Proposal (1028) to South

American Classification Committee

Treat Synallaxis

cinerea as conspecific with S. ruficapilla

The

Synallaxis ruficapilla complex currently includes three species taxa:

the Rufous-capped Spinetail (S. ruficapilla), Bahia Spinetail (S.

cinerea), and Pinto’s Spinetail (S. infuscata). Also part of the

complex is a geographically isolated population in the Brazilian state of Mato

Grosso, often cited as a possibly undescribed taxon

(Whitney and Cohn-Haft 2013, Batalha-Filho et al. 2013) but which may merely

represent a range extension of ruficapilla. For a more in-depth

overview of the complex, the reader is referred to the work of Stopiglia et al. (2013).

Phenotype

Stopiglia et al. (2013) examined geographic variation in plumage,

morphometrics, and vocalizations. They found that only two populations in the

complex are phenotypically diagnosable: one corresponding to infuscata and the

other comprising the rest of the complex.

Genotype

Genetic

research identified five mitochondrial lineages within the complex: one

corresponding to infuscata, one to cinerea, one to the Mato

Grosso population, and two lineages within ruficapilla (Batalha-Filho et al. 2013,

2019). All have very shallow nuclear divergence (Batalha-Filho et al. 2013,

2019; Harvey et al. 2020).

Recently, Batalha-Filho

et al. (2019) analyzed two mitochondrial genes, two autosomal nuclear introns,

and three Z-linked genes from many individuals of cinerea and ruficapilla. They discovered a wide hybrid zone between the two near the

Jequitinhonha River. One Z-linked locus showed a narrow cline (~ 28 km), while

all other loci showed wide clines (~ 179–529 km).

In summary, all taxa, including those

that are phenotypically indistinguishable, are diagnosable units with respect

to mtDNA. Additionally, there are other populations with equivalent levels of

mtDNA divergence that are unnamed within the complex, namely the Mato Grosso

population and one population within ruficapilla. The narrow cline for one Z-linked locus suggests some selection on

the hybrid zone between cinerea and ruficapilla, although there is extensive gene flow on the rest of the genome.

How many taxa?

The

S. ruficapilla complex presents a challenging situation for

classification. The

geographic phenotypic variation in the S. ruficapilla complex is similar to that of

several other bird species complexes along the Atlantic rainforest, with a

phenotypically diagnosable populations restricted to north of the São Francisco

River and two somewhat differentiated, but not diagnosable, populations south

of that river (e.g., Lima et al. 2024). In this broader context, S. cinerea seems to be another example of

an avian taxon originally described from a small sample (Pacheco and Gonzaga

1995) that eventually proved undiagnosable with a greater sample (Stopiglia et

al. 2013).

Given that cinerea and ruficapilla are

phenotypically undistinguishable (Stopiglia et al. 2013), the only currently available basis for

recognizing cinerea as a valid taxon (regardless of rank) is

diagnosability on the basis of mtDNA and some Z-linked loci (Batalha-Filho

et al. 2019). Regarding rank,

extensive hybridization between cinerea and ruficapilla suggests that

the current treatment of the two as separate biological species may be in

error.

I recommend a YES vote to recognize as cinerea and ruficapilla as

conspecific, based on the recent evidence of extensive gene flow and the lack

of phenotypic diagnosability between the two.

References:

Batalha-Filho,

H., M. Irestedt, J. Fjeldså, P. G. P. Ericson, L. F. Silveira, and C. Y. Miyaki

(2013). Molecular systematics and evolution of the Synallaxis ruficapilla

complex (Aves: Furnariidae) in the Atlantic Forest. Molecular Phylogenetics and

Evolution 67:86–94.

Batalha-Filho,

H., M. Maldonado-Coelho, and C. Y. Miyaki (2019). Historical climate changes

and hybridization shaped the evolution of Atlantic Forest spinetails (Aves:

Furnariidae). Heredity 123:675–693.

Harvey, M.

G., G. A. Bravo, S. Claramunt, A. M. Cuervo, G. E. Derryberry, J. Battilana, G.

F. Seeholzer, J. S. McKay, B. C. O’Meara, B. C. Faircloth, S. V Edwards, et al.

(2020). The evolution of a tropical biodiversity hotspot. Science

370:1343–1348.

Lima, R.

