Proposal (1015) to South

American Classification Committee

Treat Rauenia darwinii

as a separate species from Rauenia bonariensis

Note: This is a

high-priority issue for WGAC.

Background: Our SACC note on this is as follows:

19bb. The Andean subspecies darwinii was formerly (e.g., Chapman

1926, Zimmer 1930) considered a separate species from Pipraeidea (ex-Thraupis)

bonariensis, but Hellmayr (1936) treated them as conspecific as in all

subsequent classifications, including Zimmer (1944). Del Hoyo & Collar (2016) treated the

northern subspecies darwinii as a separate species (“Green-mantled Tanager”)

based in part on differences in song described by Boesman (2016k).

Dickinson

& Christidis (2014) treated these as single polytypic species, with 4

subspecies placed in two groups:

(1) darwinii

from Andes of Ecuador through Peru to n. Chile and n. Bolivia (La Paz) + composita

from c. Bolivia in Cochabamba and Santa Cruz

(2) schulzei

from se. Bolivia, w. Paraguay, and nw. Argentina + nominate bonariensis

of ne. Argentina, Uruguay, and se. Brazil

Their

construction of the group composition is a mistake. Darwinii stands alone in having an

olive-green back and being completely yellow below, whereas the other three

have black backs and orange underparts.

Zimmer

(1944) reversed his earlier species limits in treating them all as

conspecific. He did not give explicit

reasons, but in describing composita and discussing schulzei he

noted individual variation in the direction of darwinii:

“Several

specimens of bonariensis males have the black mantle feathers margined,

in varying degree, with olive. Many specimens of bonariensis, schulzei,

and composita have a band of olive separating the black of the mantle

from the orange of the rump, but many lack it. Some females (if the specimens

are correctly sexed) have as much blue on the head as certain females of darwinii,

although other examples of the Peruvian form reach an extreme not covered by

the other three subspecies. All these characters, however, are indicative of

the close relationship of all forms.”

Isler

& Isler (1987) did not address species limits but said: “In Bolivia, black-backed males sometimes have back

feathers edged olive or have an olive band between back and rump (Eisenstraut 1935)”

