Proposal (1012) to South

American Classification Committee

Treat Sphenopsis

ochracea and Sphenopsis piurae as separate species from S.

melanotis

Note: This is a

high-priority issue for WGAC.

Background: Our SACC note on this is as follows:

10. Despite strong differences in some plumage

characters, Sphenopsis (formerly Hemispingus) melanotis

has been treated a polytypic species based on shared plumage themes (Hellmayr

1936, Zimmer 1947, Storer 1970a, Meyer de Schauensee 1970, Dickinson &

Christidis 2014. and others).

García-Moreno et al. (2001) and García-Moreno & Fjeldså (2003) found

that the distinctive taxon piurae, currently treated as a subspecies of Sphenopsis

melanotis (e.g., Meyer de Schauensee 1970), is more distant from the latter

than is S. frontalis, and that piurae is basal to frontalis +

melanotis; these analyses, however, were based on only ca. 300 base-pairs

of mtDNA. Ridgely & Greenfield

(2001) treated piurae as a separate species from H. melanotis

based on plumage and vocal differences. SACC proposal to

recognize piurae as a species did not pass. Hilty (2011) also treated piurae as a

separate species. Ridgely &

Greenfield (2001) and Hilty (2011) further recognized the subspecies ochracea

as a separate species based on plumage differences. Halley (2022) treated piurae and ochracea

as species based on distinctiveness of plumage.

SACC proposal needed.

We

currently treat Sphenopsis (ex-Hemispingus) melanotis

(Black-eared Hemispingus) as a highly polytypic species, as did Dickinson &

Christidis (2014), who recognized 6 subspecies in 3 groups in the humid Andes:

(1) nominate melanotis

(Andes of NW Venezuela to e. Ecuador), berlepschi (e. Peru), and castaneicollis

(Eastern Andes of S. Peru and Bolivia)

(2) ochracea (

Western Andes of sw. Colombia and nw. Ecuador)

(3) piurae (s.

Ecuador, NW Peru) and macrophrys (Western Andes of c. Peru).

We

rejected a proposal in 2007 (SACC 284) based largely on weak

genetic data and absence of data on vocalizations.

Here

is a crude home-made representation of the distribution of the taxa in

question. All photos are from Macaulay

Library (melanotis by Ben Jesup, ochracea by Angel Argüello

Méndez, piurae and macrophrys by Fernando Angulo, berlepschi

by José Martín, castaneicollis by Tini & Jacob Wijpkema). Note the subspecies macrophrys Koepcke 1961 has been generally

overlooked (“Near piurae but with broader white

superciliaries, a broader and more conspicuous gray band on nape and

post-auriculars, and underside of wing more whitish”). See also Halley (2022) for specimen photos.

From

the differences in plumage, one can quickly spot the problems. It is not immediately obvious why ochracea

was ever considered conspecific, although the rationale was likely that it

looks like a typical smudgy, obscure Chocó representative of a group of more

brightly colored taxa. It also could be

argued that nominate melanotis stands apart from all the rest. From the perspective of those most familiar with

birds north of the Marañon, such as Ridgely and Hilty (see SACC Note), one

might immediately reject piurae as being conspecific with nearby

nominate melanotis because of the plumage differences, but for those

more familiar with taxa south of the Marañon, such as J. Zimmer and Schulenberg

et al. (“Birds of Peru”), piurae looks similar to distant S. m.

castaneicollis. I suspect that a

formal analysis of plumage similarities could go any number of ways depending

on how one scores the plumage characters, e.g. see Halley (2022: 221). Lots of “eye of beholder” reasoning would be

involved. It seems we have a classic

conundrum concerning taxon rank of distinctive allotaxa, with the only clear

case being macrophrys as a subspecies regardless of species limits.

New

information:

Del Hoyo & Collar (2014) treated ochracea

and piurae as a separate species based on the Tobias et al. point

scheme as follows (provided by Pam Rasmussen):

“Western:

https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/historic/hbw/bkehem3/1.0/introduction

[ochracea] Usually treated as conspecific with S. melanotis

and S. piurae, but each differs markedly in plumage and habitat and

hence is tentatively accorded species rank here (although songs of present

species and melanotis difficult to distinguish (1) ); review of group

warranted. Monotypic.

“Piura:

https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/historic/hbw/bkehem1/1.0/introduction

Usually

treated as conspecific with S. melanotis and S. ochracea (see

latter); present species exhibits some vocal differences, and limited molecular

data suggest that it is at least as distinct from S. melanotis as latter

is from S. frontalis; review of group warranted. Two subspecies

recognized.”

