Proposal (1010) to South

American Classification Committee

Treat Cranioleuca

marcapatae weskei as a species

Note:

This is a high-priority issue for WGAC.

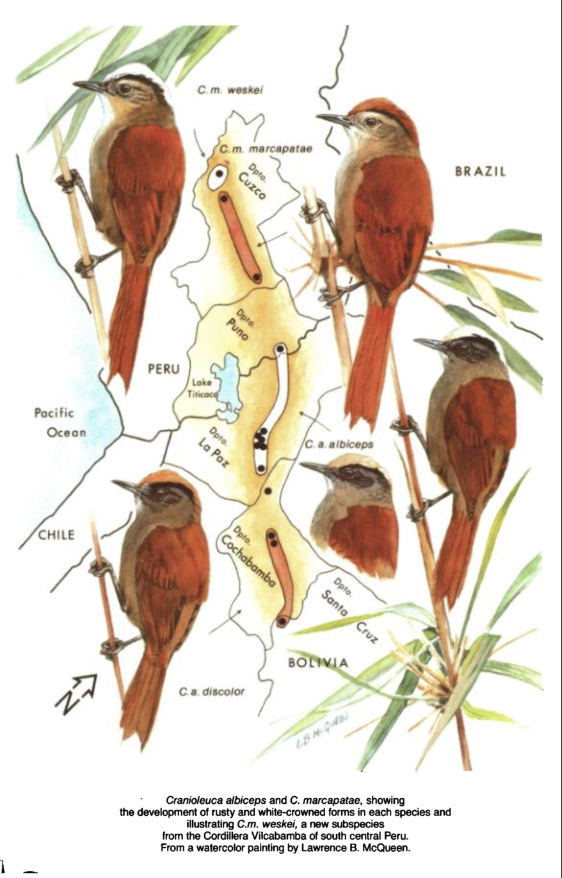

Background: I (Remsen 1984) described weskei

as an isolated subspecies of nearby ecological equivalent Cranioleuca marcapatae,

based on their conspicuous differences in crown color. The rationale for subspecies rank was based

in part by extrapolation to the situation in Cranioleuca albiceps, in

which (1) the nominate subspecies shows individual variation in crown color

from white to ochraceous, with white-crowned individuals looking superficially

like weskei (to the point that Vaurie [1980] considered them to

represent an isolated population of C. albiceps, although I regard that

as a lapsus), and (2) the Cochabamba subspecies discolor has no white in

the crown. The basic logic was that if

crown color can vary dramatically within individuals of a single taxon as well

as between taxa currently treated as subspecies, then weskei should also

be treated at the subspecies rank.

Here

is the plate from the OD (by Larry McQueen):

Here

are some specimen from LSUMZ. I don’t

think any of the specimens from dpto. La Paz are as ochraceous as those of C.

a. discolor. Note the crown color of

marcapatae differs from any of the others and matches the back color, unlike

any of the others, including weskei. We don’t know (yet) whether the

tawny crowns in nominate albiceps are a consequence of gene flow:

We

do not have a SACC Note on weskei.

What we do have is the following (which needs to be updated with respect

to this proposal; although I have completed adding SACC notes on del Hoyo &

Collar [2014; nonpasserines], I stalled out somewhere in the suboscines on the

passerine volume [2016]:

49. The superspecies relationship proposed for Cranioleuca marcapatae

and C. albiceps (e.g., Remsen 1984) is corroborated by genetic

data (García-Moreno et al. 1999b, Derryberry et al. 2011); Fjeldså & Krabbe

(1990) proposed that they might be best treated as conspecific.

Here’s

how I set up the taxonomic problems posed by this complex:

“Should

each of the four spinetail taxa in question be considered allospecies of a

superspecies complex, subspecies of a single biological species, or some

intermediate combination? In the absence of comparative data on vocalizations

and other potential reproductive isolating mechanisms or on degree of genetic

differentiation, any taxonomic decisions at this point for these primarily

allopatric populations are tentative at best.”

Concerning

the crown color differences, here is what I wrote:

“Current

information indicates that crown color differences do not necessarily result in

reproductive isolation. Specimens from an area (Choro, Prov. Ayopaya, Dpto.

Cochabamba) geographically intermediate between populations of C. a.

albiceps and C. a. discolor are intermediate in crown color between

the white-crowned nominate subspecies and tawny-crowned discolor.

