Proposal (1032) to South

American Classification Committee

Change current taxonomy

of the genus Gygis: A) recognize subfamilies Gyginae and Anoinae within

Laridae; B) split White Tern (Gygis alba) into three species; and C)

revise English names for Gyginae

FOREWORD

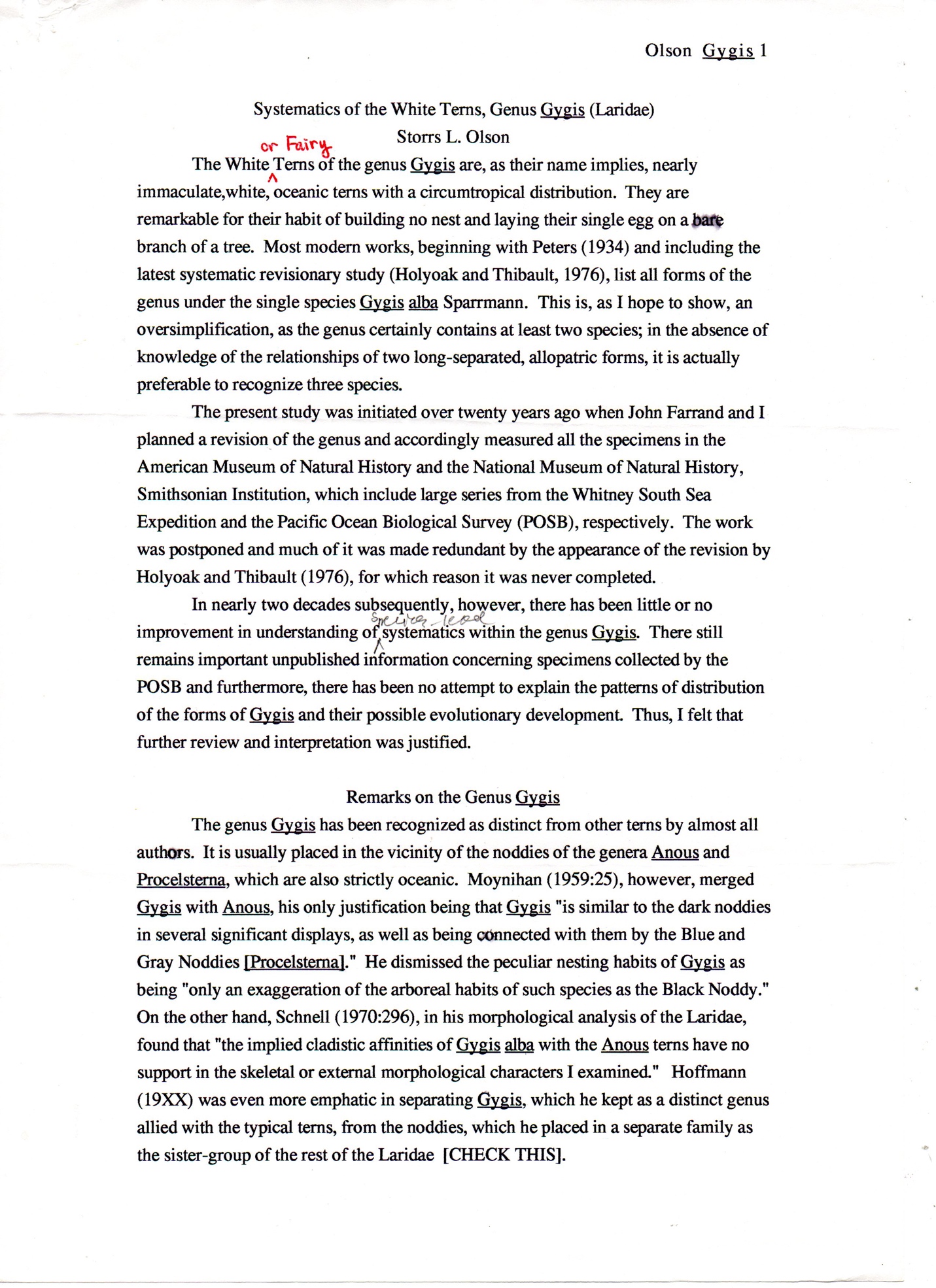

Pratt's

(2020) paper, which is the primary basis for this proposal, was to have been coauthored

by Storrs L. Olson but the Covid-19 pandemic and resultant lockdown of the

research divisions of the Smithsonian Institution prevented him from retrieving

his notes on Gygis in time, and Pratt's paper was published only with

some information cited as pers. comm. from Olson. Not long afterwards, Olson

unfortunately fell ill and died (not from Covid). In June 2022, with the

invitation and assistance of Helen James, Pratt located Olson's Gygis

file in the Bird Division of the USNM, and took

custody of it at the institution's request. Surprisingly (Olson had not

mentioned it), the folder contained not only the expected data forms and

correspondence, but also a nearly finished 6-page typed draft, prepared in

April 1994, of a paper about species limits in Gygis. In an accompanying letter

to the late Claudia Wilds, Olson stated his intention to submit the paper as

soon as possible but for unknown reasons he never did so. The manuscript includes

handwritten notations in red made by Wilds along with a letter from her with

additional relevant comments. Copies of the MS plus Wilds's letter are attached

herewith (following Lit. Cit., pp. 12-18). Combined, they provide two

pre-molecular "voices from the grave" in support of the taxonomy

proposed herein. Although we cite Olson's (MS) findings where they supplement other

results, we urge the committee to read his entire original manuscript for the

insights it contains, including a summary of Olson's detailed analysis of

specimens in the American Museum of Natural History (from the Whitney South Sea

Expedition) and the Smithsonian Institution (from the Pacific Ocean Biological

Survey, POSB). The actual handwritten measurements that accompanied the Olson MS

and can be supplied on request. Olson was quite prescient of genetic research

that later confirmed his suggestions regarding the classification of Gygis

and Anous.

