Proposal (1019) to South

American Classification Committee

Treat Granatellus

paraensis as a separate species from G. pelzelni

Note: This is a

high-priority issue for WGAC.

Background: Our new SACC note on this is as follows:

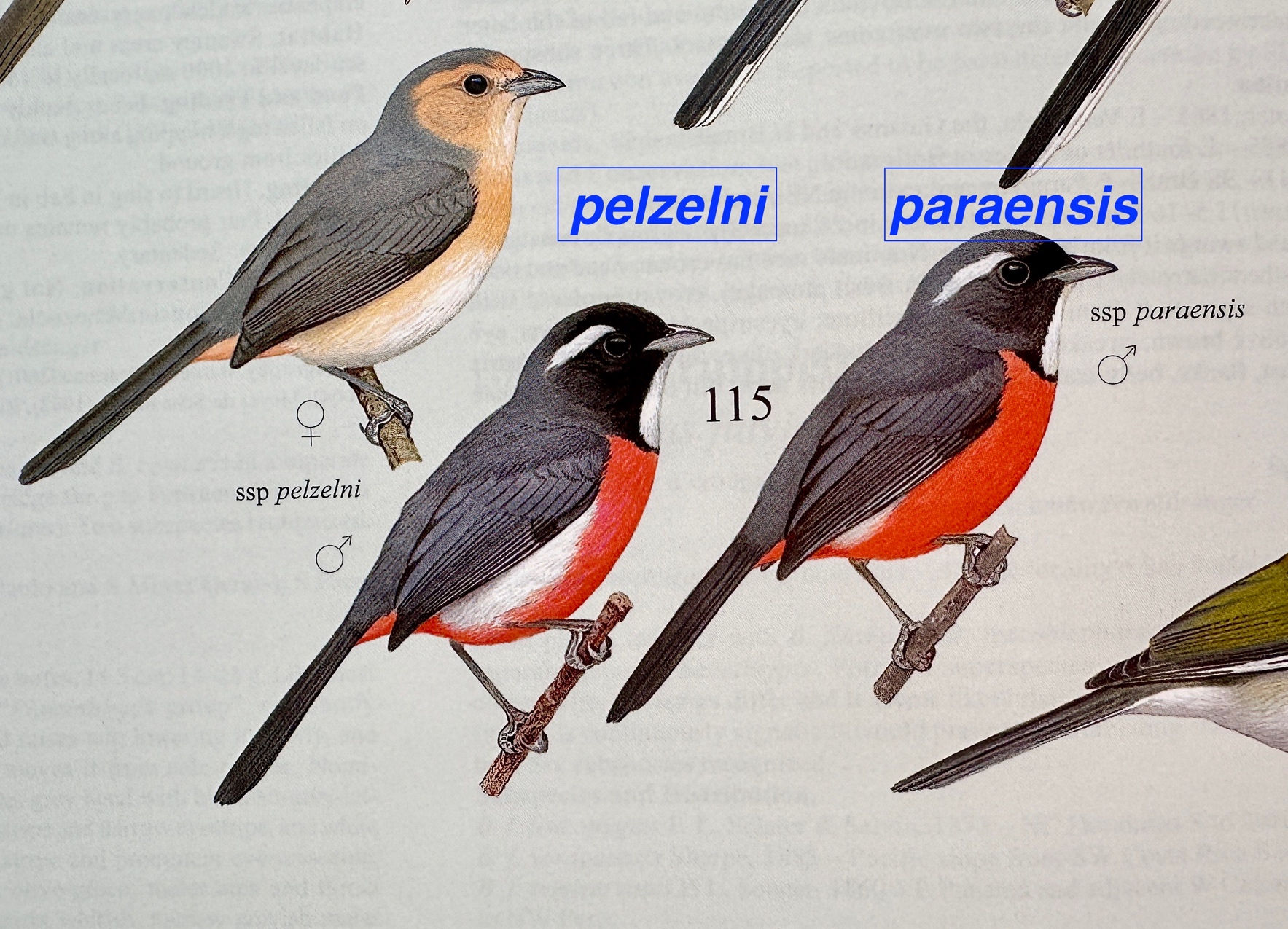

34a. Del Hoyo & Collar (2016) treated the subspecies paraensis

of se. Amazonia as a separate species (Rose-bellied Chat), based in part on

vocal differences from nominate pelzelni described by Boesman (2016n).

Here

is the basic set-up. Granatellus pelzelni is considered to consist of

two subspecies:

• nominate pelzelni:

largely at the periphery of the Amazon Basin from e. Colombia, c. Venezuela,

the Guianas, ne. Brazil and then S of the Amazon River in central Brazil, W of

the Rio Tocantins, to e. Bolivia

• paraensis: E

of the Rio Tocantins in extreme e. Brazil.

