Proposal (1044) to South American Classification Committee

Treat Formicarius destructus as a separate

species from F. nigricapillus

Effect on SACC list

If

this proposal passes, it will result in the elevation of the taxon destructus to full species, resulting in

a monotypic F. nigricapillus and a

monotypic F. destructus.

Background information

The

current SACC note reads”

"1c.

Areta & Benítez Saldívar (2025) provided vocal evidence for treating South

American destructus as separate species.

SACC proposal needed."

Areta & Benítez Saldívar (2025) summarized the

situation as follows:

The

Black-headed Antthrush (Formicarius

nigricapillus) includes two allopatric subspecies: nominotypic nigricapillus in Costa Rica and Panama,

and destructus in Colombia and

Ecuador (Ridgway 1893; Hartert

1898; Wetmore 1972; Krabbe and Schulenberg 2003, 2020). Although the taxon nigricapillus

was originally described as a full species by Ridgway (1893) and treated as

such by some authors (Chapman 1917, Cory & Hellmayr 1924), it was often

considered as a subspecies of the Black-faced Antthrush (F. analis) (Hartert 1902, Ridgway 1911). Conversely, the taxon destructus was originally described as a

subspecies of F. analis by Hartert

(1898) and was subsequently either considered as such (Hartert 1902), rarely

afforded species-level status (Salvadori and Festa 1899; Howell and Dyer 2022),

or most often considered as a subspecies of F.

nigricapillus (Chapman 1917, Cory & Hellmayr 1924, Wetmore 1972, Krabbe

& Schulenberg 2003).

New information

In

Areta & Benítez Saldívar (2025), we assessed species limits in F. nigricapillus using vocal, plumage,

and morphometric data, concluding that nigricapillus

and destructus are better treated as

two separate biological and recognition species. For more detailed explanations

and discussions stemming from historical taxonomic references, please refer to

the publication. What follows is a blend of selected copied and reorganized

text and images from Areta & Benítez Saldívar (2025) with some minor

adjustments to facilitate reading.

Songs: After discarding

duplicates, Areta & Benítez Saldívar (2025) compiled a total of 57 songs of

nigricapillus and 129 songs of destructus that were assessed aurally

and through examination of spectrograms. The song of nigricapillus is a

rapid series of around 25 clear, pulsated whistled notes that begins with a few

more spaced notes that become mostly evenly paced with a slight rise in pitch

halfway through the song and a relatively monotonous ending (sigmoid-like

spectrographic contour; Fig. 1). The song of destructus is a very rapid eerie series of around 40 ventriloquial

notes that fall and rise in pitch and decrease markedly in pace in the second

half (smile-like spectrographic contour; Fig. 1). The vocalizations of nigricapillus

and destructus have been described

accurately in field guides, but the importance of their differences has not

been fully realized. The song of nigricapillus

was described as "a rapid, pulsating series of ca. 20 deep, resonant,

whistled notes, the first 2-3 slower, more staccato, the next 6-8 rising in

pitch, the last 10-12 on the same pitch, with the final 2 notes slower, the

entire series lasting 4-5 sec" (Stiles and Skutch

1989, p. 287), while that of destructus "resembles that of

Rufous-capped Antthrush, but shorter, an eerie, quavering glissando of about 30

notes in 3 sec, sliding upscale and slowing noticeably at the end;

ventriloquial" (Hilty and Brown 1986,

p. 417). The song of nigricapillus has been aptly likened to

the shorter song of Thicket Antpitta Myrmothera

dives ( Garrigues and Dean

2007; Vallely and Dyer 2018), a comparison that does not apply to the song of destructus.

The

quantitative acoustic characterization evidenced that songs

of both taxa are 100% diagnosable (n=21 nigricapillus,

n=38 destructus). Acoustic data showed that 13 out of 15 variables differed significantly

between nigricapillus and destructus, the differences in 10 of

these 13 variables were very marked with non-overlapping mean ± SD,

automatically indicating that they belong to statistically different

populations. Taxon nigricapillus

showed lower song peak frequency, longer mean note duration and mean interval

between notes, fewer notes per song, slower pace, relatively even pace in the

first and second halves of the song, lower peak frequencies of first, median,

and final note, and longer duration of first, median, and final note. In

contrast, destructus had higher song

peak frequency, shorter mean note

duration and mean interval between notes, more notes per song, faster pace, a

marked deceleration in the second half of the song, higher peak frequencies of

first, median, and final note, and shorter duration of first, median, and final

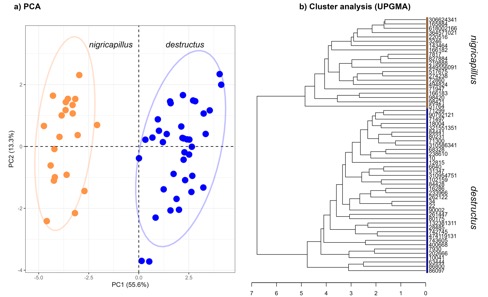

note (Table 1). The songs of both taxa were clearly separated in

multivariate space (Fig. 2A) and a cluster analysis also revealed two

distinctive groups, unambiguously including all destructus samples

clustered separately from all nigricapillus recordings (Fig. 2B).

