Proposal (1020) to South

American Classification Committee

Treat Pionus

seniloides as a separate species from P. tumultuosus

Note: This is a

high-priority issue for WGAC. We don’t

normally do proposals on data-deficient issues.

Background: Our SACC note on this is as follows:

33. The subspecies seniloides was formerly (e.g.,

Peters 1937, Meyer de Schauensee 1970) considered

a separate species ("White-capped Parrot") from Pionus tumultuosus

(“Plum-crowned Parrot”), but see O'Neill & Parker (1977), who noted

that the only differences between the two are the degree of saturation of rosy

pigment; this treatment was followed by Collar (1997) and Dickinson (2003), but

not by Forshaw (1989), Fjeldså & Krabbe (1990), or Ridgely et al. (2001).

There is no evidence of intergradation between the two. SACC proposal to treat seniloides

as a species did not pass.

Recent genetic data (Ribas et al. 2007, Smith et al. 2024) indicate that the

genetic distance between them is about the same as other taxa ranked as species

in Pionus. Del Hoyo & Collar (2014) treated seniloides as a separate species. English

name "Speckle-faced Parrot" for composite species follows suggestion

by Fjeldså & Krabbe (1990).

Here

is the original SACC proposal, from 19 years and 844 proposals ago, which was

rejected 3-6 (Schulenberg did not vote):

Proposal

(176) to South American Classification

Committee

Split

Pionus seniloides from Pionus tumultuosus

Background. These two taxa were treated as distinct

species by Peters (1937). Given that Peterson generally lumped on a massive

scale, this is surprising. O'Neill & Parker (1977) noted that the two taxa

appeared to differ only in degree of saturation of the reddish pigment, a

typical mode of differentiation among New World parrots. However, they did not

formally propose to lump the two taxa.

This step was taken by

Collar (1997:463), who stated: "Race seniloides often regarded as a

separate species, but differences between them slight and superficial,

appearing more appropriate for subspecific separation." Dickinson (2003:

202) also lumped them, citing only O'Neill & Parker (1977) in footnote 4.

On the other hand, Forshaw

(1978:524-25) and Fjeldså & Krabbe (1990:214-215) kept the two taxa as

distinct species, the latter authors stating: "A more detailed mapping of

distribution and variation n[orth] of the Carpish Mtns. is needed in order to

state whether this taxon intergrades with the White-capped P[arrot], and should

in fact include it as ssp." Ridgley & Greenfield (2001: 288-89) also

kept P. seniloides as a distinct species, although they stated that

if intergradation between the two taxa occurred in n. Peru, this would justify

lumping them.

The fact remains that there

are no known intergrades between the two taxa. Furthermore, there is no

gradation within each taxon: that is, it is not the case that birds close to

the range of the other taxon approach the other taxon more in coloring than do

birds at the other end of the taxon's range, as might be expected if we are

dealing with subspecies.

In the circumstances, I

consider that the decision to lump the two taxa was premature and that they are

better retained as distinct species.

I also note that Chrysotis

albifrons Bonaparte, 1845, Atti di Società Italiana di Scienze Naturale

e museo civico de Storia Naturale, Milano, 6, p. 404. (Colombia) is an earlier name applying to P.

seniloides. Salvadori (1891: 330) lists Bonaparte's 1845 name in the

synonymy of Pionus seniloides with (nec Sparrm.). However, Psittacus

albifrons Sparrmann, 1788, the basis of Amazona albifrons, does

not preoccupy Bonaparte's name, either by primary or secondary homonymy. To

preserve stability, it is necessary to declare Chrysotis albifrons Bonaparte,

1845 a Nomen oblitum and Psittacus seniloides Massena &

Souancé,1854 a Nomen protectum under ICZN 23.9.1-2 (1999: 28).

RECOMMENDATION

That Pionus seniloides (Massena

& Souancé,1854) and Pionus tumultuosus (Tschudi, 1844) be treated as

distinct species.

