Proposal (1048) to South American Classification Committee

Revise

species limits in Habia rubica: A. Treat Middle American H.

rubicoides as a separate species; and B. Also treat Amazonian rhodinolaema group as a separate species.

Note from Remsen: This

is a proposal submitted to NACC (as “Treat

Red-crowned Ant-Tanager Habia rubica as six or seven species“)

that I here modify for SACC. First, is

the text of the original proposal, left largely intact, including the emphasis

on Middle American taxa not directly relevant to SACC; you can skip big chunks

of this. Then, I included comments from

NACC members. Finally, I restructure the

proposal and voting along lines consistent with the NACC results and relevance

to SACC.

Background

The Red-crowned Ant Tanager Habia rubica (Cardinalidae) is a highly polytypic taxon with marked geographical variation; up to 14 subspecies have been recognized, most of which were

described based on variation in the hue and intensity of plumage color

(Hilty, 2011). Its current distribution ranges from

central Mexico to northeastern Argentina and southeastern Brazil and encompasses

regions with very different ecological conditions or separated by recognized

biogeographical barriers (Hilty, 2011).

Ridgway (1902) placed Habia rubica in the tanagers, which

included 21 genera. One of them was Phoenicothraupis

(Cabanis 1850). According to

Ridgway (1902), the genus Phoenicothraupis

(described by Cabanis 1850 with the type Saltator rubicus Vieillot) had three species: Phoenicothraupis rubica

(with five subspecies: P. r. rubicoides, P. r. nelsoni, P. r. vinacea, P. r. affinis, P. r. rosea),

Phoenicothraupis salvini (with five

subspecies), and Phoenicothraupis

fuscicauda (monotypic). Ridgway (1902) described the genus Phoenicothraupis as follows:

Medium-sized

Tanagers superficially resembling the more uniformly colored species of Piranga, but outermost (ninth) primary

shorter than second (instead of decidedly longer than third); adult males with

a scarlet crown-patch and with more or less red on under parts (sometimes confined to the throat); females

and young brown

or olive above,

paler below. Bill as in the more slender-billed species of Piranga

but narrower (width at base scarcely if at all exceeding basal depth), the

gonys relatively shorter, and distinctly, though slightly, convex, and

maxillary tomium without any indication of a tooth-like projection. Nostrils

narrower. Rictal bristles strong, conspicuous, and frontal bristles (over

nostrils) well developed. Wing about three and three-fourths to a little more

than four times as long as tarsus, much rounded (seventh to fourth primaries

longest, ninth shorter than second); primaries exceeding secondaries by much

less than length of tarsus. Tail shorter than wing by much less than length of

tarsus, sometimes nearly as long as wing, more or less rounded, the rectrices

rather broad, with rather loose webs and somewhat pointed tips. Tarsus

decidedly longer than middle toe with claw; outer claw reaching about to or a little beyond

base of middle

claw, the inner

claw falling short of the latter; hind claw shorter

than its digit.

Coloration.—Adult

males reddish brown, reddish gray, or dusky, with bright red throat and crown,

the feathers of the latter

sometimes developed into a more or less obvious

crest; females and young usually brownish above, paler beneath, with or without

a yellowish-buffy or tawny

crown-patch; adult female

sometimes similar to the male,

but duller.

Range.—Southern

Mexico to southern Brazil, Paraguay, Bolivia, and western Ecuador.

Phoenicothraupis was placed in Habia by Hellmayr (1936) and subsequent classifications. The genus Habia was

until recently placed

in the Thraupidae, but we now treat

it in the Cardinalidae (Burns et al. 2014).