The

song of nigricapillus remains

essentially identical through ca. 490 km across Costa Rica and into C Panama in

our sample. t]The song of destructus also

remains basically the same through its distribution, ca. 1130 km extending from

NC Colombia to SW Ecuador. The diagnostic song types are separated by a gap of

ca. 190 km between NW Colombia (Jardín Botánico del Pacífico, Chocó) and

E Panamá (Nusagandi, Guna Yala), and exhibit no sign

of intermediacy closer to their respective limits (Fig. 1). Further documented

records are needed to properly understand the actual distributional gap between

nigricapillus and destructus. The width of the gap is at

least 190 km as shown by our song-recordings dataset, but possibly much

smaller: birds seen, heard, and tape-recorded at Cuchilla del Lago on the

Colombian side of the Serranía de Darién in the Cerro Tacarcuna (Renjifo et al.

2017) most likely represent the taxon nigricapillus. This would reduce the gap

between nigricapillus (Cuchilla del

Lago; see question mark in Figure 1) and destructus

(Reserva La Bonga) to 100 km within Colombia. Unfortunately, the sound

recordings were not available at the time of our writing and could not be

assessed (J. Avendaño in litt.). Further fieldwork should clarify the extent of

their allopatry and assess whether the Río Atrato and its formidable swamps act

as a biogeographic barrier for these taxa (Haffer 1970, 1975, Renjifo et al.

2017). The Cerro Tacarcuna records, if confirmed to be nigricapillus (which seems very likely), would indicate that both

taxa (nigricapillus and destructus) occur in South America.

Fig. 1. Plumage

aspect, songs, and geographic distribution of

songs of Black-capped Antthrush (Formicarius

nigricapillus), and Black-hooded Antthrush (F. destructus) analysed in this study. Orange circles: F. nigricapillus (photo: ML-452131711, San

Gerardo Biological Station, Costa Rica, by

Mark Hebblewhite; song: ML-220516, Reserva Biológica Bosque Nuboso

Monteverde, Costa Rica by D. L. Ross).

Blue circles: F. destructus (photo: ML-121617911, Rio Silanche Bird

Sanctuary, Ecuador by Nick Athanas; song: JIA-10, Reserva de Bosque Seco Lalo Loor, Ecuador by J. I. Areta). Circles

with a central dot denote songs measured quantitatively; plain circles denote

songs studied aurally (see Appendices 1 and S1); question mark (?) indicates

unconfirmed sound recording of nigricapillus

from Cerro Tacarcuna in Colombia. The differences in plumage (chestnut nape in nigricapillus, black nape in destructus), song, and morphometrics

collectively support the recognition of nigricapillus

and destructus as separate species.

Table 1. Acoustic parameters

of songs of Black-capped Antthrush (Formicarius

nigricapillus), and Black-hooded Antthrush (F. destructus). Values shown are mean ± SD [range], n= sample size.

Asterisk denotes significant statistical differences in the Mann-Whitney

non-parametric test (α<0.05), and plus symbol denotes non overlapping mean ±

SD. See Appendix 1 for measured sound recordings.

|

Variable |

F. nigricapillus (n=21) |

F. destructus

(n=38) |

|

Bandwidth 90% (Hz) |

205.35±56.37 [93.8-281.2] |

207.93±38.45 [140.6-281.2] |

|

Duration 90% (s)* |

2.38±0.33 [1.74-3.00] |

2.64±0.44 [1.92-3.88] |

|

Peak frequency (Hz)* + |

1484.37±61.75 [1406.2-1593.8] |

1689.91±61.7 [1546.9-1781.2] |

|

Mean note duration (s)* + |

0.06±0.01 [0.05-0.09] |

0.04±0.01 [0.02-0.07] |

|

Mean interval between notes (s)* + |

0.08±0.01 [0.05-0.10] |

0.04±0.01 [0.03-0.06] |

|

Number of notes*+ |

24.95±1.69 [22-29] |

37.62±5.57 [28-52] |

|

Sound density |

0.56±0.06 [0.46-0.67] |

0.6±0.08 [0.47 - 0.79] |

|

Pace*+ |

5.98±0.42 [5.44-6.96] |

9.61±1.09 [7.76-11.81] |

|

Pace change (second/first half)* + |

1.04±0.09 [0.88-1.19] |

0.76±0.07 [0.63-0.93] |

|

(8.63±1.2/11.37± 1.08) [5.61-6.67/5.25-7.58] |

(6.18±0.32/5.99±0.66) [6.82-11.46/9.02-12.82] |

|

|

Peak frequency first note (Hz)* + |

1345.97±68.13 [1218.8-1500] |

1650.24±93.23 [1406.2-1781.2] |

|

Peak frequency median note (Hz)* + |

1412.91±47.54 [1312.5-1500] |

1617.82±58.76 [1453.1-1781.2] |

|

Peak frequency final note (Hz)* + |

1477.67±60.46 [1406.2-1593.8] |

1703.12±69.11 [1546.9-1875] |

|

Duration first note (s)* |

0.04±0.02 [0.01-0.06] |

0.02±0.01 [0.01-0.03] |

|

Duration median note (s)* + |

0.09±0.02 [0.04-0.14] |

0.12±0.03 [0.04-0.10] |

|

Duration final note (s)* |

0.14±0.04 [0.10-0.26] |

0.11±0.03 [0.06-0.21] |

*=non-parametric Mann-Whitney test P-value <.05

+=non-overlapping mean ± SD

Plumage: To characterize the

external appearance of nigricapillus

and destructus, Areta & Benítez

Saldívar (2025) examined photographs of 37 museum

specimens, including the holotypes of both taxa, and vetted 40 good-quality

photographs on the citizen science platforms eBird (ebird.org) and iNaturalist

(inaturalist.org). They found that nigricapillus exhibits chestnut-brown

hindneck (sometimes extending to neck sides in a handkerchief or semicollar; Figure 1), and typically more chestnut-brown

