Proposal (1024) to South

American Classification Committee

Treat Rhegmatorhina

berlepschi (Harlequin Antbird) as conspecific with R. hoffmannsi

(White-breasted Antbird)

Background:

The

genus Rhegmatorhina currently comprises five mostly allopatric species,

historically treated as separate species taxa based on diagnostic differences

in plumage (Cory and Hellmayr 1924, Zimmer and Isler

2003). Most are similar in behavior, and some taxa considered separate

species, such as R. berlepschi and R. hoffmannsi, are

undifferentiated vocally (Willis 1969). Although

differences in vocalizations are considered the major phenotypic marker for

species differences in antbirds, plumage differences may be important in

antbirds with ornamented plumages or conspicuous, colorful bare skin patches,

such as Rhegmatorhina (Skutch 1996, Zimmer and

Isler 2003). Genetic work documented structured mitochondrial genotypes

congruent with taxonomic boundaries, but shallowly diverged nuclear genotypes (Ribas et al. 2018, Harvey et al. 2020). The classification of the genus into five species seemed

reasonable given the information we had until now.

New

information:

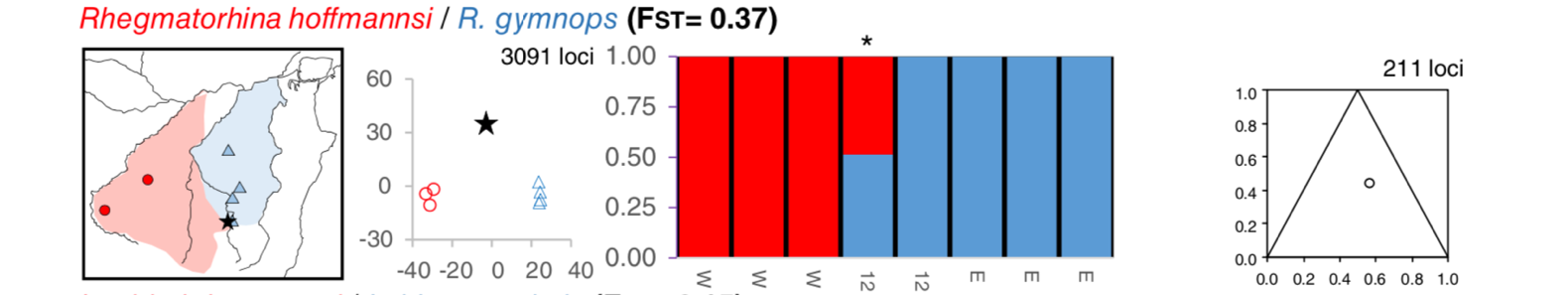

Recent

genetic research revealed extensive nuclear introgression between R. berlepschi

and R. hoffmannsi across hundreds of kilometers (Del-Rio

et al. 2022). The data is mostly consistent with neutral diffusion of

their nuclear genomes, although narrower

mitochondrial clines imply some selection maintaining mitochondrial

differentiation (Del-Rio et al. 2022). That

berlepschi and hoffmannsi hybridize extensively despite differences

in plumage (Del-Rio et al. 2022) indicates

that their plumage differences have little (if any) impact on reproductive

isolation. In summary, this data indicates weak overall reproductive isolation

between berlepschi and hoffmannsi.

Recommendation:

Given

the evidence of free nuclear gene flow between berlepschi and hoffmannsi

(Del-Rio et al. 2022), their taxonomic status

warrants reconsideration. The hybrid zone between these taxa is significantly

wider than those between many bird lineages considered conspecific (Price 2008). The correct taxonomic treatment seems

straightforward in light of the new evidence: berlepschi and hoffmannsi

are weakly reproductively isolated and, therefore, should be treated as

conspecific. The name hoffmannsi (Hellmayr, 1907) has priority over berlepschi

Snethlage, 1907, by some months.

References

Cory, C.

B., and C. E. Hellmayr (1924). Catalogue of birds of the Americas and the

adjacent islands in Field Museum of Natural History. Volume XIII, Part III.

Field Museum Press.

Del-Rio,

G., M. A. Rego, B. M. Whitney, F. Schunck, L. F. Silveira, B. C. Faircloth, and

R. T. Brumfield (2022). Displaced clines in an avian hybrid zone

(Thamnophilidae: Rhegmatorhina) within an Amazonian interfluve.