They differ in the

extent of white on the flanks and the amount of black in the face and

crown. Here’s the plate by David Quinn

from HBW:

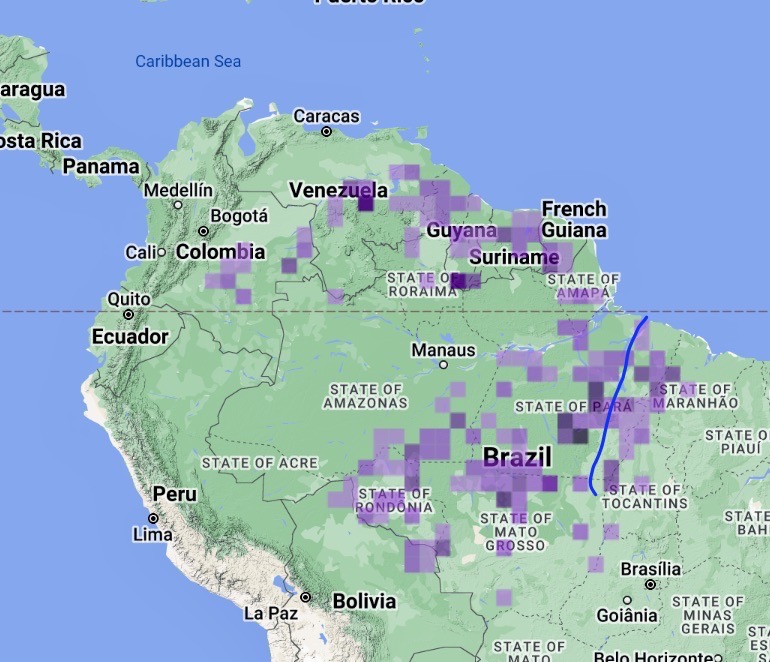

The peculiar and patchy

geographic distribution is best understood visually – here is the eBird map,

onto which I placed a blue line to roughly represent the Tocantins.

Where

it gets fuzzy for me because I am not familiar with the area is which

localities go with which taxon in the upper Tocantins, Also, the possibility seems strong to me,

again keeping in mind I am unfamiliar with the region, that there could well be

a contact zone in the headwaters of the Tocantins-Araguaia river basin in

southern Tocantins and northern Goias that would be extremely informative.

New

information:

Del

Hoyo & Collar (2014) treated as a separate species based on the Tobias et

al. point scheme as follows:

"Rose-breasted Chat

(Rose-bellied)

“Hitherto

treated as conspecific with G.

pelzelni, but differs in its grey vs black mid-crown and ear-coverts (2);

lack of white flanks (pink extending further onto them or perhaps more grey

extending out from inner flanks) (2); distinctive song, a variable, rather

rhythmic phrase alternating one or more mellow low-pitched down-slurred

whistles and harsher short high-pitched notes, vs a series of repeated rather similar

notes, sometimes ending with a different trilled part or two series of repeated

notes, to be scored as fewer repeated notes (2), shorter song phrases (ns[2]),

different note shapes (ns[1]) and mellow notes having a much narrower frequency

range (2); and possible absence (not yet recorded) of the typical “jrt” call of

G. pelzelni (ns[2])

(2). Monotypic.”

The

vocal data come from Boesman (2016n), who stated:

“A

comparison of song (illustrated with multiple sonograms in the pdf version of

this note): nominate (in the Guianas, N of Amazon), nominate (S of Amazon) and

paraensis (n=4).

“There

is a striking difference in song between paraensis

and nominate! Nominate in all regions (N and S of Amazon) has a song consisting

of a series of repeated notes which are all rather similar-shaped (sometimes

ending with a different trilled part or 2 series of repeated notes). Typically

6-15 repeated notes. Phrase length 1.8 - 3s. Notes have a freq. range of c. 0.7

- 3kHz. Paraensis seemingly

has a song which is a variable, rather rhythmic phrase with alternating a

mellow low-pitched down-slurred whistle (or a short series of these) and

harsher short high-pitched notes. Repeats 1 - 6. Phrase length 0.5 - 1.5s.

Mellow notes have a narrow frequency range of c. 0.7 - 1.1kHz.

The

vocal difference can be scored based on paraensis

having less repeated notes (score 2-3), shorter song phrases (score 2-3) and

different note shapes (1-2) , with mellow notes having a much narrower freq.

range (2), which leads to a total vocal score of about 5. This obviously is

based on only 4 examples of paraensis,

and thus needs further confirmation, but nevertheless seems quite

convincing.

With

just N=4 in Boesman’s analysis of paraensis, I would object in principle

to making any taxonomic conclusion on these putative song differences. In my opinion, Boesman’s “needs further

confirmation” statement is correct. Just

from checking recordings in Macaulay, I noticed this one:

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/220845741 (by Ciro Albano

Tocantins, from the Rio Javaés, a right bank tributary of the R. Araguaia,

which itself is a left bank tributary of the Tocantins. This is classic pelzelni song with its

evenly spaced set of upward-inflected notes.