D., A. C. Fazza, M. Maldonado-Coelho, C. Y. Miyaki, and V. Q. Piacentini

(2024). Taxonomic revision of the Scaled Antbird Drymophila squamata

(Aves: Thamnophilidae) reveals a new and critically endangered taxon from

northeastern Brazil. Zootaxa 5410:573–585.

Pacheco, J.

F., and L. P. Gonzaga (1995). A new species of Synallaxis of the ruficapilla/infuscata

complex from eastern Brazil (Passeriformes: Furnariidae). Ararajuba 3:3–11.

Stopiglia,

R., M. A. Raposo, and D. M. Teixeira (2013). Taxonomy and geographic variation

of the Synallaxis ruficapilla Vieillot, 1819 species-complex (Aves:

Passeriformes: Furnariidae). Journal of Ornithology 154:191–207.

Whitney, B.

M., and M. Cohn-Haft (2013). Fifteen new species of Amazonian birds. In

Handbook of the birds of the world. Special volume: new species and global

index (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliot, J. Sargatal and D. A. Christie, Editors). Lynx

Edicions, pp. 225–239.

Rafael D.

Lima, July 2024

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Comments from Claramunt: “YES. I

studied the type series of cinerea at the AMNH myself, and I could not

find any consistent difference with specimens of ruficapilla. The polymorphism

in the song is intriguing, but it is not separating two taxonomic groups, as

demonstrated by Stopiglia et

al. (2012). My impression is

that cinerea should not be recognized even at the

subspecies level; it’s a full synonym of ruficapilla.”

Comments from Robbins: “YES for

reasons outlined in the proposal.”

Comments from Stiles: “YES: the

proposal seems clear and logical given the evidence adduced.”

Comments

from Zimmer: “YES, for reasons nicely summarized in

the Proposal. I do wonder as to whether

Stopiglia et al. (2013) included specimens of the still-undescribed Mato Grosso

birds in their study, and, if so, how many specimens of said population they

examined. Hard for me to imagine that

those birds are not diagnosable, or, that they represent merely a range

extension of ruficapilla – if so, it would not represent just a

significant range extension, but it would also mean that a bird that occupies

Atlantic Forest, including montane forest, over most of its rather wide range,

has a string of isolated populations occupying lowland Amazonian forest-edge

between the Xingu basin and Alta Floresta.”

Comments

from Josh Beck: “Despite not having had time to do an exhaustive

analysis I spent quite some time listening to vocalizations on XC based upon my

memory of the voice of these two taxa being distinctive. I am surprised by the

fact that the vocalizations were not discussed in the proposal and haven’t been

mentioned yet. They are instantly diagnosable by voice. My initial

investigation in Xeno Canto of recordings along the species boundaries didn’t

reveal any intermediate or out of place vocalizations, at least initially

suggesting a clean boundary between the two species based on voice.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso: “YES. Still, I was also surprised that

vocalizations were not discussed in the proposal, especially when many of our

decisions are heavily influenced by song differences. Still, the degree of

hybridization and the lack of diagnostic phenotypic differences seem indicate

that the species-level rank of S. cinerea is not warranted. That said, it looks like a neat system to

study vocal interactions in and out of the contact zone.”

Comment from Rafael Lima: “I

would just like to clarify that vocalizations are addressed in the proposal. It

is explicitly mentioned that Stopiglia et al. (2013) examined geographic

variation in plumage, morphometrics, and vocalizations. As summarized in

the proposal, cinerea was not diagnosable from ruficapilla

in any of the examined phenotypic traits, including vocalizations. I would be

curious to learn more about the specific differences that Josh identified in

the xeno-canto recordings, given that his conclusion that the two taxa are ‘instantly

diagnosable by voice’ contrasts with Stopiglia et al.'s (2013) conclusion.”

Comments from Lane: “NO. I

have to agree with Josh here, and I’m a bit amazed that Stopiglia et al. didn’t

detect vocal differences between S. cinereus and S. ruficapillus…

it actually should be pretty obvious to any listener! Rather than the multi-note

“dddd-dic” with an obvious pause after each song phrase, it’s a more

rapidly-given “d-dic” with very brief pauses or a very rapid series

(d-dic-d-dic-d-dic…) with no pauses at all. If you listen to recordings from

the geographically most proximal populations of S. ruficapillus, they

show no variation overlapping S. cinereus.”

