Proposal (1023) to South

American Classification Committee

Recognize

Trichothraupis griseonota as a

separate species from T. melanops

Our

current SACC note reads:

"14f. The Andean population of Trichothraupis

melanops was described as a new species, Trichothraupis griseonota,

by Cavarzere et al. (2024). SACC proposal badly needed."

Cavarzere

et al. (2024) described the Andean-foothill populations of T. melanops as a new taxon at the species level under the name T. griseonota, following the PSC (but

arguing that the same interpretation would be possible under the BSC). They

based their conclusions on the examination (and measurement) of 314 specimens from the Atlantic Forest population, and 52

from the Andean-foothill population. They also examined 520 sound recordings of

the Atlantic Forest population, and 19 from the Andean-foothill population.

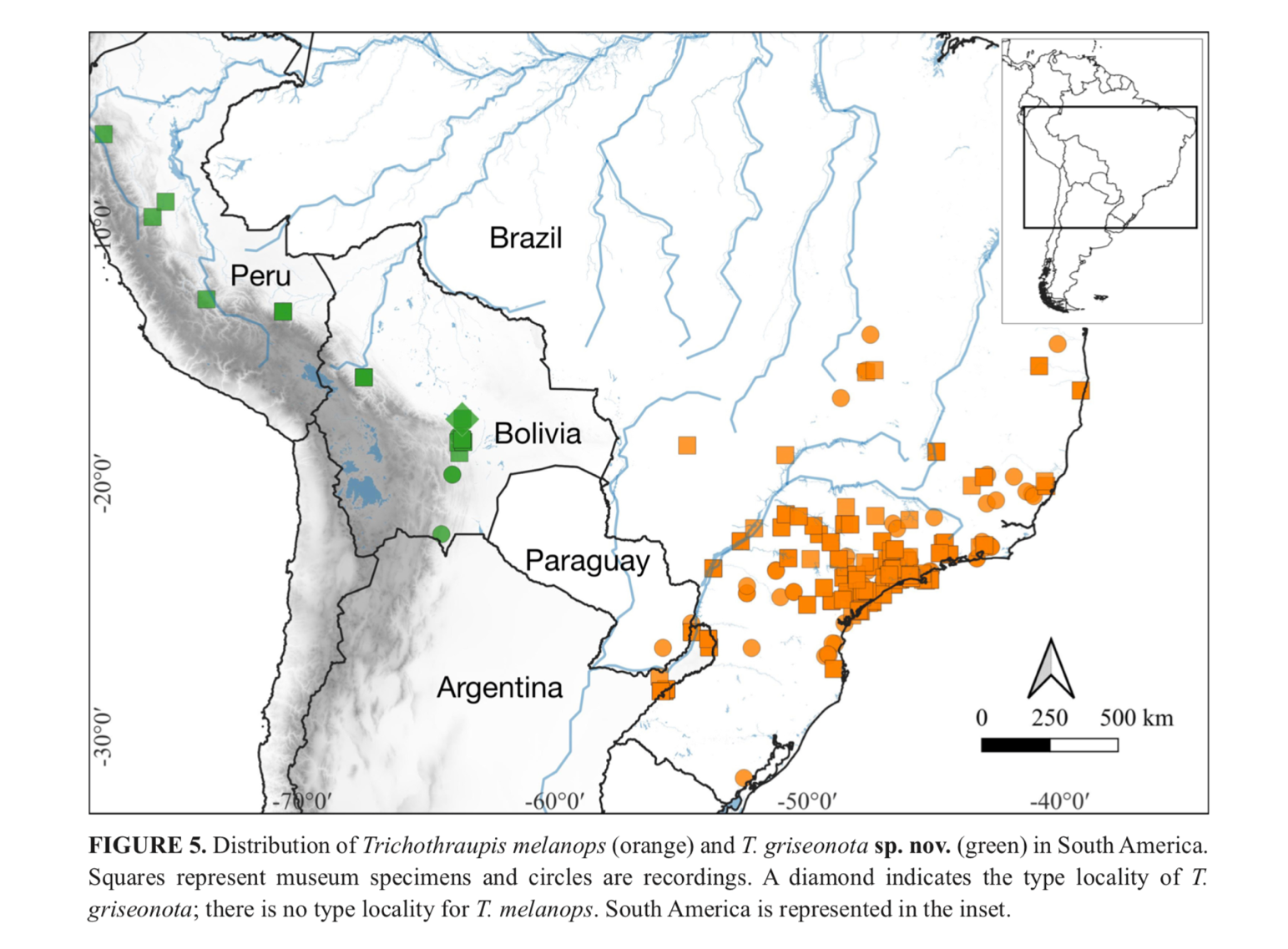

The current distribution of both taxa is more extensive than shown

in their specimen map (Figure 5, below; e.g., there are overlooked documented

photographic, sound, and published specimen records in NW Argentina,

photographic records in the tall, riverine forests in eastern Formosa in NE

Argentina, and numerous records along the Paraguay river).