It is west of the Tocantins itself, so if the Tocantins is the barrier,

then it fits that pattern, but the Araguaia is actually bigger than the

Tocantins, so again I want to know (1) is it the Tocantins itself that is the

barrier or the Tocantins drainage? And (2) what did this individual look

like. It is identified as paraensis

in Macaulay, but the basis of this uncertain.

For

reference, here’s one that fits Boesman’s characterization of paraensis

(by Alex Aleixo, Pará at Municipio de Tomé-Açu) from Pará, east of the

Tocantins:

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/219437

New

genetic data:

I had originally overlooked the published genetic data on Granatellus in

this region. Alex Aleixo alerted me to

his paper (Dornas et al. 2022), which included the two taxa of Granatellus

in their analysis of genetic variation in the Tocantins drainage. See Areta comments below for full citation

and description of the data There is a

strong genetic break between the two taxa, and the Tocantins is the barrier,

with a 5.3% sequence divergence. But

before anyone gets excited about that, here goes more than my usual diatribe on

genetic distances as a metric for taxon rank.

Below

are comparisons of genetic distance (ND2) between 62 taxon pairs that are in

contact or approach each other in the Rio Branco region studied by Luciano Naka

for his dissertation here at LSU. This

remains as far as I know the largest comparative data set of its kind, and note

that because they were all done by the same methodology using the same genetic

markers on “sedentary” tropical birds, mostly forest-dwellers, this controls

for several potential sources of variation.

I am going to keep using this table every time genetic distance is used

in our assessments of species rank. Note

also the within-family variation – I see no evidence for a phylogenetic

effect. To no one’s surprise, taxa we

rank as species on average show greater between-taxon genetic distance. That is not in dispute. But note that the ranges overlap widely. Just within this sample, if forced to use

genetic distance alone as a metric, any GD measure between 2.0 and 13.0% cannot

be used as a diagnosis for species rank.

What if the sample were expanded beyond sedentary Amazonian birds? Certainly, those ranges would expand in both

directions, but especially downwards, below 2.0%. Some degree of taxonomic circularity

may be biasing this analysis, and Naka et al. rightfully advocated for closer

examination of some of the taxon pairs currently ranked as subspecies. Nevertheless, at this point, the general

signal from genetic distance data is that it cannot be used as a means of

assigning species vs. subspecies rank, as emphasized by Naka et al.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