Evolution 76:455–475.

Harvey, M.

G., G. A. Bravo, S. Claramunt, A. M. Cuervo, G. E. Derryberry, J. Battilana, G.

F. Seeholzer, J. S. McKay, B. C. O’Meara, B. C. Faircloth, S. V Edwards, et al.

(2020). The evolution of a tropical biodiversity hotspot. Science

370:1343–1348.

Price, T.

(2008). Speciation in birds. Roberts & Company.

Ribas, C.

C., A. Aleixo, C. Gubili, F. M. d’Horta, R. T. Brumfield, and J. Cracraft

(2018). Biogeography and diversification of Rhegmatorhina (Aves:

Thamnophilidae): Implications for the evolution of Amazonian landscapes during

the Quaternary. Journal of Biogeography 45:917–928.

Skutch, A.

F. (1996). Antbirds and ovenbirds: their lives and homes. University of Texas

Press.

Willis, E.

O. (1969). On the behavior of five species of Rhegmatorhina,

ant-following antbirds of the Amazon basin. The Wilson Bulletin 81:363–395.

Zimmer, K.

J., and M. L. Isler (2003). Family Thamnophilidae (Typical Antbirds). In

Handbook of the birds of the world (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliot and D. A. Christie,

Editors). Lynx Edicions, pp. 448–681.

Rafael

Lima, July 2024

Vote tracking chart:

https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart968-1043.htm

Comments

from Stiles:

“YES. This is an easy choice, with a solid publication based upon abundant and

appropriate data - in contrast to all those recent ones to evaluate splits

based on fragmentary, incomplete and often conflicting pieces of data!”

Comments

from Lane:

“NO. Glaucia’s study is an intriguing one, but even she didn’t propose lumping

the two taxa because of the hybrid zone. The hybrid zone seems to be moving,

and doesn’t cover a large area (compared to the Myioborus case in Prop

1003, for example), suggesting that it is not a static system, but rather a

dynamic one that may end with one form swamping out the other.”

Comments

from Robbins:

“NO. As we have seen over and over, mitochondrial

data has limited utility and can mislead interpretations of taxonomy. Given the

nuclear data coupled with the reported lack of differentiation in primary

vocalizations, this seems to be rather straightforward in that these two should

be considered conspecific.”

Comments from Areta: “NO. I was waiting for

Glaucia´s input on this. The genetic situation is not as simple as described in

the proposal, and there are several nuances discussed in the meaningful paper

by Glaucia and collaborators. Meanwhile, in the face of a proper study measuring

vocalizations of Rhegmatorhina,

I decided to take a listen. The vocal similarities between hoffmannsi and berlepschi are striking and obvious even without

a quantitative study (and in agreement with the broad hybridization area found),

but what caught my attention are the also very similar vocalizations of gymnops (east of the Tapajós): songs and the

burry/churring calls sound pretty much identical. Glaucia´s work has also shown

a shallow divergence between gymnops and hoffmannsi/berlepschi.

Even if we know of no intergrades between berlepschi and gymnops (or is there any evidence for this?),

the seeming lack of vocal differences in their primary songs, minor plumage

differences (akin to those between berlepschi and hoffmannsi),

and shallow genetic divergence (see haplotype network in Del-Rio et al. 2022)

all would seem to indicate that, if east-Tapajós gymnops is given the chance to interact

reproductively with west-Tapajós berlepschi,

they would hybridize freely. Then I remembered a possibly relevant work and

found it: Weir et al. (2015; Evolution 69-7: 1823–1834) have found

hybridization close to the Tapajós headwaters (the black star in the figure

shows a hybrid between "hoffmannsi" and gymnops, I use quotation marks as it

is not clear to me how these birds looked like and what would happen with

phenotypes in that area):

“Weir et al. (2015) also add that "Mitochondrial sequence based estimates

of gene coalescence times between parental populations from the Rondonia and

Tapajos endemism centers ranged from just 0.7 Ma in L. iris / L.

nattereri and R. hoffmannsi / R. gymnops to 4.1 Ma in W.

poecilinota / W. vidua (Fig. 4)."

and "Ironically, the

taxon pairs with the most clearly differentiated plumage patterns, and which

have always been recognized as specifically distinct (R. hoffmannsi/R.

gymnops; L. nattereri/L. iris), are also the

youngest (<1 Ma) in our sample."

