Proposal (1033) to South

American Classification Committee

Treat Basileuterus

delattrii as (A) a separate species from Rufous-capped Warbler B.

rufifrons, and (B) having the English name Chestnut-capped Warbler

Note

from Remsen: This

is a proposal submitted to and passed by NACC; the original is relayed here as

is, modified slightly for SACC. Treat

this proposal in two parts: A. Species limits.

B. English name.

Effect

on SACC classification: Approval of this

proposal would change the species name and English name of the species we

currently call, Basileuterus rufifrons, Rufous-capped Warbler, to Basileuterus

delattrii, Chestnut-capped Warbler.

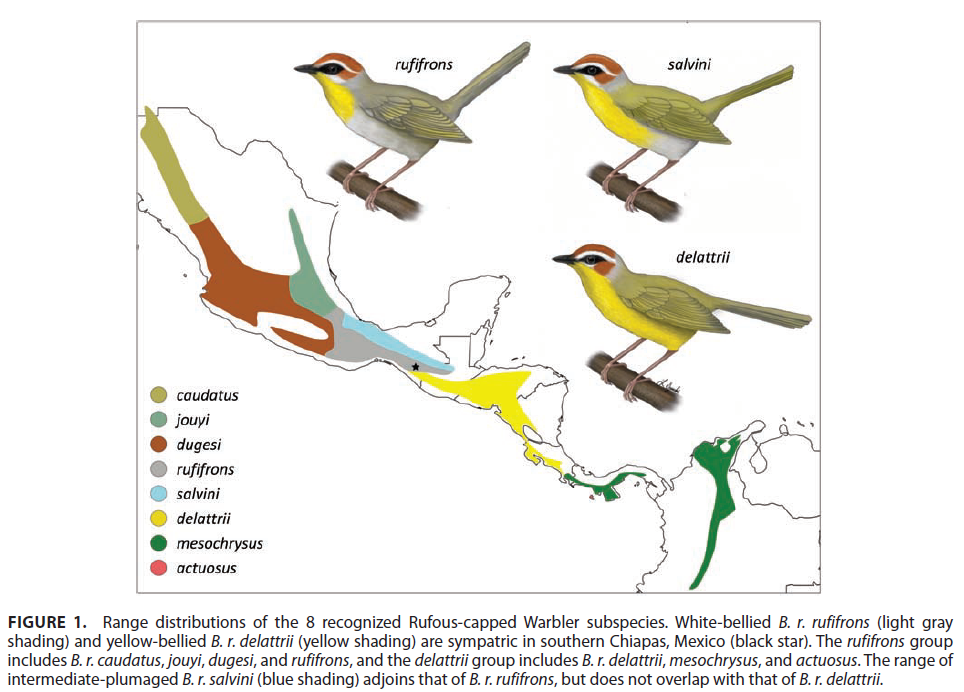

Background:

Basileuterus rufifrons is currently considered

to consist of eight subspecies distributed primarily in Mexico and Central America, but also

including the southwestern US and northern South America (see map below;

subspecies actuosus, difficult to locate on the map, occurs on Isla

Coiba, off the Pacific coast of Panama).

Subspecies are generally considered to form two

groups: the rufifrons group (including caudatus, jouyi, dugesi,

and rufifrons, we will hereafter refer to this group as simply “rufifrons”

unless we specify otherwise), and the delattrii group(consisting of delattrii,

mesochrysus, and actuosus, we will hereafter refer to this group

simply as “delattrii”). In addition to plumage differences, these groups

also differ in vocalizations (e.g., Howell and Webb 1995, Demko and Mennill

2019). The eighth subspecies, salvini, is intermediate between the two

groups in some plumage features, most notably the extent of yellow coloration

on the underparts (see depictions above), but it has typically been considered

part of the rufifrons group.

The taxonomic status of rufifrons and delattrii

has long been debated due to the variation in plumage and other characters.