REFERENCES:

Collar, N. J. (1997), Family

PSITTACIDAE(Parrots), Pp.280-479 in del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A. & Sargatal,

J. (eds.), Handbook of the Birds of the World, 4, Lynx Edicions,

Barcelona.

Dickinson, E. C. (ed.)

(2003) The Howard and Moore Complete Checklist of the Birds of the

World. Revised and enlarged 3rd edn, Christopher Helm, London.

Fjeldså, J. & Krabbe, N.

(1990) Birds of the High Andes. Zoological Museum, University of

Copenhagen, Copenhagen.

Forshaw, J. (1978), Parrots

of the World, 2nd edn., Lansdowne Press, Melbourne.

O'Neill, J. P. & Parker,

T. A. III (1977), Taxonomy and range of Pionus seniloides in

Peru. Condor 79, (2), 274.

Ridgley, R. S. &

Greenfield, P. J. (2001) The Birds of Ecuador: Status, Distribution and

Taxonomy. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, N. Y.

Salvadori, T. (1891) Catalogue

of the Birds in the British Museum, vol. 20, Psittaci, Trustees of the

British Museum (Natural History), London.

John

Penhallurick, May 2005

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Comments from Zimmer: "YES. Although

the morphological differences between these taxa are not particularly

impressive, the absence of any real evidence of intergradation, combined with

an absence of any published analysis to support the lump is enough to sway me,

at least until such time as evidence to the contrary is published."

Comments from Robbins: "NO. Given that our

current treatment has seniloides as a subspecies, and we have no

new information, I vote "no" until the time comes that we have

information that can guide us into making a more informed decision."

Comments from Stotz: "NO. Whether seniloides

and tumultuous should be lumped or split is an open question.

However, this proposal makes several comments that are erroneous in making it

seem like this is a recent change. It says "However, they [O'Neill and

Parker 1977] did not formally propose to lump the two taxa." In fact, they

did formally suggest that the two taxa be lumped, saying 'We believe, in the

absence of evidence to the contrary, that the two forms of Pionus under

discussion do not differ enough morphologically or ecologically to warrant

being retained as separate species.' It can't get much clearer than that. This

treatment was adopted by Hilty and Brown in 1986, so it didn't have to wait for

Collar to be adopted. I doubt that Forshaw 1978 had seen the 1977 paper, but I

don't have it in order to check.

"In terms of the lack

of intergradation, I would just note that there is a gap of 150 km between the

northernmost tumultuosus and the southernmost seniloides, so the

lack of known intergrades does not in itself suggest anything to me. I have to

agree with Mark on this one. In the absence of new information, I don't see a

good argument for upsetting our status quo."

Comments from Silva: "NO. We need more

information about the putative contact zone between these two taxa."

Comments from Jaramillo: "NO - In the absence

of a new analysis, keep them as they are. Although my hunch tells me that there

are two species here, the lack of information from the intervening zone is a

key missing piece of data."

Comments from Nores: "YES. Aunque las diferencias en plumaje no son tan

grandes, son aparentemente suficientes como para separarlos. La única contra

que yo veo es lo sugerido por Ridgely y Greenfield de que hubo intergradación

en el N de Perú. Si fuera así, habría que juntarlas.”

Here’s

the basic set up. These are two Andean

cloud-forest taxa that are broadly parapatric with the break not at the N.

Peruvian Low/Marañon as usual but rather somewhere in central Peru. Seniloides occurs from nw. Venezuela

and Colombia S through Ecuador to central Peru in dpto. La Libertad, and then tumultuosus

takes over from dpto. Huánuco south through Peru to central Bolivia in dpto.

Santa Cruz. Although usually presented

as abutting in ranges, in fact there is a substantial gap of roughly 150 km <fact check>

between the southernmost record of seniloides and in La Libertad and the

northernmost record of tumultuosus in Huánuco that is perhaps the

largest true sampling gap in Andean cloud-forest birds, at least in Peru – that

gap is completely unexplored, ornithologically, and there are no known barriers

to dispersal in that gap, i.e. as far as we know continuous humid forest. Thus, technically, that gap should appear in

range maps of every Andean forest bird, but I think it’s fair to assume that if

a species occurs on both sides of the gap, the gap is a sampling artifact.