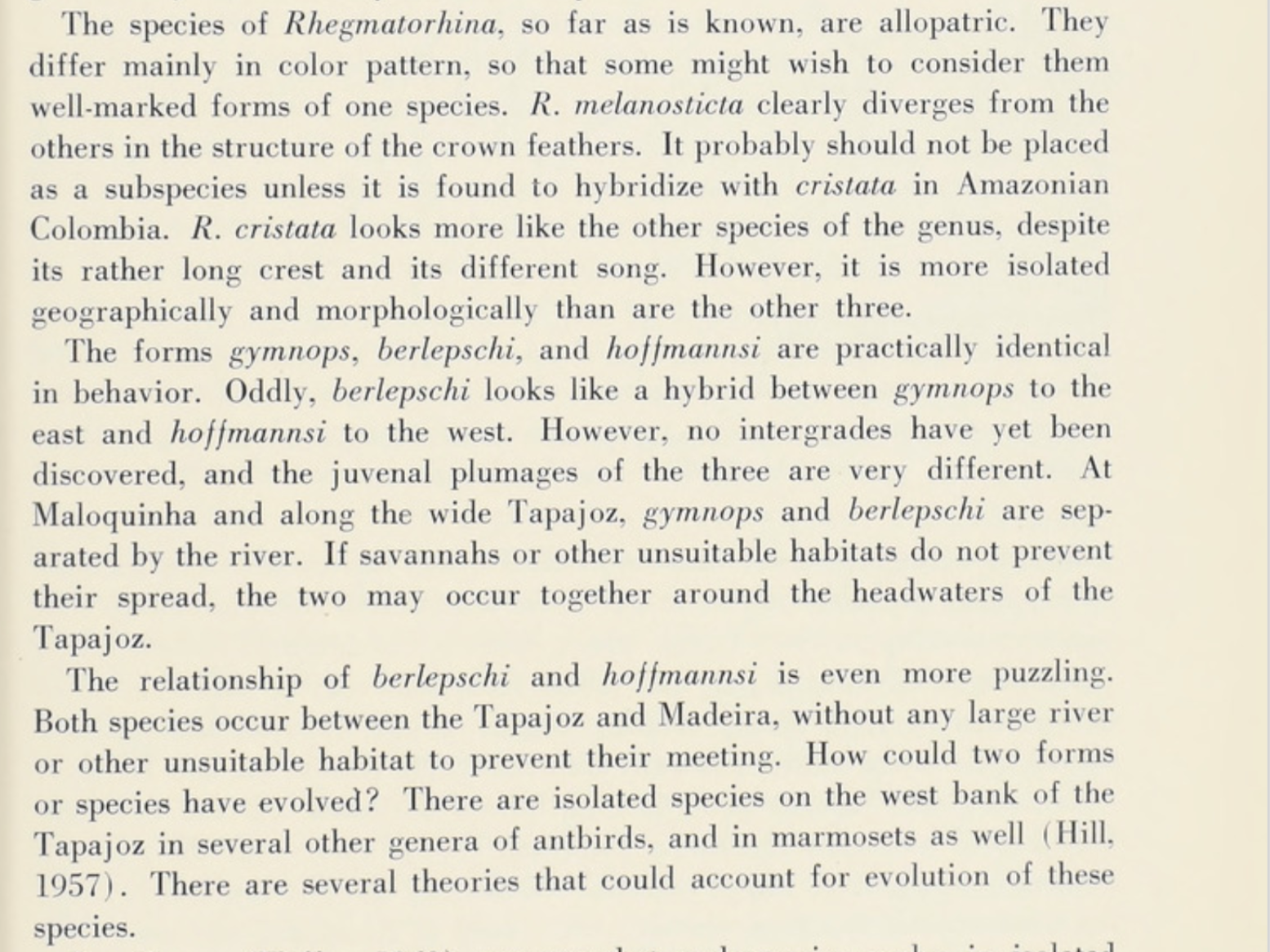

The discussion of Willis (1969) provides interesting

perspectives and somehow prepared the scenario for the modern findings: "The forms gymnops, berlepschi, and hoffmannsi are practically identical in behavior.

Oddly, berlepschi looks like a hybrid between gymnops to the east and hoffmannsi to the west."

