Proposal (1017) to South

American Classification Committee

Treat (A) Dubusia

carrikeri and (B) Dubusia stictocephala as separate species

from Dubusia taeniata

Note: This is a

high-priority issue for WGAC.

Background: This is a long-standing, well-known

problem. Our SACC note on this is as

follows:

25. The subspecies carrikeri of the Santa Marta Mountains was

described as a separate species from Dubusia taeniata, but was treated

as a subspecies of the latter by Meyer de Schauensee (1966) and most subsequent

authors. The southern subspecies stictocephala, described as a separate

species and treated as such by Chapman (1926), was treated as a subspecies of D. taeniata by Hellmayr (1936) and

subsequent authors. Vocal differences

between it and nominate taeniata are

pronounced (Robbins et al., unpubl. data).

SACC proposal to

elevate stictocephala to species rank

did not pass. Del Hoyo et

al. (2016) treated all three as separate species.

Fifteen

years and 625 proposals ago, we voted down by only 1 vote (5-4 to split) a

proposal to split stictocephala from taeniata, and all the NO’s

were based on lack of published analysis:

Proposal (392) to South American Classification

Committee

Elevate Dubusia taeniata stictocephala to species level

The

Buff-breasted Mountain-Tanager (Dubusia taeniata) is a polytypic species

found from the northern end of the Andes south to southern Peru, with an

isolated population in the Colombian Santa Marta mountains (Paynter and Storer

1970, Isler and Isler 1987). The nominate

subspecies (type locality “Santa-Fé-Bogota” Colombia) ranges from western

Venezuela south to northern Peru, north and west of the Marañón low. The distinctive blue-crowned stictocephala

(type locality in Junín, Peru) occurs from south and east of the Marañón low to

southern Peru (Schulenberg et al. 2007).

The Santa Marta birds, carrikeri, have some blue crowned

streaking, unlike solid, blackish-crowned nominate, with the buff of the breast

extending up to the center of the throat (depicted in Isler and Isler

1989).

All three subspecies were originally described as species. Hellmayr (1936) treated stictocephalus

as conspecific with taeniata, and Meyer de Schauensee (1966) treated carrikeri

(described after Hellmayr 1936) as conspecific with taeniata. Those treatments have been followed by all

subsequent authors (Paynter and Storer 1970, Isler and Isler 1987, Ridgely and

Tudor 1989, Schulenberg et al. 2007). In

October 2008, Hosner (Xeno-canto America, XC29739) and Robbins (MLNS 137644; note that the first 5-6 notes are under natural conditions, whereas

the final 25 are after playback) independently recorded singing Dubusia

in Junín, Peru, just south of the type locality for stictocephala. Upon returning from the field they compared

their recordings with songs from a number of other localities throughout the

species’ range and determined that the Junín birds sounded very different from

birds north of the Marañón (multiple cuts on Xeno-canto and Macaulay Library

of Natural Sounds, Cornell University web sites). Moreover, Lane had recorded

birds (Xeno-canto America, cuts XC29538-9539) in October 2004 just south of the

Marañón at Leimebamba, Amazonas, Peru, that match the vocal type from

Junín. Birds just to the west and north

of the Marañón give the typical nominate song (Ted Parker recordings from Cerro

Chinguela, Cajamarca, and Huancabamba, Piura, Peru; MLNS, 21793, 21953).

As can be

readily heard and visualized spectrographically on both the Xeno-canto America

and MLNS web-sites, the song of nominate consists of 2-3 loud, whistled notes,

“feeeeu-bay” or “feeeeu-feeeu-bay” (Ridgely and Tudor 1989). The first two

notes slur downward in frequency, with the third note (when given) having less

of a frequency change. This song is consistent throughout the range of nominate

(both east and west slopes), and according to Nick Athanas and Niels Krabbe

(pers. comm.) the Santa Marta carrikeri also has a song similar to

nominate. Birds continue to give this

song-type even after playback (Paul Schwartz recordings from Venezuela; MLNS 70755-70756-70757). In striking contrast, stictocephala’s

song is quite distinct from birds north of the Marañón, and is reminiscent of a

Pipreola’s thin, high-pitched whistle. This song is a single-noted

whistle that is sharply slurred downward in frequency. The single-noted song is

continually repeated and is given at dawn as well as later in the morning and

after playback (MLNS 137664).