Whether

there is an actual contact zone or a real gap is technically unknown. However, it seems highly improbable that the

only area these widespread Andean Pionus would find unsuitable from Venezuela

to Bolivia just so happens to coincide with the unsampled gap in central Peru. Further, these canopy-dwelling highly volant

taxa would be among the least likely Andean birds to be thwarted by a forested

gap. Keep in mind there is no known

phenotypic variation in this complex across the biggest barrier to dispersal of

Andean forest birds: the NPL/Marañon. I

predict that there is a contact zone in there that will reveal how these two

interact. The SACC note covers most of

the history of their taxonomy.

Here

are some photos from Macaulay Library (top or left seniloides by

Francesco Verenesi from Napo, EC, and bottom or left by Michael Buckham from

Cuzco):

Here

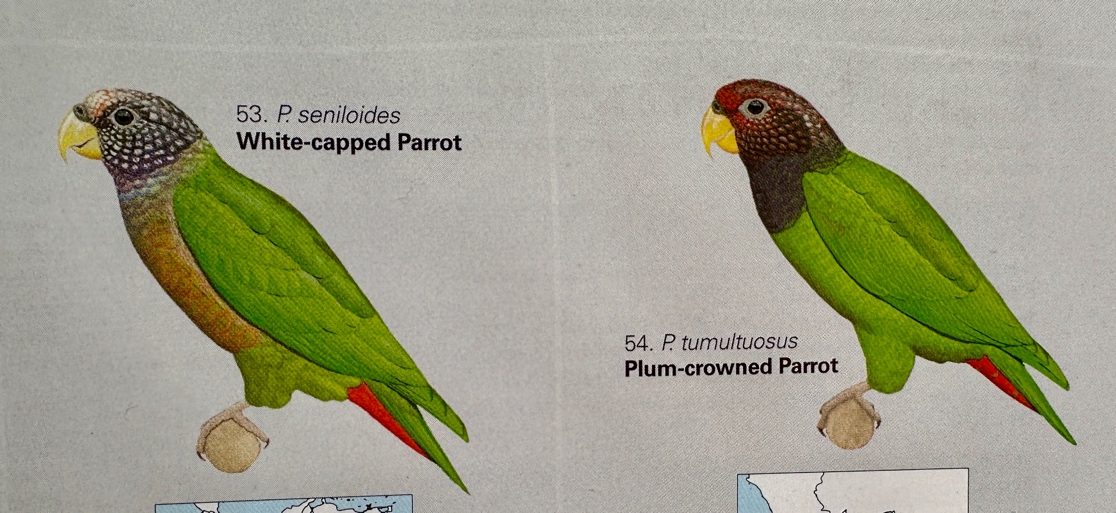

are two plates by F. Jutglar, the one on the left from HBW and the one on the

right in Del Hoyo & Collar (2014):