Furthermore, the high frequency of buff-crowned individuals in the Dpto. La Paz

population (see below) may indicate gene flow from the southern populations.

Thus it seems best to disregard crown color, the character that varies most

dramatically among populations, as a potential isolating mechanism (although

this conclusion is based on the assumption that the populations are in

secondary contact). Therefore, that marcapatae

has a chestnut crown, in contrast to neighboring weskei and albiceps,

in itself provides no evidence for reproductive isolation.”

I

went on to conclude that changing currently recognized species limits was

unwarranted given the lack of critical data.

New

information:

Del Hoyo & Collar (2014) treated marcapatae

as a separate species based on the Tobias et al. point scheme as follows (provided

by Pam Rasmussen):

“Hitherto

treated as conspecific with C. marcapatae, but differs in its white

crown (3); stronger black lateral crownstripe (1); and much more evenly

delivered song, shorter in length (2), faster (at least 2), lower maximum

frequency (ns[2]), and different note shape (ns[at least 1]) (1). Monotypic.”

This

is a good example of the conceptual flaws of the Tobias et al. scheme, namely

that the scores are derived independent of phylogeny. In this case, we already know in sister taxa

that crown color is not associated with a barrier to gene flow, yet here it is

accorded 3 points out of the 7 needed for species rank.

The

vocal data are from Boesman (2016i), who analyzed 7

recordings of weskei and 9 of marcapatae:

“Song of weskei

differs from marcapatae

by much more uniform delivery, shorter length (score=2), lower max. frequency

(score=2), faster pace (score=2 or 3), descending song strophe (vs. rising and

falling, score 2) and different note shape (score 1). This would lead to a

total vocal score of 4 or 5 when applying Tobias criteria.”

On

the surface, these sound like impressive differences. I am assuming that the recordings represent

different individuals, but I leave it to those more experienced with Cranioleuca

voices to evaluate them.

As

for the inevitable demand for genetic data, I continue to point out their

limited utility for assigning taxon rank in cases like this, i.e. allopatric

taxa in a monophyletic group. We

already know what the results would be – the populations WILL differ,

especially given the obvious phenotypic differences. So, how different do they have to be to be

treated as species? Genetic data measure largely neutral loci not explicitly

those genes associated with gene flow and reproductive isolation, and thus

largely measure time-since-isolation and effective population size. The former is very roughly correlated with

speciation, but we have concrete examples of dramatic differences in genetic

distance among populations that are given different taxonomic ranks that no one

would dispute (e.g. capuchino Sporophila seedeater species vs. Syndactylus

bulbul populations that are phenotypically indistinguishable and not accorded

any taxonomic rank) that provide evidence that characters associated with

reproductive isolation do not evolve at a steady rate but instead

idiosyncratically. Looking at branch

lengths among close relatives eliminates some but not all of the problems. Anyway, see the SACC note on earlier genetic

studies that only show that we’re dealing with a monophyletic group, although weskei

to my knowledge has yet to be sampled.

Here

is the tree from Harvey et al. (2020), which shows clearly that albiceps

s.l. and marcapatae are sister taxa and that the node that unites them

is as deep as those linking most Cranioleuca treated as species, thus in

the crude comparative sense supporting species rank for them.

As

for evidence for or against gene flow between marcapatae and weskei,

these are strongly allopatric taxa. The

aerial distance on the map between the Vilcabamba range and the main Andes

might not be impressive to those not familiar with the area, but the ecological

gap is huge for high-elevation cloud-forest birds whose short, rounded wings

predict limited dispersal abilities.

Although in my opinion the dispersal ability of nonmigratory birds is

vastly underappreciated, nonetheless, I suspect that it would be so infrequent

between these two as to be impractical to detect without massive sampling.

Recommendation: Given my involvement

with these taxa, I think the right thing to do is recuse myself from voting,

and so I have no recommendation, and Glenn Seeholzer, whose dissertation was on

the Cranioleuca antisiensis group (e.g. Seeholzer & Brumfield 2018),

has agreed to take my voting slot. I

don’t have strong feelings either way at this point – I can see both sides.