Because of

the dramatic break in song and plumage across the North Peruvian/Marañón low,

we recommend that stictocephala be elevated to species status. Although

the specific epithet signifies the crown is spotted, this region and the nape

are actually heavily streaked with cerulean color. To reflect this distinctive plumage character,

we recommend Cerulean-streaked Mountain-Tanager as the English name for D.

stictocephala. As a final comment,

we suspect that genetic data will further corroborate the Marañón break, and

may even demonstrate considerable differentiation among nominate and carrikeri,

despite the fact that these latter two taxa reportedly have similar voices.

Acknowledgments.

Nick Athanas and Niels Krabbe kindly shared their knowledge about the

vocalizations of carrikeri. Greg

Budney and Jessie Barry at MLNS kindly made available on-line key cuts of Dubusia.

Literature

Cited.

Isler, M.

L. and P. R. Isler. 1987. The tanagers. Natural history,

distribution, and identification.

Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

Meyer de

Schauensee, R. 1966. The species of

birds of South America and their distribution.

Livingston Publishing Company, Narbeth, Pennsylvania.

Paynter, R.

A., Jr. and R. Storer. 1970. Check-list of birds of the

world. Museum of Comparative Zoology, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Ridgely, R.

S. and G. Tudor. 1989. The birds of South

America. Vol. 1. The oscine passerines. University of

Texas Press, Austin.

Schulenberg,

T. S., D. F. Stotz, D. F. Lane, J. P. O’Neill, and T. A. Parker,

III. Birds of Peru. Princeton University Press,

Princeton, New Jersey.

Mark B. Robbins, Pete A. Hosner, and Dan F. Lane, March 2009

____________________________________________________________________

Comments

from Cadena: “NO, for a lack of published analyses.”

Comments

from Nores: “NO. Yo estoy de acuerdo con Cadena de no aceptar cambios de

este tipo que no estén apoyados por análisis publicados. Además no veo que haya

un “dramatic break in plumage across the Peruvian Marañón low”. Las diferencias para mi son propias de

subespecies.”

Comments

from Remsen: “NO, but only on a technicality. I understand the frustration

when vocal differences are known and now readily assessed by means of online

recordings. However, I favor sticking to

our policy of making changes based only on published analyses and comparisons

of those recordings. Note that the above

proposal needs only a little more work to be ready for submitting as a short

publication. Just the process of putting

together existing information as a SACC proposal represents the bulk of the

work needed to get a short publication submission-ready. In other words, a proposal sufficiently

detailed and rigorous to pass SACC is also very close to publishable as a

journal note.”

Comments

from Zimmer: “NO. My feelings about this proposal are similar to those

of the preceding one (Troglodytes aedon/cobbi). I think Mark, Pete and Dan make an excellent

case for splitting these birds, and that ultimately, this will be shown to be

the correct course. But again, given

that the SACC has generally maintained a policy of requiring some sort of

published analysis before making a change, I reluctantly vote NO. If Mark and company could publish even a

short paper with spectrographic examples of the vocal differences, I would

happily change my vote.”

Comments

from Jaramillo: “YES – Although I do think the authors should publish a short

note, the vocal difference seems to clear to me and the data so readily

accessible that I feel more at ease making this change than letting it sit. It

seems to me that there are too few researchers, and even less time for them to

do these types of things than we have open questions. However, I dislike the

English name; it doesn’t quite roll of the tongue.”

Comments

from Schulenberg: “YES. I'm with Al on this one. In the past, I've voted against

any number of good-sounding proposals because of the lack of a "published

analysis." But we've let a lot of decent ideas die along the way - many of

which have yet to be written up for publication, years later - and in the

meantime it's becoming easier and easier to assemble the relevant information

online.