Earlier,

Zimmer (1947; note number 51, and not 52 as cited in Cavarzere et al.) referred

to geographic variation in Trichothraupis

stating that

"There is a slight possibility that distinctions might

be found in Peruvian specimens as compared with Paraguayan and Brazilian

material, but the range of variation in the species is so great (126 specimens

examined) that little is to be expected. Two adult males from Bolivia (Province

of Sara) have a greater posterior extension of the black area on the sides of

the face than any other males at hand from any locality, but there is

considerable variation within this extreme limit. These two males also have the

longer upper tail-coverts decidedly blackish, with narrow olive tips, but this

character is present in a small number of Brazilian and Argentine birds, also,

and is of doubtful taxonomic value.”

Prior

to this, Hellmayr (1936) stated in a footnote:

"The

supposed distinction of a northern form (auricapilla),

which we at one time advocated, has not been corroborated by additional

material since. Birds from Espirito Santo and Rio de Janeiro seem to be

precisely like others taken in southern Brazil and Paraguay. Bolivian and

Peruvian specimens merely differ by very slightly paler under parts, but the

divergency appears to me too insignificant to justify its recognition in

nomenclature, although there is obviously a wide gap between the eastern and

the Andean ranges of the species."

Therefore

both, Zimmer and Hellmayr discussed slight plumage variation in T. melanops.

The holotype of griseonota

is "MACN 8979a, Male. BOLIVIA, Buenavista, Santa Cruz, 30 July 1916, J.

Steinbach leg., 450 m". So, how is it possible that the holotype is

not shown in the paper itself or in the supplementary material? It is not too much

asking to show photographs of a holotype in the 21st century!

Cavarzere et al. (2024) provide the

following diagnosis:

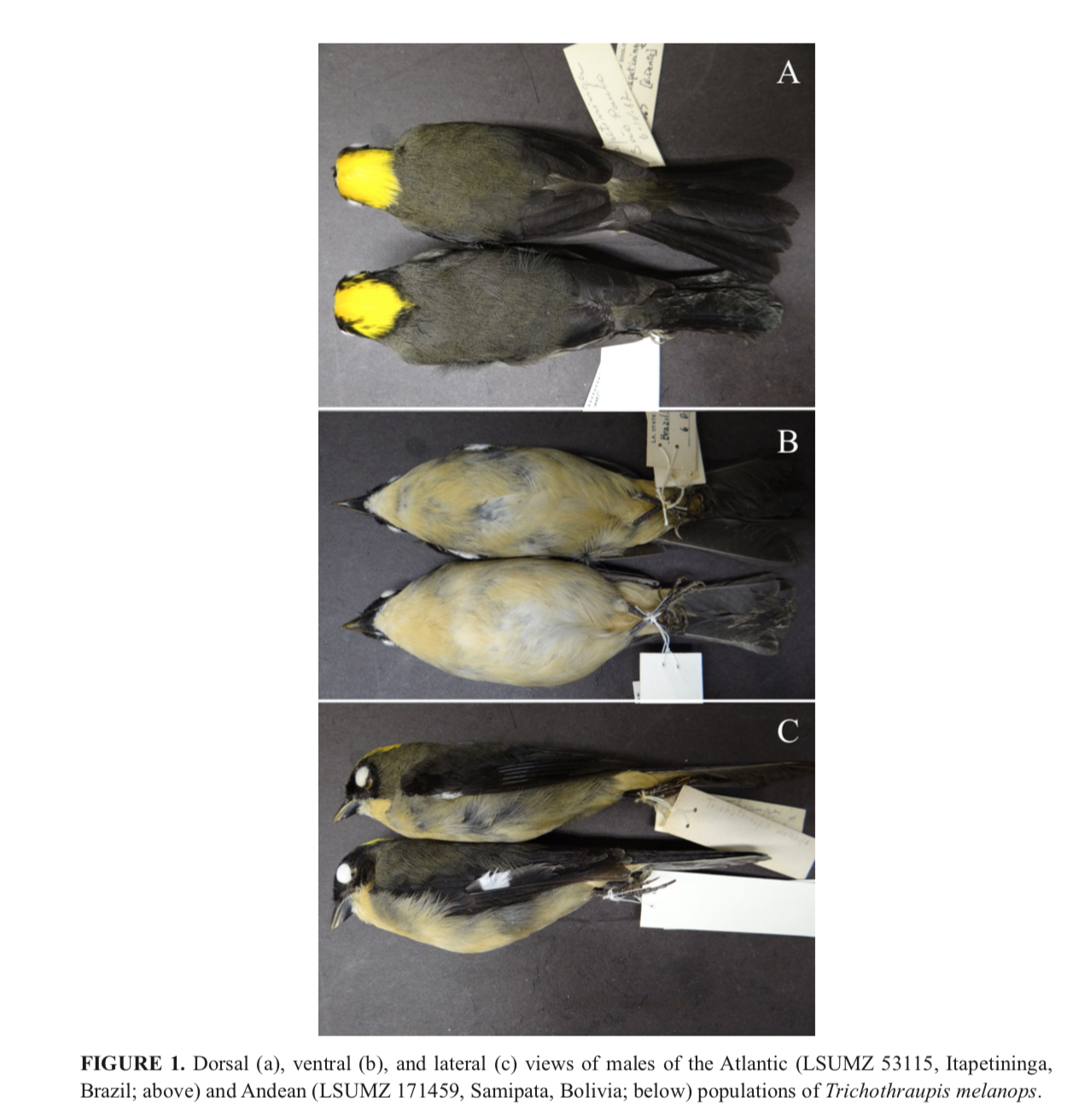

"Diagnosis. Four fixed plumage traits and one

morphometric trait diagnose Trichothraupis griseonota from its sister

species, T. melanops. The first and most noteworthy is the black facial

mask. In the new species, it includes the auricular region (Fig. 1; Fig. S3),

whereas in T. melanops this mask is only a narrow line behind the eye,

not reaching the auriculars. In a few Atlantic specimens (AMNH 774505, LSUMZ

59405, MZUSP 27851) there is some black in the auriculars, but in those cases,

it is mixed with green, producing a mottled appearance, unlike the homogeneous

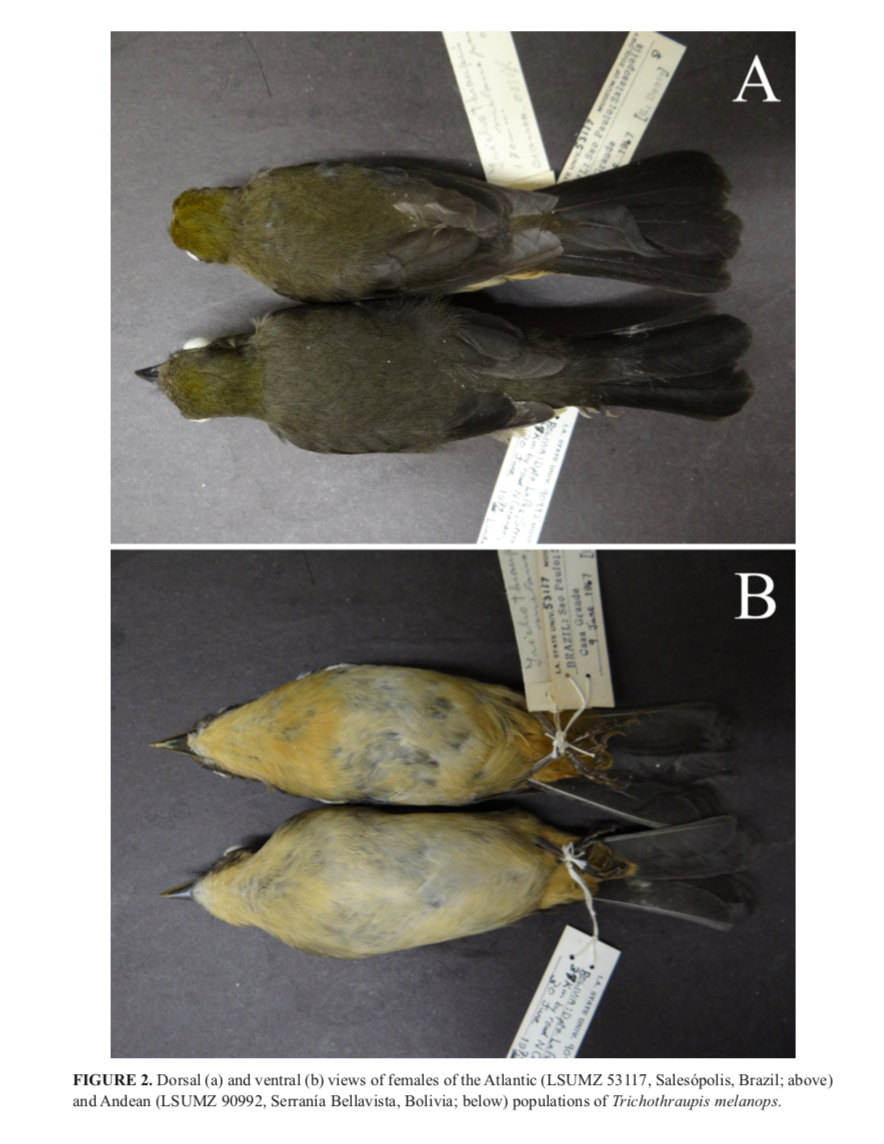

black in T. griseonota. A second diagnostic character is the paler

underparts of adult males and females. This is especially evident in the

undertail coverts, which are a cream color to buff-yellow in T. griseonota,

versus cinnamon in T. melanops, and in the chest, in which both species

have a more orange tone than in the belly, but less distinctly so in the new

species, where the color of the chest is more buff-yellow, versus buff in T.

melanops (Fig. 1). Adult females of T. griseonota are also somewhat

paler in the underparts than in T. melanops, but the difference is not

as pronounced as in males, and sexual dimorphism of plumage color in the

underparts is more evident in T. griseonota than in T. melanops.