The

habitat difference alluded to likely comes from Ridgely & Greenfield’s

statement: “unlike.

[melanotis and piurae], the Western Hemispingus does not show

any particular predilection for an understory of Chusquea bamboo.” However, photos of ochracea in

Macaulay show bamboo in 11 of the small number of photos of the species, so

perhaps that needs re-evaluation.

Certainly it should not play a role in determining species limits.

Boesman (2016k) analyzed an

unspecified number of recordings from unspecified locations. Apparently, vocalizations of berlepschi

and hanieli were not analyzed. Here

are his main conclusions:

“From the above, it is clear that duet song

of all three species is structurally similar. There seems to be however a

closer resemblance between duets of H. ochraceus and H. melanotis.”

“All in all, we can conclude that voice of H. ochraceus is about identical to H. melanotis.”

“Voice of piurae

at the other hand is quite distinctive

and can be safely told apart.”

“Race castaneicollis of H. melanotis

also differs from other races of this species”

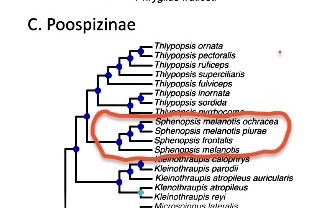

Price-Waldman

(2019), an unpublished dissertation from Kevin Burns’ lab, used UCE data to

construct a phylogeny of the tanagers.

As cited by Halley (2022), the topology for this group was (((ochracea,

piurae), frontalis), melanotis), which would thus require

separation, minimally, of ochracea + piurae as a separate species

from melanotis.

Expanding

frontalis to include all of the melanotis group is clearly

untenable because frontalis is broadly sympatric with melanotis

representatives. Tangentially, note that

the subspecies of frontalis of the Coastal Range of Venezuela, S. m.

hanieli, superficially looks as much like a melanotis type as a

representative of frontalis, and Halley (2022) emphasized the

distinctiveness of this taxon and its tentative placement within S.

frontalis. Here’s a photo from

Macaulay by Margaret Wieser from Aragua:

So,

species limits need to be changed, but what do we do with berlepschi, castaneicollis,

and even hanieli? Certainly by

extrapolation, the differences in plumage between nominate melanotis and

berlepschi + castaneicollis are of the same general magnitude as

those between nominate melanotis and ochracea, again depending on

how one weights characters and determines homoplasy.

Halley

(2022) made two important contributions.

First, he pointed out that the Garcia-Moreno et al. data-set actually

lacked a sample of ochracea despite its claims otherwise, and second, he

assembled the few existing specimens of ochracea to show that it had

been inaccurately illustrated in all published works, with respect to

coloration of the underparts, which are indeed ochraceous, and in some cases

with respect to having a mask, which is minimal. Halley did some solid, baseline

alpha-taxonomy that will be useful for all future analyses.

Discussion

and Recommendation:

Just to understand the history of all this, I have recorded here my wanderings

down several rabbit holes (to use a worn-out metaphor). I was tempted just to delete everything and

just present the Price-Waldman tree, which requires at least a 2-way

split. But that makes me

uncomfortable. The thesis is

unpublished. Given the surprising

finding, were vouchers double-checked?

And what about unsampled berlepschi-castaneicollis, for

which Boesman has evidence for vocal distinctiveness (at least for castaneicollis)

and which, as a group, are phenotypically distinctive? Do we keep them with melanotis despite

plumage and vocal differences? And what about the largely neglected hanieli

issue? My gut instinct is not to meddle

with our current classification, despite the possibility of a paraphyletic melanotis,

until all these other issues are sorted out.

In contrast to the philosophy of many colleagues, I actually like

conflict among world classifications because it signals honestly and appropriately

that there is considerable uncertainty, which would otherwise be masked. Nevertheless, I don’t have a strong

recommendation and will wait to see what others say.

English

names: “Western Hemispingus” and “Piura Hemispingus”

have more than two decades of traction in the literature. I suspect “Western” is not a name anyone

really likes. Hellmayr (1936) called it

“Ochraceous-bellied Hemispingus”. The

reason why Ridgely & Greenfield (2001) didn’t go with this is because they

described the underparts as “drab buffy olivaceous”, although Greenfield’s

illustration of the head shows the throat at least to be ochraceus. The ochraceous belly (vs. all of the

underparts) highlights what seems to be a unique feature (and it also helps

remember the scientific name ochracea).