“I see some

room, in other words, between "field guide taxonomy" (little or no

documentation provided) and a Kevin Zimmer 30-page exhaustive survey. The point

of a published analysis, after all, is in spreading and sharing data and the

conclusions that stem from them. I think this proposal follows in the vein. If

we agree that the authors convince *us* of the merits of their case, and if the

data on which we base our conclusions are available to others, then we're only

hurting ourselves by voting against it.

“The name

"Cerulean-streaked Mountain-Tanager" is awkward, however. Can't you

settle for "Blue-streaked Mountain-Tanager"? A four-word name (long!)

with a four (!!) syllable opener is too much for me. Simplify, simplify.”

Comments

from Stotz: “YES. This looks like a clear split. I agree with Jaramillo and Schulenberg that

Cerulean-Streaked Mountain-Tanager is a bit too much. Tom’s suggestion of Blue-Streaked Mountain-Tanager

sounds good to me.”

Comments

from Stiles: “NO for now, for exactly the same reasons as in the previous

proposal: a peer-reviewed publication

should be required – especially for people like me who are unfamiliar with the

taxa concerned.”

Comments

from Pacheco: “YES. Voto sim pelas mesmas razões apresentadas na Proposal

#391. Creio ser mais danoso – mascarando a real diversidade – manter táxons

“agrupados” meramente por tradição/continuísmo do que tratá-los como distintos

até que alguma análise corrobore o contrário.”