back (Fig. 1), whereas destructus exhibits all-black hindneck and neck

sides (Fig. 1), and typically browner back. There is some variation in back

colour of specimens (but not in the back-neck contrast that distinguishes

taxa), with some nigricapillus being

seemingly identical in colour to typical destructus

(Chapman 1917,

USNM specimens). In some nigricapillus

individuals, the chestnut-brown hindneck is extensive and expands onto the

sides of the neck creating a semicollar, which gives

these individuals a capped aspect, that is less prominent in birds with less

extensive chestnut-brown hindneck. On the other hand, all individuals of destructus show a hooded aspect, caused

by its wholly black head, hind neck and neck sides (Fig. 1).

Fig. 2.

Quantitative analyses of songs of Black-capped

Antthrush (Formicarius nigricapillus),

and Black-hooded Antthrush (F. destructus). (A) Plot of the first two principal components (PC1 vs.

PC2) of the Principal Component Analysis. Ellipses depict 95% confidence

intervals. (B) Dendrogram from the agglomerative hierarchical

cluster analysis (UPGMA). Both methods consistently

show that nigricapillus and destructus differ markedly in songs

supporting their treatment as separate species. See Appendix 1 and S1 for songs

measured.

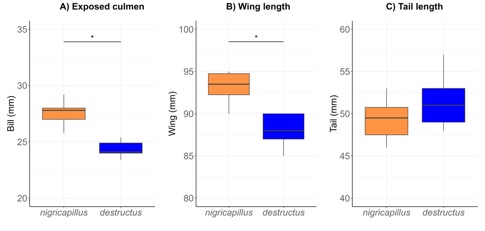

Morphometry: based on a limited

dataset (n=6 nigricapillus, n=9 destructus), Areta & Benítez

Saldívar (2025) concluded that 1) bill length (exposed culmen) showed no

overlap between taxa, with all individuals of nigricapillus having a longer bill than destructus, and therefore no overlap in mean ± SD values (Fig. 3a),

2) nigricapillus was longer winged

than destructus, with exact overlap

only in their extreme values, and no overlap in mean ± SD values (Fig. 3b), and

3) tail length was longer in nigricapillus

than in destructus, but the

difference was not statistically significant (two tailed t-test p=0.17) (Fig.

3c).

Fig. 3. Morphological measurements of Black-capped Antthrush (Formicarius nigricapillus), and

Black-hooded Antthrush (F. destructus).

Figure depicts median and quartiles on box plots. Asterisk denotes significant

statistical differences in one-way ANOVA (α<0.05). The

morphological differences in bill and wing length coupled to plumage

differences give support to the treatment of nigricapillus and destructus

as separate species. See Table 2 for sample sizes and data, and

Appendix 2 and S2 for specimens measured and studied.

The differences in songs and plumage herein

described can be readily appreciated in videos of free-ranging singing birds:

nigricapillus: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/608419951

destructus:

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/316228641

Taxonomic assessment

The

marked differences in vocalizations and morphology, and moderate but consistent

plumage differences strongly supports the elevation of the taxon destructus to species-level, leading to

the recognition of two allopatric and monotypic species, F. nigricapillus and F.

destructus. Areta & Benítez Saldivar (2025)

based their taxonomic conclusions on the recognition concept of species (Paterson 1985), whereas the same species would be recognized by applying

the biological species concept (Mayr 1963; “isolation

concept” fide Paterson 1985). The inferred level of discontinuity between nigricapillus and destructus is of such a magnitude that presumably any other modern

species concept would recognise them as separate

species, whether based on mating or other important attributes, phenotypic

distinctiveness, presence of autapomorphies, or phylogenetic independence

(Cracraft 1983, Mishler & Brandon 1987, Gill 2014, Areta et al. 2019,

Winker 2021). Howell & Dyer (2022:27) wrote that "Differences in plumage and song indicate that Central

American nigricapillus and South American destructus (Choco

Antthrush) are best treated as separate species." A view that is amply

supported by Areta & Benítez Saldivar (2025).

In

terms of plumage, the differences between nigricapillus

and destructus (Fig. 1) would be

among the least conspicuous for two Formicarius

species-level taxa, and comparable to (although less obvious than) those

between F. moniliger and F. analis. They differ most notably by

the presence of a rufous-chestnut fore-collar below the black throat in moniliger, whereas the black throat

contacts the grey chest directly in the two subspecies groups of F. analis

(Howell 1994, Vallely and Dyer 2018). However, less obvious plumage differences

exist between the analis and hoffmanni subspecies groups within F. analis despite their noticeable vocal

differences (Howell 1994) which are compatible with species-level differences

in the genus (Krabbe and Schulenberg 2003, van Dort et al. 2023, Benítez

Saldívar & Areta in prep.).