The third plumage characteristic is the color of the back of adult males, which

is greyer in T. griseonota, versus being more greenish-olive in T.

melanops (Fig. 1; Fig. S3). The last character in which the two species

differ is the breast coloration of females, which is subtly but consistently

darker in Atlantic populations (Fig. 2). Trichothraupis griseonota also

has significantly shorter tarsi compared to T. melanops (Fig. 4)."

Looking at these photographs we see

minimal plumage differences showing very slight differences in dorsal

coloration, even more subtle differences in ventral coloration, and a

noticeable (yet variable) difference in the amount of black in the goggle.

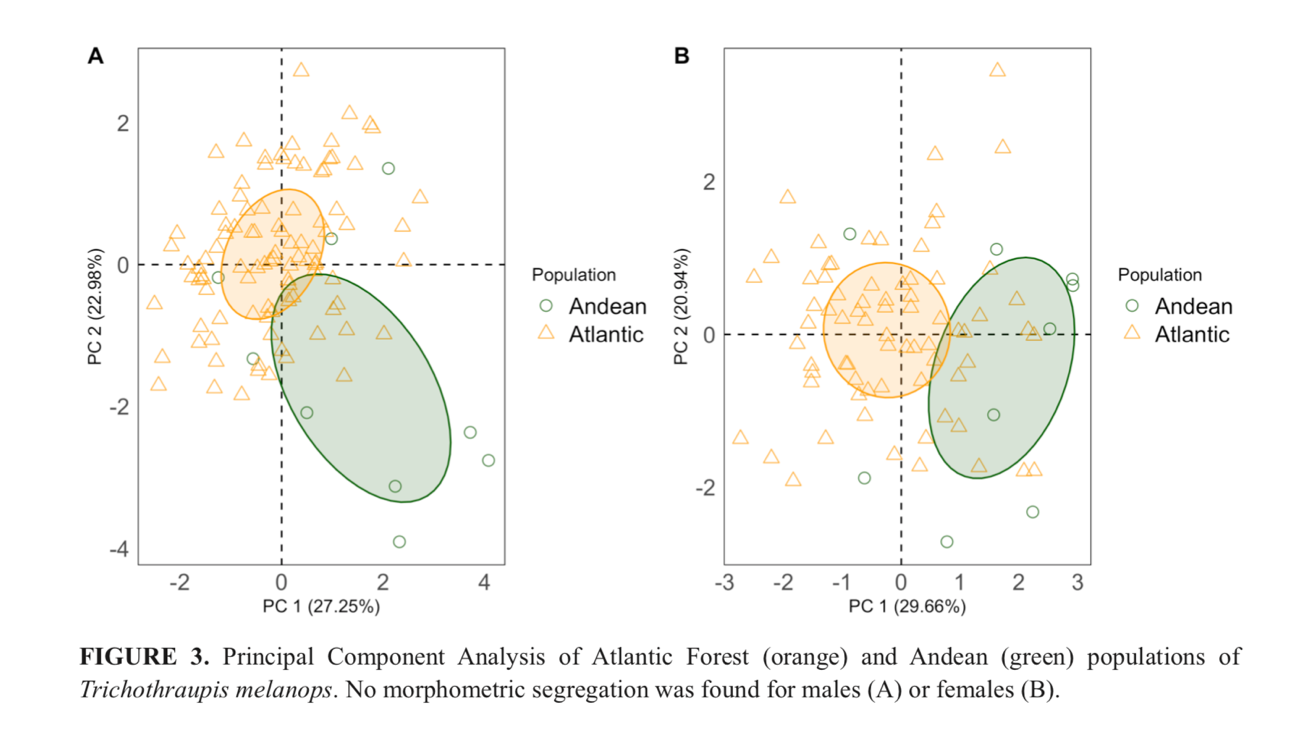

"Morphometrics.

The Andean population has

significantly shorter tarsi, on average, than the Atlantic population, but all

traits show measurement overlap. The mean measurements of both populations are

shown in Table 1. Principal Component Analysis indicates that morphometrics

segregate the two populations, although incompletely (Fig. 3). Within this

context, the two-factor comparison of sex and populations only showed

significant differences for culmen (p<0.010) and wing (p=0.000) measurements

between sexes, while tarsi measurements (p=0.000) were significantly shorter

among Andean populations (Table 1). There were no significant differences in

the interactions between them (Bonferroni post hoc test p>0.02). Therefore,

the Andean population is morphologically distinguished based on plumage color

patterns and tarsus length (Table 2)."