This

proposal consists of three parts, which can be voted on separately.

A)

Recognize subfamilies Anoinae and Gyginae within the family Laridae.

Background: The SACC currently

classifies Gygis and Anous among the terns (Laridae: Sterninae).

New

information:

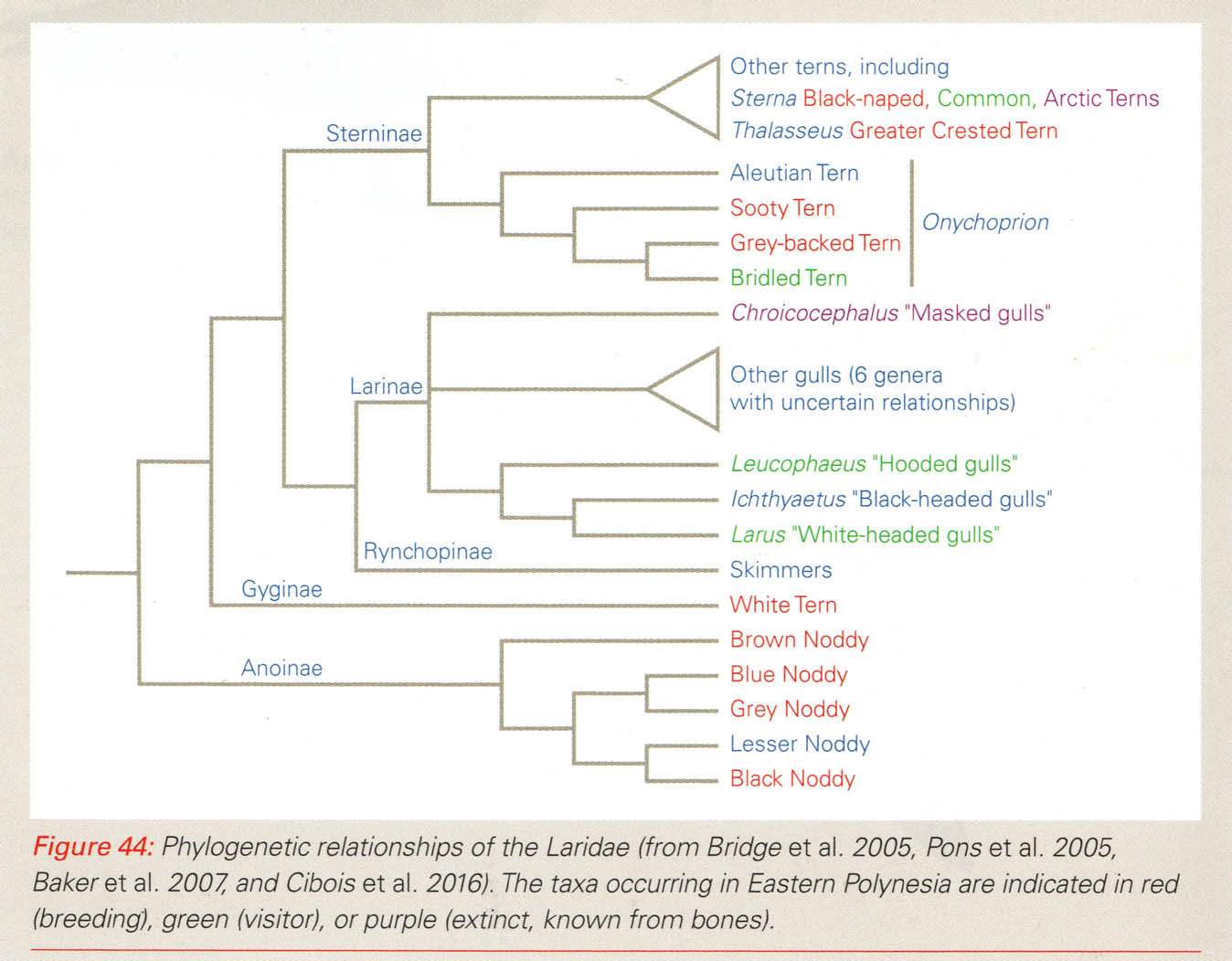

Although fine branching details may differ, nearly all recent studies (Bridge

et al. 2005, Pons et al. 2005, Baker et al. 2007, Cracraft 2013, Thibault and

Cibois 2017, Černý and Natale 2022) and world checklists (HBW and Birdlife

International 2022, Boyd 2024) recognize Gyginae and Anoinae as co-equal

subfamilies with Larinae, and Sterninae within Laridae. (These authors also include

Rhynchopinae which SACC regards as a separate family.) Olson (MS) anticipated

this arrangement based on osteological and other morphological criteria.