I predict if Bob Ridgely knew what we do now about ochracea, he

would gave stuck with Ochraceous-bellied.

I am willing to write a short proposal on this if anyone else is favors

overturning 20+ years of stability. If

it were 50+ years of stability or if all classifications treated it as a

sperate species “Western Hemispingus”, then I would object to changing the

name, but if we are ever going to do it, now is the time (if the proposal

passes). “Ochraceous-bellied

Hemispingus” would have the additional advantage of pointing out the problems

with illustrations of ochracea, as noted by Halley (2022). In contrast, “Piura Hemispingus” was used by

Hellmayr (1936) and thus has been in the literature for at least ca. 88 years.

This dodges the problem that none of

these species are in the genus Hemispingus any longer, but that’s a

separate problem that would have to consider the broader diaspora of former Hemispingus. For now, I’m personally content with

“Hemispingus” as a vague morphotype. i.e. roughly as a “half finch”, as in the

derivation of the genus name, in the interests of stability, but if anyone

wants to tackle this problem, feel free.

References: (see SACC

Bibliography

for standard references)

HALLEY, M. R.

2022. Taxonomic status of the

Western Hemispingus Sphenopsis ochracea (Thraupidae) and a review of

species limits in the genus Sphenopsis P. L. Sclater, 1861. Bulletin British Ornithologists’ Club 142:

209-223.

ZIMMER, J. T. 1947. Studies of

Peruvian birds, No. 52. The genera Sericossypha, Chlorospingus,

Cnemoscopus, Hemispingus, Conothraupis, Chlorornis, Lamprospiza, Cissopis,

and Schistochlamys. American

Museum Novitates 1367: 1-26.

Price-Waldman, R. M. 2019. Phylogenomics, trait evolution, and

diversification of the tanagers (Aves:Thraupidae). M.Sc. thesis. San Diego State Univ.

Van Remsen, June 2024

Vote tracking chart:

https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart968-1043.htm

Comments

from Robbins:

“NO. Another messy situation for all the reasons that are pointed out in the

proposal. Given the number of issues that need to be addressed, as summarized

by Van, for now I vote NO.”

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“YES – You only need to look at the map, compare to other similar Andean chain

“superspecies,” look at the photos and you have the informed suspicion that

more than one species is involved in melanotis. The unpublished (thus far) DNA work, the

vocal information that is available adds more pieces to the puzzle, and they

also lean in the way of separating this chain of taxa into multiple species. I

am comfortable in voting yes, and comfortable in understanding that in the

future there may be future changes to this complex.”

Comments from Areta: “A conflicted NO. I think that

there are at least 3 species in S.

melanotis (and probably more), but I feel quite uncomfortable with the lack

of data on berlepschi

and melanotis

(taxa sampled by Price-Waldman 2019: Sphenopsis

melanotis castaneicollis FMNH 430079 / Sphenopsis

melanotis ochracea ANSP 149722 / Sphenopsis

melanotis piurae FMNH 480966) and I don´t like to guess. berlepschi is clearly more

similar to melanotis,

so it might not be much of a problem (perhaps...), and I could accept that it

is conspecific with melanotis.

But castaneicollis,

with its broad black mask and chin, contrasting white supercilium and

rufous-chestnut large pectoral band is much more like the widely allopatric piurae, while also being

quite distinct from melanotis/berlepschi. Ochracea is ridiculously

different from the rest, yet based on Price-Waldman it is sister (how deeply

diverged? we don´t know) to the distinctive piurae,

both from the W slope of the Andes. Therefore, the drabbest and the most

colourful forms are sister, suggesting that concluding on the phylogenetic

placement of other taxa based on plumage is risky. Should we go with geography

then? Risky again. Then there are also Van´s worries about macrophrys and S. frontalis.

“This is one of the situations in which there is

(barely) enough information to split some of the taxa, but in which information

on key taxa is missing to properly establish species limits and in which we

must guess in order to decide. Shall we stick to the old taxonomy or move to a

newer one that may have other problems? Also, the Price-Waldman phylogeny has

not been adequately published, and all we seem to have at hand is the topology

of a tree. Halley (2022) provides an excellent overview of the taxa involved

and clarifies some problems while proposing an alternative taxonomy. Although

it seems clear that the single-species treatment will fall, I am not convinced

about how many species we should recognize and how each of them should be

confirmed. Therefore, I vote NO to any split for the time being.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“NO. The whole situation is simply at the stage where too little is known about

the genetics and vocalizations of too many taxa, and their geographic

distributions appear to present a more complicated picture. A more

comprehensive study of Sphenopsis is badly needed - splitting these two

now might be jumping the gun.”