|

Data from Naka et al., 2012, Am. Nat. 179: E115-E132, Table1) |

|||||||

|

Taxon A |

Taxon B |

rank |

Gdist |

species |

subspecies |

species + SU/SP |

subspecies - SU/SP |

|

Hylophilus ochraceiceps luteifrons |

H. o. ferrugineifrons |

SU/SP |

13.3 |

13.3 |

13.3 |

||

|

Zimmerius acer |

Zimmerius gracilipes |

SP |

12.9 |

12.9 |

12.9 |

||

|

Pheugopedius c. coraya |

P. c. griseipectus |

SU |

12.9 |

12.9 |

12.9 |

||

|

Tyranneutes virescens |

Tyranneutes stolzmanni |

SP |

11.3 |

11.3 |

11.3 |

||

|

Hylophilus muscicapinus |

Hylophilus hypoxanthus |

SP |

11.3 |

11.3 |

11.3 |

||

|

Phaethornis s. superciliosus |

P.s. insolitus |

SU |

10.8 |

10.8 |

10.8 |

||

|

Willisornis p. poecilinotus |

W. p. duidae |

SU |

10.8 |

10.8 |

10.8 |

||

|

Microcerculus b. bambla |

M. b. albigularis-caurensis |

SU |

10.1 |

10.1 |

10.1 |

||

|

Schiffornis t. turdinus |

S. t. amazonus |

SU/SP |

9.7 |

9.7 |

9.7 |

||

|

Myrmotherula guttata |

Myrmotherula hauxwelli |

SP |

11.3 |

11.3 |

11.3 |

||

|

Hypocnemis cantator |

Hypocnemis flavescens |

SP |

9.0 |

9.0 |

9.0 |

||

|

Iodopleura fusca |

Iodopleura isabellae |

SP |

8.8 |

8.8 |

8.8 |

||

|

Glyphorynchus s. spirurus |

G. s. rufigularis |

SU |

8.5 |

8.5 |

8.5 |

||

|

Veniliornis cassini |

Veniliornis affinis |

SP |

8.5 |

8.5 |

8.5 |

||

|

Monasa atra |

M. morphoeus |

SP |

8.5 |

8.5 |

8.5 |

||

|

Onychorhynchus c. coronatus |

O. c. castelnaui |

SU/SP |

8.2 |

8.2 |

8.2 |

||

|

Galbula d. dea |

G. d. brunniceps |

SU |

8.2 |

8.2 |

8.2 |

||

|

Terenotriccus e. erythrurus |

T. e. venezuelensis |

SU |

8.2 |

8.2 |

8.2 |

||

|

Pyrilia caica |

Pyrilia barrabandi |

SP |

7.8 |

7.8 |

7.8 |

||

|

Galbula a, albirostris |

G. a. chalcocephala |

SU |

7.7 |

7.7 |

7.7 |

||

|

Capito niger |

Capito auratus |

SP |

7.7 |

7.7 |

7.7 |

||

|

Topaza pella |

Topaza pyra |

SP |

7.6 |

7.6 |

7.6 |

||

|

Epinecrophylla gutturalis |

E. haematonota |

SP |

7.4 |

7.4 |

7.4 |

||

|

Euphonia cayennensis |

Euphonia rufiventris |

SP |

6.9 |

6.9 |

6.9 |

||

|

Lepidocolaptes a. albolineatus |

L. a. duidae |

SU |

6.9 |

6.9 |

6.9 |

||

|

Dendrocincla m. merula |

D. m. bartletti |

SU |

6.4 |

6.4 |

6.4 |

||

|

Xiphorhynchus guttatus polystictus |

X. g. guttatoides |

SU |

6.4 |

6.4 |

6.4 |

||

|

Xenops minutus ruficaudus |

X. m. remoratus |

SU |

6.3 |

6.3 |

6.3 |

||

|

Dendrocincla f. fuliginosa |

D. f. phaeochroa |

SU |

6.1 |

6.1 |

6.1 |

||

|

Thalurania f. furcata |

T. f. nigrofasciata |

SU |

5.7 |

5.7 |

5.7 |

||

|

Percnostola r. rufifrons |

P. r. minor |

SU |

5.4 |

5.4 |

5.4 |

||

|

Tolmomyias assimilis neglectus |

T. a. examinatus |

SU |

5.3 |

5.3 |

5.3 |

||

|

Xiphorhynchus pardalotus |

Xiphorhynchus ocellatus |

SP |

5.3 |

5.3 |

5.3 |

||

|

Hemithraupis f. flavicollis |

H. f. aurigularis |

SU |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

||

|

Thamnophilus amazonicus divaricatus |

T. a. cinereiceps |

SU |

4.3 |

4.3 |

4.3 |

||

|

Automolus infuscatus cervicalis |

A. i. badius |

SU |

3.7 |

3.7 |

3.7 |

||

|

Microbates collaris torquatus |

M. c. collaris |

SU |

3.0 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

||

|

Tolmomyias poliocephalus sclateri-klagesi |

T. p. poliocephalus |

SU |

3.0 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

||

|

Myrmothera c. campanisona |

M. c. dissors |

SU |

2.8 |

2.8 |

2.8 |

||

|

Pteroglossus aracari |

Pteroglossus pluricinctus |

SP |

2.8 |

2.8 |

2.8 |

||

|

Cymbilaimus l. lineatus |

C. I. intermedius |

SU |

2.7 |

2.7 |

2.7 |

||

|

Myrmoborus myotherinus ardesiacus |

M. m. elegans |

SU |

2.7 |

2.7 |

2.7 |

||

|

Momotus m, momota |

M. m. microstephanus |

SU |

2.3 |

2.3 |

2.3 |

||

|

Gymnopithys rufigula |

Gymnopithys leucaspis |

SP |

2.3 |

2.3 |

2.3 |

||

|

Dendrocolaptes c. certhia |

D. c. radiolatus |

SU |

2.1 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

||

|

Brotogeris chrysoptera |

Brotogeris cyanoptera |

SP |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

||

|

Piculus f. flavigula |

P. f. magnus |

SU |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

||

|

Celeus u. undatus |

Celeus u. grammicus |

SU |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

||

|

Thamnophilus murinus cayennensis |

T. m. murinus |

SU |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

||

|

Cercomacra cinerascens immaculata |

C. c. cinerascens |

SU |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

||

|

Schistocichla l. leucostigma |

S. 1. infuscata |

SU |

1.9 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

||

|

Trogon r. rufus |

T. r. sulphureus |

SU |

1.9 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

||

|

Cercomacra tyrannina saturatior |