Thibault and Cibois (2017:246) produced a unified phylogeny based on four

studies that produced identical basal branching patterns (a remarkable fact in

and of itself):

Černý

and Natale (2022) differed in showing Rhynchopinae in the most basal position

and Gyginae and Anoinae as sister groups (but with a divergence well before

that of the other subfamilies) and regard the five lineages as of equal

subfamilial rank. Gill et al. (2024) place the noddies and Gygis in a

basal position among typical terns but do not designate subfamilies. Boyd (2024)

uniquely recognized Sternidae (terns including Sterninae and Gyginae) and

Laridae (gulls including Larinae and Anoinae). Clearly, Howell and Zufelt's

(2019) and Harrison et al.'s (2021) use of the term "white noddies"

for Gygis is no longer acceptable.

Recommendation:

We

recommend that the SACC bring its classification into line with the majority of

those that recognize subfamilies by recognizing Anoinae and Gyginae as basal to

other subfamilies within Laridae.

Note

from Remsen:

If this part of the proposal passes, then the Rynchopidae must also be ranked

as a subfamily.

B)

Split Gygis alba into three species.

Background: American

Ornithologists' Union (1998 and Supplements) lists the genus Gygis as

comprising a single species G. alba with three subspecies groups, alba,

candida, and microrhyncha (extralimital for SACC). The

differences of the form leucopes (Holyoak and Thibault 1974) were considered

"minor" by Thibault and Cibois (2017), and they disregarded it, as do

we. Subsequent authors have variously recognized one (Harrison et al. 2021),

two (Pratt et al. 1987, del Hoyo and Collar 2014, Boyd 2024) or three (Olson

2005, Steadman 2006, Howell and Zufelt 2019, Pratt 2020, HBW and Birdlife

International 2022) biological species within Gygis. Yeung et al. (2009),

supplemented by Thibault and Cibois (2017), used mitochondrial genes to

conclude that only one undifferentiated taxon of Gygis occurs in the

Pacific Ocean, but Thomas et al. (2004) and Černý and Natale (2022) split G.

microrhyncha (neither study included alba). For a discussion of

discordance among molecular findings and between molecular and phenotypic data see

Pratt (2020).

New

Information:

ARCHAEOLOGY.

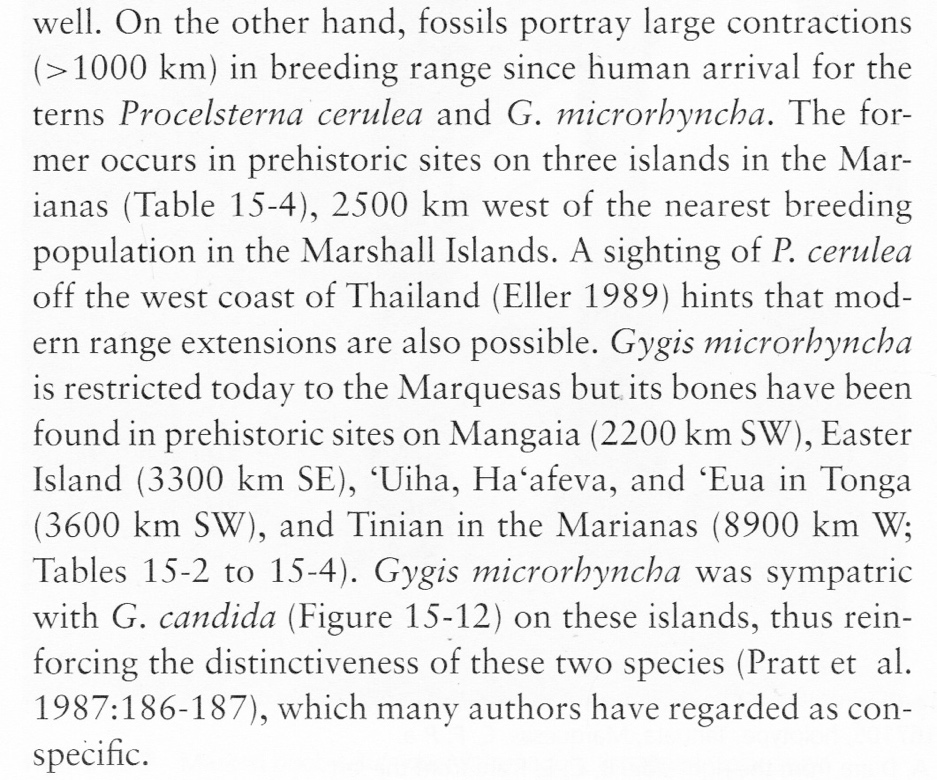

Subfossil bones reveal that candida and microrhyncha were

sympatric in prehuman times over a ca. 9,000 km swath of the tropical Pacific

from Tinian in the Marianas to Easter Island. Here is the relevant text from

Steadman (2006:400):

This

alone establishes that these two taxa are separate species under the BSC. Thibault and Cibois (2017) suggested that

Steadman (2006) merely divided a continuum of size at some arbitrary point and

called larger specimens candida and smaller ones microrhyncha,

but that idea either overlooks or ignores qualitative differences of which

Steadman (2006) was clearly aware (Pratt 2020).

