation (as usual). So, really,

the whole thing is quite simple: ignore Peters and vote YES in

recognition of what was right from the start and never should have been

changed.”