English

names: If the proposal passes, then I see no need

for a separate proposal. This taxon has

no phenotypic features that distinguish it uniquely from other Cranioleuca,

and so Vilcabamba Spinetail seems not only the obvious choice but the only

one. Of course, if you see it otherwise,

please speak out and do a proposal.

References: (see SACC

Bibliography

for standard references)

BOESMAN, P.

2016i. Notes on the vocalizations

of Marcapata Spinetail (Cranioleuca

marcapatae). HBW Alive Ornithological Note 100. In: Handbook of the

Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow-on.100100

REMSEN, J. V., JR. 1984. Geographic variation, zoogeography, and

possible rapid evolution in some Cranioleuca spinetails (Furnariidae) of

the Andes. Wilson Bulletin 96:

515-523.

SEEHOLZER, AND

R. T. BRUMFIELD. 2018. Isolation by

distance, not incipient ecological speciation, explains genetic differentiation

in an Andean songbird (Aves: Furnariidae: Cranioleuca

antisiensis, Line-cheeked Spinetail) despite near threefold body size

change across an environmental gradient.

Molecular Ecology 27: 279-296.

VAURIE, C. 1980. Taxonomy and

geographical distribution of the Furnariidae (Aves, Passeriformes). Bulletin American Museum of Natural History

166: 1-357.

Van Remsen, June 2024

Vote tracking chart:

https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart968-1043.htm

Comments

from Robbins:

“As far as new data, in my opinion, only the vocal data are potentially

relevant. Listening to vocalizations I think Boesman accurately describes

differences, but whether these mean anything who knows. I’m going to wait and

see what Glenn has to say on this given his deeper perspective on Cranioleuca

before I vote.”

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“NO for now, will wait until Glen Seeholzer gives and

opinion, I am open to change.”

Comments

from Lane:

“NO. This is a case that I think is a bit hobbled by

limited information. The distribution of the taxon weskei is still

largely thought to be solely in the Vilcabamba range of Cusco and Junin depts,

but since the 00's, it's been known that birds with white crowns occur all the

way to the north side of the Mantaro valley in Junin dept. This is the

population that I believe the recordings used in Boesman's assessment are from

<https://xeno-canto.org/species/Cranioleuca-marcapatae?query=ssp:%22weskei%22>. A

confounding factor is that there seems to be a vocal shift *within*

white-crowned birds across the Mantaro, as birds I recorded in 2010 in

Huancavelica dept (south of the Mantaro <https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/392841541>) and

birds that Mark Robbins and Peter Hosner recorded in Ayacucho in 2012 <https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/173820, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/173847> and in

the southern Vilcabamba in Cusco in 2012 <https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/174006,https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/186972> sound

considerably more like nominate marcapatae. We don't have recordings from the

type locality of C. m. weskei, so we can only assume that these more

southerly recordings are representative of the topotypical voice of the taxon.

So what does this apparent vocal shift mean across the Mantaro mean? Well, we

have no specimen material to review, but I suspect there may be an undescribed

taxon involved with the birds north of the valley, so Boesman's assessment of

voice doesn't actually apply to true C. m. weskei, but probably to

another taxon altogether which looks very like it. In the end, I think that

situation needs to be sorted out before we can make species-level changes in

the taxonomy of the C. marcapatae group. So, NO to splitting for now.”

Comments

from Glenn Seeholzer (voting for Remsen): “YES.

“At

the time of its description Cranioleuca

marcapatae weskei was only known

from the isolated northern Cordillera Vilcabamba. C. m. weskei and C. m. marcapatae

(hereafter weskei and marcapatae) display the same plumage

polarity (white vs. chestnut crown) that was used to diagnose the subspecies of

C. albiceps. The initial placement of

weskei as a subspecies of marcapatae was therefore based on the

comparative BSC approach - white vs. buffy crown coloration was not a

pre-mating barrier in C. albiceps

(widespread occurrence of intermediate crowns) therefore weskei and marcapatae

would also not exhibit reproductive isolation should they come into contact.

Specifically, the presence of extensive intermediate crown coloration between

the geographic and phenotypic extremes of C.

a. discolor and C. a. albiceps was considered a sign of gene flow. By this

same logic, if populations of weskei

and marcapatae come into contact and

show no evidence of intermediate crown coloration (i.e. introgression) this

would indicate that gene flow between the taxa is minimal and that weskei is a species.