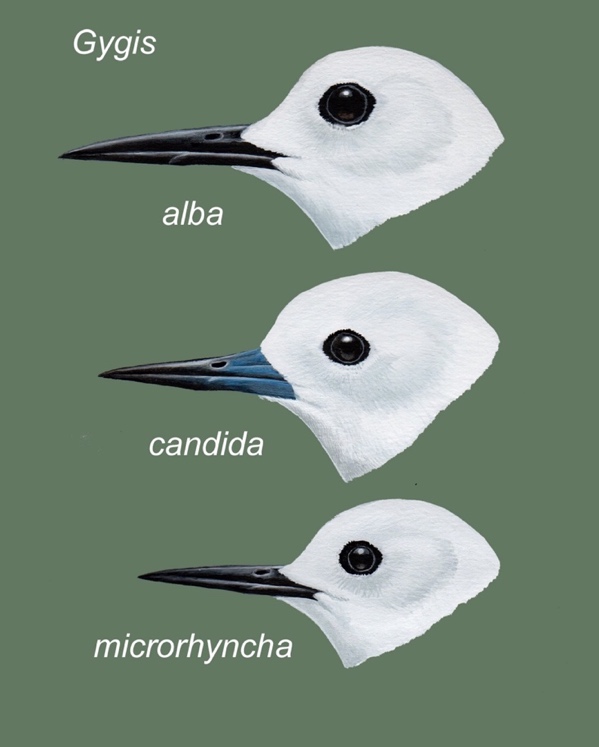

MORPHOLOGY

AND COLORATION. The genus Gygis exhibits two strikingly different bill shapes,

one resembling that of other small terns (Sterninae) and the other quite

distinctive. Those of alba and microrhyncha are of the former

type, with the loral feathering extending forward toward the nostrils and the

malar feathering also extending forward into the mandible. The bill of alba

is somewhat thicker at the base and the gonydeal angle somewhat more anterior,

but otherwise the two are similar in shape and both are black throughout. The

bill of alba is significantly larger than that of aptly named microrhyncha.

The bill of the more familiar candida is intermediate in size and

dagger-like or long triangular, with a basal insertion that forms a nearly

straight line in profile. The anterior half is black but from the nostrils and

gonydeal angle back, it is deep cobalt blue. These different bill shapes

produce somewhat different head profiles. A picture being worth 10K words, here

is Pratt's (2020) illustration:

The

three forms of Gygis also differ in tail shape, with candida

showing a more deeply forked tail than microrhyncha and alba

intermediate (although closer to candida); and in the amount of

pigmentation in the shafts of the outer primaries, with distinctly black shafts

in candida but alba and microrhyncha showing less

pigmentation that ranges from white to golden brown and occasionally to black

(Wilds, in litt., pers. obs.).

VOCALIZATIONS.

Pratt (2020) made the first detailed study of vocalizations, archived in Macaulay

Library (ML;www.macaulaylibrary.org) and Xeno-canto (XC; www.xeno-canto.org), in

Gygis. The voice of candida is well documented, but recordings of

microrhyncha and alba are scarce and therefore must be used with

caution in making comparisons. Nevertheless, Pratt (2020:204) concluded that

each taxon in the genus has "a unique vocal repertoire easily

distinguishable from the other two". The vocalizations of alba are

particularly distinctive in being "strikingly lower pitched" than those of candida

or microrhyncha with few obvious homologies. One vocalization (XC431354)

appears to have no equivalent in either Pacific form. Although further research

on vocalizations of alba and microrhyncha is needed, current knowledge

suggests that vocal differences may well serve as isolating mechanisms among

three species.

STATUS

OF ALBA: The question of whether alba is a third species or

conspecific with microrhyncha was addressed by Olson (MS), who concluded

that the striking difference in size warranted species status. Pratt's (2020)

observations on vocalizations add further evidence that alba is

distinct. To date, no published genetic studies have included alba, but

unpublished preliminary data from N. Yeung (pers. comm.) suggest that alba is

genetically "very different". Obviously, this is fertile ground for

further research.

Recommendation: Split Gygis alba

into three species: G. alba (South Atlantic islands of Ascension, St. Helena, Fernando de Noronha,

and Trindade); G. candida (tropical Indian and Pacific oceans);

and G. microrhyncha (extralimital in Marquesas Islands south of

Hatutaa, with historical occurrence in Kiribati). With this split, add G.

candida to the South American Checklist.

C)

Revise English names within Gyginae:

Background: As a single iconic

species, G. alba has long been, and continues to be, called "fairy

tern" by the lay public (Wilds, in litt.). That name has now been

restricted by various "official" lists, including AOS, to Sternula

nereis of southern Australia and New Zealand, but its use persists elsewhere

for G. alba especially where the birds are conspicuous to large

English-speaking populations. Even among those who use "White Tern",

that name is often, perhaps usually, followed by some phrase such as "also

known as fairy tern." In Honolulu, where the bird is an official city

icon, the hybrid name "White Fairy Tern" has gained popularity as an

informal way to get around the problem (see Pratt 2020 for references,

especially Floyd 2019). Note that if we recognize 3 species of Gygis,

the unmodified name White Tern should be reserved for the original unsplit

species.