Comments

from Lane:

“NO. Another situation where I think we are voting without all the necessary

information in hand to make an informed decision. What harm is there in waiting

for someone to compile those data?”

Comments

from Niels Krabbe (voting for Del-Rio): “NO. There is no indication that

Price-Waldman (2019) double-checked the identity of his frontalis (MSB

31856 (Peru: dpto. Amazonas; prov. Utcubamba; dist. Lonya Grande; ca. 4.5 km N

Tullanya). Halley (2022) certainly did not. However, as both Price-Waldman and

García-Moreno & Fjeldså (2012), the latter using a double-checked frontalis

from Imbabura, W Ecuador, found frontalis to be embedded in the melanotis

complex, there is no reason to doubt the correct identification of the Amazonas

specimen.

“A

recent, as yet unpublished find by Jonas Nilsson (pers. comm.) of a population

in the Chilla Mts of southern Ecuador (a ridge connecting the east slope with

the west slope) that appears intermediate in plumage between the vocally

similar ochracea and melanotis further underscores the need for a

detailed study that includes all the Sphenopsis forms before changing

the current classification.”

Comments from Claramunt: “YES. The only problem here is

our regressive tradition in ornithology of stuffing taxa into polytypic species

based on pure speculations about degree of differentiation. The actual

information we have is: 1) subspecies now included in melanotis are not each other’s close relatives because of

the position of S.

frontalis (Garcia-Moreno

et al, Price-Waldman). 2) Examination of study skins point to the existence of

three well delineated taxa (100% diagnosable, Halley 2022): melanotis, ochracea, and piurae. The solution is simple: split the

polytypic entity into its fundamental units. And the result is totally coherent

from a biogeographical point of view. I fail to see problems with the proposed

taxonomy. In contrast, I don’t see any evidence supporting the traditional

treatment. Where is the evidence that ochracea or piurae are reproductively compatible with melanotis?”

Comments

from Remsen:

“NO. I appreciate Santiago’s points above except I’m not sure what the

appropriate species-level components are.

As for evidence for reproductive compatibility among various taxa, we

could say that about every single case of allotaxa ranked as species for which

vocalizations have not been properly analyzed.

I can see how the Peters-era people could consider them conspecific

because they all share plumage features to varying degrees and are clearly

allopatric replacements. What they were

basing their decision on implicitly is that one can line up specimens of the

taxa from the dull extreme of ochracea to the bright extreme of piurae,

and see a series of taxa that bridge the extremes. The problem is that they don’t line up in a

strict geographic sequence.

My NO is based on the quality and

quantity of data available. We’ve got an

unpublished dissertation for which a voucher needs to be checked. We’ve got a

vocal analysis that did not report N or localities, with a critical missing

taxon. We’ve got the conceptually flawed

Tobias et al. scheme that may have used faulty information on habitat. The genetic analyses have missing taxa. The argument for multiple species is built on

a flimsy assembly of substandard data to the point that I think there is more

to be gained by retaining the traditional classification until more solid data

are produced than by endorsing one or more splits on the basis of weak data. On the other hand, I suspect that there are

multiple species-level taxa in this complex awaiting to be properly elucidated

once more rigorous data are produced.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“NO, but hesitantly. As Santiago points out, the three units (melanotis,

ochracea, and piurae) are indeed diagnosable. However, we lack

sufficient knowledge about what might be occurring in a potential ochracea-piurae

contact zone in southern Ecuador (see Niels’ comments on Jonas Nilsson’s

unpublished data). This is a highly complex and understudied region that could

reveal fascinating patterns. We might be facing another conundrum like the Myioborus

ornatus-melanocephalus situation.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“NO. I agree

with the thrust of Santiago’s comments overall, and feel pretty certain that

there are, indeed, multiple species-level taxa currently nested within this

single polytypic “species”. But, as Van

points out, there are critical flaws in all of the various analyses supporting

the proposed splits, and Niels’ comments regarding as yet unpublished

observations by Jonas Nilsson of a population in southern Ecuador that is

intermediate in plumage between ochracea and melanotis further

suggests that we should tap the breaks on making any premature moves until we

have more expansive data sets for all of the populations.”