And more:

“Finally, note that gymnops

was described by Ridgway in 1888, so that name would have priority

over berlepschi

and hoffmannsi. It seems

to me that a 3-way lump would be a reasonable treatment, but I would like to

hear from those with extensive Amazonian experience (I am eagerly waiting for

Bret´s and Kevin´s surely encyclopedic experience on this group). Even if at

present the Tapajós is impassable, I would like to see a deeper genetic and

vocal study in order to change our current taxonomic treatment. It seems that

the current 3-species treatment of the east-Madeiran

Rhegmatorhina is wrong,

but how many species should be recognised is debatable.”

Comments from Robb Brumfield (who has Jaramillo vote): “NO.

Hybridization between hoffmannsi

and berlepschi

is clearly extensive. The center of the hybrid zone is composed

almost entirely of recombinant individuals, and introgression of alleles

extends deep into the distributions of the two hybridizing taxa. These patterns

are typical of most avian hybrid zones for which we have genome-scale data.

However, Del-Rio et al (2021) found five diagnostic SNPs that fully

distinguish the two taxa and, using those, identified two individuals from the

hybrid zone as putative F1s. Both individuals were heterozygous at all

five diagnostic nuclear SNPs, and both had intermediate plumage. The presence

of these F1s is atypical

of most avian hybrid zones. The two F1s suggest that

strong reproductive

barriers exist between the two taxa in some parts of their nuclear genomes.

There are of course nuances to hybrid zone models that can change

interpretations based on assumptions, but it may be that strong selection on a

few nuclear loci is sufficient to maintain nuclear divergence between

hoffmannsi and

berlepschi. Whether the presence of strong reproductive

barriers at a few nuclear loci is sufficient evidence for species status is

unclear to me. Weir et al. (2015,

Evolution 69:1823)

found evidence of hybridization between

R. hoffmannsi and

R. gymnops where they

come into contact. My take is that

Rhegmatorhina is

reminiscent of Manacus

manakins, in that narrow hybrid zones occur wherever species come

into contact. Based on the data in

Del-Rio et al. (2015) and the fact that

Rhegmatorhina hybridization

and speciation is the focus of ongoing research, my vote is to not make any

taxonomic changes now.”

Additional comments from Rafael Lima: “I agree with Areta that a three-way lump

seems like the most reasonable approach, making gymnops the oldest name. That option initially escaped my

attention, and I thank Juan for pointing it out.

“I really

appreciate Robb’s thoughtful input on this matter and would like to offer some

additional reflections based on his comments.

“Robb mentions

that Rhegmatorhina hybrid zones are reminiscent of those in Manacus, where narrow hybrid zones occur wherever species come

into contact. However, I am not entirely convinced that the hybrid zone between

hoffmannsi and berlepschi can

be accurately described as "narrow." Of course, the terms

"narrow" and "broad" are subjective, but if the Rhegmatorhina hybrid zone is considered narrow, I

wonder what a "broad" hybrid zone would look like. The hybrid zone

between

hoffmannsi and berlepschi is, in fact, wider than many hybrid zones

typically referred to as "wide" in the literature, including those

between bird lineages considered conspecific (e.g., Price 2008).

“I completely

agree with Robb's point regarding whether strong reproductive barriers at a few

loci should suffice for species status when there is otherwise free gene flow

throughout the genome. I don’t have an answer for that question. However,

regardless of what the preferred cutoff should be, I believe this case may set

a precedent for future proposals. In the interest of consistency, those voting

"no" on this proposal might need to consider whether they would also

support splitting the many bird taxa currently classified as subspecies that

have similar hybrid zones and reproductive isolation levels. A "no"

vote might imply that bird lineages forming hybrid zones several hundred

kilometers wide, dominated by late-generation hybrids, should be considered

separate species under the BSC because of reproductive barriers at a few loci

amid widespread introgression elsewhere across the genome.

“I wonder why two

vocally undifferentiated antbird lineages that hybridize extensively over

hundreds of kilometers (i.e., berlepschi and hoffmannsi) should be regarded as separate

biological species while other similar antbird lineage pairs should be

considered conspecific. For instance, I recall the Thamnophilus capistratus proposal (Proposal 890). Why should Thamnophilus doliatus capistratus and the rest of Thamnophilus doliatus be considered conspecific when they may

have a hybrid zone less than 100 km wide, while Rhegmatorhina taxa with substantially wider hybrid

zones should be considerate separate species? The Thamnophilus capistratus proposal is merely an example that came

to mind, but there are numerous similar cases within the Thamnophilidae. While

I no longer think that capistratus should

necessarily be treated as a separate species, I do believe that consistent

application of criteria is crucial. If criteria are to be applied consistently

across taxa, we may need to reconsider species limits in many antbird taxa

based on the precedent potentially set by Rhegmatorhina.