Ridgway (1902) considered the two taxa to be conspecific, but Todd

(1929) not only treated rufifrons and delattrii as separate

species, but placed them in different genera based on differences in relative

wing and tail length (placing rufifrons, including salvini, in

Idiotes). Hellmayr (1935) also treated rufifrons and delattrii

as separate species; he was uncertain about salvini but stated that

it "seems to be a representative form of B. rufifrons."

Eisenmann (1955) treated rufifrons and delattrii as separate

species as well, although he noted that delattrii may be conspecific

with rufifrons.

Monroe (1968) lumped the species based on

intergradation in plumage and morphometrics between rufifrons and delattrii,

stating that rufifrons salvini intergrades with delattrii over a

wide area in eastern Guatemala, El Salvador, and western Honduras. Peters

(1968), in a family account co-authored by Monroe, followed this single-species

treatment, and the AOU (1983, 1998) also treated them as a single species based

on the intergradation noted by Monroe (1968). AOU (1983) considered the species

to consist of two groups (rufifrons and delattrii), whereas AOU

(1998) treated salvini as a third distinct group within the species.

Regardless of taxonomic treatment, the distribution of neither rufifrons

nor salvini was listed as extending south of Guatemala (AOU 1983, 1998),

casting doubt on Monroe’s assertions of intergradation with delattrii in

El Salvador and Honduras (which were nevertheless cited). In their field guide

to birds of Mexico and northern Central America, Howell and Webb (1995)

suggested that rufifrons and delattrii may be separate species,

based on differences in plumage, morphology, and vocalizations, and noted that

they are sympatric in southeastern Chiapas and western Guatemala. Nevertheless,

most current references (IOC, Clements, Bird of the World) treat rufifrons and

delattrii as a single species.

The status of delattrii has thus gone

from species to subspecies of B. rufifrons due to perceived intermediate

specimens from northern Central America. At the extremes of the distribution of

the B. rufifrons complex, DFL can attest to the very different

appearance and voices of the two main groups (rufifrons and delattrii),

but the situation within the Chiapas/Guatemalan portion of the distribution has

been the crux of the issue, with the supposed intermediate taxon salvini

suggesting that these two groups are linked and interbreeding.

New

Information:

Demko

and co-authors, in a series of studies culminating in Demko et al. (2020), have

studied the complex through investigations of various aspects of the biology of

rufifrons and delattrii. The stated purpose of Demko et al.

(2020) was to use voice, morphometrics, and plumage characters to assess

variation within B. rufifrons sensu lato, with a particular focus on

determining whether salvini is intermediate to rufifrons and delattrii,

or more similar to one or the other group. They took measurements of

morphometrics and plumage from more than 400 specimens, focusing on the region

of contact in southern Mexico and Guatemala, and also measured more than 400

songs. One interesting finding, evident in the map above, is that the ranges of

salvini and delattrii do not meet, meaning that salvini is

unlikely to be an intergrade between rufifrons and delattrii.

In

addition to their focus on salvini, Demko et al. also studied song and

other behavior at a site in Chiapas, Mexico, where the rufifrons and delattrii

groups are sympatric.

Morphometric

analyses of wing and tail length showed that only wing length differed

significantly among rufifrons, salvini, and delattrii,

with wings of delattrii significantly longer than those of salvini,

and rufifrons in between. Tail length was similar among groups, and

wing-tail ratio averaged positive for delattrii but negative for salvini

and rufifrons, as previously noted by Todd (1929). In plumage, salvini

was more similar to one or the other group depending on the plumage

character being analyzed.