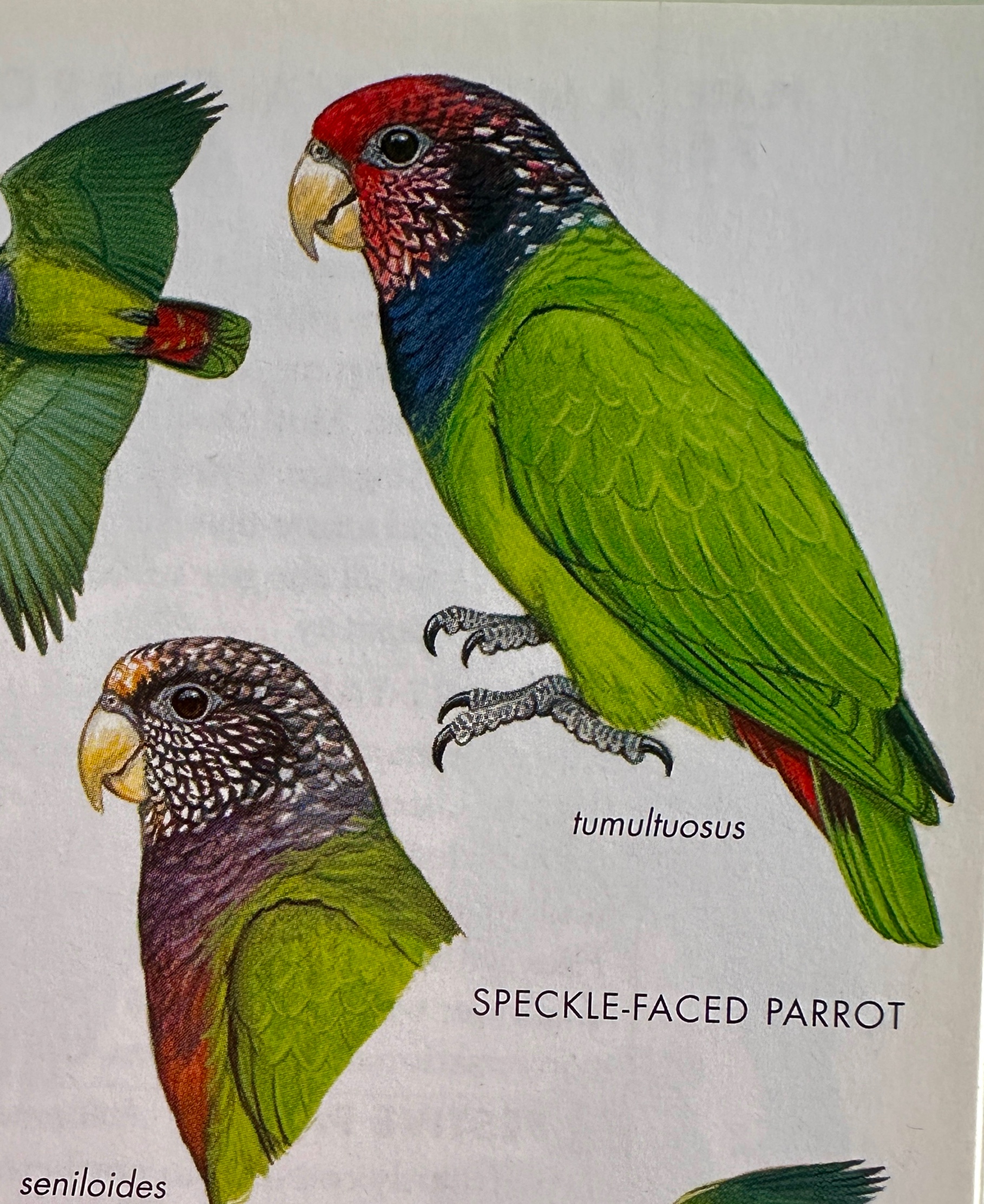

Here

is the plate by Hilary Burn from Schulenberg et al. (2007, Birds of Peru):

Here

are some photos of LSUMZ specimens from Peru.

First our northernmost (n. Ecuador) and southernmost (Cochabamba) specimens:

At

this point, all I want you to note is that the differences between them shown

in the plates are somewhat exaggerated, especially with respect to color intensity. Some of this is likely due to multiple

reproductions of reproductions of the plates, not the artists themselves (for

whom I have the utmost respect for their talents and the challenges in

representing a species in one illustration, particularly when in many cases the

species is unfamiliar to them in life).

Also, at this point one can see why if one were shown only the dorsal

views of the two, one would wonder why anyone would consider them conspecific,

but much less so from the lateral view.

These are the two specimens in our LSUMZ synoptic series, likely chosen

because they represent the extremes in difference between the two taxa: our

northernmost specimen is our whitest, and our Cochabamba specimen is our reddest. That the extremes in color are also the

extremes in geographic representation may just be coincidence, and needs to be

looked at with a larger series.