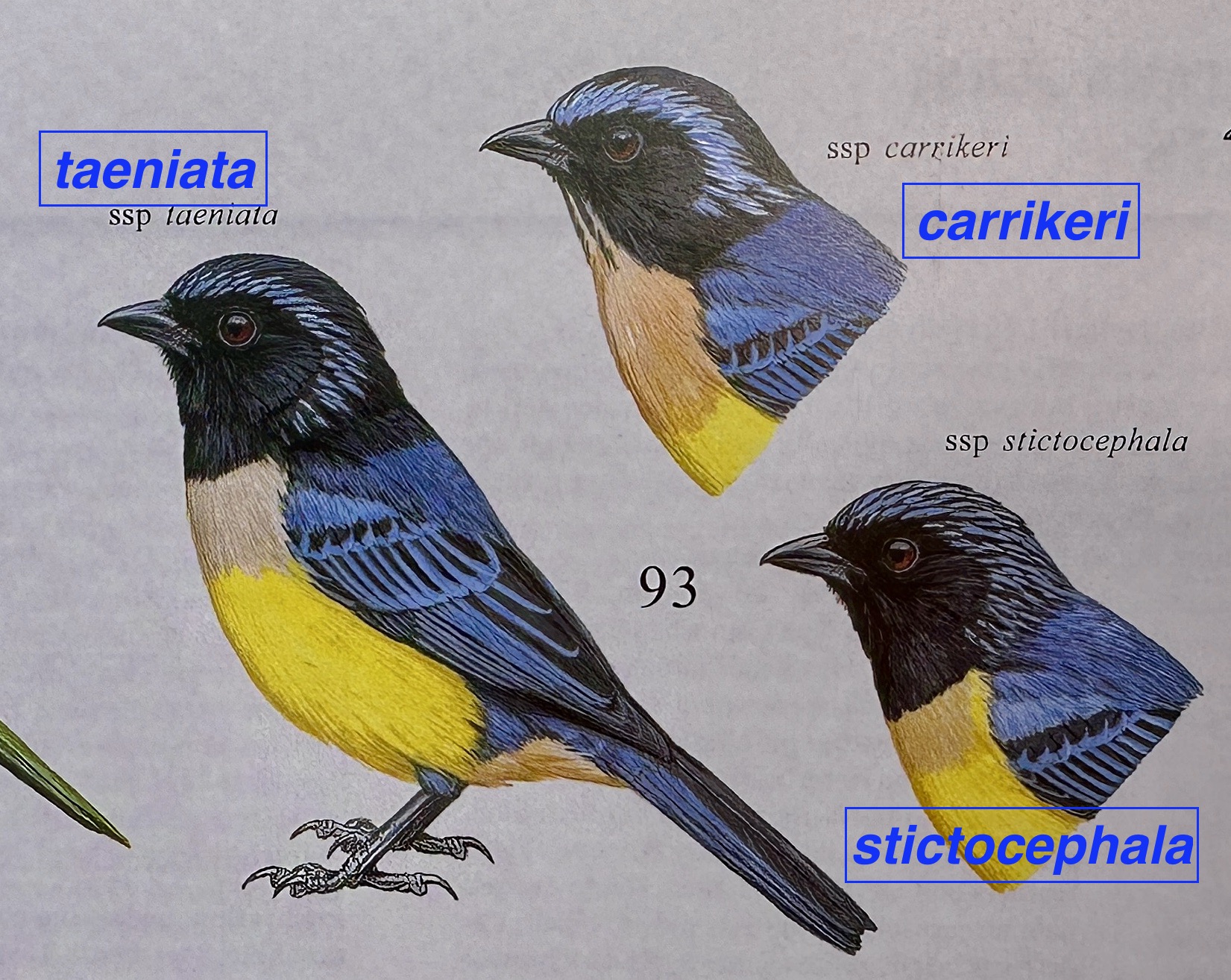

Three

taxa are involved, and they show a classic pattern of Andean cloud-forest bird

distribution: two taxa from the main Andes separated in northern Peru by the

North Peruvian Low/Marañon plus a peripheral isolate in the Santa Martas:

D. t. carrikeri – Santa Marta

Mountains

D. t. taeniata – northern Andes (nw.

Venezuela and Colombia south to n. Peru)

D. t. stictocephala – southern Andes (n.

Peru in Amazonas to s. Peru in Cuzco)

Here

is Hilary Burn’s plate from HBW (Hilty 2011):

New

information:

Del

Hoyo & Collar (2014) treated as a separate species based on the Tobias et

al. point scheme as follows (provided by Pam Rasmussen):

“Buff-breasted: https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/historic/hbw/bubmot3/1.0/introduction

Hitherto (apart

from at their original description) treated as conspecific with D. carrikeri

and D. stictocephala.

Monotypic.

“Carriker's:

https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/historic/hbw/bubmot4/1.0/introduction

Hitherto (except when first described)

treated as conspecific with D. taeniata and D. stictocephala, but

differs

from both in its denser blue streaking on

forehead and eyebrow, forming a near-complete supercilium (2);

buff vs black chin, throat and upper breast

(3); and further from taeniata in its green-tinged dull dark blue vs

matt black central crown to mantle and back

(3); plus higher frequencies in song (3) (1); and further from

stictocephala in its green-tinged dull dark

blue vs dull grey-blue mantle and back (1); plus song consisting of

2–4 whistles instead of single whistle (3).

Monotypic.

Their

vocal analysis comes from Boesman (2016l), who found substantial

differences among the three taxa:

“Song of the other two races consists of

2-4 whistles, in carrikeri

the last whistle is markedly higher-pitched, while in taeniata the last

whistle is actually the lowest-pitched.

“We can quantify these vocal differences

as follows:

“Stictocephala is unique in having a song consisting of a single

whistle (vs

typically 2-4 in other races)(score 3) and by singing at much higher

frequencies (min. frequency > 6.5kHz vs

typically down to 3-5kHz)(score 2). Application of Tobias criteria would lead

to a total vocal score of about 5.

“Carrikeri (n=4) can further be distinguished from taeniata by reaching

much higher frequencies (score 3).”

See

Boesman for sonograms, and also check recordings at xeno-canto and

Macaulay. I can see and hear the

differences outlined above.