Common names

Most

species in the genus Formicarius

carry common English names that refer to plumage features. We propose to adopt

the name Black-capped Antthrush for F.

nigricapillus and Black-hooded Antthrush for F. destructus, which focus on one of the main plumage differences

between them and retain a connection to the former Black-headed Antthrush used

for the composite species. We find the proposed use of Black-hooded Antthrush

for F. nigricapillus by Howell and Dyer (2022) to be misleading, as this taxon is capped rather than

hooded. The smaller bill of destructus

is difficult to appreciate in field conditions, and bill features do not seem

useful to coin common names here. Finally, Choco Antthrush has been proposed

for destructus (Howell and Dyer 2022); although a good name, there are other antthrushes in the

Choco, and it loses the connection to the former Black-headed Antthrush name.

Voting and

recommendations

Perhaps

the best thing to do is to vote on three different aspects of the proposal:

A) Species limits: We

recommend a YES vote to split F.

destructus from F. nigricapillus.

B) English names: We

recommend a YES vote to adopt the name Black-capped Antthrush for F. nigricapillus and Black-hooded

Antthrush for F. destructus

C) Presence of nigricapillus in Colombia. A lingering

question is whether the Cerro Tacarcuna records in Colombia should be

provisionally considered to be nigricapillus

until shown otherwise. For biogeographic reasons, we lean towards the

maintenance of nigricapillus in the

SACC list based on these records, as it seems unlikely for destructus to reach the Cerro Tacarcuna crossing the Atrato swamps.

We recommend a YES vote to keep F.

nigricapillus in the SACC list.

References

Areta JI, Depino EA, Salvador SA, Cardiff SW,

Epperly K, Holzmann I (2019) Species limits and biogeography of Rhynchospiza

sparrows. Journal of Ornithology 160:973-991

Areta,

J.I., Benítez Saldívar, M.J. (2025). Species limits in the Black-headed Antthrush (Formicarius

nigricapillus). J Ornithol

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-025-02265-5

Chapman

FM (1917) The

Distribution of Bird-Life in

Colombia. A Contribution to a Biological Survey of. South America.

Bull. Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist., 36.

Cory CB, Hellmayr CE (1924) Catalogue of

Birds of the Americas. Publications of the Field Museum of Natural History

(Zoological Series). Volume 13, Part 3. Chicago.

Cracraft J (1983) Species concepts and

speciation analysis. Curr Ornithol 1:159–187

Garrigues R, Dean R

(2007) The Birds of Costa Rica. Zona Tropical, Comstock Publishing

Associates, Cornell University Press.

Gill F (2014) Species taxonomy of birds:

which null hypothesis? Ornithological Advances 131: 150–161

Haffer J (1970)

Geologic-climatic history and zoogeographic significance of the Urabá region in

northwestern Colombia. Caldasia 10: 603–636.

Haffer J (1975) Avifauna of

northwestern Colombia, South America. Bonner Zoologische Monographien 7: 1–182.

Hartert E (1898) On a

collection of birds from north-western Ecuador, collected by Mr. W. F. H.

Rosenberg. Novitates Zoologicae 5: 477–505.

Hartert E (1902) Some

further notes on the birds of north-west Ecuador. Novitates Zoologicae 9: 599–617.

Hilty SL, Brown WL (1986) A

Guide to the Birds of Colombia. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Howell SNG (1994) The

specific status of black-faced antthrushes in Middle America. Cotinga 1: 20–25.

Howell SNG, Dyer D (2022). Costa Rica

even richer than we thought? North American Birds 73:

22–33.

Krabbe NK, Schulenberg TS (2003).

Black-headed Antthrush (Formicarius nigricapillus). In Handbook of the

Birds of the World Alive (del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Sargatal J, Christie DA, de

Juana E, eds). Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Krabbe NK, Schulenberg TS (2020). Black-headed Antthrush (Formicarius nigricapillus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (del

Hoyo J, Elliott A, Sargatal J, Christie DA, de Juana E, eds). Lynx Edicions,

Barcelona.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.blhant1.01

Mayr E (1963) Animal species

and evolution. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Paterson HEH (1985) The

recognition concept of species. In: Vrba ES (ed) Species and speciation.

Transvaal Museum Monograph, Pretoria.

Mishler BD, Brandon RN

(1987) Individuality, pluralism, and the Phylogenetic Species Concept. Biology

and Philosophy 2: 397–414

Renjifo LM, Repizo A, Ruiz-Ovalle JM, Ocampo S, Avendaño JE (2017) New

bird distributional data from Cerro Tacarcuna, with implications of

conservation in the Darién highlands of Colombia. Bulletin of the British

Ornithologists´ Club 137: 46–66.

Ridgway R (1893) A revision

of the genus Formicarius Boddaert.

Proceedings of the United States National Museum 16: 667–686.

Ridgway R (1911) The Birds

of North and Middle America: A Descriptive Catalogue. Part V. Bulletin of the

United States National Museum 50.