The

AOS currently treats

Habia rubica as single

species (AOU 1983,

AOU 1998). Hilty (2020)

recognized 17 subspecies as follows:

·

H. r. rubica: southeastern Brazil (southern Minas Gerais) to eastern Paraguay and

northeastern Argentina

·

H. r. bahiae: tropical

eastern Brazil (Bahia)

·

H. r. rubicoides: southern

Mexico (Puebla and eastern Veracruz)

to northern Nicaragua

·

H. r. holobrunnea: subtropical eastern Mexico (southern Tamaulipas to Veracruz and

northern Oaxaca)

·

H. r. nelsoni: southeastern Mexico (Yucatán Peninsula north of southern Campeche)

·

H. r. alfaroana: northwestern

Costa Rica (Guanacaste Peninsula)

·

H. r. vinacea: Pacific

slope of southwestern Costa Rica (Nicoya

Peninsula) to eastern Panama

·

H. r. affinis: Pacific slope

of southern Mexico (Oaxaca)

·

H. r. rosea: Pacific

slope of southwestern Mexico (Nayarit and Jalisco to Guerrero)

·

H. r. rubra: Trinidad

·

H. r. crissalis: coastal

mountains of northeastern Venezuela (Anzoátegui to Sucre)

·

H. r.

mesopotamia: Venezuela (Río Yuruán region of eastern Bolívar)

·

H. r. coccinea: eastern

base of eastern Andes of north-central Colombia

and western Venezuela

·

H. r. rhodinolaema: southeastern Colombia east of the Andes to northeastern Peru and far northwestern Brazil

·

H. r. peruviana: tropical

eastern Peru to central Bolivia

and adjacent western Brazil

·

H. r. hesterna River (eastward

to Rio Xingu), southward to northern Mato Grosso

·

H. r. perijana: Sierra de

Perijá (Colombia/Venezuela border)

New information:

Three recent studies were published on Habia rubica. One (Lavinia et al. 2015) was a phylogeographic

analysis that suggested that this species originated in South America, where

there are at least two clearly differentiated clades: one in the Atlantic

Forest of Brazil and another in the Amazon basin. However, limited

taxon-sampling precluded detailed

investigation of diversification

within Central America and southern Mexico. The other two studies (Ramirez-Barrera 2018, 2019) provided

new evidence, one using multilocus data and the other, plumage color.