“As a final note,

I personally view species limits as hypotheses formulated within the context of

currently available evidence. This is how I understand science to work, or at

least how it should ideally function, in my opinion. We should make decisions

based on the evidence at hand, not on potentially different evidence that may

emerge in the future. Therefore, I am not entirely convinced by the argument

that taxonomic changes should be postponed due to ongoing research on Rhegmatorhina hybridization. If we avoid taxonomic

changes because of ongoing research, we might never make any changes. I believe

the decision here should be as straightforward as the recent NACC decision to

treat Corvus caurinus as conspecific with C. brachyrhynchos, for example. Common to both cases is the existence of recent

studies providing crystal clear evidence for extremely weak reproductive

isolation between the two lineages involved. If Del-Rio et al. (2021) did not

provide sufficient evidence of weak reproductive isolation between berlepschi and hoffmannsi, I wonder what future research could

possibly demonstrate conspecificity between these two taxa. Should that

evidence arise, we can adjust accordingly, as we scientists routinely do.”

Comments from Claramunt: “Tentative NO. I was going to

vote Yes, persuaded by Rafael’s proposal and a cursory examination of Glaucia’s

superb* paper. R. berlepschi and hoffmannsi are clearly

hybridizing and forming a relatively wide hybrid zone with intergradation of

traits, and admixture of genomes. Songs are the same and the plumage

distinction didn’t impede interbreeding. It seems that there are no barriers to

interbreeding. I’m not convinced by the argument about the purported

identification of F1 individuals. In a sample of 222 individuals and only five

diagnostic loci, it would not be hard to find a handful of specimens that look

like F1s by chance, just by being heterozygotes for the five loci. Unless I’m

missing something, I don’t see how this method would lead to correct

identification of F1s. And it seems that it would be impossible for true F1s to

be formed anyway given that there are no parental pure forms in geographic

proximity.

“The unavoidable conclusion under the biological species concept

is that these two taxa should be lumped. Many recent proposals for species

status are being rejected because of the speculation of potential interbreeding

in hypothetical sympatry. Well, here there is actual evidence of widespread

interbreeding and no signs of reproductive barriers.

“Having said that, it is possible that the degree of genomic

admixture is being overestimated. Each SNP has very little information about

genealogy, and at least some methods used to analyze SNPs do not take a

historical/evolutionary perspective, e.g. allele A suggests ancestry X if A is

frequent in X, regardless of whether A is the ancestral state or not. If allele

A is ancestral, sharing it does not indicate close relationships in the

genealogical network (basic phylogenetics applied to genealogies). I’m going to

do some research to see if I can back up my suspicion with some evidence. In

the meantime, I feel entitled to suspect that the width of the SNP clines and

the degree of admixture is being overestimated. This may be a case of a, maybe

not narrow but relatively constrained hybrid zone (200km?) on genomic

backgrounds that are differentiated. Then the question would be whether the

hybrid zone is a tension zone maintained by some sort of selection against

hybrids or assortative mating. Is the hybrid zone stable or moving? Is it

shrinking or expanding? There may be room for still considering these two taxa

separate species even if hybridizing. For that reason I tentatively vote NO,

waiting for more comments and discussion about this case, that may set a

precedent for decisions based on this kind of scenario.”

Comments from Del-Rio: “NO. It is a complicated case,

primarily because most of the cases we analyze here at SAAC are based on

plumage, song, morphology, a few genes, or—in the best-case scenarios—reduced

representation genomic data (usually less than 1% of whole genomes). In the

case of Rhegmatorhina, however, we have all of the above plus a

high-quality whole genome and whole genome resequencing data at a decent

coverage for almost one hundred individuals.

“In the era of whole genomes, let’s see what happens. How are we

going to define what constitutes strong versus weak levels of reproductive

isolation?