To

illustrate variation in underparts, here’s the LSUMZ series of seniloides. I don’t have time to sort this out by age,

sex, or molt condition vs. individual variation – the point is only that there

IS substantial variation that needs to be sorted out eventually:

Next,

here are the LSUMZ series of both to show crown color.

1. seniloides, from L to

R: two from La Libertad, then 5 from San Martín and Amazonas, and the in the

separate photo, three from Cajamarca.

Note the variation in extent of white, and if you zoom in, erratic areas

of rose color:

2. tumultuosus, L to R: 1 from

Cochabamba, 2 from Puno, 1 from Junín, 3 from Huánuco. Not as much variation as in seniloides, but

note that the darkest one is the once from Cochabamba and the palest is one of

the three from Huánuco. Somewhat suspicious,

and at least worthy of further investigation, at least if a larger N could be

assembled:

Concerning

the red in the crowns of some seniloides, here are close-ups of the two

with the most red:

Note

that the distribution of reddish color is irregular. This may just be individual or age variation,

analogous to the variation in red feathering in the face of some other New

World parrots, but a hypothesis that that it represents gene flow, past or

present, from southern tumultuosus is worth considering. The instinct of a previous generation of

ornithologists, who typically based their taxonomic conclusions primarily on

phenotype distribution in geographic arrangements of specimens like this, would

be to label this variability as “character instability”, something often

associated with zones of introgression. However,

I didn’t have to go any further than Restall et al. (2006) to see that this

variation occurs in the northern Andes as well:

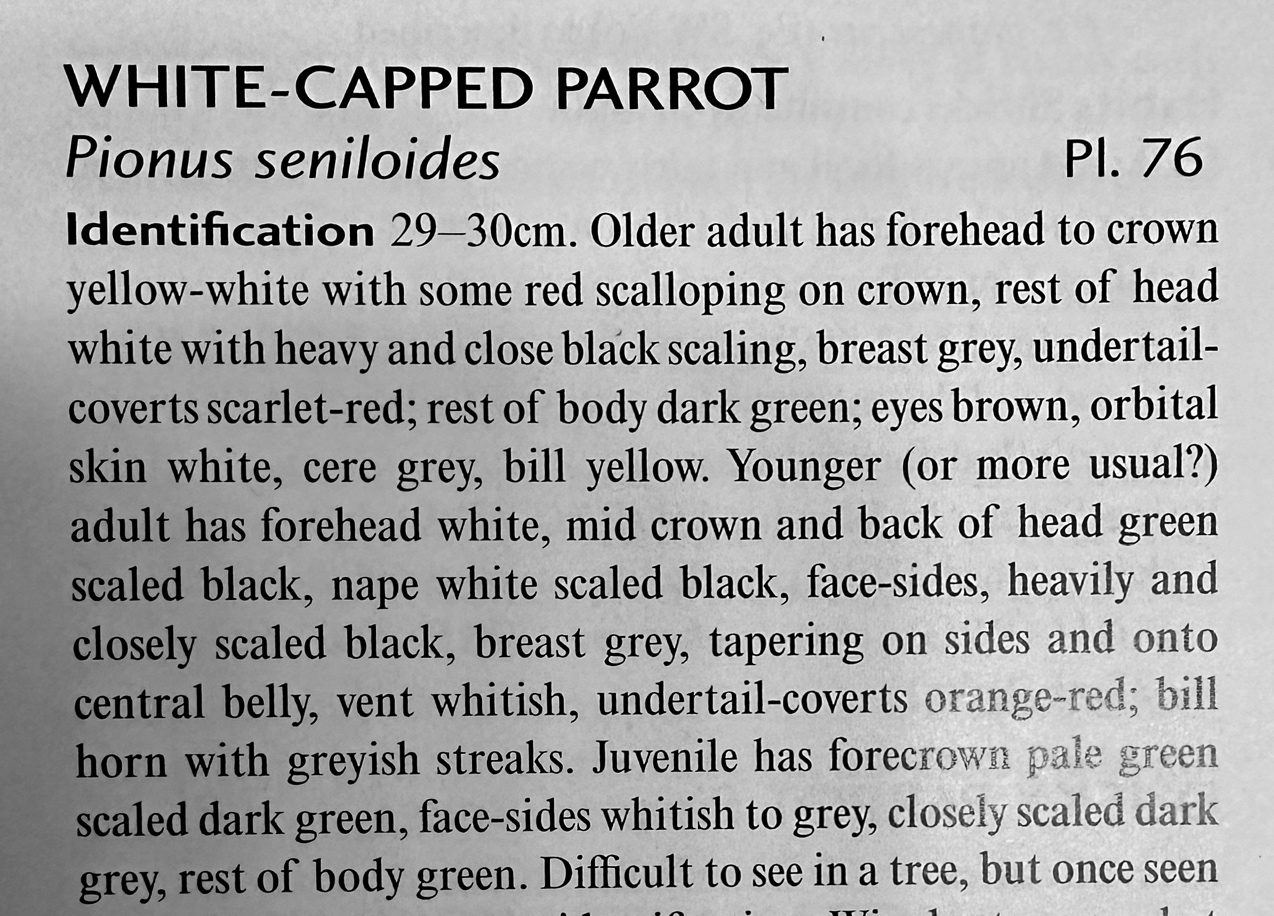

Although

the basis for determining older vs. younger adults was not given, this

minimally establishes that the occasional red feathering is not concentrated

near the potential contact zone and is unlikely to be due to ongoing gene flow.

Here

is the crown of another specimen of tumultuosus that might have caught your eye

in the photos above, one from Cajamarca:

My

first reaction was naturally that this was going to be what younger individuals

looked like in terms of crown color.

However, the specimen label reads, “left testis 8x5 mm; no bursa”, so

there is no internal sign of this being a young bird. Note also that it has an above average amount

of red in the forecrown. I’m not sure

what my point is here is except to point out additional variation

The

first to propose that seniloides and tumultuosus were conspecific

were O’Neill & Parker (1977), who were reporting some of the first records

of both taxa from Peru. They had few

specimens of either to examine. This

species is not common in collections – collecting canopy parrots in Andean

cloud-forest is not easy. Here is their

rationale:

“After

careful scrutiny of the specimens available to us we have come to the

conclusion that the only difference between P. seniloides and P.

tumultuosus is the amount of rose or plum color present in the plumage of

the head and belly. The northern birds, “P. seniloides,” have only a

wash of this color present on their otherwise whitish head plumage and have the

belly with a variable amount of rosy color, but the southern birds. “P.

tumultuosus.” have the head strongly marked with this color and have solid green

bellies. The older birds of either form apparently have the greatest saturation

of the rosy coloration in their plumage.”

And

“We

believe, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, that the two forms of Pionus

under discussion do not differ enough morphologically or ecologically to

warrant their being retained as separate species.”

Some

but by no means all subsequent classifications treated them as

conspecific. Schulenberg et al. (2007;

O’Neill and Parker were co-authors, the latter posthumously) maintained then as

conspecific. No differences in vocalizations

were mentioned.

New

information:

Del

Hoyo & Collar (2014) treated seniloides as a separate species based

on the Tobias et al. point scheme as follows:

earlier

information:

“Often treated as a distinct species, but

united with P. tumultuosus (e.g. in HBW) following

“(1). Here reseparated on account of its

white forehead and grey-scaled white crown vs all plum-red crown (3); white and

grey vs plum-red, white and blackish flecks on face, ear-coverts, chin and

throat (2); brownish-grey extending down breast to belly on typical birds vs

shading rapidly to green on mid-breast (2). Monotypic.”