C. t. tyrannina |

SU |

1.9 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

||

|

Synallaxis rutilans dissors |

S. r. confinis |

SU |

1.7 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

||

|

Piprites c. chloris |

P. c. tschudii |

SU |

1.7 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

||

|

Sittasomus griseicapillus axillaris |

S. g. amazonus |

SU |

1.6 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

||

|

Tachyphonus s. surinamus |

T. s. brevipes |

SU |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

||

|

Pithys a. albifrons |

P. a. peruvianus |

SU |

1.3 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

||

|

Hemitriccus zosterops rothschildi |

H. z. zosterops |

SU |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

||

|

Myrmotherula a. axillaris |

M. a. melaena |

SU |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

||

|

Celeus t. torquatus |

C. t. occidentalis |

SU |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

||

|

Celeus e. elegans |

C. e. jumanus |

SU |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

||

|

mean corrected genetic distance |

5.6 |

7.7 |

4.8 |

8.1 |

4.4 |

|

range |

N |

|

|

species (SP) |

2.0-12.9 |

17 |

|

subspecies (SU) |

0.8-13.3 |

45 |

|

species incl. possible splits (SU/SP) |

2.0-13.3 |

20 |

|

subspecies excl. possible splits (SU/SP) |

0.8-12.9 |

42 |

|

SU/SP = taxa currently treated as subspecies but under active

investigation |

||

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

In

the case of these two Granatellus taxa, a genetic distance of 5.3% falls

very close the mean genetic distance of all taxa in Naka et al.’s analysis and

cannot be considered, in my opinion, relevant to taxon rank.

Discussion

and Recommendation:

Here

is an expanded view of the David Quinn plate so that you have a broader context

for comparisons of plumage among species in Granatellus:

The

basic plumage pattern in the genus is fairly conservative, with the differences

between paraensis and pelzelni (extent of white on flanks, cheek

color, and superciliary strength) also reflected in differences among the other

two species. As you can see, paraensis

is the extreme in terms of reduction of white flanks but otherwise does not

stand out.

I

don’t have a strong recommendation on this.

I will vote NO for now because of the small N of songs of paraensis

and Boesman’s cautionary statement. The

genetic data certainly suggest a barrier to gene flow. Terra firme taxa ranked as subspecies

frequently show that level of genetic distance across major rivers, although I

did not think G. pelzelni was a species for which a river would be a

barrier, likely because of my ignorance of habitat preference. Regardless, this seems to me to be a case in

which detailed characterization of phenotype distribution in the region of

potential contact is critical, especially towards the upper Tocantins. I suspect that more detailed mapping of vocal

and plumage characters will confirm species rank for these two, but I feel

uneasy about endorsing this without those data.

English

names:

BirdLife International used Rose-bellied Chat for paraensis and retained

parental Rose-breasted Chat for pelzelni s.s. Nominate pelzelni is considerably more

widely distributed, and so retention of the parental name with that taxon is in

line with our SACC guidelines on

English names. The similarity between the names might be

confusing to some but helpful in others in linking the two. The problem is that BOTH taxa have rose

breasts and rose bellies, and so I suspect many people would have a problem

remembering which is which. I suggest

that “Tocantins Chat” has some merit for paraensis because it refers to

its center of distribution in terms of the river and to a lesser extent to the

Brazilian state; also, this part of Amazonia has undergone major deforestation

and so the toponym might have some merit in terms of promoting conservation. On the other hand, if pelzelni

replaces paraensis on the west bank of the Tocantins, the attractiveness

of that name is diminished. In my

opinion, we should do a separate proposal on the English name if the proposal

passes.

References: (see SACC

Bibliography

for standard references)

Boesman, P. (2016). Notes on the vocalizations of

Rose-breasted Chat (Granatellus

pelzelni). HBW Alive Ornithological Note 384. In: Handbook of the

Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow-on.100384

Van Remsen, July 2024

Vote tracking chart:

https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart968-1043.htm

Comments from Areta: “I vote NO to the split.

Although there is a reasonable case for the split based on minor plumage

distinctions and deep mtDNA differentiation, there is conflicting vocal

evidence that I would like to see sorted before changing our taxonomy.