“Variation in crown color in C. marcapatae

“Weskei was described based on

crown color – white – relative to the chestnut-crowned nominate subspecies

(Remsen 1984). Based on the specimens available at the time Remsen considered

crown color to be a discrete trait in C.

marcapatae in contrast to the continuous variation in crown color between

the buffy discolor extreme and the

white nominate subspecies of Cranioleuca

albiceps. Examination of recent specimens and ML photos (N=191) reaffirms

Van’s original assessment that there is no evidence of intermediate crown

coloration in either subspecies of C.

marcapatae, even where there come into closest contact in the southern

Cordillera Vilcabamba.

“See

the following ML image galleries

●

weskei (north

of the Río Montaro)

●

weskei (south

of the Río Montaro, west of the Río Apurímac)

●

weskei near

contact zone (east of the Río Apurímac)

●

marcapatae near

contact zone (west of -72°W)

●

marcapatae away

from contact zone (east of -72°W)

●

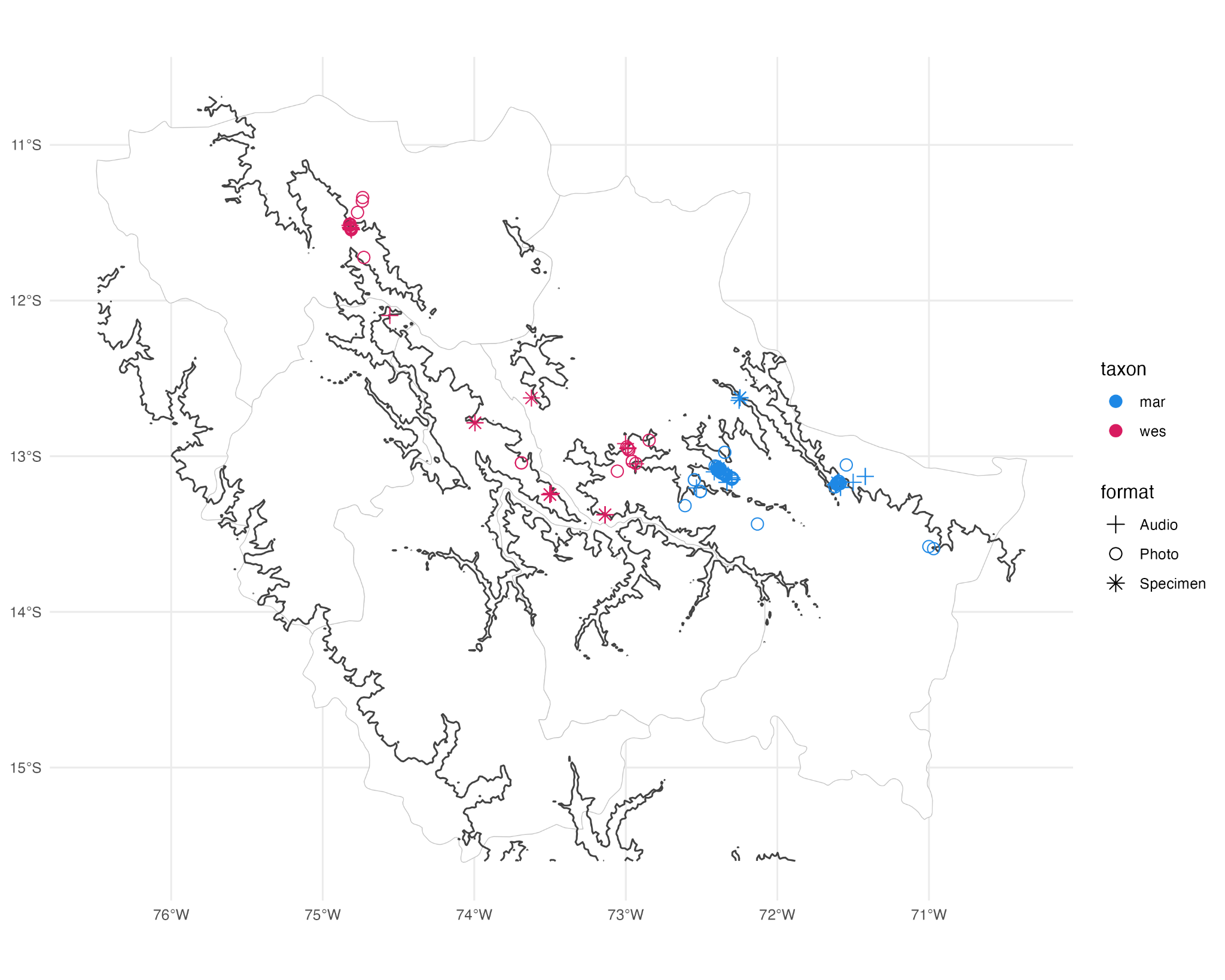

“The

ML photos fill in a large gap in specimen sampling in the southern Cordillera

Vilcambamba (Figure 1), and the two subspecies are now documented to occur

within ~40 linear kilometers of each other (60-70 km following the 3000 m

contour).

“Figure 1 - Map of vouchered records of Cranioleuca marcapatae. Color indicates

subspecies, shape indicates documentation method. Dark lines are 3000 m

elevational contours. Gray lines are departmental boundaries.

Below are the two closest photographs with

clear views of the crown.

“marcapatae

●

ML440773301 - Inca Trail above

Macchu Picchu (-13.226, -72.509)

●

ML217863001 - Camino Salcantay

above Colcapampa (-13.318, -72.609) - even closer than above but can’t confirm

that the crown is not intermediate

“weskei

●

ML492931841 - headwaters of the

Rio Vilcabamba near Lucma (-13.046, -72.934)

“These

localities occur at the headwaters of the Ríos Vilcabamba and Urubamba which

converge downstream of Machu Picchu. Examination of the satellite imagery of

the massif between these two rivers shows no obvious break in this species’

habitat (2500-3500 m montane forest). Unvouchered eBird observational records (S59715216, S33942238, S127451093) from near Mutuypampa

(-13.181,

-72.718)

occur midway along the 3000 m contour between the closest vouchered localities.

Given that weskei occurs across

significant habitat breaks elsewhere in its range (e.g. Río Apurimac, Río