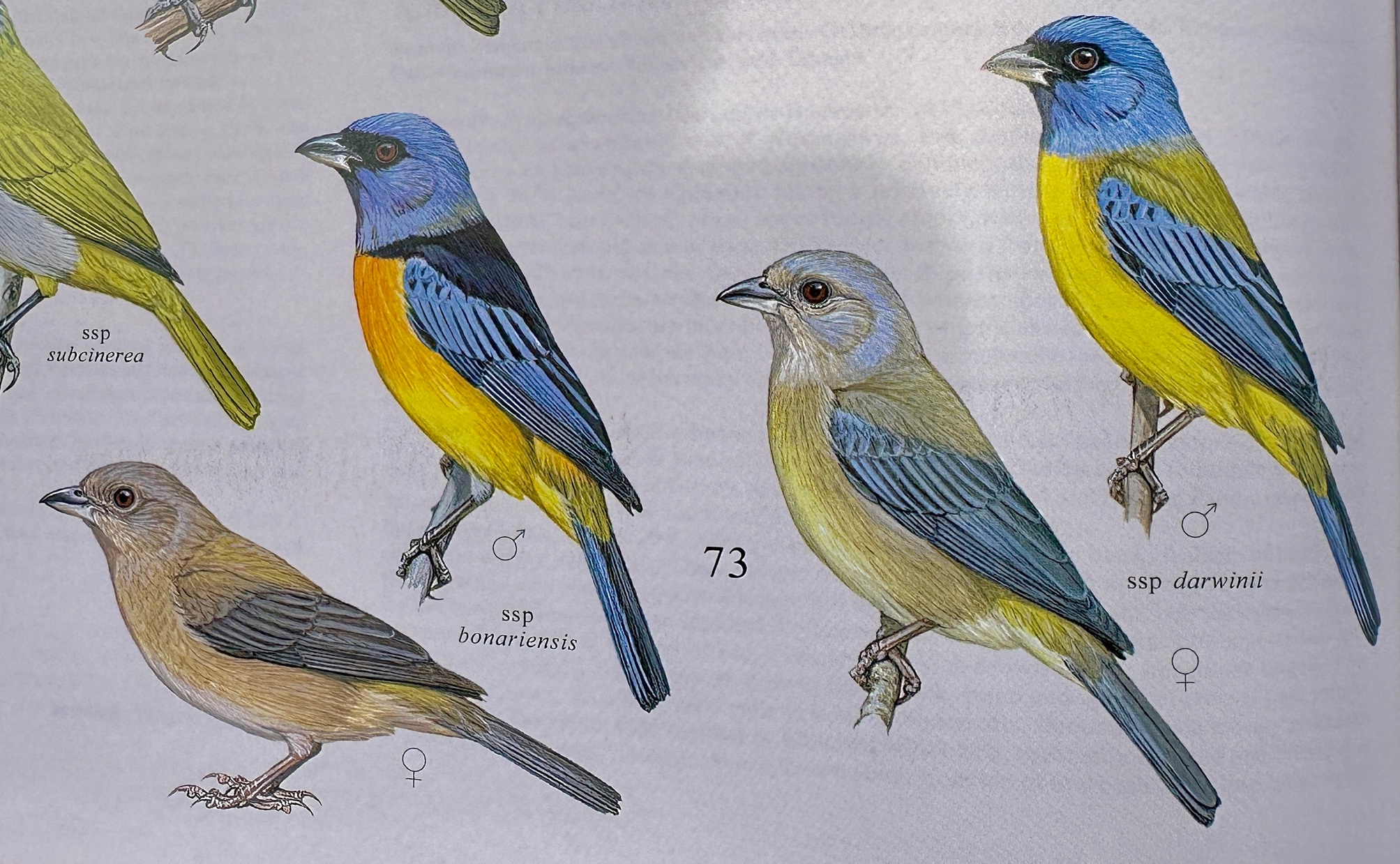

Here

is the plate by Hilary Burns in Hilty (2011):

Here

are photos of LSUMNS specimens; unfortunately, we don’t have any schulzei,

for which I have left a gap in each of the photos as a reminder that we’re not

seeing that taxon. (We actually have

surprisingly few specimens, period – I think this because we usually see them

in people’s gardens and chacras.) When

Zimmer described composita (which my auto-correct continues to insist

must be “composted”), he distinguished it from schulzei as follows: “Compared to T. b. schulzei of [Paraguay and] northwestern

Argentina, composita is larger, the blue of the head averages darker,

and the orange colors of the lower under parts and rump are a little less

intense.”

Here

is a photo of darwinii from Paul Molina A from Azuay from Macaulay Library:

Here

is a photo of composita from Cochabamba by Phillip Edwards from Macaulay

Library. By the way there is a photo

from Cuzco, Peru, of a bird indistinguishable from this one as far as I can

tell; it had been identified as darwinii , and I flagged it for review,

so Dan or Tom should have this in their review queue already. I mention this because it indicates that

these birds have good dispersal abilities, which is easy to predict from their

adaptability and association with human-altered habitat.

New

information:

Del

Hoyo & Collar (2014) treated darwinii and bonariensis as

separate species based on the Tobias et al. point scheme as follows (provided

by Pam Rasmussen):

"Usually

considered conspecific with P. bonariensis, but differs in its (in male)

olive-green vs black mantle, back, scapulars and chest side (3); yellow vs

flame-orange breast and rump (3); (in female) bluer crown, wings and tail (2);

more olive-yellow underparts and rump (ns[2]); and song with lower-pitched

notes in narrow frequency range (2) (1). Monotypic."

The

information on song comes from Boesman (2016k), whose examination of

recordings yielded the following conclusions:

“Song is quite variable, typically a sub-phrase of 2-3 notes repeated

several times, sometimes with slight changes. Often alternating downslurred and

(lower-pitched) upslurred notes. Pace also quite variable. Some song (?)

phrases lack the typical regular pattern. Overall, song is quite similar over

entire range, but: darwinii

can be recognized from all other races by the presence of lower-pitched notes,

which reach a max. frequency of c

3.5-6kHz (vs c 6-8kHz in

southern races, even more in bonariensis)

and cover a much smaller frequency range (c 2-3kHz vs 3-6kHz) (score

1+1=2).

“bonariensis apparently lacks a clear pattern of alternating downslurred

and upslurred notes, notes are higher-pitched and less melodious.

“We

can thus conclude that race darwinii

can be identified by alternating high-pitched and low-pitched notes, races composita/schulzei has

alternating upslurred and downslurred notes, while race bonariensis has

high-pitched repeated notes but lacks upslurred notes.”

Boesman (2016k) presented sonograms of

11 individuals, which I encourage you to look at to see the variability in song

noted by Boesman. Better yet, go right

to xeno-canto and do some sampling

or Macaulay (where you will find recordings by Ted Parker, Mark Robbins, and

regular contributors Niels Krabbe and Gary Rosenberg). Boesman had a lot of patience to deal with

all these predominantly weak recordings, often with lots of background

noise. This is clearly a difficult

species to record the song well (as are a lot of thraupids). Nonetheless, I’m pretty sure I can hear the

differences he described between the three groups.