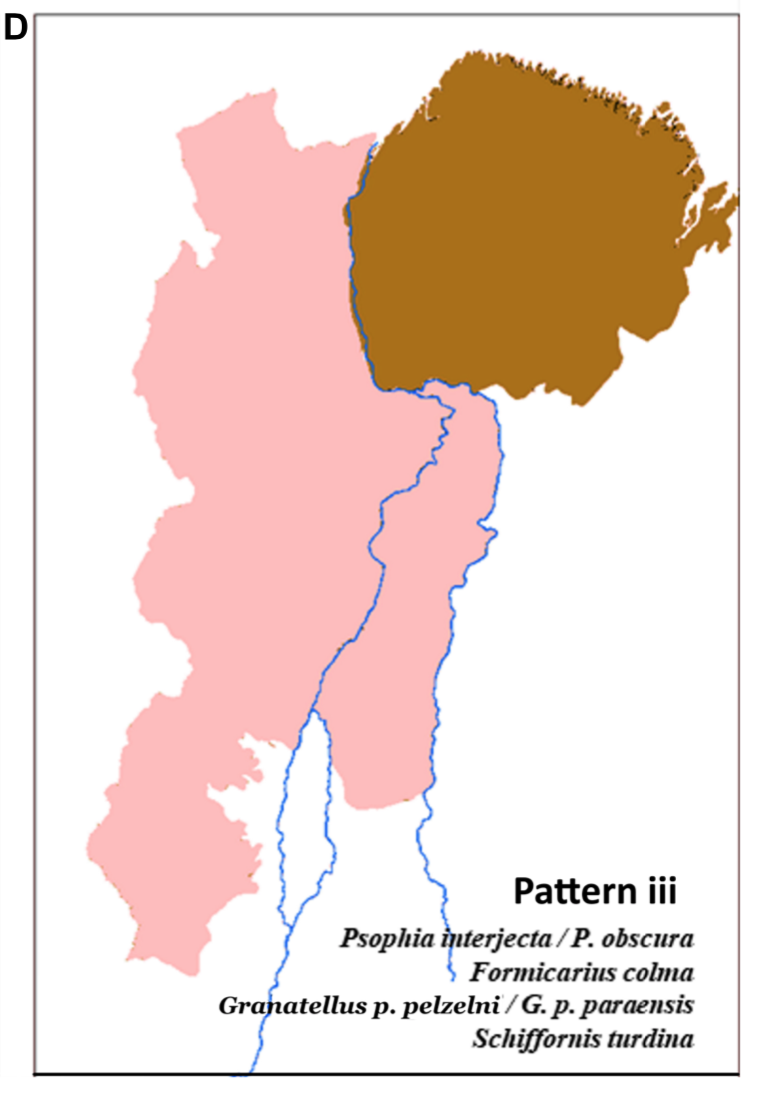

“Dornas

et al. (2022) sequenced 22 pelzelni (including the Guianan population)

and 2 paraensis. Terry Chesser downloaded 4 and 2 sequences and found

that mtDNA distance was 5.3%.

“Here

is Dornas et al´s figure 2D:

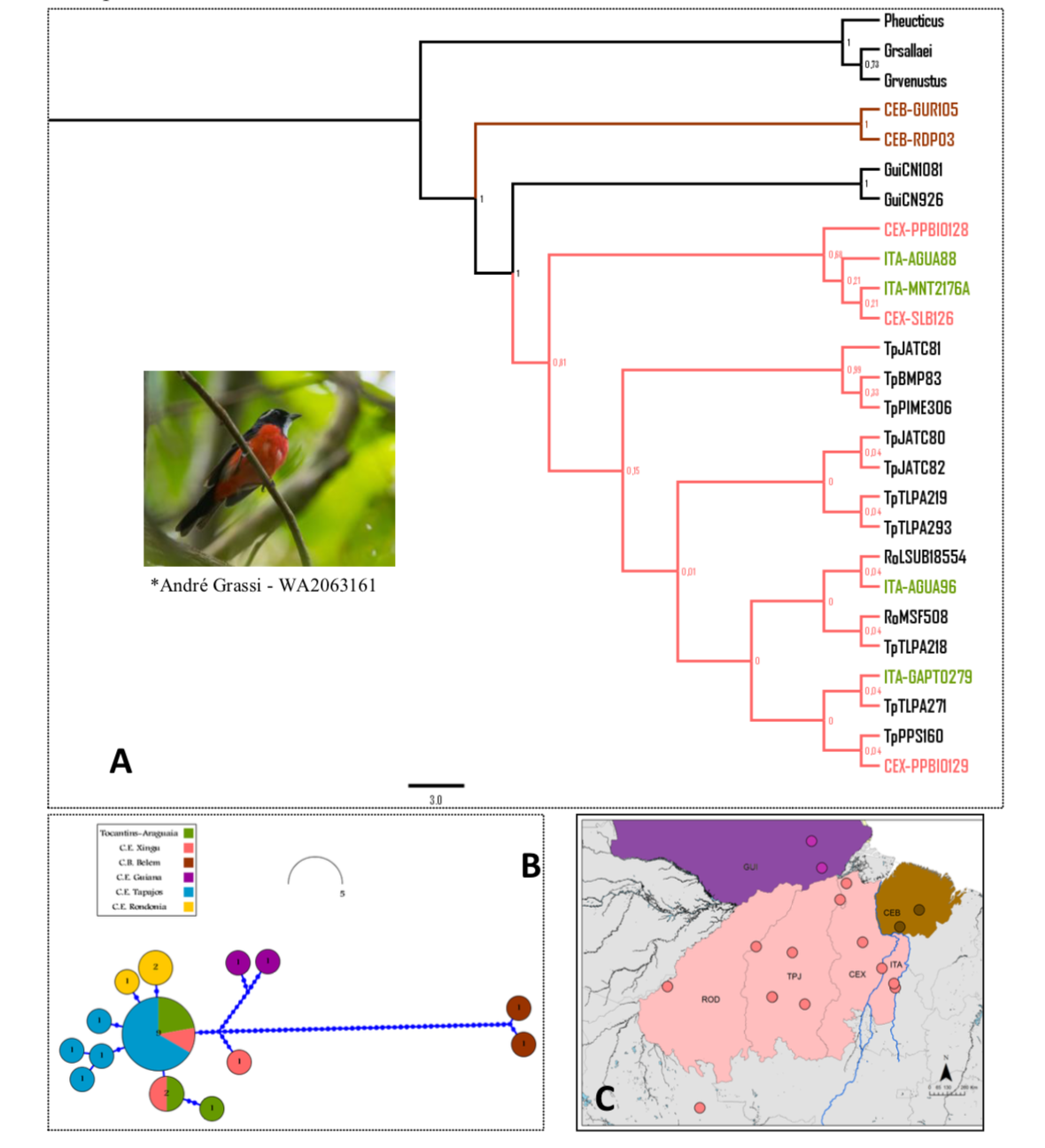

“And

their supplementary Figure S12: ‘Supplementary Figure 12. Phylogenetic tree (A) obtained by

Bayesian Inference (BI) for Granatellus pelzelni accompanied by

the respective haplotype network (B). Dots represent sampling localities within

our target area, with different colors denoting phylogenetic/haplotype

relationships among sampled individuals (C). From 24 sequenced individuals

(Table S2), a total of 14 haplotypes for the mitochondrial marker ND2 in 1033

bp fragments with the following base frequencies were retrieved: A = 0.3035, C

= 0.3643, G = 0.0991, T = 0.2332. As outgroup, sequences from Granatellus

sallaei (GB: EF529922.1), G. venustus (GB: EF529921.1) and

Pheucticus ludovicianus (GB: AF290108.1) were used. A total of 81

sites with nucleotide substitutions were identified. The evolutionary model

selected for BI by JMODELTEST was TRN+I (nst=6, rates=equal, pinvar=0.6100).

CEB = Belém Area of Endemism; CEX = Xingu Area of Endemism; and ITA = Tocantins

Araguaia Interfluve. Populations of Granatellus pelzelni

presented strong phylogeographic structure, with the occurrence of three

independent lineages: G. p. paraensis (BAE), G. p.

pelzelni (TAI and XAE and westward), and a third and apparently unnamed

lineage on the Guiana Area of Endemism (GAE). An asterisk (*) denote the photo

́s authorship along its accession number in the WikiAves (wikiaves.com; WA)

citizen science portal.’ “

Now,

I am confused by some recordings from Maranhão, where supposedly only paraensis

should be present. A recordist attached sex to two birds that were singing

together (and based on his comments, he seems quite familiar with the taxon paraensis,

to the point that he indicates that the females often give this song which

males never do). According to this, then the male paraensis would have a

song that is overall similar in structure to that of pelzelni, and not

radically different as Boesman (2016) indicated. However, I cannot rule out

that the recordings might have been misidentified, as most other recordings of paraensis

do follow Boesman´s description (certainly, all the ones in XC do so, as well

as those by Aleixo in the ML):

Male

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/194395401

[sounds quite similar to this one, from Pará,

west of the Tocantins river https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/375366741]

Female

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/194393221

Other recordings from eastern Pará:

Female?

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/214418071

Male?

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/194197101

“If

this interpretation is correct (I have seen Granatellus pelzelni a few

times, and maybe recorded it in SE Venezuela ages ago, but I do not claim

having a deep knowledge of this taxon), then the vocal differences need to be

reassessed, as clearly it is a weak basis to compare voices of males of one

taxon to females of the other one (although maybe only females of paraensis

give this multi-noted song?).

“The genetic break seems quite deep and abrupt,

but I would like to have more clarity on the situation with vocalizations.

There is a possibility that (vocally) Boesman might have compared pears to

apples. This does not explain the deep genetic break, but (if correct)

seriously undermines the vocal arguments. paraensis and pelzelni are presumably

allo/parapatric, but if one takes Boesman´s analyses as such, then the

recordings I point out above would indicate sympatry (alternatively, one can

interpret that the vocal differences are not as described and that both taxa

have structurally similar songs)..

“Dornas T, Dantas SM, Araújo-Silva LE,

Morais F and Aleixo A (2022) Comparative Phylogeography of Birds Across the

Tocantins–Araguaia Interfluve Reveals a New Biogeographic Suture in the Amazon

Far East. Front. Ecol. Evol. 10:826394. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2022.826394”

Comments

from Robbins:

“NO. Although the mitochondrial data suggest two

species, as Nacho points out there seems to be confusion on vocal comparisons.

The plumage differences may not be significant, note the differences between

nominate Granatellus venustus and G. v. francescae, where the

differences between those two are greater than those between the two pelzelni

taxa.

“Although I'm on the fence on this one, I would like to see

clarification on the vocalizations before voting Yes for recognizing paraensis

as a species.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“NO for now, for about the same reasons as for the Xenodacnis split, we

need a more thorough vocal analysis with definite data for the locations of the

birds recorded for a final decision. The plumage differences, to my eye, are of

the magnitude that better characterizes subspecies rather than species.”