Additional comments from Josh Beck: “Stopiglia et al (2013) basically divided

the vocalization of either species into two phrases – with cinerea

essentially being a one note first phrase and a one note final phrase, and ruficapilla

being a fast series then a final note. They then state “The number of elements

varies geographically, with zero to six elements north of the Jequitinhonha

River and one to seven elements south of the Jequitinhonha River. Thus, this

geographically variable character cannot be considered diagnostic using the

criteria put forward by Isler et al. (1997).

“A key issue appears to be that Stopiglia included vocal samples

from Chapada Diamantina in their analysis of cinerea and then found the

result that “Our analysis shows that the number of elements in the first

syllable of S. whitneyi ranges from zero (absent, see ‘‘Methods’’) (Boa

Nova, Bahia and Almenara, Minas Gerais) to six (Bonito and Lenc ̧o ́is, Bahia)

(Fig. 12b–h), whereas in S. ruficapilla it ranges from one (Poc ̧o

Dantas, Minas Gerais), to seven elements (Rio Novo, Minas Gerais) (see Table

3).” Worth noting that Bonito and Lençois are precisely the Chapada Diamantina

samples and are where they found a high number of introductory notes that they

(apparently) did not find in the “typical” cinerea range.

“The paper doesn’t provide details of how many notes were

associated with each sampled individual or with each sampling region, nor does

it provide any mean number of notes data, and unfortunately their recordings

are not publicly available and the email for the Elias Coelho Sound Archive

bounces.

“Regardless of how you try to read between the lines of their

analysis of vocal non-diagnosability, and with the caveat that we don’t have

access to Stopiglia’s recordings, publicly available recordings (XC and

Macaulay) paint a quite different picture and suggest that the birds are

largely readily diagnosable to one of the three vocal groups: classic ruficapilla,

classic cinerea, and classic infuscata. Of course, as Santiago

pointed out, the birds in Chapada Diamantina fit the ruficapilla vocal

pattern but Batalha-Filho’s haplotype network places them with cinerea.

“Per Van’s request here is an attempt to summarize typical

vocalizations, to relate them to Stopiglia’s terminology and findings, to

provide a couple links to typical vocalizations:

cinerea - a repeated hiccupping vocalization that consists of a softer

first note / phrase and a harder/louder second note/ phrase. At times in a lot

of the recordings it sounds like there is a bit of a “1 and a half note” first

phrase if you listen in detail:

https://xeno-canto.org/938458 (this is a good example to my ear of

being able to hear more introductory notes)

ruficapilla - a longer series of introductory notes

that also changes the timing between the final notes by quite a bit, changing

the feel of how fast the bird is vocalizing - though it is of course hard to

know what role the bird’s state of agitation plays in how often it repeats its

song

https://xeno-canto.org/385431 (one of the faster recordings I can find

where the introductory notes are more quickly stuttered, but in this case the

bird is perhaps less agitated and is not repeating the song as frequently)

Chapada Diamantina birds - basically sound

like ruficapilla

infuscata - essentially just repeats what would be

the second phrase of the vocalizations of ruficapilla/cinerea,

sometimes with 3-4 notes, sometimes in a long series - here as examples of both

the short and long series:

https://xeno-canto.org/712287 (a duet of shorter series)

https://xeno-canto.org/843883 (a long series from one bird)

The best recordings I can find from near

the zone of contact / intergradation that might represent intergradation are

these from near the Mata do Passarinho reserve:

https://ebird.org/checklist/S62644490

https://ebird.org/checklist/S52374129

https://ebird.org/checklist/S43462202

And these from a bit further north from

XC:

“I didn’t find any recordings of the birds from Vila Rica region

of Mato Grosso, but they don’t seem to be under discussion here so not really

relevant.

“With the caveat that I’m doing this as a layman, having now

listened to a few hours of audio and read the involved papers a couple times,

Stopiglia’s vocal analysis is pretty hard to extract meaningful information

from given their inclusion of Chapada Diamantina birds in cinerea and

the presentation of results that lack sufficient details about mean number of

introductory notes and about how many outlying recordings they had and from

precisely where. The neat page of clinal graphs is particularly useless in my

opinion if one wants to look at it in terms of contact zones and considering

the Chapada Diamantina birds might not just be cinerea. It would be nice

to have access to all their vocal material but based upon what is available and

field experience, I personally view the statement that “this geographically

variable character cannot be considered diagnostic” to be fairly misleading. The

fact that the vocal types and the haplotype network don’t line up neatly is

certainly interesting with respect to the Chapada Diamantina birds (and I won’t

try to get involved in the genetics discussion), but the vocal types as known

are quite diagnosable and there is a lack of available recordings from near to

the contact zone to try to examine the vocal case in that region in more

detail.”