Discussion

and Recommendation:

What we have here is yet another classic case of trying to apply BSC species

limits to phenotypically differentiated allotaxa. The question for me, always, is …. “have

these taxa diverged to the point associated with known species-level

differences in the family?” To answer

that properly, what we really need is a batch of “knowns” in terms of sister

taxa that are parapatric with and without free gene flow so that we can

extrapolate from those “knowns” to the “unknowns” … for better or worse. This is the classic “yardstick” approach,

which has obvious problems due to the idiosyncrasies of evolution. The only other options are to apply an

arbitrary degree of genetic differentiation, also based on published “knowns”, but

that has the classic intellectual problem of where to draw the line. Another is to apply PSC rationale in terms of

phenotypic diagnosability, but in my published opinions, this defines the

subspecies rank, not necessarily the species rank. A currently popular solution, at least in

terms of titles of papers, is what is being called “integrative taxonomy”. The label sounds wonderful, but how are the

different kinds of data supposed to be “integrated”? This approach as far as I can tell involves a

subjective evaluation of different data-sets with unknown weights given to

each. When they all the data line up,

one way or another, we are comforted. We

actually use this approach generally on SACC in our evaluations, but with vocal

differences heavily weighted for most groups.

What

matters to tanagers in terms to barriers to gene flow? Detailed characterizations of contact zones

and gene flow in tanagers to provide our “knowns” are very few. I don’t have time to compile and synthesize

these, but I would start with Diego Cueva’s studies of the Thraupis episcopus/sayaca complex.

So,

with that long-winded preamble, what do we do here? We rejected the 2009 proposal because of lack

of published data on voice. Now we have

that. Although not peer-reviewed (and

N=4 for carrikeri), it is nonetheless published, and Boesman’s analysis

documents the vocal differences between nominate taeniata and stictocephala

that were described in the original proposal by Mark, Pete Hosner, and

Dan. In my opinion, this represents

sufficient evidence for placing burden-of-proof on a single species taxonomy,

so I recommend a YES on this one.

English

names:

BirdLife International used “Streak-crowned” for stictocephala and “Carriker’s”

for carrikeri, and retained parental “Buff-breasted” for taeniata. I think we need a separate proposal on this

because by our guidelines, the parental name should not be used to prevent

confusion with a previous classification because the distributions of stictocephala

and taeniata are not strongly asymmetrical. Something like “Buff-chested” might do the

trick by retaining the connection to the old name and slightly more accurately

describing the distribution of the buff (although not to the exclusion of stictocephala). “Carriker’s” is highly appropriate. No ornithologist’s name is more directly

associated with the Santa Martas (e.g. Todd and Carriker, 1922, Birds of the

Santa Marta Mountains, Annals Carnegie Museum, 611 pages),

and this is something that bird people should be interested in knowing. See David Weidenfeld’s and Storrs Olson’s tributes, and also

Wiedenfeld’s paper on Carriker in Bolivia. Because SACC is no longer associated with

AOS, any constraints eponyms has been removed, and HBW/BLI has been using

“Carriker’s” for 8 years. Carriker lived

in the Santa Martas, and his son was on born there; his son wrote an excellent

book on his time there (“Vista Nieve: the Remarkable True Adventures of an

Early Twentieth-Century Naturalist and his family in Colombia [aka “Columbia”

fide Amazon Inc. book ad], South America” by M. R. Carriker, 2001). This would be the first English name to honor

him; he has one honorific species name, Grallaria carrikeri.

References: (see SACC

Bibliography

for standard references)

Boesman, P. (2016l). Notes on the vocalizations of

Buff-breasted Mountain-tanager (Dubusia

taeniata). HBW Alive Ornithological Note 403. In: Handbook of the

Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow-on.100403

Van Remsen, July 2024

Vote tracking chart:

https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart968-1043.htm

Comments

from Robbins:

YES. Of course I vote for splitting taeniata

and stictocephala because of the striking differences in primary song,

as we detailed years ago. The differences in vocalizations between those two

are greater than carrikeri is from nominate. However, carrikeri is the

most unique in plumage among the three in not having a complete black throat

and having the buff of the chest extending into the throat and further down the

chest. So, accounting for those differences, I support recognition of stictocephala

and carrikeri as species.”