“The results and ideas in the Evolution paper (Del-Rio

et al., 2022) have evolved over the last couple of years. I won’t go into

details here, but my most recent results show: (1) several genomic islands of

differentiation between Rhegmatorhina hoffmannsi and R. berlepschi;

(2) strong differential selection indicating assortative mating on regions of

the genome involved in the definition of plumage coloration (Del-Rio et al in

prep.).

“I vote NO because: (1) The argument that the Rhegmatorhina

hybrid zone is too wide is flawed, as the hybrid zone width varies depending on

which part of the genome is being analyzed. Some regions of the genome and some

plumage features show narrow and steep clines. That’s the beauty of the

system—a unique opportunity to understand which parts of the genome are

preventing species fusion; (2) Additionally, with the available methods, the

complex geography of the system leads to an overestimation of cline widths; (3)

I am still working to understand how much these islands of genomic

differentiation translate into reduced fitness in hybrids; (4) I am still

trying to perform experiments to test for assortative mating based on plumage

and vocal characters; (5) I am still analyzing vocal and environmental

variation between the two forms; (6) In Brazil, “subspecies” status is rarely

considered in conservation efforts, and R. berlepschi might become a

species of concern with the advance of deforestation in Amazonia.

“Regarding the idea of gene flow with R. gymnops, my data

does not corroborate the findings of Weir et al. (2015) so far. Again, this is

another aspect I am still investigating.”

Comments from Del-Rio: “NO. It is a complicated case,

primarily because most of the cases we analyze here at SAAC are based on

plumage, song, morphology, a few genes, or—in the best-case scenarios—reduced

representation genomic data (usually less than 1% of whole genomes). In the

case of Rhegmatorhina, however, we have all of the above plus a

high-quality whole genome and whole genome resequencing data at a decent

coverage for almost one hundred individuals.

“In the era of whole genomes, let’s see what happens. How are we

going to define what constitutes strong versus weak levels of reproductive

isolation?

“The results and ideas in the Evolution paper (Del-Rio et

al., 2022) have evolved over the last couple of years. I won’t go into details

here, but my most recent results show: (1) several genomic islands of

differentiation between Rhegmatorhina hoffmannsi and R. berlepschi;

(2) strong differential selection indicating assortative mating on regions of

the genome involved in the definition of plumage coloration (Del-Rio et al in

prep.).

I vote NO because: (1) The argument that the Rhegmatorhina hybrid

zone is too wide is flawed, as the hybrid zone width varies depending on which

part of the genome is being analyzed. Some regions of the genome and some

plumage features show narrow and steep clines. That’s the beauty of the

system—a unique opportunity to understand which parts of the genome are

preventing species fusion; (2) Additionally, with the available methods, the

complex geography of the system leads to an overestimation of cline widths; (3)

I am still working to understand how much these islands of genomic

differentiation translate into reduced fitness in hybrids; (4) I am still

trying to perform experiments to test for assortative mating based on plumage

and vocal characters; (5) I am still analyzing vocal and environmental

variation between the two forms; (6) In Brazil, “subspecies” status is rarely

considered in conservation efforts, and R. berlepschi might

become a species of concern with the advance of deforestation in Amazonia.

“Regarding the idea of gene flow with R. gymnops, my data

does not corroborate the findings of Weir et al. (2015) so far. Again, this is

another aspect I am still investigating.”

Additional comments from Rafael Lima: “Considering the comments above, it seems

unlikely that any amount of evidence or argument will alter the trajectory of

this proposal. Nevertheless, I would like to share some final thoughts:

“1. My impression

from all this is that there is a strong reluctance to change, as most arguments

for maintaining the current classification hinge on predictions about ongoing

studies or conservation-oriented reasoning, rather than drawing much more straightforward

conclusions from the available evidence. While I’ve already expressed my

thoughts on this, I feel it’s important to reiterate that taxonomic decisions

should be grounded in the evidence we currently have, not on what future

research might reveal. I fully understand the desire for taxonomic stability,

especially for those working in downstream fields that use checklists like

this. However, prioritizing stability over scientific rigor severely undermines

taxonomy as a discipline. I therefore urge that decisions be made based on

present evidence rather than futurology.

2. The conclusion

that these taxa should be considered conspecific appears so evident in the

results of Del-Rio et al. (2022) that I initially thought this proposal would

be straightforward. However, based on the comments above, it seems I may not

have fully elaborated on my interpretation of these results. One key point I

thought would be clear to anyone reviewing the results from Del-Rio et al.