Comments from Remsen: “NO. With

the comments from Dan and Josh, this all needs to be straightened out formally

before making a taxonomic decision.”

Comments from Areta: “I´ve been scratching my head for several

years on the Stopigila et al. (2013) paper on this complex, until Batalha-Filho

et al. (2019) appeared, and everything made more, but not complete, sense. It

is clear that there is a transition area, in which cinerea and ruficapilla

hybridize (seemingly to the south and north of the Jequitinhonha river), while

the Chapada Diamantina populations with ruficapilla voice and cinerea

mtDNA can perhaps be explained away by former reproductive contact between

them, which does not seem to have carried much into their genomes (or has it?)

or phenotypes. It is relevant that this population is so remarkably ruficapilla-like

in vocalizations, or at least that it seems to sound like birds with mtDNA

placing them in the northern ruficapilla

clade. The divergence between cinerea and ruficapilla is quite

recent (around 0.9 million years; although there is a wide posterior

probability interval: 95% highest posterior density [HPD] 0.541–3.461 mya). The

bioacoustic analyses in Stopiglia et al. (2013) could have been neater, but

nonetheless they seem to have broadly predicted the geographic patterns later

uncovered in genetic terms: there is an area of vocally intermediate birds more

or less where the genetics indicate admixing. I don´t like the lumping of all

the vocalizations in "5 degree blocks", especially because one of the

blocks seems to include samples to the north and south of the Jequitinhonha

river where one would like to see in more detail what is going on, and also

because the vocally ruficapilla-like Chapada Diamantina population has

been subsumed under the cinerea vocal dataset. Thus, I have asked Marcos

Raposo and Renata Stopiglia for a table of raw data, to see if we can refine

our understanding of what is going on here.