New

information:

All

other Larid subfamilies, Anoinae (noddies), Larinae (gulls), Rhynchopinae

(skimmers), and Sterninae (terns), have single-word group-names with their own

separate listings in indexes. Use of "white terns" as a group-name,

even if hyphenated, in our opinion fails to distinguish the Gyginae adequately

from the Sterninae and will surely obfuscate. Pratt (2020) proposed the novel

single word group-name "fairyterns", for the

Gyginae to emphasize that they are NOT terns in the traditional sense, and

leaving Fairy Tern (sometimes Austral Fairy Tern) for Sternula nereis.

Note that "fairytern" has a subtly different pronunciation from

"fairy tern". We are aware that this committee would ordinarily

prefer the construct "fairy-tern" as did Pratt et al. (1987), but

experience has taught us that indexers can be stubborn and idiosyncratic in

such matters and may index the three species of Gygis among the true

terns, hyphen notwithstanding. Thus "fairy-tern" is invested with the

same problems as "white-tern". " Fairytern" allows no

indexing option. This exception for Gygis is only necessary if the

subfamily Gyginae is recognized (Part A). As Pratt (2020:206) observed, using

"fairytern" will "allow non-professionals to maintain a beloved

and widely used name without being scolded by pedants." Pratt (2020)

proposed the English names Common Fairytern (G. candida), Little

Fairytern (G. microrhyncha), and Atlantic Fairytern (G. alba) for

the three species. We acknowledge that "Common" as an adjective in

English bird names has met with some recent disfavor, but we believe it is

particularly appropriate in this case because it is the fairytern most people

will see, being vastly more widespread and common than the other two species,

and the name has a long history of use in the Pacific (at least since Pratt et

al. 1987). AOU (1998) uses "Pacific" for candida but that is

geographically too restrictive. Howell and Zufelt (2019) suggested the epithet

Indo-Pacific for G. candida, but, while accurate, it is something of a

mouthful and unfamiliar to most potential users.

Recommendation: Assuming Part A is

approved, adopt the English single word group-name "fairyterns" for the

Gyginae, and the English names Atlantic Fairytern (G. alba), Common

Fairytern (G. candida), and Little Fairytern (G. microrhyncha)

for the subfamily's three species.

Literature

Cited:

American

Ornithologists' Union. 1998. Check-list of North American birds. 7th. Edition American

Ornithologists' Union, Washington, DC.

Baker, A. J., S. L.

Pereira, and T. A. Paton. 2007. Phylogenetic relationships and divergence times

of Charadriiformes genera: multigene evidence for the Cretaceous origin of at

least 14 clades of shorebirds. Biology Letters 3: 205-210.

Boyd, J. H., III. 2024.

Taxonomy in flux: Version 3.49, June 19, 2024 (February 21, 2024). Accessed 4

August 2024.

Bridge, E. S., A. W.

Jones, and A. J. Baker. 2005. A phylogenetic framework for the terns (Sternini)

inferred from mtDNA sequences: implications for taxonomy and plumage coloration.

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 35:459-469.

Černý, D., and R.

Natale. 2022. Comprehensive taxon sampling and vetted fossils help clarify the time

tree for shorebirds (Aves, Charadriiformes). Molecular Phylogenetics and

Evolution 177: 107620.

Cracraft, J., 2013.

Avian higher-level relationships and classification: Nonpasseriforms. In: Dickinson,

E.C., Remsen, J.V. (Eds.), The Howard and Moore Complete Checklist of the Birds

of the World, Volume 1: Non-passerines (4th edition). Aves Press, Eastbourne,

UK, pp. xxi– xliii.

Del Hoyo, J., and N. J.

Collar. 2014. HBW and BirdLife International checklist of the birds of the world.

Vol. 1: Non-passerines. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Gill F., D. Donsker

& P. Rasmussen (Eds). 2024. IOC World Bird List (v14.1). doi:

10.14344/IOC.ML.14.1.

Floyd, T. 2019. How to

know the birds: no. 20, Alien fairies in the big city. https://blog.aba.org/2019/11/how-to-know-the-birds-no-20-alien

fairies-in-the-big-city.html. American Birding Association, Delaware City.

Harrison, P., M.

Perrow, and H. Larsson. 2021. Seabirds: The new identification guide. Lynx Edicions,

Barcelona.

HBW and BirdLife

International. 2022. Handbook of the Birds of the World and BirdLife International

digital checklist of the birds of the world. Version 7. Available at: http://datazone.birdlife.org/userfiles/file/Species/Taxonomy/HBW

- BirdLife_Checklist_v7_Dec22.zip

Holyoak, D. T., and J.

C. Thibault. 1976. La variation geographique de Gygis alba. Alauda 44:457-473.

Howell, S. N. G., and

K. Zufelt. 2019. Oceanic Birds of the World. Princeton University Press, Princeton

and Oxford.

Pons, J.-M., A.

Hassanin, and P.-A. Crochet. 2005. Phylogenetic relationships within the

Laridae (Charadriiformes: Aves) inferred from mitochondrial markers. Molecular

Phylogenetics and Evolution 37:686-699.

Pratt, H. D. 2020.

Species limits and English names in the genus Gygis (Laridae). Bulletin

of the British Ornithologists' Club 140:195-208.

Pratt, H. D., P. L.