Salvadori

T, Festa E. 1899. Viaggio del Dr. Enrico

Festa nell’Ecuador. XXI. Uccelli. Parte seconda - Passeres clamatores.

Bollettino dei Musei di Zoologia ed Anatomia Comparata della R. Università di

Torino 15 (362): 1–34.

Stiles FG, Skutch AF (1989) A

Guide to the Birds of Costa Rica. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Vallely AC, Dyer D

(2018) Birds of Central America. Princeton University Press, Princeton

and Oxford.

van Dort J, Patten MA,

Boesman PFD (2023). Black-faced Antthrush (Formicarius analis), version

2.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of

Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.blfant1.02

Wetmore A (1972). The

Birds of the Republic of Panamá. Volume 3. Passeriformes: Dendrocolaptidae

(Woodcreepers) to Oxyruncidae (Sharpbills). Smithsonian Miscellaneous

Collections 150(3). Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., USA.

Winker K (2021) An overview of speciation and species limits

in birds. Ornithology 138: 1–27

10.1093/ornithology/ukab006

Links to supplementary

information:

Addendum:

Genetics: The coincidental

break in plumage and vocalizations between F.

moniliger and F. analis umbrosus

(a representative of the hoffmanni

group) were used as arguments to support the elevation of moniliger to species status (Howell 1994). More recently, phylogenetic data have shown that F. moniliger is sister to a clade

including F. destructus as more

closely related to F. analis

(including representatives of the hoffmanni

and analis subspecies groups) (Harvey et al. 2020). This distant relationship between moniliger and analis

further reinforces the species-level split of F. moniliger and lends support to vocal differences as a useful

tool to establish species limits in Formicarius.

Although there are no available genetic data for nominotypic nigricapillus, the vocal distinctions

between nigricapillus and destructus seem as or more marked than

those between F. moniliger and F. analis of the analis and hoffmanni

subspecies groups. In our paper we predicted that nigricapillus and destructus

will exhibit levels of genetic differentiation tantamount to their vocal and

morphological distinctions.

The

Formicarius phylogenetic tree from

Harvey et al. 2020:

Harvey

MG, Bravo GA, Claramunt S, et al. (2020) The evolution of a tropical

biodiversity hotspot. Science 370: 1343–1348.

Juan

I. Areta and M. Juliana Benítez Saldívar, April 2025

Voting chart: https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart1044+.htm

Comments

from Remsen:

“A. YES. Although

playback trials would be nice, the degree of difference in the songs is

consistent with species rank, and burden-of-proof falls on those who would

treat them as subspecies.

“B. MAYBE, for all the

good reasons outlined in the proposal, especially maintaining the connection

between old and new names. Also, follows

SACC guidelines (https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCEnglishNameGuidelines.pdf)

for providing new names for both daughters in a parental split. After having looked through Macaulay photos

of dozens of destructus, “hooded” seems especially appropriate for the

extent of the black. The match between

the scientific and English names for nigricapillus is helpful in

remembering both. However, as for nigricapillus,

a problem is that “capped” is typically used for cases in which the bird has a

much more distinctive color patch on the top of the head, which is not really

the case for nominate ruficapillus, despite the scientific name. Obviously, the scientific name reflects a

pattern seen on specimens, but I think we need side-by-side photos of the

specimens, if only as confirmation that the name is OK.

“C. YES, but somewhat

reluctantly because the recordings are unavailable and because perhaps the

Colombian national committee should have the say on this one. On the other hand, to propose that the

records are not nigricapillus makes no biogeographic sense, and I agree

with this statement in the proposal “Cerro Tacarcuna records in Colombia should

be provisionally considered to be nigricapillus

until shown otherwise.”

“Anecdote: puzzled by

the name destructus, I looked at Jobling (online), and here is the

derivation from Hartert’s 1898 description: ‘very much destroyed by the shot, but still quite recognizable, is so

considerably smaller and darker brown above than typical analis that I

do not hesitate to distinguish it subspecifically’.”

Comments

from Lane:

“I must admit this one was not on my radar (although I have seen, and heard,

both taxa). The voices are much more distinct that I was expecting, and I think

the results of the study presented are good.

“A) YES to splitting

the two members of the complex as biological species.

“B) The two daughter

species are not all that strongly differentiated by plumage, and really can't

see F. nigricapillus having a distinctive black crown set off against

the rest of the head (I suspect the name was coined because it was

blacker-crowned than F. analis... and granted, I am looking at the

poorly-lit Macaulay photos rather than specimens to make this statement), but

unless we want to get derailed by another English name situation, I will go

with the names suggested: Black-crowned and Black-hooded.

”C) YES to retaining

both species in the SACC area due to the records from the border near Panama.”

Comments from Rasmussen

(who has Robbins’ vote): “B. Re the suggestion that the presence of other

antthrushes in the Choco makes Choco Antthrush for destructus less than

a great name, I don't see the issue there. As far as I can see, destructus is

the only antthrush in the majority of lowland Choco,

and certainly it is the only one recognized as a species that is largely

confined to the Choco (unless I'm missing something---please correct if so).

Here are maps of the three other species in the region:

“There are a smattering

of Black-faced eBird reports for the Choco but no photos.