(2022) is the modality of the hybrid zone. The modality of a hybrid zone is a

critical indicator of the strength of reproductive isolation between two

interbreeding populations (nicely reviewed in Jiggins & Mallet 2000, Trends

Ecol. Evol. 15: 250-255). In Rhegmatorhina, the hybrid zone is clearly

unimodal. Most importantly, it is late-generation hybrids that dominate. I

can’t think of a more compelling indication that overall reproductive isolation

is very weak in this system. If assortative mating existed, the zone would be

bimodal. If strong postzygotic isolation occurred, through selection against

hybrids or genetic incompatibilities, first-generation hybrids, not

backcrosses, would dominate. Neither assortative mating nor postzygotic

isolation seems to be in play.

“Glaucia mentions

the presence of steep clines, possible assortative mating, and reduced hybrid

fitness as potential reasons to maintain the taxa as separate species. Theory

predicts that as differentiation accrues between any two populations, some

degree of reproductive isolation will almost always be present. Unsurprisingly,

it is not unusual to observe steep clines, assortative mating, and reduced

hybrid fitness within species. The critical question when applying the

BSC is not whether these phenomena are at play, but whether they are strong

enough to prevent the fusion of the populations involved. In the case of Rhegmatorhina,

there are some narrow clines, but they exist alongside many broader ones. Are

these narrow clines causing moderate or strong overall reproductive isolation?

The evidence suggests not. Regarding assortative mating and hybrid fitness, the

unimodal nature of the hybrid zone makes it implausible that either is

occurring at a significant level. It is not entirely clear to me how there could

be assortative mating given that there are no parentals in the hybrid zone, or

how hybrids could suffer from reduced fitness when backcrosses are so

predominant. Even if we assume some degree of non-random mating and reduced

hybrid fitness, the current evidence strongly suggests that these putative

barriers are insufficient to prevent extensive gene flow. Gene flow remains

abundant, despite any potential barriers. The way I see it, the burden of proof

is clearly on the current multiple-species treatment, for which the evidence

has long been weak (as noted by Willis 1969).

“Finally, it is

not true that subspecies taxa are not considered in conservation efforts in

Brazil. The Brazilian Red List of Threatened Species does include

subspecies-level assessments for birds. However, this point should not even be

a factor in this discussion, as the decision here should be independent of

conservation concerns. (Taxonomic decisions motivated by conservation have

already been addressed in other proposals, so I will refrain from elaborating

further.) Otherwise, species limits in Rhegmatorhina will, after this

voting, be based more on speculation and conservation-oriented reasoning than

on existing evidence.”

Additional comments from Claramunt: “I change

my vote to YES. At the end of the day, I’m with Rafael on this. The evidence of

introgressive interbreeding is just overwhelming. There are no signs of

selection against hybrids: the paper concludes that neutral diffusion cannot be

rejected. There are some hints of “islands of differentiation” and reduced

hybrid fitness in some part of the genomes, but those are clearly not

sufficient as reproductive barriers and genes are profusely flowing in both

directions. The conclusion is inescapable under any species concept:

reproductive isolation is nonexistent, diagnosability is broken, lineages are

intertwined.

“It doesn’t get better than that when it comes to evidence of

interbreeding. It is not only the absolute width of the hybrid zone what

matters but how broad it is in comparison with the rest of the distribution of

the species involved. In this case, the tail of the hybrid zone gets so deep

into the berlepschi territory that there are barely any pure berlepschi

anymore (see the ancestry analysis in Fig. 3). The paper by Glaucia et al. is

superb, and we are in a period in which we need to pay close attention to

analyses of genomic data. The genomic revolution would likely change our

perspectives on how we delimit species and even on what species are. But today,

under current species concepts, the evidence in this case is conclusive.

Keeping berlepschi and hoffmannsi as separate species in the face

of seemingly free introgressive hybridization would be a radical departure from

a century of application of the biological species concept. If our mission is

to produce a coherent and evidence-based classification, we can’t maintain berlepschi

and hoffmannsi as separate species. There is no better evidence of

interbreeding than genomic analyses like this. Plumage and song differences and

similarities, and playback experiments, can suggest reproductive compatibility,

but never prove it. We can’t ignore the best evidence in this case and at the

same time lump other taxa based on much lower quality evidence, in many cases,

educated speculation about what birds would do if in sympatry. Is this a

breaking point in our approach to species delimitation? Actual evidence of

introgressive hybridization does not count anymore? We must surrender to the

evidence if we are to produce a scientific classification.”