Bruner, and D. G. Berrett. 1987. A Field Guide to the Birds of Hawaii and the Tropical

Pacific. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Steadman, D. W. 2006.

Extinction and Biogeography of Tropical Pacific birds. University of Chicago

Press, Chicago.

Thibault, J.-C., and A.

Cibois. 2017. Birds of Eastern Polynesia: a Biogeographic Atlas. Lynx Edicions,

Barcelona.

Yeung, N. W., D. B.

Carlon, and S. Conant. 2009. Testing subspecies hypotheses with molecular markers

and morphometrics in the Pacific White Tern complex. Biological Journal of the Linnean

Society 98:586-595.

Storrs

Olson’s original MS with comments from Claudia Wilds:

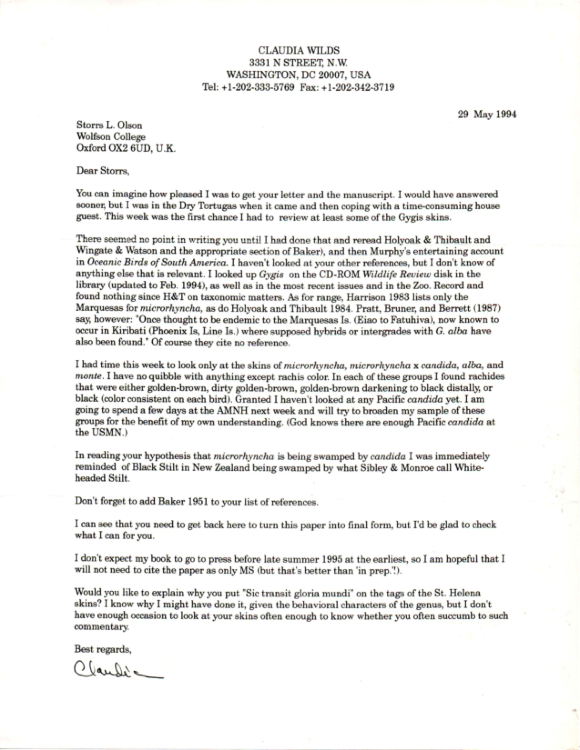

Letter

from Claudia Wilds to Storrs Olson:

H. Douglas Pratt and Eric

A. VanderWerf (and Storrs L. Olson, posthumous contributor)

September 2024

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Vote tracking chart: https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart968-1043.htm

Comments from Stiles: “B. Gygis:

Yes to recognizing the three species mentioned – and I found both Olson’s and Steadman’s comments

exceptionally interesting.”

Comments

from David Donsker (who has Bonaccorso vote on C):

“C. NO. Although

I am very sympathetic with Doug’s efforts to invent a new English name for these

ethereal species which incorporates the delightful “Fairy Tern” in its

construction, the compound word “fairytern”, in my

opinion, smacks as an artificial and unnecessary neologism.

“The

Australians have justifiably strong claims to use “Fairy Tern” for Sternula

nereis, so it is best to remove that name from use for Gygis species.

“White

Tern” is now firmly established for Gygis, and perhaps though not as

evocative nor as romantic as a name that includes “fairy”, is perfectly

descriptive of these essentially pure white species.

“I am not

as concerned about the “indexing issues” as Doug writes.

“So, I

vote NO to adopting “fairytern” for this group.

Instead, I would prefer “white tern” or, if we must, “white-tern”. I would follow Doug’s recommended adjectives

per his discussion (but I would certainly accept “Pacific” or “Indo-Pacific”

White Tern for G. candida, if

either of these two names were preferred over “Common” by the majority):

Gygis alba Atlantic White Tern

(White-Tern)

Gygis candida Common White Tern

(White-Tern)

Gygis microrhyncha Little

White Tern (White-Tern).”

Comments

from Remsen:

“A. YES. I’m in favor of recognizing deep

splits within families by applying taxon ranks such as subfamilies and tribes.

“B. YES to three species, which all

differ from one another by a suite of phenotypic characters, including

voice. I think burden-of-proof falls on

treating them as a single species, especially given that only minor phenotypic

differences are used to delimit several species of terns and gulls. For example, Least Tern (Sternula

antillarum) and Little Tern (S. albifrons) are arguably more

similar, phenotypically, than are the three Gygis taxa.

“C. NO.

“Fairy Tern” is too well-established for S. nereis, which is too

bad because as noted in the proposal, I think it is more apt for Gygis. Further, one word ‘Fairytern’

is a fairly unusual construction, although we do already have the single word

‘fairytale’, which is a parallel construction.

This dislike of Fairytern” is simply a matter

of taste on my part (and if it were up to me, it would be ‘fairy-tale’ just

because it think “ryt” is an ugly combination). So, I agree with David and think we should go

with Something White-Tern for each one, but dredging

the depths for a replacement for ‘Common.’”

Comments from Areta:

“A. YES.

“B. I vote NO to any split. The

fossil evidence is not so straightforward to interpret: variation in size could

mean many things, especially when dealing with fossils, which themselves could

have been from slightly different times (I find the argument of strict sympatry/syntopy

without interbreeding based on fossils very hard to buy) or could have

represented former variation (and looking at the PCA in Thibault & Cibois

2017, a diagnosability/effect size test is called for, as several ‘microrhynchus’

bridge the gap). I am not happy with considering the fossil data as evidence of

the ‘gold standard’ of syntopy without hybridization.