Comments from Areta: “YES. I am on the fence with

this one. Plumage and vocalizations clearly serve to recognize three clusters

of variation that coincide with well-known biogeographic breaks, but I am not

totally convinced that these clusters need to be afforded species status. We

know little about how these birds acquire their songs and how they use them,

which would be important to assess the biological meaning of these differences.

There is also amazing variation in the vocalizations of the taeniata group, which defies

a simple song characterization. So, yes, there are three clusters that have

been isolated for some time (or so it seems) based on the accumulation of minor

plumage differences and vocal distinctions (regiolects?), but no evidence on

the effect of these differences and no genetic/temporal framework in which to

fit these differences. I vote YES to the split, but I am

certainly hungry for more compelling evidence.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“YES. The vocal difference between taeniata and stictocephala seems solid (if

not published in a journal, the recordings are publicly available); carrikeri

has the most divergent plumage. For E-names Streak-crowned is a simpler but

descriptive name for stictocephala and Carriker’s a just recognition for

carrikeri; for taeniata, Buff-banded might be preferable: the

buff is really a band, not the entire chest (though equally valid for stictocephala,

this species is already accounted for with Streak-crowned).”

Comments

from Lane:

“YES. I think the voices and plumages of the three taxa are distinctive enough

to warrant splitting.”

Comments

from Claramunt:

“YES. This is a relatively straightforward case. Clear-cut plumage differences

in more than one trait matching clear-cut differences in songs. The evidence

for the split is now published. They were described as different species. Where

is the evidence for conspecificity? Hybrids zones, intermediate birds? Nowhere.

Just a subjective judgment of similarity, the faulty approach of the polytypic

lumping craze.”

Comments

from Steve Hilty (voting for Del-Rio): “YES. Raising

the three races of Dubusia taeniata to species level certainly

seems warranted. Vocal info for stictocephalus especially clear and

mirrored in dozens of other taxa that break at the Marañon—a little surprising

that this wasn't done with the first (#392) proposal. Song of carrikeri

is closer to taeniata but obviously different—song differences

noted in my 2021 Birds of Colombia. Also note plumage differences, and

geographic isolation. Boesman confirms vocal differences of carrikeri,

which are particularly evident in field.”

Comments

from Glenn Seeholzer (voting for Jaramillo): “YES. Biogeographically discrete,

concordant variation in plumage and song places the burden of proof on the

one-species hypothesis. As others have pointed out, the cherry on top is that

all three were originally described as distinct species. We’re just shooting

ourselves in the foot if we demand a higher level of analysis to resurrect

these taxa as species than was employed by Hellmayr and de Schauensee to lump

them.

“I’ve

created three galleries of ML audio assets for each taxon to help us better

visualize the differences described by Boesman and others; carrikeri, taeniata, stictocephala. The song of taeniata,

while variable in the number of notes (2-4), is always between 4-6 kHz. The

single down slur of stictocephala starts around 10 kHz and descends to 7

kHz. The two-note song of carrikeri contains an introductory note

between 4-6 kHz followed by a down slurred note starting at 9.5 kHz and ending

at 6 kHz. It seems like carrikeri combines the low frequencies of stictocephala and

with the high frequencies of taeniata. Not sure that suggests any specific

phylogenetic relationship, more likely it's just evolution’s random walk but it

will be interesting to know what genetic data tell us about the phylogenetic

relationships among these taxa. Regardless, that shouldn't stop us from

considering them distinct species.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“YES to A and YES to B. As should be apparent from my comments on

Proposal #392, my feelings at the time were that I thought splitting out stictocephala

would ultimately prove the correct course, and that I was only voting “No”

because of a lack of any published analysis to prop up the split. Now we have an analysis (Boesman 2016l), and

although the sample size for carrikeri is only n=4, I think the burden

of proof now shifts to those who would continue to advocate for a one-species

treatment.”