“However, preliminarily, the data seems

to be showing fairly stable and diagnostic vocal types that have a transition

area in which they blend into something intermediate. The question seems one of

degree here, as the zone of intermediacy is there, but it apparently has not

been thoroughly characterized at the genetic or vocal level. In the end, it

seems that the question is whether what is going on at the interaction zone is

relatively free interbreeding or conversely the populations are just hybridizing

over a narrow front. Although some nuclear gene clines seem rather wide,

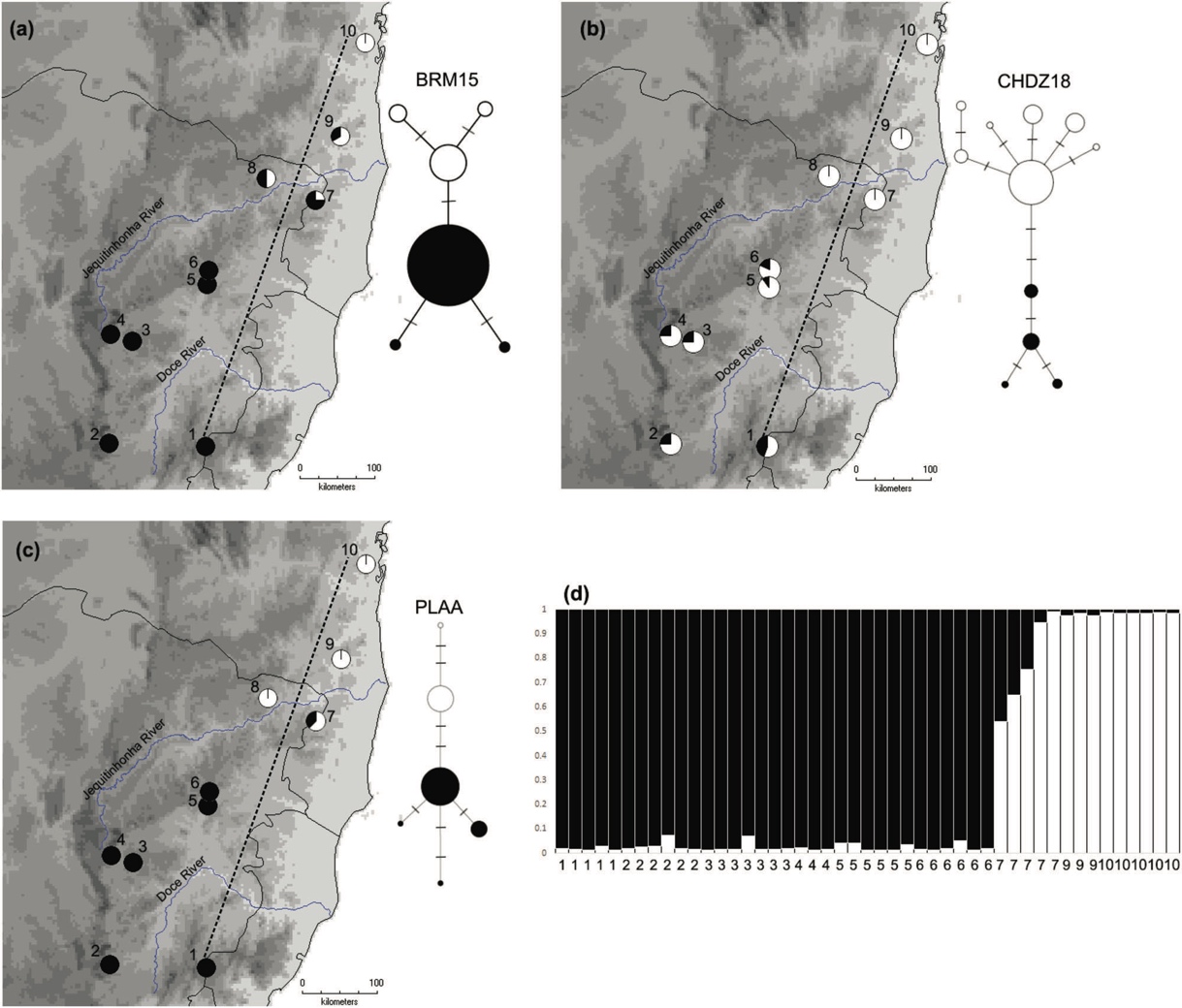

Batalha-Filho et al. (2019) state that "these

analyses suggest that introgression is somewhat geographically limited, despite

hybrids being common at this locality." (p. 688; referring to locality 7

in their study), and also that "Structure results indicated a higher level

of admixture in locality 7, with an abrupt decrease in introgression levels

away from this population (Fig. 2d)" (pp. 683-684). The cline widths shown in their

Figure 4 are of course influenced by the sampling localities, and I wonder

about the nuclear composition of the Chapada Diamantina population (is it, for

the sampled genes, just like other cinerea populations?). They conclude that

there is likely selection against the hybrids, and possibly incomplete lineage

sorting as well in nuclear DNA. Thus, I would take the cline widths with a

grain of salt until there are genomic data including more nuclear genes. The

proposal states that "The narrow

cline for one Z-linked locus suggests some selection on the hybrid zone between

cinerea and ruficapilla, although there is extensive gene flow on

the rest of the genome", but such an extensive gene flow at the

genome level remains to be shown and this conflicts with the view of

Batalha-Filho et al. (2019). At any rate, one has at least to accept

that there is no full reproductive independence between cinerea and ruficapilla,

with the second question being whether there is "essential"

reproductive independence between them under a BSC framework.

“Before casting my vote,

I would like to examine the raw vocal dataset used by Stopiglia et al. (2013)

in more detail. For example, it could well be that there is clinal variation in

the number of notes in Synallaxis

ruficapilla, with an abrupt switch to the S. cinerea song through a small area in which birds sound

intermediate (in consonance with what genetic data indicates). Also, the

southern population of ruficapilla

has a distinctive inflection at the onset of the final note, which seems to be

lacking further north, and which might also exhibit clinal variation. Thus,

distinguishing several different scenarios is the task we should be up to, and

I am not sure that the available data allows us to clearly distinguish between

them. The case is difficult, given the lack of clearcut limits that are the

hallmark of classic speciation.