“The fact that Pratt (2020) himself

finds evidence of "genetic swamping", and that candida and microrhynchus

seem to hybridize extensively in Hatutaa is in agreement with considering the forms here as a single

species. Based on the available evidence, it seems that just not enough time

has passed to grant the somewhat distinctive microrhynchus enough time

to speciate and stay separate from candida.

“As for the split of alba from candida/microrhynchus,

it might be correct and to me more easily digestible than the split of candida from

microrhynchus, but where are the data?

“The case is interesting for a full

genomic study, given the morphological features that Pratt points out. I prefer

not to discard the mtDNA similarity as some kind of aberration or simply a

product of historical hybridization events, but I would rather take the

opposite view: someone must show the extent of genomic differentiation between

the hybridising taxa in order to have a firm grasp of

what is going on. This is especially relevant in light of the wild variation in

size of birds from the Atlantic islands (Fernando de Noronha, Ascension,

Trindade, St. Helena) reported by Olson in his manuscript (although the

measurements are not shown).

“Vocalizations need to be properly analysed. Until then, the vocal evidence (pitch differences

only, perhaps, which could be simply a biomechanical byproduct of size) seems

inconclusive.

“I see with kind eyes the 3-way

split, but I think that there is not enough evidence to fully support this

treatment, and there are many populations that seem to be telling different

stories here (e.g., leucopes seems quite

distinctive!). If any different population is called a species, it seems that

we should have many more Gygis species, not just 3. Meanwhile, although

the single-species is not very appealing, the 3-species option is also

problematic.”

“C. NO. I prefer Atlantic White Tern G. alba,

Little White Tern G. microrhyncha, and Blue-billed White Tern G.

candida(note however that I do not support the splits, as I voted NO on B).”

Comments from Rasmussen (voting for

Robbins on C.):

“C. I'm not sold on fairytern, given the potential for confusion with THE Fairy

Tern (or Australian Fairy Tern, as Clements has it). Really Gygis are

more fairy-like than Sternula nereis in appearance, though they don't

sound like anyone's idea of what a fairy should sound like. White tern is

awfully blah for these ethereal creatures, but it is deeply ingrained. One

option might be to use Gygis as a group common name, but then, does anyone

really know how it should be pronounced (without googling it)? Combined, there

are four different ways to pronounce the gs... So,

assuming SACC splits them (as WGAC/AviList has voted to do), I'm voting for

Atlantic White-Tern, Little White-Tern, and Indo-Pacific White-Tern. These are

the Howell/Zufelt names except using Tern instead of

the misleading Noddy.”

Comments from Bonaccorso: “A. YES.

The “summary phylogeny” shows deep splits that may help understand differences

among taxa in these different lineages when ranked as subfamilies.”

Comments from Robbins:

“A: YES to recognition of the

subfamilies.

“B: YES. Based on morphology and

what current vocal data indicate coupled with what Steadman determined from

subfossil bones (very cool!) it appears that three species of Gygis

should be recognized.”

Comments from Lane:

“A) YES.

“B) YES. I think Pratt has made a strong case for recognition of

three species here.

“C) NO to the suggested name “Fairytern”

as per comments from other committee members above. As lovely as it would be to

use “Fairy Tern” or some similar construction for Gygis, I think we’re

best off avoiding the inevitable confusion by adopting “White Tern” or

“White-Tern.” Using “Atlantic,” “Indo-Pacific,” and “Little” would probably be

best.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“

“A) YES. These deep splits should be recognized at

equal levels across the family.

“B) “YES to the

3-species treatment. As stated in the

Proposal, the fossil evidence presented in Steadman (2006) showing prehistoric

sympatry of candida and microrhyncha provides an argument for

treating those two taxa as separate under the BSC, and the other morphological

distinctions, particularly those of bill shape and coloration are enough to

convince me that all 3 should be treated as separate species, and that’s not

even taking into account the vocal differences suggested by Pratt (2020). Also, going back to morphological

distinctions, along with the bill differences between candida and alba/microrhyncha,

the included illustration from Pratt (2020) suggests that alba has eyes

that are not only larger in actual size, but also relatively larger, and

differently placed, compared to those of the other two taxa. If this is consistent as illustrated, it

suggests some ecological distinction that could be every bit as significant as

are the bill shape/structure distinctions.

And, going back to the bill differences, I would have to think that the

contrasting, cobalt blue bill base of candida, versus the

entirely black bills of microrhyncha and alba would also have

some significance to mate choice & conspecific recognition in a group in

which neither plumage nor other bare parts differ in color. I think Van’s point about the minor

phenotypic differences used to delimit several species of terns and gulls is

also pertinent to this discussion and places the burden of proof firmly onto

those who would advocate for maintaining a single species.

“C) NO to the suggested

group name of “Fairyterns”, primarily for the

possible confusion it could engender with Sternula nereis. I must say that I don’t share the same

negative reaction to the construction of the name as others – after all, we

have Fairywrens, which I haven’t heard any complaints about. So, I would go with White Tern (with or

without the hyphen, although I suspect our guidelines might require it) as the

group name and then, Atlantic (alba), Blue-billed (1st

choice, with Indo-Pacific as my 2nd choice) (candida), and

Little (microrhyncha) as the modifiers.