“Rufous-breasted is in

the western Andes but not lowland Choco:

“Schwartz's Antthrush

is also in the Andes, not the lowlands.

“All the others

currently called antthrushes are either eastern slope or nowhere near the

Choco.

“Thus, I'm voting for

Choco Antthrush for destructus. I think Black-hooded is OK too.

“In the absence of

something better, I'm still OK with Black-capped for nigricapillus,

especially given the sci name.”

Additional comments

from Remsen:

“Terry Chesser graciously sent me photos of the USNM specimens of nigricapillus

(1) and destructus (4). I have

lightened up the originals, and done some cropping and rearranging so that the

specimen of nigricapillus is always at the top, above the yellow line:

“Dorsal:

“Lateral:

Ventral:

“As

noted by Terry, there does not seem to be much in the way of difference between

the two in plumage, especially in how “capped” the two are. Of course, with only 1 nigricapillus, it’s

tough to assess this, but I am backing off of the proposed English names and

going with the names used by Howell and Dyer (2022), which have the additional

advantage of already having been in print for 3 years. Also, as shown by Pam, destructus is “the”

Antthrush of the Chocó. As much as I

appreciate the logic of the proposed names, I am switching my vote on B to NO

unless additional information indicates that nigricapillus has a ‘capped’

appearance.”

Comments

from Terry Chesser: “If destructus

is more closely tied to the Choco than any other antthrush,

then I agree with Pam that Choco Antthrush is a perfectly good name. The name Black-hooded Antthrush, although

suggested in the proposal for destructus, is also applicable to nigricapillus,

and in my view is more appropriate for nigricapillus than Black-capped,

which despite matching the scientific name doesn't seem to be particularly

suitable (as others have noted). Black-headed or Black-hooded, yes, but not

Black-capped, at least in the way that "capped" is typically used. A bonus is that Black-hooded for nigricapillus and

Choco for destructus were used in 2022 by Howell and Dyer, so

there's a bit of precedence there.”

Additional

comments from Areta:

“I find hooded for nigricapillus a terrible name. Look at photos of live

birds in their habitat, and you´ll see how strikingly different is the hood of destructus

(which gives it a bold hooded appearance) from the brown nape (and sometimes

neck sides) of nigricapillus, which very often gives it a capped appearance

(and if one would like to call this hooded, then it is obviously much, much,

much less hooded than destructus, to the point that the name results in

confusion, because one would be calling hooded the presumed sister species that

is less hooded). Choosing a species name based on a feature that is more

prominent in its sister species seems to be a bad choice to me.

“Note

also that ALL the field guides (including the latest from Costa Rica by Howell

and Dyer) have erred, and they have illustrated destructus instead of nigricapillus.

“Here

some random nigricapillus photos:

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/622843058

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/622070151

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/613829664

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/601316591

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/452110921

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/153191961

“And

some destructus:

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/205559781

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/184627131

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/121617911

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/76928221

“Anyway,

I stand by the names we proposed in the paper.”