Montaro), it’s a safe bet that some flavor of C. marcapatae continuously occupies the 2500-3500 m habitat band

between these rivers making this region a contact zone.

“For

comparison, specimens of Cranioleuca

albiceps from southern Puno to Cochabamba show the full spectrum of

intermediate crown coloration from white to buffy (see Van’s specimen series)

while spanning almost 500 linear km and numerous breaks in the 2500-3500 m

habitat band. Lest we doubt the ability of photographs to document intermediate

crown coloration, see this photo of two C. albiceps individuals next to each

other showing two different points on the white to buffy spectrum or this intermediate

individual.

“If

there were intermediates between weskei

and marcapatae outside of the

unsampled contact zone we would probably know it by now.

“Contact zone scenarios

“As

explained above, it is likely that weskei

and marcapatae come into contact

somewhere along the 2500-3500 m habitat band between the Ríos Vilcabamba and

Urubamba. There is a spectrum of possible patterns that we could expect in this

contact zone. At one extreme is assortative mating indicating reproductive isolation,

a slam dunk for treating weskei as a

species.

“At

the other extreme is a hybrid zone with panmixia creating a highly variable

population of individuals with intermediate crown coloration as seen in C. albiceps. If there is a hybrid zone,

it is a narrow one. From a strict BSC interpretation a hybrid zone with

panmixia demonstrates a lack of reproductive isolation and the interacting taxa

should be considered the same species. However, in practice we are highly

tolerant of this kind of hybridization between ‘good’ species.

“In

Cranioleuca, Seeholzer and Brumfield

(2017) documented a ~1000 km gradient in body size, plumage, and genetics in C. antisiensis which resulted in the

southern baroni and northern antisiensis groups being lumped. This

gradient was highly correlated with elevation and temperature and is best

considered a cline, not a hybrid zone. The only well-documented hybrid zone in Cranioleuca is between C. pyrrhophia and obsoleta. A thorough phenotypic study showed it to be 100s of

kilometers wide with extensive intermixing of pyrrhophia and obsoleta

phenotypic traits. Claramunt (2002) concluded that either the hybrid zone was

young or that some form of reproductive isolation exists maintaining the

phenotypes of the taxa in the face of gene flow. In either case, Claramunt

recommended the taxa continue to be treated as separate species.