The PCA show wide overlap between the

taxa (i.e., no segregation between taxa when sorted by sex), and univariate

analyses (for which see their Table 1) do not show well-marked differences

(although the authors claim a difference in tarsus length, the effect size for

such a comparison is small). Thus, morphometry show at most subtle differences

between the taxa.

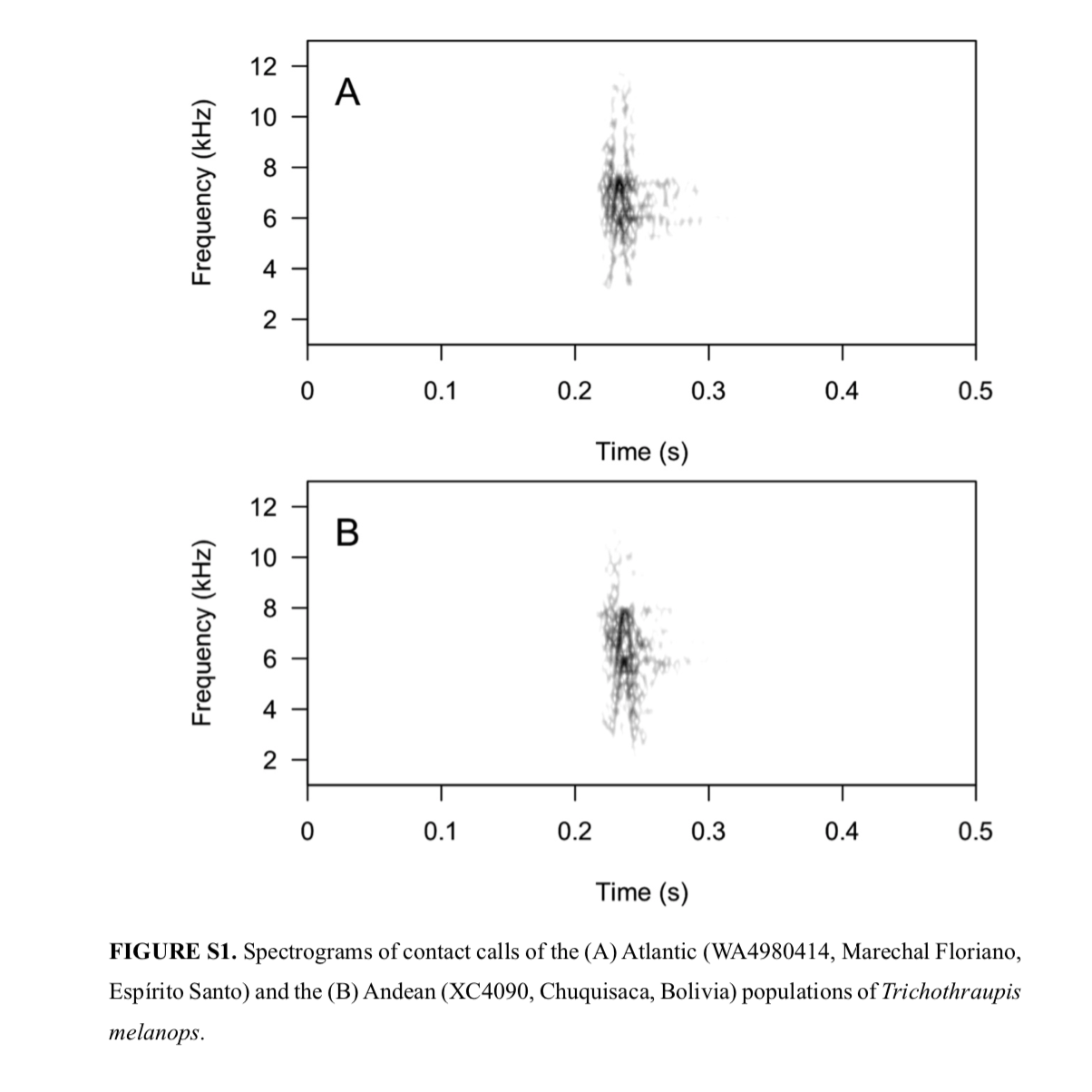

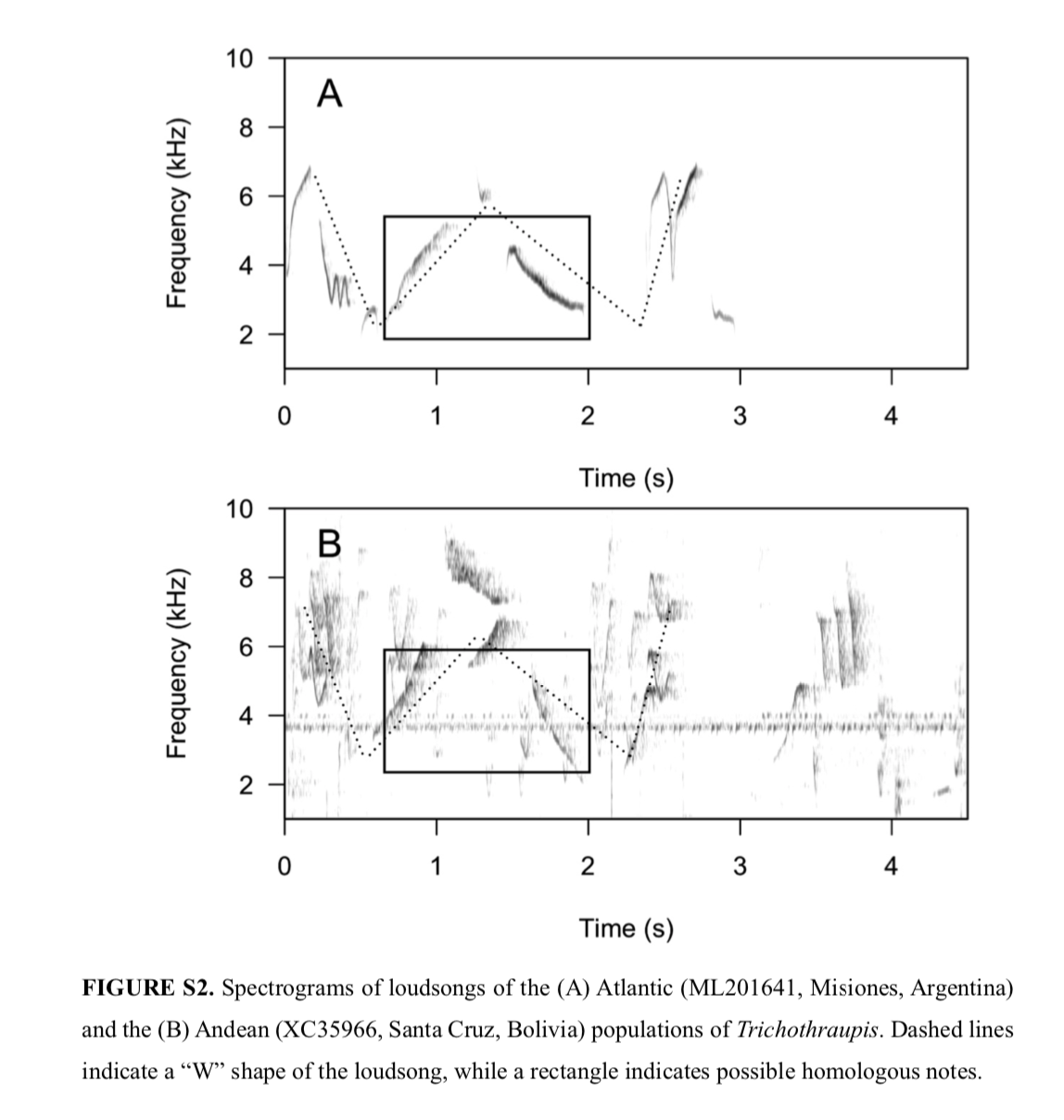

Despite the large number of available recordings, the vocal

analyses included only two recordings of songs of the Andean-foothill

population:

"Vocalizations.

Of the recordings of the

Andean population, only two were loudsongs, and only one consisted of a

reasonable-quality recording to allow for the creation of spectrograms. The

lack of Andean data precluded us from quantitatively analyzing loudsongs.

Qualitative inspections failed to find visual differences between contact calls

(Fig. S1). The Atlantic loudsong is clearly composed of a series of upslurred

and downslurred notes, forming a “W” shape. It seems to share a two-note

homologous pattern with the Andean loudsong, but the number of loudsong

emissions within the recording did not allow for further evaluation (Fig.

S2)."

"Contact calls are visually identical in spectrograms and

sound quite similar for both allopatric populations, but for most passerines,

when sister clades are morphologically and genetically distinct, supposedly

homologous loudsongs also typically differ quantitatively, including for

Neotropical oscine and suboscine species (Isler et al. 1998; Bocalini

& Silveira 2016). Therefore, we also recommend analyzing more loudsongs as

more recordings of T. griseonota are made available. "

The calls of both populations are identical (our own recordings of

both populations from Argentina further reaffirm that), and there was not

enough vocal material to adequately characterize songs (which can be quite

complex in T. melanops, therefore not

an easy task to accomplish).