Yes, I know, only the base of the bill is blue in candida, but it

is an obvious field mark in a group of 3 otherwise similar taxa, and it rolls

off the tongue more readily than Indo-Pacific (and “Common” is just really

objectionable to me).”

Comments

from Mark Pearman (voting for Claramunt on C):

“C.

NO. Like others, I agree that “Fairytern” is a

confusing group name which should not be used. As for vernacular names, I agree

with using Atlantic White Tern G. alba (preferably without a

hyphen) and Little White Tern G. microrhyncha. I am also fully

sold on Kevin Zimmer’s Blue-billed White Tern G. candida which I

think is a great solution. When using “common” in a vernacular name, what we

usually mean to say or imply is “widespread”, but we just can’t step over the

line and call a bird Widespread Suchandsuch.

Kevin’s solution points to a unique feature of candida within the genus Gygis

and that is all that is needed, assuming that the split goes through.”

Comments

from Claramunt:

“A. YES. Subfamily

ranks will highlight the basal divergence of Gygis and Anous.

And, to be consistent, we need to bring in skimmers as a subfamily too, as I

proposed a while ago (Proposal 810).

“B. NO. There are

definitely very interesting morphological variations in body size, bill anatomy,

and tail morphology (and voice), but a more explicit quantitative analysis of

geographic variation is needed, in my opinion. Those who have analyzed

variation in detail (Storrs, Doug, and the cited papers) have found intergrades

between candida and microrhyncha(See another example of a bill

morphology intermediate between candida and microrhyncha from Hatutu: https://ebird.org/checklist/S64822306). And the genetic data

so far suggest a single, well-mixed population across the Pacific. The

morphological variation alone does suggest that more than one species is

involved, but the evidence for the split is still unclear to me, in the face of

the evidence of intergradation. Both genetics and morphology indicate gene flow

and intergradation. The case for separating alba from the other may be

stronger but a quantitative analysis is needed.”

Comments from Stiles:

“A. treat

Gyginae as a subfamily of Laridae (ditto Anouinae):

YES. As Van noted, phylogenetic consistency would also favor demoting

Rynchopidae to a subfamily (a separate proposal?).

“B.

recognize alba, candida and microrhyncha as species: YES -

morphology, vocalizations and distribution all fit -but the sticking point

could be the existence of apparent hybrids between candida and microrhyncha

some islands. As far as I can determine, these represent a small subset of the

many islands where the two both occur, acting as distinct species (am I correct?)

“C. NO. The

group name "Fairyterns" doesn´t convince

me: it seems too polysyllabic with the accent falling on "fairy", not

"terns" I prefer White Terns (best without hyphenation) for the

group; the species epithets suggested (Atlantic, Indo-Paific,

and Little) are OK by me.”

Comments from Kimball Garrett (voting for

Del-Rio):

“A. YES to the

recognition of subfamilies Anoinae, Gyginae, and Rynchopinae.

“B. YES to the

three-way split of alba, candida, and microrhyncha. Note,

however, that the NACC is adjudicating this issue at the same time, and I hope

both committees reach the same decision.

“C. NO to the use of “fairytern” as a group name. I do like “Fairy Tern” as a

group name, but its use for an Australasian species of Sternula

essentially makes it unavailable, and I doubt we are open to lobbying

Australian ornithologists to change that name to something like “Wee

Tern.” Therefore, I would go with “White

Tern” or “White-Tern” for the group name. As for modifiers for the three

proposed species, I think Little White Tern for microrhyncha and

Atlantic White Tern for alba make sense. As for candida, I am

fine with “Indo-Pacific White Tern,” and I note that “Indo-Pacific” is a very

common modifier in English names of non-avian marine species (though,

surprisingly, not used for any species of bird). Having said that, this is a

case where I would also be happy with “Common” as a modifier, since candida is

overwhelmingly the most common Gygis species, both in absolute numbers

(perhaps two orders of magnitude more numerous than the other two species) and

in breadth of geographic range.”

Comments from A. W. Diamond (voting

for Jaramillo):

“I am not a systematist, nor a

geneticist, but have extensive experience of Gygis in the Indian Ocean

(which seems to be somewhat neglected by most in this field). I also have

strong opinions on the English nomenclature of this fascinating bird! I have

read through most of what you sent and offer the following response:

A: There

seems to be an impressive amount of genetic evidence supporting this case, so I

am happy to answer YES.

B: I had been

unaware of Steadman's evidence for coexistence of candida and microrhyncha

in the Pacific prior to human colonisation; this

seems to clinch the case for responding YES.

C: This is

where things get difficult! I see that most respondents prefer some version of

White Tern because Sternula nereis has co-opted Fairy Tern, but

throughout the Indian Ocean (and I think

in Hawaii too?) the common name among both local people and visitors unaware of

the existence of S. nereis is Fairy Tern, and since they are so numerous

there, more weight should be given to local usage and acceptance. The arcane

'rules' of English bird nomenclature are irrelevant to most people who live

among the birds. Also 'White Tern' is as bland and unappealing as 'Black Tern'

- surely we can do better?

“So here again I vote YES for

some version of Fairytern though 'Common' should

always be avoided and I would go for Indopacific by

preference.”