Discussion

and Recommendation:

This is another tough case. It lacks a definitive, quantitative study, so at

this point we have to base a decision on fragmentary evidence. I can understand voting no on this one until

the missing pieces are in place, especially study of the contact zone, which

may never be thoroughly characterized if we endorse a split. However, I think I will vote YES on this for

two reasons.

First, darwinii and composita are

basically parapatric without little sign of hybridization. A number of taxa are separated by the dry

canyon of the La Paz river system that isolates taxa of humid forest on either

side. On the surface, this could be one

of those, but this is not a bird restricted to humid cloud forest but instead

is an edge species that does very well in towns and farmland and in fairly dry

areas. Note that darwinii is

found on both sides of the North Peruvian Low/Marañon, the biggest barrier to

dispersal for humid forest birds in the Andes, with no signs of phenotypic differentiation

on either side. Ditto the Urubamba and

other dry valleys. Composita

occurs in coastal Peru and n. Chile. As

noted by Isler & Isler (1987), southern populations are migratory. These birds clearly have strong dispersal

abilities. At a small scale, the area

where they likely come in contact in Bolivia is difficult to access and is

poorly studied bird-wise. So, you never

know but … all evidence so far suggest there is some sort of hard barrier to gene

flow that is not strictly geographic, given these birds’ habitat

tolerance. Zimmer’s interpretation of

the occasional olive feathers in the backs of bonariensis is not

necessarily due to any ongoing gene flow, but could reflect past connectivity

or shared ancestry. The Eisenstraut observation of olive dorsal feathers in

black-backed Bolivia birds (Isler & Isler 1987) is more suggestive of gene

flow and bears further investigation.

Second, we have some evidence of differences in

song, and I can hear the subtle differences discovered by Boesman. Would we rather have a larger, formal, peer-reviewed

study with dense geographic sampling? Of

course. But I think we have enough

information to suggest that the initial findings would hold up, although it

looks to me that composita-schulzei might be as different from bonariensis

s.s. as darwinii is in terms of song.

Strictly on the vocal information, one might argue for a 3-way split.

Finally, a minor, subjective point on color

differences. I am not particularly

impressed with the ventral color differences, which also appear to vary in

intensity within the bonariensis group, although that could be due to

age. The Macaulay photo galleries show

lots of individual variation, although some of that might be digital

artifacts. However, I am impressed with

the difference in back color. It’s an

abrupt shift from green to black. No

sign of a cline. All in all, I think the

available evidence shifts burden-of-proof on treating them all as conspecific,

but I could be talked out of that view.

I would really like to see an analysis of dorsal plumage variation in

males in central Bolivia – that’s not too much to ask for.

English

names:

BirdLife International retained Blue-and-yellow Tanager for the much more

widely distributed R. bonariensis (including composita and schulzei)

and used Green-mantled Tanager for R. darwinii. Although retaining the parental name for the

more widely distributed species is perhaps in accord with our SACC guidelines on

English names,

in this case, darwinii is found from Ecuador to n. Bolivia and is a

familiar bird on bird tours to those countries.

Also, part of the reason for the split was that the two differ in belly

color, with darwinii actually being the species that is “the” Blue-and-YELLOW Tanager.” To avoid that confusion, if the proposal

passes, I will do a proposal to make bonariensis s.s. the “Blue-and-ORANGE

Tanager” to highlight its most conspicuous plumage feature and to avoid causing

confusion for observers and to call attention to the change in species limits.

References: (see SACC

Bibliography

for standard references)

BOESMAN, P. 2016k. Notes on the vocalizations of Blue-and-yellow Tanager (Thraupis

bonariensis). HBW Alive

Ornithological Note 402. In: Handbook of

the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Van Remsen, June 2024

Vote tracking chart:

https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart968-1043.htm

Comments

from Robbins:

“NO. Plumage morphology: I looked at our (Univ. of

Kansas) material and one question that I have that might explain some of the

variation (ventral color?) within each form is that this tanager may have

delayed maturation; specimens with completely ossified skulls and no bursa are

clearly not in definitive plumage. Perhaps this is in already in the literature

(?). Clearly the dorsal coloration does separate darwinii from the other

forms. With regard to ventral concolor, at least all of our male specimens in

definitive plumage from dept. Cochabamba have bright orange underparts, whereas

a limited sample of darwinii, which are clearly in definitive plumage,

have yellow underparts.