Comments

from Del-Rio:

“YES. 5.3% mitochondrial divergence has to mean

something... I do not oppose "NO" votes... I agree that more data are

needed, but it's quite hard to find this level of mitochondrial divergence in

populations with similar geographic ranges...”

Comments

from Lane:

“NO. From the information provided in others’ comments above, it seems that

separating paraensis from pelzelni is poorly supported by

existing evidence. I would much rather wait for better evidence than act on

what little is available at present.”

Comments

from Claramunt:

YES. The birds look similar, but all Granatellus species look similar.

The fact is that paraensis differs from pelzelni in multiple

plumage traits. Songs seem to differ too, and mtDNA, although the sample size

is small, suggests substantial divergence.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“NO. I suspect something interesting

might be going on here, given the mitochondrial divergence and the plumage

differences, which, although relatively slight, are about on par with plumage

divergence in this genus, the members of which are mostly just small variations

on a common theme. However, I don’t think we have enough to go on at this point

to draw any definite conclusions.

Reading this Proposal, and listening to the vocal sample (ML219437, from

E of the Tocantins, by Alex Aleixo) that Van included in the Proposal, stirred

something from the distant past in my brain.

In August of 2007, Andy Whittaker and I spent a week surveying birds

based out of a logging camp in the Rio Capím region

(E of the Tocantins). I remembered

encountering Rose-breasted Chat there, and was pretty sure that I had tape-recorded

it. I just went back through my tape

logs from that trip, and a quick perusal turned up only a single recording of Granatellus,

which came at the end of a long sequence that began with Formicivora grisea,

and then switched to various species calling overhead from a mixed-species,

mid-level flock. At some point, with the

tape still running, I switched onto some repeated single-note calls, that may

have been from a Granatellus, but if so, sounded somewhat different from

what I am used to from nominate pelzelni. In any case, I then locked onto several songs

that are almost a perfect match for the Aleixo recording of paraensis,

and very similar to the ones labeled as “Female” and “Female?” that Nacho

shared from eastern Pará. I would

characterize these short, but variable (compared to typical repetitive series

given by nominate pelzelni) songs as suggesting a sweeter sounding

Dusky-capped Greenlet or the phrases of some vireo. Anyway, after recording several of these

songs, there is an obvious break in my recording, without a voice annotation,

followed by a long series of very excited sounding Granetellus

songs that are pretty typical to my ears, of songs given by nominate pelzelni. I recorded the Granatellus right down

to the end of Side B on the cassette, and barely squeezed in an annotation of

“Songs of Granatellus pelzelni, preceded by Formicivora grisea”

before the tape abruptly ran out. In

listening to the recording, it’s pretty obvious to me that I switched off of

the Formicivora and onto the flock passing overhead, when I heard the

initial short, variable, greenlet-like songs, which would have struck me as

unfamiliar. After recording several of

those, there was the quick, but obvious break in the recording, without an

annotation, which suggests that after taping several of the mystery voices, I

tried playback, which resulted in an aggressive and persistent bout of amped-up

songs from the male Granatellus, and those continued to the end of the

tape. I seem to remember having a pair

of Granatellus there, but can’t say for certain. But if the recordist that Nacho quoted is

correct, and that females of paraensis often give the short song, but

that males never do, then I probably recorded spontaneous songs of the female

of the pair, and when I played those back, it elicited the more typical

sounding pelzelni-like songs from the male. All of which means nothing, other than

calling into question Boesman’s (2016) assertion of striking differences in

song between the two taxa. Now, if no

such female song exists in nominate pelzelni (and I certainly can’t

remember ever having heard or taped this song anywhere else), then that does

suggest that there are some vocal differences.

But the fact that the male songs are so similar, at least in my limited

sample, does suggest that we simply don’t know enough about this particular

situation to justify a split.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“NO. Too many unknowns, potential confusions in the analysis of song

differences, not a good understanding of the contact zone.”

Comments

from Luciano Naka (voting for Jaramillo): “NO. In my view, the evidence provided above

remains insufficient to give species status to the two forms of Amazonian Granatellus.

Personally, I don’t think that genetic distance alone is a good metric for

speciation. It rather indicates lack of current gene flow and therefore a

potential road towards speciation. In this case, in order to see if the

speciation process has been “completed enough”, I would like to see a good map

with more specimens and genomic data from the potential area of contact, first

to understand if i) the Tocantins is the actual current biogeographical

barrier, and ii) if there is any evidence of current gene flow across the

region. I found the topic raised by Nacho most interesting, in that males and

females may have different voices, and should not be compared. Given these

uncertainties, I see a NO vote as an incentive for someone to do a detailed

assessment of this case, obtaining more recordings, specimens, and sequences

from this interesting biogeographic region.”