“More

broadly we treat the members of many other super-species complexes with

well-documented hybrid zones as separate species. Manacus candei, vitellinus,

aurantiacus, and manacus all hybridize where their ranges abu and despite diverse

treatments we currently consider these all separate species. Other examples

include Rhegmatorhina berlepschi/hoffmansi, Myioborus melanocephalus/ornatus, Ramphocelus carbo/melanogaster, Thraupis

episcopus/sayaca, and of course most of the taxa that hybridize across the

Great Plains suture zone.

“I’m

too checked out of the speciation and taxonomy literature to parse the

meandering rationales for maintaining hybridizing taxa as species but if we’re

going to be consistent, then a narrow hybrid zone between weskei and marcapatae

would not be incompatible with treating them as species.

“Vocalizations

“After

listening to recordings, I agree with Dan that southern weskei and nominate marcapatae

sound very similar. Here are links to four galleries of ML recordings of the

short song (the most commonly recorded vocalization) so others can assess for

themselves.

●

weskei

(north of the Río Montaro)

●

weskei

(south of the Río Montaro, west of the Río Apurímac)

●

weskei

near contact zone (east of the Río Apurímac)

●

marcapatae near

contact zone (west of -72°W)

●

marcapatae away

from contact zone (east of -72°W)

“I

don’t have time to do a quantitative analysis, but I also don’t think it’s

necessary in this case. Absent an obvious diagnostic plumage feature like crown

color, the minimal vocal differentiation between southern weskei and nominate marcapatae

would indeed point us to one species. BUT we do have an obvious diagnostic

plumage feature that shows no evidence of introgression despite close contact.

A diagnostic vocal difference would help the case for species status, but the

absence of vocal differences doesn’t detract from it.

“Dan’s

intriguing observation that weskei

north of the Montaro in Junín sound different is not relevant to the question

of reproductive isolation or diagnostic characters between weskei and marcapatae

where their ranges abut. I will add that in addition to that population having

a higher, faster short song, the image galleries for this population also seem

to show a more extensive buffy wash to their throats compared to individuals

east of the Río Apurímac. Certainly seems like it could be an undescribed taxon.

“Summary

“Weskei and marcapatae show a discrete difference in

crown coloration (white vs. chestnut) with closely abutting distributions and a

high likelihood of a contact zone. This contact zone does not occur at an

ecotone or biogeographic barrier. Song divergence is minimal but not relevant

to assessing gene flow when crown color can be used as a proxy. There is no

evidence of introgression in crown coloration suggesting that in the contact

zone there is 1) assortative mating or 2) a narrow hybrid zone without gene

flow into either taxon. Clearly additional specimens and photographs from the

presumed contact zone are desirable but this would not change the patterns

outlined above which are enough for me to consider weskei a distinct species from marcapatae.

“Thoughts

“It

was fun to think about Cranioleuca

again after so many years. Specimens are always the most desirable form of

documentation. but I was impressed with how useful ML photographs were for this

system. For assessing the distribution of a simple binary trait like crown

color, they certainly came in handy!

“A

modern genomics treatment C.

marcapatae/weskei and C. albiceps

would make a great dissertation project. Replicate systems with what appear to

be two different evolutionary outcomes. For the future intrepid graduate

student inspired by this system, here are some juicy looking sampling

localities in the contact zone.

●

Above

Huayrani (-13.070,

-72.829)

●

Achirayoc

(-13.062,

-72.765)

and trails above (-13.119,

-72.771)

●

Mutuypampa

(-13.181,

-72.718)

●

Colcapampa

(-13.319,

-72.669)

“Additionally,

C. marcapatae and C. albiceps presumably come into contact

somewhere between Marcapata, Cusco, and the Sandia Valley, Puno along with

potential contact zones for many other Bolivian Yungas endemics and their

northern counterparts. High priority region for some adventure ornithology.”

Comments from

Areta: “" I vote NO to the

split. After seeing the case of C. baroni-antisiensis, taking a look at the

intergradation in crown color in C.

albicapilla (albicapilla

grades into albigula,

according to the HBW), knowing about the drastic geographic variation in

plumage and the dramatic within-locality vocal variation in C. pyrrhophia, thinking on

the geographic variation in crown color as exemplified by C. albiceps by Remsen, and

being absolutely convinced that the Boesman analysis is woefully incomplete for

a Cranioleuca I

don´t think there is a strong case here.