The

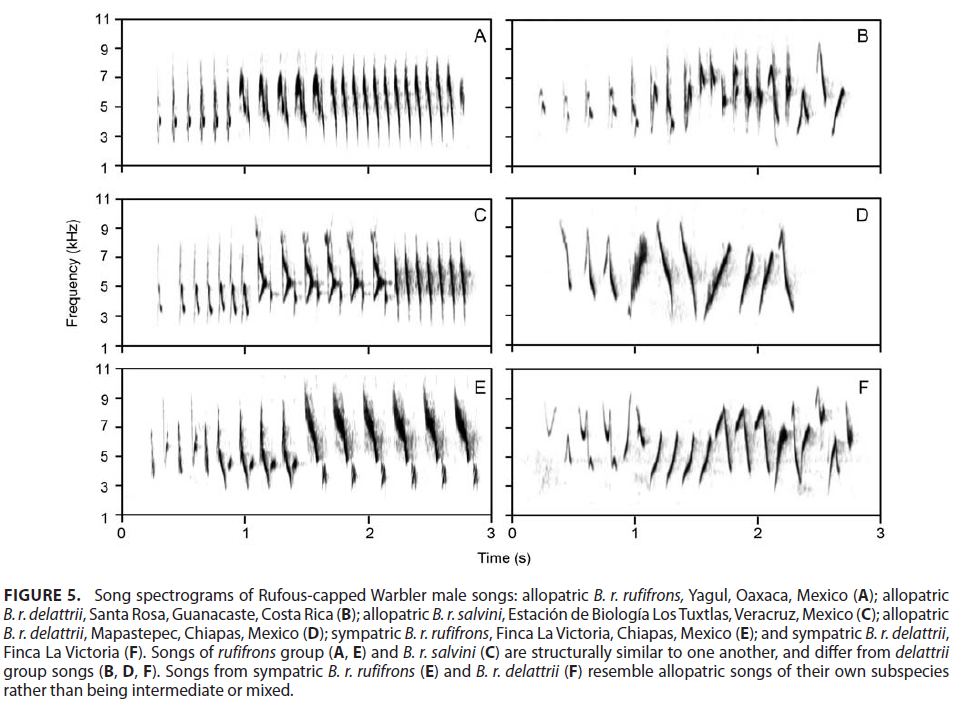

most persuasive and consistent distinctions were found in voice. Here’s Fig. 5

from Demko et al. (2020), showing representative male songs of (A) rufifrons

where allopatric to delattrii, (B, D) delattrii where

allopatric to rufifrons, (C) salvini, and (E) rufifrons

and (F) delattrii where the two groups are sympatric in southern

Chiapas:

Salient

points from the figure are that (1) songs of salvini do not differ

appreciably from those of rufifrons but are very different from those of

delattrii, (2) songs of delattrii appear to be relatively

consistent throughout its range, including in the zone of sympatry with rufifrons,

and (3) songs of rufifrons in the zone of sympatry are very similar to

those of salvini and rufifrons from outside of the zone of

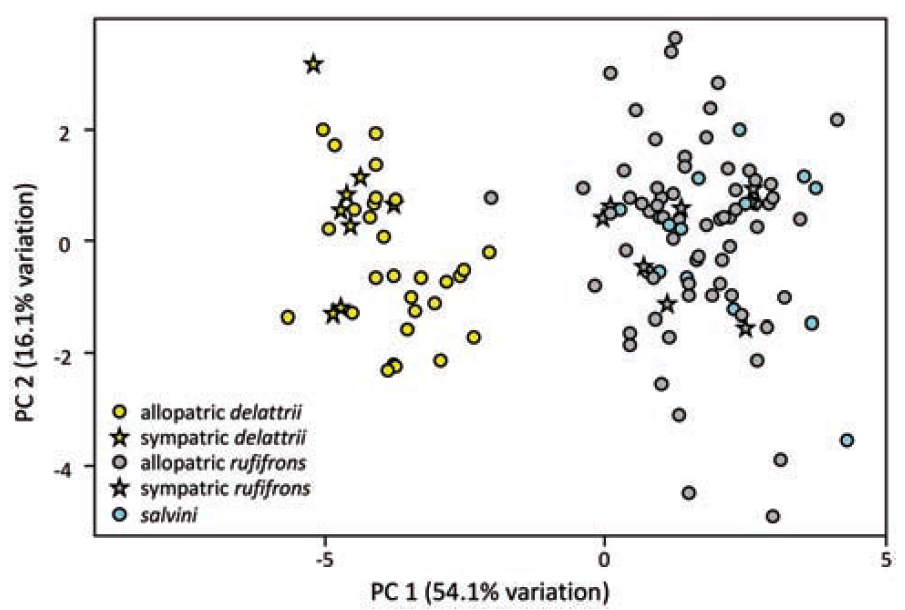

sympatry. These similarities and differences are further illustrated in their

Fig. 6, a PCA of male song, in which songs of salvini and both

allopatric and sympatric rufifrons group together apart from those of

allopatric and sympatric delattrii:

Demko

et al. (2020) concluded that these lines of evidence, particularly the vocal

evidence, are sufficient to treat the two groups rufifrons (including salvini)

and delattrii as separate species.

English

names:

A

vote to recognize two species in this complex will raise the question of

English names for the daughter species. Although rufifrons probably

occupies a larger range than delattrii, the relative range size is

similar enough that the default course of action would be to create new names

for both daughter species. However, NACC's English name guidelines recognize

that range size is a proxy for degree of association of the name with

one daughter or the other, and that relative degrees of association, disruption,

and confusion are actually the key factors in deciding whether to continue to

use a parental name for one of the daughter species in cases of a species

split. The relevant part of our guidelines states:

Strong association of names with particular

daughter species may provide exceptions to the above policy [of providing new

names for both daughter species]. In these situations, a change to the English

name of one daughter species would cause much more disruption than a change to

that of the other daughter species. In these cases, the potential confusion of

retaining the parental name for the daughter species strongly associated with

the name is weighed against the potential disruption of changing the name. Overall,

the goal is to maximize stability and minimize disruption to the extent

possible.

Dating

back to Ridgway (1902), rufifrons has always been known as Rufous-capped

Warbler, sometimes sensu stricto and sometimes sensu lato,

whereas delattrii has been known as Delattre's Warbler (Hellmayr 1935),

Chestnut-capped Warbler (Eisenmann 1955, Hilty and Brown 1986, Howell and Webb

1995), and Rufous-capped Warbler (when considered conspecific, as by Ridgway

1902 and Monroe 1968). Of particular note are the names provided to

intraspecific groups in recent editions of the checklist (AOU 1983, 1998), which

in this case are Rufous-capped Warbler for the rufifrons group and

Chestnut-capped Warbler for the delattrii group. It's a bit of a gray

area for NACC because of the strong association of Rufous-capped with the

northern form (rufifrons sensu stricto) and the retention of

Rufous-capped Warbler as one of the AOU group names, contrasted with the

fact that this name has also sometimes been used for the southern form (when

lumped with rufifrons).

Our

recommendation, following consultation with global references such as the IOC

World Bird List and the Clements Checklist, is that NACC retain Rufous-capped

Warbler as the English name for B. rufifrons and adopt Chestnut-capped

Warbler for B. delattrii. We consider that these English names for these

taxa are well-established in the literature, including Eisenmann (1955) and

Howell and Webb (1995) in addition to their usage as AOU group names, and that

little confusion will result from the past practice of sometimes including the

southern form delattrii within Rufous-capped Warbler. If a new English

name were to be proposed for rufifrons, we would recommend the name

Rusty-capped Warbler, which is close enough to the original name as to be

instantly recognizable, but different enough to distinguish it from the umbrella

name for the parent species.

Recommendation:

We

believe the elegant study of Demko et al. (2020) makes a strong case that rufifrons

and delattrii are best considered valid biological species. We

recommend a YES vote on this split. If this split is supported, then we

recommend the use of Chestnut-capped Warbler as the English name for B.

delattrii and Rufous-capped Warbler for the newly restricted B.

rufifrons.

Literature

cited:

Demko, A.

D., and D. J. Mennill. 2019. Rufous-capped Warblers Basileuterus rufifrons show

seasonal, temporal and annual variation in song use. Ibis 161:481–494.

Demko, A.

D, J. R. Sosa-López, R. K. Simpson, S. M. Doucet, and D. J.