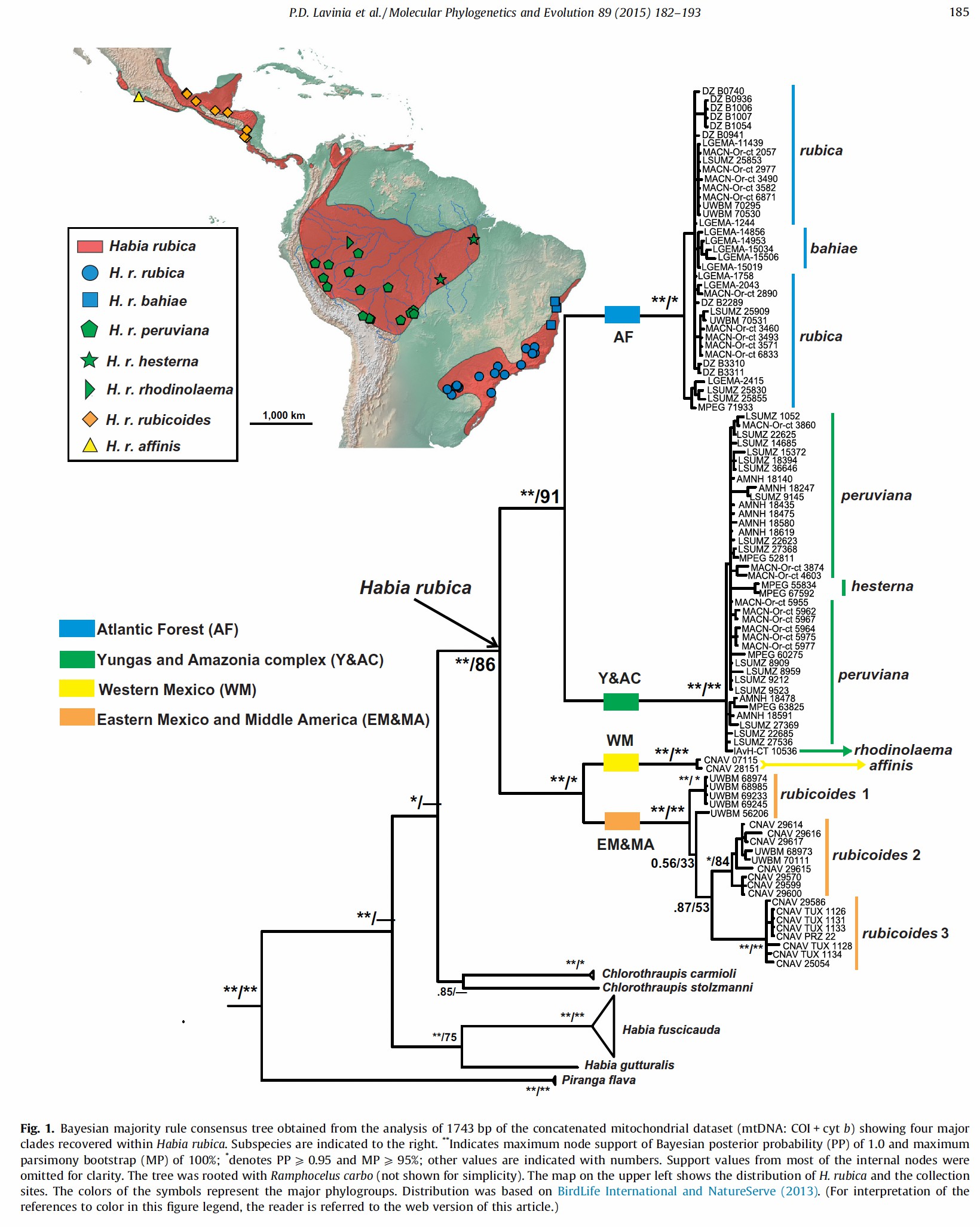

Lavinia et al. (2015) sequenced mtDNA and nDNA from 100

individuals from Mexico to Argentina. Their results are shown below (Bayesian

and maximum parsimony, Fig. 1). Their geographic sampling did not include Panama

and much of western Mexico.

The most important result was the identification

of two lineages in South American that split ca. 3.5 MA and two lineages in Middle America. Their analyses of

vocalizations and plumage coloration found differences between the four main

groups consistent with the molecular data.