The genetic data used by Cavarzere et al. (2024) to support their

species-level taxon comes from Trujillo-Arias et al. (2018). Most notably,

their discussion bears on this issue:

"the

divergence between these rainforests in a sample of three birds varied from 1.3

My (Amazona pretrei/A. tucumana, Rocha et al., 2014) to

about 0.72 My and 0.15 My (T. melanops

and Pipraeidea melanonota, this study

and Lavinia, 2016, respectively). However, it should be noted that although the

re-current connections between these biomes could have led to periodic

re-establishment of gene flow between regions after the initial separation, the

historical gene flow between these rainforests has not been high enough to

preclude divergence.

“Finally,

a definitive analysis of the phenotypic variation of T. melanops is

necessary to determine the taxonomic status of its populations. Our results

indicate that the Andean and Atlantic populations of T. melanops are

genetically isolated (i.e., migration between populations M < 1 individuals

per generation), and therefore, its current classification as a monotypic

species might not be adequate to reflect its evolutionary history. "

Of course, these two being allopatric populations, one would not

expect much reciprocal genetic influx. This being said, the genetic

differentiation between the Atlantic Forest and Andean-foothill populations is

very low.

Recommendation: We

recommend a NO vote. The reduced levels of phenotypic and genetic

differentiation coupled with a lack of vocal differences in calls (and unknown,

but apparently trivial levels of vocal differentiation in song; pers. obs.)

indicate to us that griseonota can be

a good, mildly differentiated subspecies of T.

melanops but not a separate species from it.

References

Cavarzere, V., Costa,

T.V.V., Cabanne, G.S., Trujillo-Arias, N., Marcondes, R.S. & L.F. Silveira.

(2024) A new species of tanager (Aves:

Thraupidae) from the Eastern slopes of the Andes. Zootaxa 5468:

541–556.

Hellmayr, C.E. (1936)

Catalogue of birds of the Americas, part IX, Tersinidae, Thraupidae. Field

Museum of Natural History Publications in Zoology 13:1–458.

Trujillo-Arias, N.,

Calderón, L., Santos, F.R., Miyaki, C.Y., Aleixo, A., Witt, C.C., Tubaro, P.L.

& Cabanne, G.S. (2018) Forest corridors between the central Andes and the

southern Atlantic Forest enabled dispersal and peripatric diversification without

niche divergence in a passerine. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution

128: 221–232.

Zimmer, J.T. (1947) Studies

of Peruvian birds. No. 51. The genera Chlorothraupis,

Creurgops, Eucometis, Trichothraupis,

Nemosia, Hemithraupis, and Thlypopsis,

with additional notes on Piranga. American Museum Novitates 1345.

Juan I.

Areta and Mark Pearman, July 2024

Vote tracking chart:

https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart968-1043.htm

Comments

from Remsen:

“NO. The authors did a great job of

quantifying the differences between the two populations, especially the newly

discovered diagnostic plumage traits of the two populations. So, the data strongly justify describing the

Andean population as a new taxon … but not as a

species under the BSC but rather as a subspecies. This designation calls attention to their

separate evolutionary history by formal recognition through taxonomy of this

level of biodiversity. What is needed

now, in my view, is a study to show that these two taxa have diverged to the

point of “no return” in terms of divergence in the comparative framework of

Thraupidae divergence through a formal analysis of song differences. Strictly on the basis of genetic differences

and time-since-separation, the data suggest a better fit with subspecies-level

divergence (although I will spare us my usual diatribe on using genetic

divergence as THE arbiter of species vs. subspecies assignment.”

Comments from Stiles: “NO. To me, the

differences in plumage between griseonota and melanops are

sufficient for recognizing the former as a good subspecies, but fall short of

favoring its status as a separate species, and the N = 1 of its loudsong

likewise makes support for the split less convincing. The genetic information

is also borderline and given the records (including specimens?) from Argentina

and Paraguay that narrow appreciably the gap in distributions of the two, any

such specimens should at least be subjected to genetic analyses.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“NO. As Van and Gary pointed out, overall, the data

support a subspecies, not a species. The plumage differences are subtle and the

morphological data overlapping. Also, according to the phylogenetic analysis of

Trujillo-Arias et al. (2018), the genetic differences are minor, and the two

taxa are not reciprocally monophyletic. I don´t mean that reciprocal monophyly

would be necessary, but it would make a stronger case for species status.

Finally, the contact calls and loudsongs don´t seem very different (although I

am not an expert), and not including data from individuals close to the

potential contact zone is problematic.”

Comments

from Robbins:

“For

the reasons Areta and Pearman state in their proposal, I vote "NO"

for treating griseonota as a species.”

Comments from Del-Rio: “NO. Because of low genetic

differentiation and slight morphological differences,

griseonota should be

treated as a subspecies.”

Comments

from Lane:

“A solid NO here. This taxon, while worthy of a name, is hardly distinctive

enough to warrant splitting from T. melanops by BSC standards. This is

why PSC species are a whole different ball of wax from those that most

taxonomists would recognize as distinct.”