Mennill. 2020. Divergence in plumage, voice, and morphology indicates

speciation in Rufous-capped Warblers (Basileuterus rufifrons). Auk

137:1-20.

Eisenmann,

E. 1955. The Species of Middle American Birds. Transactions of the Linnaean

Society of New York, Vol. 7.

Hellmayr,

C. E. 1935. Birds of the Americas. Field Museum of Natural History Zoological

Series, Vol. 13, Part 8.

Hilty, S.

L., and W. L. Brown. 1986. A guide to the birds of Colombia. Princeton

University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Howell,

S. N. G., and S. Webb. 1995. A guide to the birds of Mexico and northern

Central America. Oxford University Press, New York.

Monroe,

B. L. 1968.

A Distributional Survey of the Birds of Honduras.

Ornithological Monographs No. 7. American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington,

D.C.

Ridgway,

R. 1902. The

birds of North and Middle America. Bulletin of the United States National

Museum No. 50, Part 2.

Todd, W.

E. C. 1929. A revision of the wood-warbler genus Basileuterus and its

allies. Proceedings of the United States National Museum 74 (2752): 1-95.

Terry

Chesser and Daniel F. Lane

September

2024

The

comments of NACC members on this proposal, which passed 8-2, are here:

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Vote tracking chart: https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart968-1043.htm

Comments from Remsen: YES to

both A and B. As outlined in the proposal, the evidence for treatment as

separate species seems solid, based largely on strong vocal differences. Regardless, if rufifrons and delattrii

are sympatric in southern Chiapas, then they have to be treated as two species

by anyone’s definition, and there is no need for further discussion. As for English names, retention of

Rufous-capped for rufifrons can be justified under our guidelines,

because that was the same name used for it when treated previously as a

separate species. Chestnut-capped is also well-justified as the name for that

species through historical usage and appropriateness. I like the “-capped”

common theme, also.”

Comments from David Donsker (voting

for Bonaccorso): “B. YES. My votes are to use the well-established

names Rufous-capped Warbler for Basileuterus rufifrons and Chestnut-capped

Warbler for Basileuterus delattrii as discussed by Terry and Dan in

their proposal.”

Comments from Areta:

“A. YES. The sympatry of rufifrons

and delattrii in Chiapas without morphological intermediacy and

without breakdown of their distinctive songs is very strong evidence supporting

their separate species status. Demko et al (2019b*) found that sympatric delattrii

responded more to own vocalizations than to rufifrons, while

allopatric delattrii and rufifrons, as well as sympatric rufifrons

responded equally to homo and hetero playbacks. This adds some evidence on a,

perhaps, asymmetric discrimination, as well as possibly character displacement

in sympatry.

“B. YES to Rufous-capped Warbler

for Basileuterus rufifrons and Chestnut-capped Warbler for Basileuterus

delattrii. I don´t see any need to quit using the Rufous-capped for the

nominotypic rufifrons.

“*Demko, A. D., J. R. Sosa-López, and D. J. Mennill (2019b).

Subspecies discrimination on the basis of acoustic signals: A playback

experiment in a Neotropical songbird. Animal Behaviour 157:77–85.”

Comments from Rasmussen (voting for

Robbins): “YES for Rufous-capped and Chestnut-capped warblers, as for NACC.”

Comments from Bonaccorso: “A. NO,

for two reasons. First, we have no genetic data to back up this decision. What

will happen if there is no substantial genetic differentiation between these

two “species”? Will we lump them back again and be puzzled by the

differentiation in song and morphology? Second, this decision will affect

SACC´s nomenclature but is not based on any South American data (vocal,

morphological or otherwise). What if B. r. mesochrysus (or at least the

Colombian part of it) is another species? We will have to change the names

again to reflect the reality of this taxon. For the sake of stability, why not

wait until the whole complex is well sampled in terms of both distribution and

diversity of characters to make a change?

Comments from Robbins: “A. Based

on the vocal data, I vote YES for recognizing delattrii as a

species.”