“Vocalizations: I listened to what I consider primary song

(non-call notes) on both Macaulay and Xeno-canto. It is clear that there

is considerable variation and there may be two different primary vocalizations

in both groups. If one listens and compares relatively decent audio

recordings on Macaulay from just Ecuador you realize there is a fair amount of

variation within darwinii. Ditto for black-backed forms, e.g., compare

recordings from Cochabamba and northern Argentina on Macaulay. So, in sum, at a minimum, there needs to be a

rigorous comparison of analogous primary vocalizations.

“Although I've on the fence on this one, I would like to see a

more rigorous vocal analysis and a genetic data set to help guide what the best

course of action is. Thus, for now, a tentative NO.”

Comments from Areta: “An unhappy NO. I

am of the view that these two are different species, but that no one has

tackled the situation properly and splitting just because of the different

plumage aspect seems insufficient. There is geographic variation in male and

female plumage within the bonariensis

group that needs to be analysed and a genetic perspective could provide really

strong evidence in favour of the split. I have sound-recorded Rauenia bonariensis

extensively, and there is a great deal of variation across geography, but I

think that the vocalizations are quite different from those of darwinii, even allowing for

variation within each. However, the lack of formal bioacoustic analyses and the

lack of thorough studies on plumage variation in Bolivia where the two groups

could interact (I see photographs of pure black-backed birds very close to green-backed

ones in the Coroico area; is this seasonal or is this true breeding

parapatry/overlap?), leads me to vote NO to the split for the time being.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“NO, for now: the difference in plumage certainly suggests that darwinii may

be a different species, but a more thorough vocal analysis as well as genetic

data could tip the balance either way.”

Comments

from Lane:

“NO. It sounds like this is a ripe study for someone in Bolivia to tackle, but

until we understand what happens at the contact zone, it is probably best to

leave this complex as is.”

Comments

from Claramunt:

“YES. I agree with the arguments in the proposal. If

these two forms were reproductively compatible, they would be hybridizing in N

Bolivia. Unless this is an unusually sedentary tanager. And given that they

differ in at least two traits (intensity of ventral yellow, and black versus

green back), hybrids would be readily distinguishable by having unmatching

combinations of these two traits at least, and maybe intermediate amounts of

black on back. Therefore, the evidence points to reproductive isolation and

independent evolution despite geographical proximity.”

Comments

from Niels Krabbe (voting for Jaramillo): “NO. I have also noted that they take two

years to attain full adult plumage (at least males of darwinii). The

lack of clear intermediates in La Paz may suggest that two species are

involved, but how many specimens were examined? Vocally, these oscines do

differ notably, but still show some similarity, possibly enough for them to

accept each other (compare with the much more striking geographical variation

in Geospizopsis unicolor song). A genetic and morphological study

would settle it, but needs to be done before as split is warranted.”

Comments

from Ryan Terrill (voting for Del-Rio): “YES. I struggled with this one and went

back and forth a bit. This one is very close, and sort of similar to the Cranioleuca

marcapatae proposal we just voted on in that there may be a small contact

zone; but if there is we don't seem to have any data from the contact zone.

Similarly, if these taxa are syntopic, they either breed together in a very

narrow hybrid zone, or don't breed together. However, a couple big differences

are that southern populations of the bonariensis group are migratory,

and both taxa probably move/disperse quite a bit -- I wonder if the composita

photo Van mentions from Cuzco is a wintering migrant. I don't know that a

wintering bird would necessarily breed with resident populations; but the high

dispersal and movement of these birds probably weighs against the idea that

there may be a very narrow hybrid zone somewhere in the upper Cotacajes region; and if they were interbreeding freely we

could probably expect to see intermediate individuals all over the place. I

asked some folks at the LSU museum to look at birds from around where a contact

zone might be -- which would probably be the Inquisivi/Cotacajes region near the La Paz/Cochabamba border, and was

told there weren't any obviously intermediate birds -- same went for a search

of photos on ebird. Of course, the "best"

intermediate individuals would be a male in definitive plumage -- it looks to

me like southern groups show green backs in formative plumage and black in

definitive basic, so we want to watch out for birds undergoing second prebasic

molt like this one: https://search.macaulaylibrary.org/catalog?taxonCode=baytan3&mediaType=photo -- which we can

age by the molt limits between the greater coverts and primary coverts. I don't

see any birds in Macaulay or in the photos Andre Moncrieff sent me from the

LSUMZ that look like definitive males with mixed features. The clean, geographically

narrow cut-off, combined with no morphological evidence for hybridization in a

species with seemingly high dispersal and with migratory populations, makes me

ok with voting yes. But, of course, finding and studying a contact zone and a

molecular study would help us out a lot in understanding systematics in this

taxon.”