There’s

not really any new information here, just plugging known plumage characters

into a controversial methodology. Note

that the threshold of 7 points achieved solely on the basis of plumage

characters. Pionus and many other

parrot genera have complex, gaudy plumages, so the chances of any taxa reaching

the threshold of 7 are obviously much greater than in other groups of birds

with more conservative plumage evolution, including other genera of parrots. This is one of the fundamental conceptual

flaws in the Tobias et al. scheme, i.e. no consideration of phylogenetic biases

in plumage variation.

As

a reminder, the Tobias et al scheme is based on scoring 58 pairs of parapatric

bird taxa for which fundamental details of their interactions. However, of those 58, 55 (95%) are

passerines, and these are almost all either temperate latitude passerines or

thamnophilids, i.e. even within passerines, the foundation of the system is

highly non-random. How many pairs of

parrot taxa went into the Tobias scheme on which this split is based? ZERO.

For a full critique of using the Tobias et al. scheme for changes in

taxonomic rank, see my two reviews (Remsen 2015, 2016).

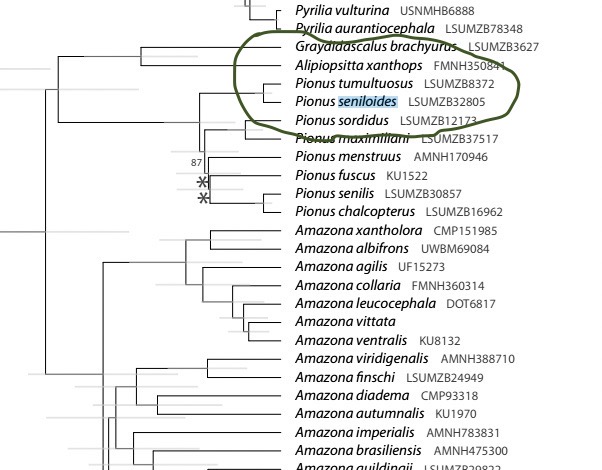

The only truly new data are the genomic data of

Ribas et al. (2007) and Smith et al. (2024), which confirm that they are sister

taxa and show that they differ genetically, neither of which is of course a

surprise to anyone. Here is a screen

shot of the relevant part of the tree from Smith et al. (2024). The degree of differences is toward the low

end of that shown by taxa traditionally treated as separate species, but

without deeper sampling at the subspecies level, there are insufficient data

for a comparative analysis, and in in my opinion the genetic data are

inconclusive. Here is the relevant

portion of the Smith et al. tree:

Discussion

and Recommendation:

This

is another difficult situation to assess.

Reasons

to vote YES for the split could be: (1) Those differences in head and breast

color are substantial, arguably at the subjective limits of variation

traditionally relegated to subspecies rank, and presumably are quite striking

to these highly social birds. (2) There is no sign of consistent geographic

variation over the large ranges of the two taxa, and thus if there is a hybrid

zone between the two, it must be entirely within the unsampled gap, without any

known signs of gene flow at their nearest sampling points.. (1+2+3) Therefore,

burden of proof rests on treatment as conspecific, especially since the paper

that proposed treating them as conspecific was not quantitative.

Reasons

to vote NO could be: (1) Taxa treated as separate species usually have

differences in flight calls. One

exception to this is Pionites melanocephalus/P. leucogaster , but that

is also a controversial case in terms of species limits. (2) Are there really

enough specimens and have they been examined sufficiently thoroughly to really

be sure there is no gene flow?

Certainly, this level of study of geographic in phenotypic would be

required for a modern study. (3) Eventually, the sampling gap is going to be

filled, so what’s the rush in pushing a change at this point before we have a

chance to get a solid answer on what’s going on at contact?