Comments

from Gary Rosenberg (voting for Claramunt): “I vote YES with regard to

Black-capped for nigricapillus and Black-hooded for destructus

- as it has been demonstrated on looking at the photos that Nacho provided that

nigricapillus is really visually more “black-capped” in comparison to destructus

– with destructus having a more extensive black hood. Although seeing

those differences in the field may be difficult. I personally would retain

“Black-headed” for nigricapillus, but I guess that isn’t an option - we could

use Black-headed and Choco Black-headed - or if retaining Black-headed is

really against the rules, then using Black-capped for nigricapillus would be

acceptable - it therefore would align with the scientific name. I am not

against the idea of using “Choco” for destructus, but I don’t believe it

is the only antthrush there - or at least it is a

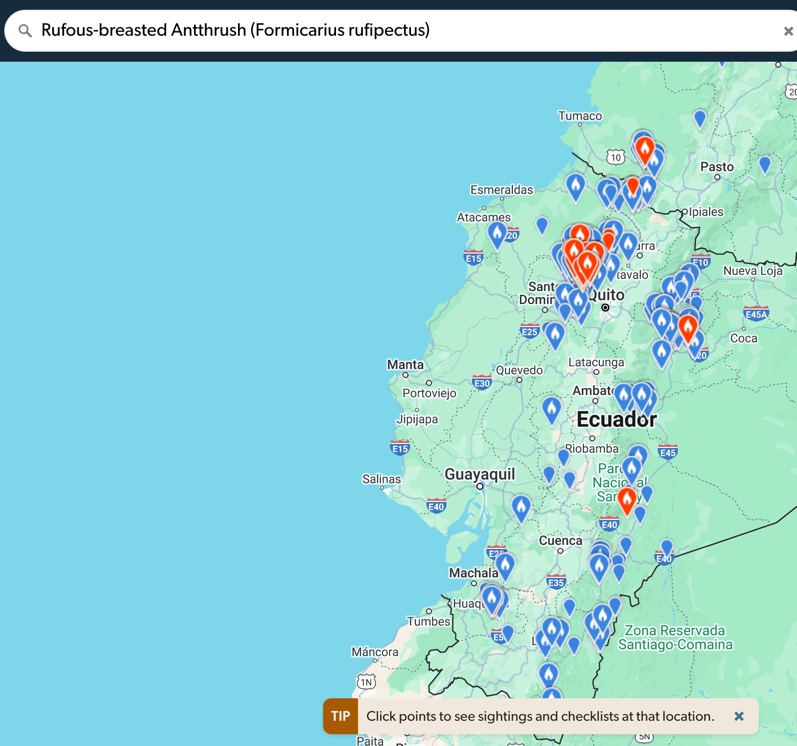

matter of semantics. In western Ecuador,

“destructus” ALMOST overlaps with Rufous-breasted - the two are

separated by elevation, but I would NOT be surprised if the two overlap (and I

suspect they do overlap around Mindo) – nigricapillus and

Rufous-breasted overlap in elevation in Costa Rica (I have seen the two on the

same trail in Braulio Carrillo NP). Here is a more specific map of where

Rufous-breasted occurs in Ecuador - therefore the idea that destructus is

the only antthrush in the “Choco” is a bit misleading

- in my opinion. One can make the argument that the “Choco” is not limited

specifically to the lowlands but also includes the foothills. Furthermore, destructus

does occur south along the slopes of the Andes in Ecuador south to about

Guayaquil - south of the area generally described as the Choco - although the

majority of the distribution is within the Choco for sure.

“I

guess I prefer using Black-hooded for destructus, it is at least similar

to “Black-headed” and as the authors say, retains that connection, but I would

not have an issue with using Choco for destructus, as the majority of

the bird’s range is in the Choco.”

Additional

comments from Remsen:

“I am flip-flopping back to YES on this one after seeing the photos for which

Nacho provided the links. I am also

strongly persuaded by his excellent point that using “hooded” for nigricapillus

would be a bad idea given that “black-hooded” is more appropriate for its

sister taxon.”

Comments

from Josh Beck (guest vote):

“Essentially

there are two good and suitable and relatively unproblematic names for destructus

suggested/available (Black-hooded and Choco) and two slightly more problematic

and less well received names suggested/available for nigricapillus (Black-capped

and Black-hooded).

“Viewing

this pragmatically, I don't think any of the proposed names are really going to

cause any issues. This is not a group of birds where confusion reigns supreme

or where there is such a diversity of species that we're entering into name

soup. Formicarius are almost universally first detected and ID'd by voice and overlapping species are different enough

from each other that subtle details of names aren't going to impact visual

field ID either. Nor do I think someone working in a museum is likely to get

thrown off the track by the common name Black-capped.

“I

agree that Black-hooded for nigricapillus is suboptimal given that it is

less hooded than destructus. I don't personally see nigricapillus as

particularly capped (the contrast vs the cheek argument put forward earlier)

but being pragmatic, this name is not going to cause a slew of mis-ID's in the

field or mayhem in collections. Whatever

your views of the cheek needing to contrast or not, nigricapillus does

have black on the cap/crown and it aligns with the scientific name, so I am

fine with Black-capped for nigricapillus. Further, I also think

NACC should have priority on the naming of this one, so I'm not sure that this

vote really matters but Black-capped is my vote for nigricapillus.

“For

destructus I really think either Black-hooded or Choco serves just

fine. I favor and vote for Black-hooded for two reasons:

1) Alignment with Black-capped and with the

original name, Black-headed.

2) Given that at some

point Black-faced Anthrush, F analis is likely going to be split, I think it's

quite likely we'll end up with Amazonian and Central American Antthrush as

common names and those will pair well with Mayan, so perhaps avoiding a

geographic descriptor for destructus helps to keep a bit of name

alignment not just now but also in a future split of Black-faced.”

Additional

comments from Josh Beck (guest vote): “I had assumed that Black-headed would be too

disagreeable.

“Without

having requested a data dump from eBird to get precise numbers, a quick look at

eBird and Macauley and XC shows that, as expected, both daughters are commonly

observed. I would estimate destructus is a bit more commonly observed,

perhaps a 60/40 split in data, give or take. For me this doesn't particularly

impact a vote in this case but wanted to put the info out there in case it

sways others.

“I

personally have no problem with Black-hooded and Black-capped but would prefer

Black-headed and Black-hooded and am not worried about confusion here, so would

vote for Black-hooded and Black-headed. I am actually quite catholic as well

about which of the two carries which name. Black-headed for nigricapillus

if it is viewed as more appropriate, or Black-hooded for nigricapillus if

there is desire to align with Howell & Dyer's recent precedent.”

Comments

from Andrew Spencer (voting for Naka): “I've also really been enjoying the

discussion around these names! I've given myself a couple of days to think

about these, and my initial gut reaction hasn't changed that much: I'm

relatively ambivalent about the proposed names, but I am very against keeping

the old name around (unless it's as compound names for both split species,

which is probably overkill here). The fact that we have to even think about

which one is better to use the old name for is especially a red flag for

me that we should be retiring it if at all possible. If this was an instance

where there was absolutely no acceptable options for one of the split species I

might be more accepting of retaining the pre-split name, but I don't think that

is the case here.

“On

to the various names that people have proposed. I honestly think that the

"capped" look of nigricapillus is, at best, very

subtle. And for the times that it is most apparent, the "cap"

looks very dark brown contrasting with the black elsewhere on the head, rather

than truly "Black-capped". That being said, it would hardly be the

first time a common name draws attention to a subtle plumage feature, and I

prefer "Black-capped" over retaining the old name by many miles.