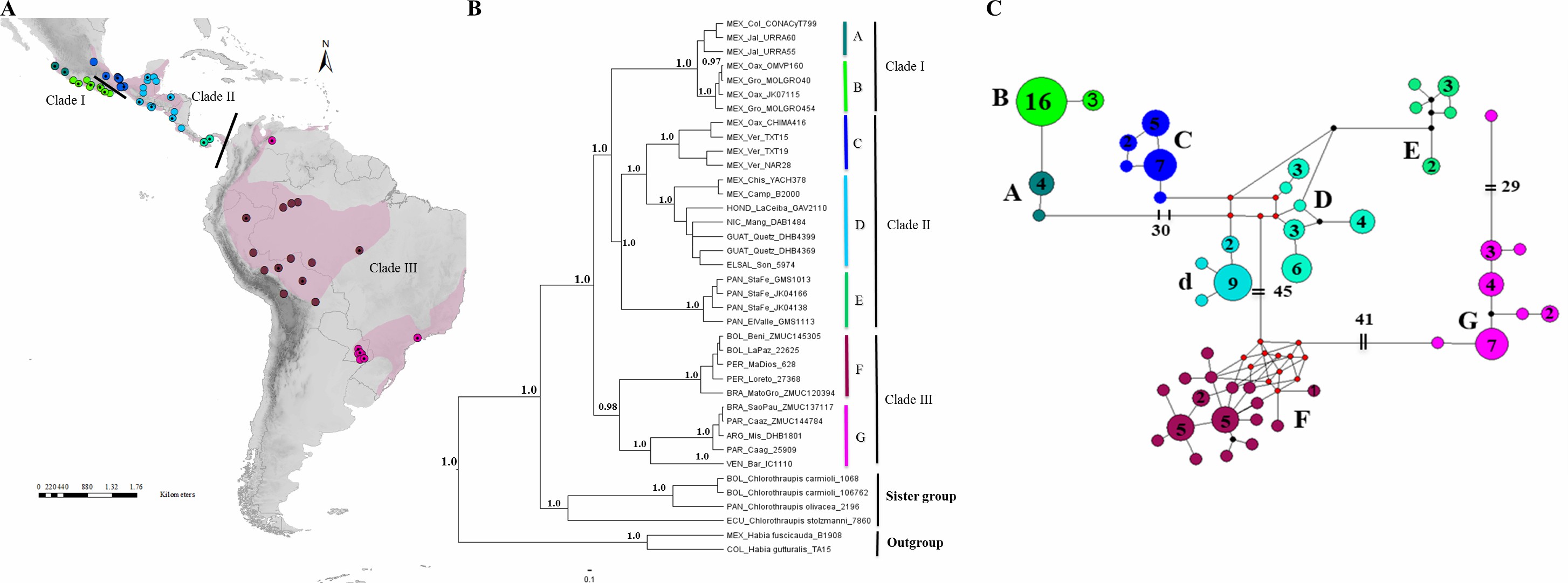

Ramirez-Barrera et al. (2018) amplified mitochondrial and

nuclear markers from 125 individuals of H.

rubica covering the species’ distribution, the other three species of Habia (fuscicauda, atrimaxillaris, gutturalis),

and 16 samples from Chlorothraupis (C. olivacea, C. carmioli and C. stolzmanni). They found that H. rubica can

be divided into three main clades: (1) western Mexico, (2) eastern Mexico to Panama, and (3) South

America. Within these

main clades they recognized

seven main phylogroups, as shown in the next figure:

Figure 1. Geographical

distribution, phylogenetic consensus tree, and haplotype network. (A)

Geographical distribution (indicated by pink shading) and sampling points of H. rubica; the mitochondrial DNA

sampling is represented by the color of the dots and the nuclear DNA sampling

is highlighted with a black dot on the dot’s color. ArcGIS (ArcMAP 10.2.2;

Esri, Redlands, CA, USA). (B) Phylogenetic consensus tree representing the relationship among populations of H. rubica, based on Bayesian inference

from a multilocus dataset. Values above branches denote posterior probabilities

(PP). (C) Haplotype network, where the phylogroup ”D'' corresponds to

individuals from the Chiapas-Yucatan peninsula to Costa Rica and “d''

corresponds to individuals from Guatemala and El Salvador

(the numbers inside

of circles indicate

the number of individuals

that shared each haplotype).