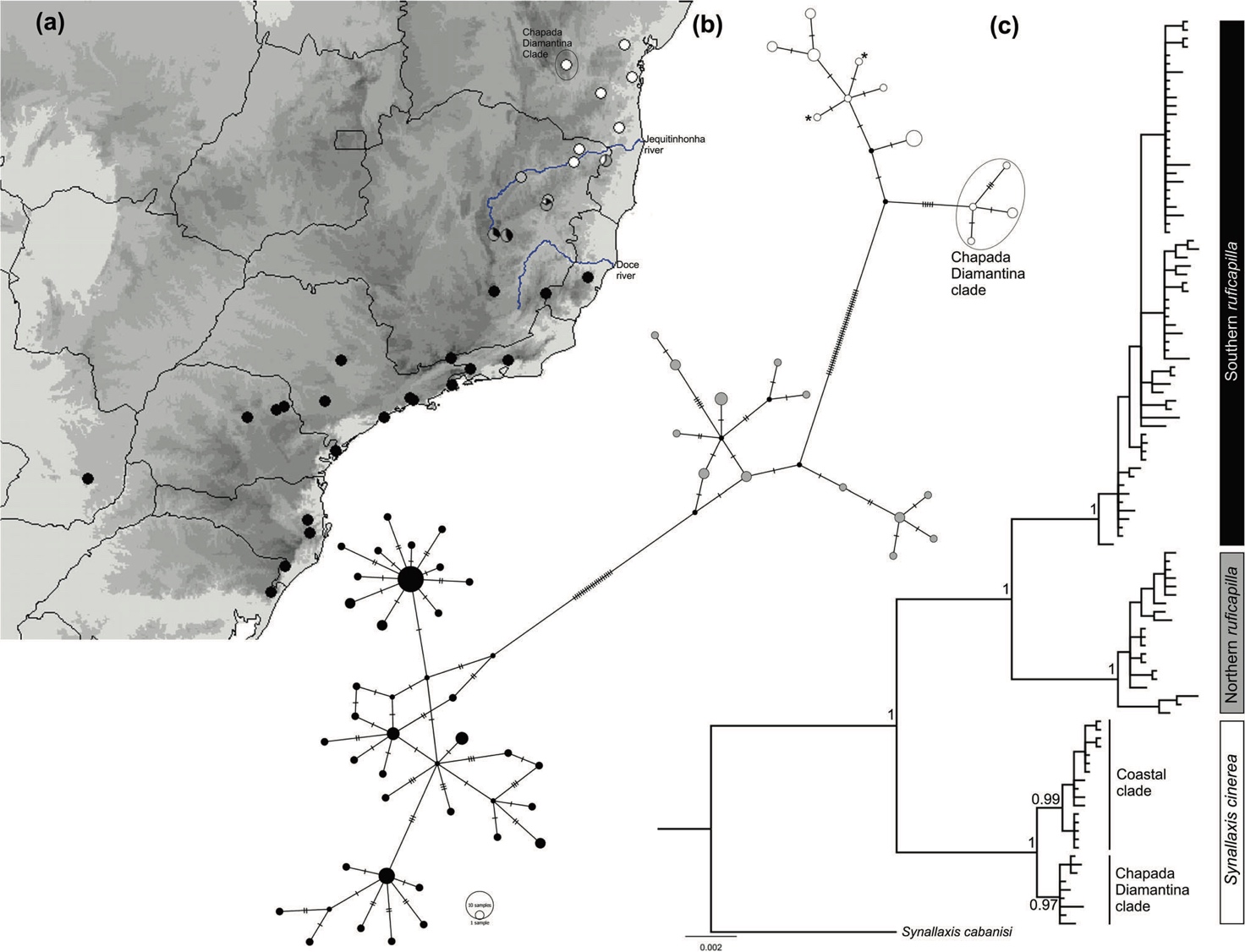

Fig 1 from Batalha-Filho et al. 2019

Fig 2 from

Batalha-Filho et al. 2019.”

Additional comments from Stiles: “I am

willing to change my vote to NO, based on the commentaries by Josh and Nacho.”

Comments from Areta: “NO.

Despite a lengthy email exchange, the lead and corresponding authors were

unable to provide a raw data spreadsheet. So, as things currently stand, I

cannot differentiate the different possible scenarios, and thus I prefer to

wait for more and better evidence before changing our current taxonomy.”