“Note:

there are sheer amounts on variation of speed of delivery, frequency patterns,

note shape, duration and pretty much any aspect one may want to consider even

in successive "songs" of the same individuals of Cranioleuca; therefore, any

analysis will need to a) have large sample sizes and b) take extra care to

compare the same vocalization types under the same motivational context [even

then, it might be mare]). So, I think that the vocal analysis needs to be

seriously downplayed here, given the high chances that it mischaracterizes the

differences and similarities in the voices of weskei and marcapatae.

Based on a cursory investigation of sounds, I don´t find any striking

difference in the "double-calls" or in the "short-song" of

these taxa. Of course, this is just a quick-and-dirty analysis, but I am

underwhelmed by the differences (unsurprisingly, given how difficult to

separate on vocalizations are several species of Cranioleuca...).

“Also,

there is this report by Hosner et al. (2015 WJO 127:563–581

, p. 575):

‘White-crowned'

Marcapata Spinetail (Cranioleuca marcapatae weskei).—We found this

spinetail uncommon to fairly common at all forested sites at 2,800–3,600 m (KU

112900, 112843, 122581–2 and CORBIDI LCA 2012-24, MCCF 476, MBR 8315, MBR 8339;

MJA 322, ML 173820, 173847, 174006–7, 174037, 186915, 186972). In June at Ccano,

a few non-vocalizing individuals were encountered. However, in September and

October at Chupón and above Paccaypata, presumed pairs and family groups (up to

4 individuals) were seen and heard daily as they foraged in Chusquea

bamboo understory at 3,000–3,600 m. The Ccano and Chupón records are the first

for Ayacucho. Cranioleuca m. weskei has also been documented recently

in Junín (e.g., XC 74478, 155740). Specimens from Paccaypata differed from

typical C. m. weskei in that the face and lores were plain gray,

rather than buffy, and a few white crown feathers had faint rufous edging.

These characters suggest that birds in Paccaypata may be intergrades between C.

m. weskei and nominate C. m. marcapatae from further east in

Cuzco. Apparent intergrades with a mix of rufous and white crown feathers have

been observed around Vitcos (13.111º S, 72.938º W, 3,000 m; Jul 2014; B.

Walker, pers. comm.)’. (Thanks to Tom Schulenberg for pointing this out in our

WGAC discussion).

“Thus, I see no reason to split weskei at present.”

Comments from Stiles: “NO on current

information. Given the variation in crown color within the close relative albiceps,

and with its white crown the primary basis for recognizing weskei as a

separate species, at least more genetic data and information on exactly where

recordings of several (and which?) taxa

were made will be needed to sort this out.”

Comments from Robbins: “After reading all the comments, including a number since I

first reviewed this proposal has me still on the fence. Nonetheless, if we must make a decision based

on current information I think it is premature to treat weskei as a species,

thus I vote NO for now.”

Comments

from Claramunt:

“YES. A difficult case as there are many in the genus Cranioleuca. But I would ask those that

voted “NO” to reconsider. Glen explained several key aspects very well. My

impression is that in the context of Cranioleuca taxonomy, weskei is clearly a different species. I totally

understand why Van described it as a subspecies: an isolated peripheral

population with a single (albeit conspicuous) plumage difference that happened

to be a variable trait in the sister species. Now we know that the distribution

of weskei is much larger, even larger than

that of marcapatae (still a minor point). But consider

the following:

1) It is not

uncommon for good species in Cranioleuca to differ in a single trait affecting the color

of the head: C. obsoleta

– C. pallida, C. erythrops – C. curtata. C. marcapatae and C. weskei would be just another case of that.

2) Crown color has great potential for

affecting mate choice and determining reproductive isolation in Cranioleuca and spinetails in general. As pointed out

before, different species of Cranioleuca typically differ more in plumage than in songs.

3) While albiceps shows a gradation in the color of the crown,

the crown varies from white to light cinnamon only, not to rufous like the

crown of marcapatae. The

magnitude of the difference is much greater in the case of marcapatae and weskei.