“’Black-hooded’

is ok for destructus. I'm also completely fine with ‘Choco’, but the

symmetry of using plumage features for the two split species tilts my vote

towards that for this bird as well.

“So,

my official vote for now is to follow the names Nacho originally proposed. If

that ends up not passing though, and we're spit-balling new names, what about

using "Central American Antthrush" for nigricapillus, and

then "Choco Antthrush" for destructus? At the moment

there are no other antthrushes endemic or almost entirely limited to Central

America (unless you consider the Yucatan part of Central America). When

Black-faced Antthrush ends up getting split, the vocal type in Central America

makes it well into Colombia, so contra what Josh says I think the name

"Central American" works better for nigricapillus than it will

for that eventual species.”

Comments

from Naka:

“A) Species limits:

YES, I think we can safely consider F. nigricapillus and F.

destructus two separate biological species based on the evidence provided

by Areta & Benítez Saldívar (2025).

“B) English names:

After giving a careful read to all the comments, I would recommend Black-capped

Antthrush for F. nigricapillus and Choco Antthrush for F.

destructus.

“C) As for the presence

of F. nigricapillus in South America (and therefore within our working

area), I agree with Van, in giving a YES vote, but urge the Colombian National

Committee to decide on this one.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“A: YES. C. “YES to maintaining nigricapillus on SA list, given the

number of cases in other groups in which a Central American or Panama species

just makes it into Colombia, suggesting a lack of ecological barriers at this

point.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“A. YES. The data from Areta &

Benítez Salvador (2025), as summarized nicely in the Proposal, are both

clear-cut and convincing, particularly as regards the analysis of differences

in loudsong between the two taxa. In

retrospect, I remember being struck by how different destructus sounded

the only times I encountered it in Ecuador, relative to nigricapillus,

which I knew well from Costa Rica and Panama.

Since my only encounters with destructus were from a single trip

in 1993, one in which every other memory and experience of the trip was

overwhelmed by news of Ted Parker’s death just two days into my trip, I had

frankly forgotten all about looking into the vocal differences any further

until I saw this Proposal. C. YES. Cerro Tacarcuna records in Colombia should

be provisionally considered to be nigricapillus until shown otherwise.”

Comments

from Robbins:

“A. YES. This seems straightforward based on the differences in the primary

vocalizations, so yes for recognizing destructus as a species. C. “YES,

pending decision by Colombian list committee.”

Comments

from Claramunt:

“A. YES. Clearcut differences in song, plumage, and morphology indicate these

are fully separated lineages. C. NO. Correct me if I’m wrong, but the Cerro

Tacarcuna record does not have tangible evidence available for verification.

Therefore, we can’t include F. nigricapillus in our list anymore. The

record doesn’t fulfill our criteria for Inclusion. Votes need to be

reconsidered.”

Additional

comments from Remsen:

“C. I change my vote to NO on this one – I think Santiago’s reasoning is the

way we should go. There is no tangible

evidence that the Colombian report pertains to either species; besides not

having a specimen, photo, or sonogram, the report doesn’t even have a written

description that supports the record as pertaining to either species. I have no doubt that the observers had this

one right, and to think that this could be destructus is

biogeographically implausible. But our

criteria do not allow for “probability” to affect the decision.

“Here

is the account from Renjifo et al.:

‘BLACK-HEADED

ANTTHRUSH Formicarius nigricapillus

Solitary

individuals, or with mixed-species flocks, observed following army-ant swarms

above 1,000 m

at our study site. Previously recorded in the Chocó lowlands at Nuquí north

to Bahía

Solano (D. Calderón-F. pers. comm.), the río Jurubidá

on the Pacific coast (Haffer

1967a, Hilty

& Brown 1986) and Serranía de Abibe (D.

Calderón-F. pers. comm.). The closest

locality in

Panama is Nusagandi, western San Blas (Ridgely &

Gwynne 1989). Black-faced

Antthrush F.

analis inhabits the Urabá region and the Atrato Valley, but the contact zone

between the

two species was not previously known. Haffer (1967a) suggested the Alto del

Buey area (1,810 m), in the Serranía del Baudó, as a

possible contact zone. However, one

record of

Black-faced Antthrush on the Panamanian slope of Cerro Tacarcuna at 1,180 m

(Sullivan et

al. 2009), plus an aural record below 800 m at our study site suggests possible

contact in

the foothills of Cerro Tacarcuna, where the species possibly replace each other

elevationally.

Specimen collection will be necessary to test Haffer’s

hypothesis that the two

species may hybridise in a narrow zone within this region.’

Additional

comments from Stiles:

“C. I´m OK to change my vote to NO in accord with Santiago's comment that there

is no confirmed record of nigricapillus for Colombia.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“A) Yes. The data

(acoustic, genetic, and morphometric) support two good biological species.

“C) NO. Visual reports

should not be enough to include nigricapillus in the SACC list. A

photograph or a good recording could be considered as ‘tangible.’"

Additional

comments from Zimmer:

“C. I’ll switch my vote on this to adhere to our criteria in spite of

plausibility.”