Comments from Remsen: “NO. I have looked at the series

assembled by Glaucia and colleagues from the contact zone. Although there are some obvious hybrids,

there are also at least as many phenotypically pure birds from the. contact

zone, and this suggests that mating is not random, thus supporting separate

species treatment under the BSC.”

Comments from Zimmer: “YES, although not an

enthusiastic yes. It pains me, because

these birds are near and dear to my heart, and because both forms are truly

exquisite in their parental phenotypic states.

However, I have examined whole museum trays of obvious hybrids, and the

evidence for a relatively broad hybrid swarm, with no pure parentals of either

type, and apparently, even very few F1 hybrids, appears overwhelming. I’ve gone back and forth on this, given that

Glaucia, who, presumably, knows these birds better than anyone since Ed Willis,

is not advocating for lumping at this time.

On the one hand, lumping hoffmannsi and berlepschi does

solve a conundrum that puzzled Willis and all Rhegmatorhina enthusiasts

since – how, in a group where all of the species have allopatric distributions

separated by major rivers, can two species be found in the same interfluve,

without an obvious geographic barrier, and still maintain isolation? And now, we know, they don’t. Of course, we also now know, from all of the

relatively recent work done in the Aripuanã and Roosevelt drainages, and, to a

lesser extent, along the Teles Pires, that the complex

geologic/hydrographic/hydrologic history of the Madeira-Tapajós interfluve has

resulted in a present-day situation in which relatively small rivers may

present barriers sufficient to maintain isolation and prevent secondary contact

of some understory passerines of low vagility.

That fact, coupled with the complex physical history of the interfluve,

probably provides the answer to Willis’s question: “The relationship of berlepschi and

hoffmannsi is even more puzzling. Both

species occur between the Tapajoz and Madeira, without any large river or

unsuitable habitat to prevent their meeting.

How could two forms or species have evolved?” The one thing that gives me pause over the

decision to lump these two species, is the same thing that I circle back to

when considering similar hybrid zones between several of the larger species of

North American Larus -- how, in

the face of broad hybrid zones, in which mating appears non-assortative and

pure parental types are outnumbered by hybrids, do we explain the maintenance

of pure parental phenotypes over large swaths of the parental ranges? The distributions of hoffmannsi and

(especially) berlepschi are not all that large to begin with. With ongoing regional deforestation eroding

these already small ranges, I would think that in the absence of some

meaningful pre or postzygotic barriers to reproduction, the hybrid zone would

expand to the point of swamping both parental phenotypes. That this has not happened, makes me think

that there are still some factors in play that are promoting isolation, or at

least, slowing allelic penetration from one genome into the other outside of

the hybrid zone. I would like to know if

the hybrid zone is stable or labile, and, if the latter, is the expansion

unidirectional or is it advancing in both directions. Despite all of these reservations, I am,

ultimately, persuaded by the well-reasoned arguments of Rafael and Santiago,

and have to concede that the weight of the evidence at hand leads to the

conclusion to lump hoffmannsi and berlepschi. Conversely, I am not supportive, on current

evidence, of expanding this to include gymnops in a 3-way lump. Despite obvious vocal and behavioral

similarities between the 3 taxa, there is no evidence that I have seen, of a

documented hybrid zone between gymnops and hoffmannsi, even if

Weir et al. (2015) are reporting a single putative hybrid from the narrow

headwater region of the Tapajós. That’s

a far cry in my estimation, from the situation with hoffmannsi and berlepschi. I don’t doubt that gymnops and hoffmannsi

may be only shallowly diverged genetically from one another, but extrapolating

that to support speculation about how the two would behave were they to come

into contact seems premature, given that for the vast majority of their

respective ranges, the two are separated by the length of the mighty

Tapajós. The headwaters region, where

they may contact one another, is also within the notorious Arc of Deforestation

at the southern fringes of Amazonia and would seem an unlikely venue for an

expanding hybrid zone between two terra firme interior-inhabiting

species that are only marginally in contact.

Note Glaucia’s comment that her data, to this point, does not

corroborate the findings of Weir et al (2015) with respect to gene flow with gymnops.”