Comments

solicited from Kevin Burns: “Cavarzere et al. (2024) is an exciting and important paper

because it reveals previously unreported differences between Andean and

Atlantic Forest populations of Trichothraupis melanops. It’s both

surprising and fascinating that these differences remained underappreciated

until now. In addition, the genetic study of Trujillo-Arias et al (2018)

provides a nice complement. It is a thorough and rigorous study that includes

phylogenies, population genetic analyses, and tests of demographic models.

After reading both of these papers, I’m left feeling this is a borderline case,

but see below.\

“The model

testing of Trujillo-Arias et al (2018) inferred a scenario of peripatric

divergence, with dispersal from the Atlantic Forest to the Andean Forest. This

is also illustrated in their phylogeny, where there is not reciprocal monophyly

between the two sets of populations. Instead, the Andean populations form a

clade embedded within the Atlantic Forest populations. This is what you would

expect in a case of recent peripatric speciation. The timing of the splitting

event is estimated as 0.728 million years ago (mid-Pleistocene). On the

surface, this seems low compared to other avian species splits. However, I went

back to the data from Burns and Racicot (2009), and I found similar levels of

divergence between sister species. In Burns and Racicot, we looked at phylogeny

and biogeography of subfamily Tachyphoninae (Tachyphonus, Ramphocelus,

Lanio, Eucometis, Trichothraupis, and relatives) using cyt

b. Therefore, our dating is based on similar methods and markers as the

Trujillo-Arias et al. study. Several recognized species splits in Burns and

Racicot are of a similar age or even more recent than the Trichothraupis

split. These include Lanio aurantius and L. leucothorax

(0.594 mya), Ramphocelus carbo and R. melanogaster

(0.515 mya), and Ramphocelus dimidiatus and R. nigrogularis

(0.856 mya). Based on these data, the level of divergence seen between the two

proposed species of Trichothraupis cannot be dismissed outright as “too

low”.

“For the

morphological data, there is quite a bit of overlap in the PCA plots of

Cavarzere et al, but the two proposed species do generally fall out in

different portions of the graphs. The authors also describe a significant

difference in tarsus length, but I’m not sure what to make of this. Overall, I

don’t think the morphology adds much to make the case for a species split.

“For the plumage,

the two forms differ in ventral and dorsal color, which is obvious in the

photographs. I wish we had quantitative (spectrophotometric) data comparing

plumage color of all individuals so we could see any potential overlap or lack

of overlap between the two forms. Also, an examination of the color differences

using an avian visual model might be helpful when thinking about differences

and how they might play out in courtship. Nevertheless, I am more convinced by

the differences in the “goggles” – specifically the extent of melanin on the

face mask. There is clear discrete difference in the facemask, with the Andean

birds having black extending onto the auricular. The authors also note that the

crest/crown has black framing in some of the Andean birds.

“Based on the

genetics and plumage differences, these two forms are easily two species under

the phylogenetic species concept.

“So what about

the biological species concept? Well we need to think more about reproductive

isolating mechanisms and try to predict what they would do if they came into

contact. This is the spatial dimension problem that the BSC consistently faces

for geographically isolated populations. We know that vocalizations are very

important in songbirds for reproductive isolation. The authors note that both

species have similar call notes, so that doesn't provide evidence for a split.

For songs, there aren’t enough recordings of the Andean birds for comparison to

Atlantic forest birds. The fact that the Andean birds apparently sing less

(something also mentioned in the Islers’ tanager book) is intriguing. However,

based on available information, vocalizations aren’t helpful in arguing these

are two biological species.

“Since the

genetics shows enough time to evolve reproductive isolation (as seen in related

sister pairs) and the morphology and vocalization data are inconclusive, I

think it comes down to the significance of those plumage differences. For a Yes

vote on biological species, I think you would have to argue that the plumage

difference are important in courtship. For a No vote on biological species, I

think you would have to argue that those differences are inconsequential for

courtship. I don’t think there is much, if anything, known about Trichothraupis

courtship, but personally I haven’t been able to observe them much in the

field. Overall, the differences in plumage seem slight compared to that seen in

other sister pairs in this subfamily. Therefore, if I were asked to vote on

this, I would probably vote No on biological species status for these two

proposed species, although they would qualify under other species definitions.

“Regardless of

species status, I think the Cavarzere et al. (2024) paper is an important one

for understanding diversification and also demonstrates what discoveries await

in museum collections!

Burns, K.J. and Racicot, R.A., 2009. Molecular phylogenetics of a

clade of lowland tanagers: implications for avian participation in the Great

American Interchange. The Auk, 126(3), pp.635-648.

Trujillo-Arias, N., Calderón, L., Santos, F.R., Miyaki, C.Y., Aleixo, A., Witt, C.C., Tubaro, P.L. and Cabanne, G.S., 2018. Forest corridors between the central Andes and the southern Atlantic Forest enabled dispersal and peripatric diversification without niche divergence in a passerine. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 128, pp.221-232.”