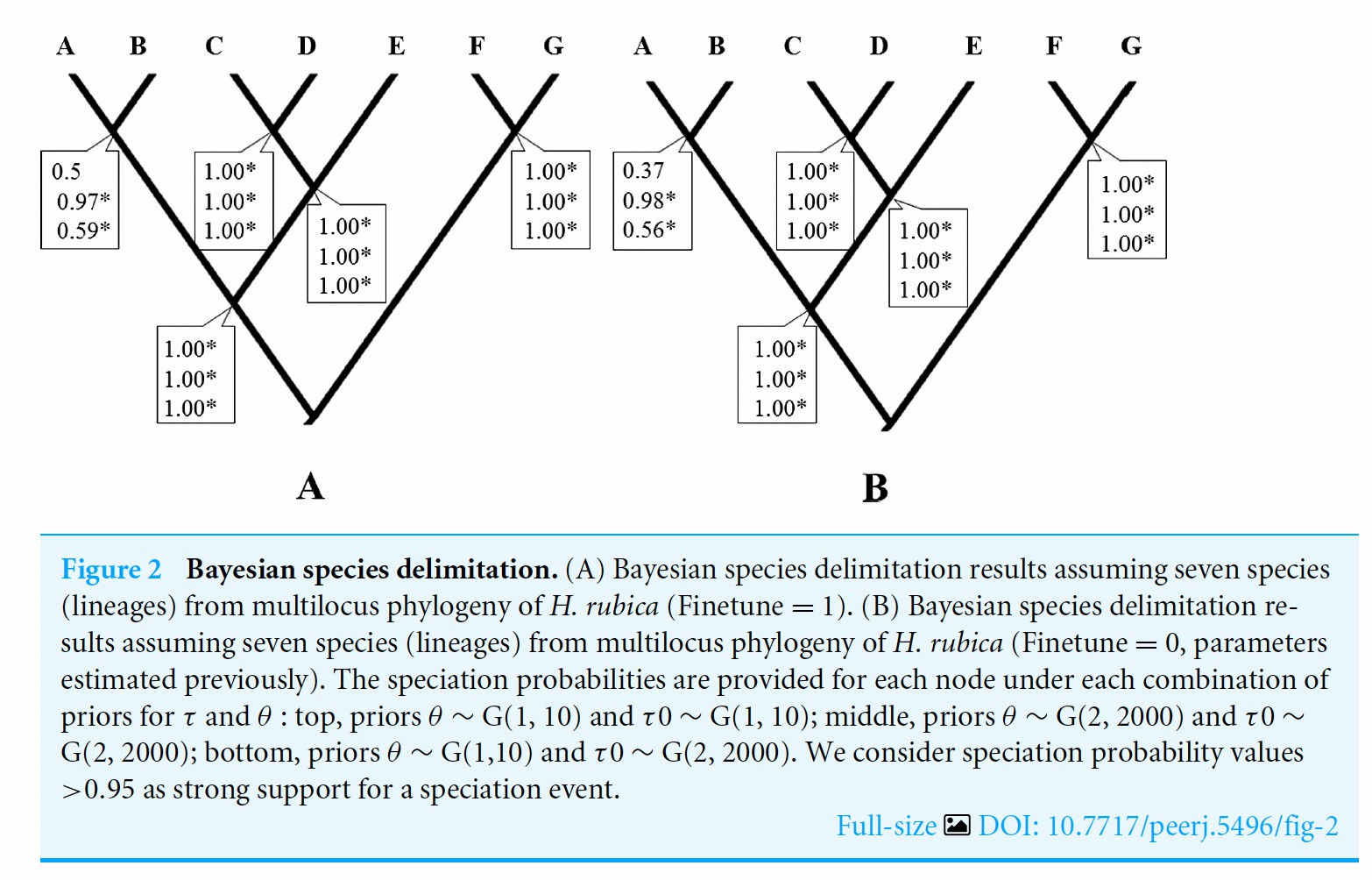

Ramirez-Barrera et al.’s (2018) species

delimitation analysis (BP&P) is shown on the following page; note the

high speciation probabilities (0.97 to 1.0).

![]() Ramírez-Barrera et al. (2019)

analyzed genetic, coloration, and morphometric data from specimens from

collections in Mexico and the United States and used the Multiple Matrix

Regression with Randomization (MMRR) approach to evaluate the influence of geographic

and environmental distances on genetic and phenotypic differentiation at both

the phylogroup and population levels. They found that geographic isolation was

the main factor structuring genetic variation within populations of Habia rubica; this suggests that climate

did not playing a major role in within-species genetic differentiation.

Ramírez-Barrera et al. (2019)

analyzed genetic, coloration, and morphometric data from specimens from

collections in Mexico and the United States and used the Multiple Matrix

Regression with Randomization (MMRR) approach to evaluate the influence of geographic

and environmental distances on genetic and phenotypic differentiation at both

the phylogroup and population levels. They found that geographic isolation was

the main factor structuring genetic variation within populations of Habia rubica; this suggests that climate

did not playing a major role in within-species genetic differentiation.