Comments from Zimmer: “YES, to

both A and B. As Van noted, the sympatry

of rufifrons and delattrii in southern Chiapas alone dictates

that they be treated as distinct species.

However, I am particularly impressed by the results of the vocal

analysis by Demko et al. (2020). Their

spectrograms and PCA figure make clear that the songs of the rufifrons-group

and the songs of the delattrii-group, both from areas of allopatry and

sympatry, are distinct, and confirm that salvini belongs with rufifrons

and not with delattrii, as supported by morphometrics, but potentially

confused by intermediacy of some plumage characters. My personal initial field experience with

these taxa was with members of the rufifrons-group in Mexico, and when I

subsequently encountered delattrii in Costa Rica and Panama, I was

struck by how different the songs were.

It’s nice to see the visual representation of these differences! I appreciate Elisa’s concerns regarding the

lack of genetic data in Demko et al. (2020), as well as the lack of data points

from the isolated Colombian range of mesochrysus, but to me, genetic

distance is just one more character when considering species-limits – it

doesn’t carry more weight than any other character set. If we can demonstrate diagnostic

morphometric, plumage and vocal characters, and show that the two forms exist

in sympatry, with assortative mating and lack of obvious hybrids or

intergrades, then it shouldn’t really matter if they haven’t diverged

genetically that much. As for what

happens if and when Colombian mesochrysus proves to be worthy of

elevation to species rank, that’s a simple fix too. I think it is extremely unlikely that

Colombian mesochrysus would cluster with rufifrons, either

vocally or genetically, given that more proximate populations of delattrii

(including sympatric ones) are so clearly different from rufifrons. So, when Colombian mesochrysus is

sampled, the results will either confirm that it belongs with delattrii,

or, that it should be split from delattrii, which would retain its

English name, and the isolated Colombian mesochrysus would require a new

name. Waiting to correct obvious

taxonomic problems due to potential complications that could arise from

currently unsampled populations is a sure-fire recipe for stagnation in my

opinion. If the unsampled populations

are geographically intermediate with respect to the range of the group as a

whole (making it impossible to discount clinal variation), or, if the unsampled

population(s) are from actual or potential contact zones, then, I would agree

that discretion and waiting for additional sampling is warranted. But, in this case, we’re talking about a

peripheral, isolated population at the southern extreme of the overall group

range, and I don’t think the lack of clarification regarding its status should

keep us from advancing the ball downfield.

As for the question of English names, I think the proposed one of

retaining “Rufous-capped” for rufifrons, and resurrecting the previously

established name of “Chestnut-capped” for delattrii is, by far, the most

sensible and least disruptive option.”

Comments from Stiles. “A. YES. B. YES for Rufous-capped and Chestnut-capped,

as recommended by NACC.”

Comments

from Kimball Garrett (voting for Del Rio):

“A.

YES -- Concern about the absence of

genetic data is understandable, but given the fuzzy relationship between

genetic distance and species-level status it seems unlikely that any such

analysis would yield a strong argument either way regarding these taxa. To the

many arguments for recognizing two species put forth by NACC members and within

the SACC I would add (or underscore) the significance of the difference in call

notes (especially the simple ‘chip’ call) between rufifrons and delattrii.

Recordings available in the Macaulay archive not only provide evidence for

clear differences in songs, but also in the chip calls. This difference was

commented upon by Howell and Webb (1995); Howell described the call of delattrii

as “…suggesting a Hooded Warbler (quite distinct from Rufous-capped Warbler).”

Call note differences in oscine passerines may be as informative taxonomically

as songs, if not more so.

“B.

YES -- It is completely reasonable to use the long-established names

“Rufous-capped” and ”Chestnut-capped” for the two species involved, thus aligning with NACC and many other

publications. [Though admittedly the names could be reversed and be equally

descriptive.]”

Comments from Claramunt: “YES. The

congruence of plumage and vocal variation indicates the presence of two

separate lineages with no sign of intergradation despite sympatry.”