4) Also in contrast to the albiceps case, the difference between marcapatae and weskei is discrete; intermediate phenotypes have not

been described so far, with the exception of the mention of specimens of weskei from one locality in which “… a few white crown

feathers had faint rufous edging,” and a report of another population with

birds with crowns with mixed crowns (Hosner et al. 2015). I would take those

observations with a grain of salt until more details are published.

5) As pointed out by Glenn, if there

is indeed some hybridization, it seems very limited geographically.

“Future work on these species will tell what is exactly going on,

but in the context of our current taxonomy of Cranioleuca, I think that weskei should be treated as a species.”

Additional

comments from Stiles:

“I find Santiago's comments very interesting,

especially his overview of the main part of the distribution of Cranioleuca

- hence, I am willing to change my vote to YES for proposal 1010.

Comments

from Ryan Terrill (voting for Del Rio): “YES -- I think this is a very borderline case

that warrants more data and could go either way, but Glenn's comments help a

lot here and are appreciated. It does seem like there is likely to be a contact

zone somewhere in the headwaters of the Vilcabamba/Urubamba rivers, which would

be great to visit and sample. But, as noted, if they do come into contact, they

either don't interbreed, or if they do, form a very narrow hybrid zone. Other

examples of variation within Cranioleuca species show a lot of variation

and trait introgression – notably the C. antisiensis and C. albiceps

complexes. In reference to

Santiago's comments about crown color as a trait affecting mate choice, I have

seen pairs of C. albiceps segregate by crown color within their contact

zone in Cochabamba, see my notes in this checklist -- https://ebird.org/checklist/S42501143 "A

pair of birds near the top of the road had pale yellow crowns, noticeably and

distinctively paler than the orange crowned birds just down the road". Of course, this is

only one anecdote.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“YES, with hesitation, but Santiago’s and Glenn’s arguments are compelling. It

is unfortunate that more genetic data from additional individuals and formally

analyzed songs are not yet available.

“Regarding

the crown variation in albiceps, I don’t consider it a problem. It’s

plausible that this variation existed in ancestral weskei but was lost

with the fixation of the white crown. This is consistent with an isolated

population in a small range, where drift and sexual selection could drive rapid

evolution. I also agree with Santiago that a white crown could play a crucial

role in pre-zygotic isolation. Combined with the long genetic branch between weskei

and marcapatae, these points support a split.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“YES. As

others have noted, this one is something of a borderline case in terms of

supporting evidence, one way or the other.

I listened to all of the linked vocal samples that Glenn provided, and I

remain unimpressed with any alleged vocal differences between weskei and

marcapatae. That having been

said, I could say the same about the songs of many species-pairs within Cranioleuca -- so many of them are extremely similar in

songs, and I’ve noted marked variation from one individual to the next from

within the same population, and even from one song to the next from the same

individual, particularly depending on state of arousal (e.g. in response to

playback). Throw in the fact that many

species in the genus duet, and, that you’ve got no sexual dimorphism to

distinguish the sex of a lone vocalizing bird, and it means that even a

detailed quantitative vocal analysis will have a hard time controlling for sex

and number of individuals when analyzing archived recordings from third parties. So, I would agree with Glenn that the absence

of a quantitative vocal analysis in this case is not a deal-breaker, given that

we do have an obvious, discrete and diagnostic plumage feature, for which we

have no evidence of introgression despite close contact. To this end, I am persuaded both by Glenn’s

reasoning, and, particularly, by the points made by Santiago regarding the

potential for crown color or other single plumage characters affecting mate

choice in Cranioleuca species-pairs (and the examples Santiago offered

are spot-on in my opinion – my mind went immediately to pallida versus obsolete,

whose songs I can never personally discriminate in the field), and in the

discrete nature of the rufous versus white crown color in marcapatae

versus weskei, as opposed to the continuous variation in albiceps. Also, as pointed out by Glenn, Ryan and

Santiago, assuming there is a contact zone between weskei and marcapatae,

the two are either not interbreeding at all, or, the hybrid zone, if it exists,

must be extremely narrow, given the complete lack of evidence for phenotypic

introgression in crown color.”

Additional

comments from Jaramillo: “I just did a quick read through of the proposal, and the

information I had not seen before. I am switching to a YES on Cranioleuca

weskei based on Glenn's information and Santiago's analysis of Cranioleuca

in general. It may shift in the future as we obtain more information, but I am

comfortable with a YES vote based on what I read and understand right now.”