I’m

going to vote NO on this one, but without strong conviction. To be convinced to split them, I’d like to

see a synthesis of comparisons of similar cases in parrot genera in terms of

what are traditionally treated as sufficient differences in plumage data for

treatment as separate species. Better

yet, a synthesis of “knowns”, i.e. what’s known about plumage differences and

contact zones in parapatric parrot taxa treated as species and subspecies. Unfortunately, I think the number of

well-studied cases in parrots is too few to provide much guidance. Another approach would be to synthesize the

degree of plumage differences in sympatric congeners in parrots, i.e. cases in

which the taxonomy is indisputable – are the differences here similar to those

shown by sympatric congeners? None of

these approaches would be very satisfying, but at least they would provide a slightly

better foundation for a temporary solution until the contact zone is studied.

English

names:

The pre-lump names for the two were White-capped Parrot and Plum-crowned

Parrot, both good names, so that’s what our SACC names would be unless someone

wants to do a proposal.

References: (see SACC

Bibliography

for standard references)

O'NEILL, J. P., AND T. A. PARKER III.

1977. Taxonomy and range of Pionus "seniloides"

in Peru. Condor 79: 274.

Van Remsen, July 2024

Vote tracking chart:

https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart968-1043.htm

Comments

from Areta: “NO. I vote to follow

O´Neill & Parker in considering seniloides

and tumultuosus as

part of a single species. I would like to see better DNA evidence and at least

a vocal analysis and a careful analysis of plumage variation across geography.

These analyses could provide support one way or the other, but without them, I

prefer to follow those who have dedicated more field effort. (i.e., no split).

Van´s sample of specimens made me raise my eyebrows, even when anyone who had

looked carefully enough at Pionus

knows about the sheer amount of variation that they exhibit. Learning about how

the parrots behave in their contact zone will be key. Meanwhile, the large

amount of variation coupled to a reduced degree of genetic differentiation call

for caution.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“NO for now (again). The decisive data for resolving this one will have to come

from specimens with associated vocal and genetic information, collected in that

150 km “contact”(?) zone.”

Comments

from Del-Rio:

“NO. After studying pigmentation more closely, I am

starting to believe these changes in carotenoid based pigments are highly

plastic and dependent on food availability. I also think the putative contact

zones should be better sampled.”

Comments

from Lane:

“NO. For now, I would stay with the decision made by O’Neill and Parker (1977).

Until we have a better understanding of what’s going on in central Peru, it

seems ill-advised to jump to conclusions in the absence of evidence.”

Comments

from Robbins:

“More information is needed, as pointed out in the

proposal and by Nacho, thus for now I vote NO.”

Comments

from Claramunt:

“YES. I vote to revert to the two-species scheme. A “belief” that two taxa do

not “differ enough” is not acceptable evidence of conspecificity. There is no

evidence of intergradation despite potential contact. Even if they were

allopatric, what is the logic, under the biological species concept, of lumping

to taxa that differ so much in a trait that with obvious potential influence in

species recognition and sexual selection? Most parrot species that differ that

much in their head and face color are treated as different species.”

Additional

comments from Stiles:

“Santiago´s point that the two taxa are as different in plumages as are several

other pairs of species in Pionus is well taken, but in at least

some such cases, differences in ecology, voice and/or genetics also occur. The

plumage differences could be the result of only 1 or 2 mutational differences

in the synthesis and deposition of red pigments. Here, genetic data are

insufficient for a clear verdict and no good vocal information appears to

exist. Are the plumage differences sufficient to conclude that were they to

come into contact, they would not interbreed – or conversely, be genetically

compatible enough that gene exchange could occur? We don’t know, and won’t know

enough to answer these questions until we have specimens (and, hopefully,

recordings) from that frustrating 150 km gap. Until then, the current consensus

considers these taxa as subspecies, and the only advantage to calling them

species (with an equal lack of evidence) would be better to call attention to

and maintain more interest in this problem. If only for this rather quixotic

reason, I could be persuaded to vote Yes to the split.”

Additional

comments from Remsen:

“I think Santiago is probably correct on this, but I just can’t bring myself to

switch to a Yes vote on this until we have more data, either on the sampling

gap or flight call differences. I’m

always queasy about using plumage variation in parrots as markers for species

limits given how much individual variation exists, as in this case.”