Recommendation:

We present two options:

(1)

Separate H. rubica into

seven species: This is based

on phylogenetic evidence and some differences on plumage color.

1.

Habia rosea (Nelson, 1898): Pacific coast of western

Mexico (Jalisco, Nayarit,

and Colima; lineage A in

Figure 2)

2.

Habia affinis

(Nelson, 1897): Pacific

coast of southwestern Mexico (Michoacan, Guerrero,

and Oaxaca; lineage B in Figure 2)

3.

Habia holobrunnea (Griscom, 1930): E Mexico from S Tamaulipas S to N Oaxaca (lineage

C in Figure 2

4.

Habia

rubicoides (Lafresnaye, 1844): S Mexico (from Puebla, E

Oaxaca, Tabasco, and Chiapas), Guatemala and Belize S to Honduras,

El Salvador, and Nicaragua (lineage

D in Figure 2).

5. Habia vinacea (Lawrence,

1867): Panama (lineage E in Figure 2)

6. Habia rhodinolaema (Salvin

and Godman, 1883): Amazon basin (lineage F in Figure 2)

7. Habia rubica (Vieillot, 1817): southeastern Brazil,

Argentina, and Paraguay

(lineage G in Figure 2)

(2) As

in Option 1 but treat lineages A and B as the same species (Habia rosea – Habia affinis). This option is to separate Habia rubica into six species based on two main arguments, the

first being the low speciation probability value (<0.95) presented by the

clade comprising the subspecies H. r.

rosea and H. r. affinis in the

BP&P analyses performed with multilocus data (Ramírez-Barrera et al. 2018).

The second argument is the consistency of this grouping through two independent

tests of the same analysis and with adjustment

of specific parameters. At the morphological level, both subspecies are described as a polytypic group characterized by

having paler plumage than the other subspecies of H. rubica (del Hoyo

2020). At the geographical level, the distribution of these two subspecies from

western Mexico is clearly delimited by three large mountain ranges: the Eje

Neovolcánico Transversal, the Sierra Madre del Sur, and the Sierra Madre

Oriental. These geographical formations seem to have great influence on the

genetic structure of the populations, acting as barriers to gene flow, which

has possibly promoted the differentiation between the populations of eastern

and western Mexico.

|

Species |

Proposal 1 |

Species |

Proposal 2 |

|

1 |

Habia rosea (Nelson, 1898) |

1 |

Habia affinis (Nelson, 1897) |

|

2 |

Habia affinis (Nelson, 1897) |

||

|

3 |

Habia holobrunnea Griscom, 1930 |

2 |

Habia holobrunnea Griscom, 1930 |

|

4 |

Habia rubicoides (Lafresnaye, 1844) |

3 |

Habia rubicoides (Lafresnaye, 1844) |

|

5 |

Habia vinacea (Lawrence, 1867) |

4 |

Habia vinacea (Lawrence, 1867) |

|

6 |

Habia rhodinolaema (Salvin and Godman, 1883) |

5 |

Habia rhodinolaema (Salvin and Godman, 1883) |

|

7 |

Habia rubica (Vieillot, 1817) |

6 |

Habia rubica (Vieillot, 1817) |

We recommend Option 1 for the following reasons:

1. The phylogenetic evidence

supporting the differentiation between H.

r. rhodinolaema and H. r. rubica in

South America is consistent across two independent studies (Lavinia et al.

2015, Ramírez-Barrera et al. 2018), which

present broad sampling

and cover most of the distribution

of both phylogroups. In addition, significant differences in traits such as

song and coloration have also been reported (Lavinia et al. 2015), which

support the probable differentiation between the two phylogroups. Furthermore,

there is a geographic correspondence between the distribution ranges of the

identified phylogroups (del Hoyo 2020), which could also indicate that

geographic barriers in South America have influenced their genetic

differentiation.

2. The deep genetic structure

reported between the phylogroups of Central America

and eastern Mexico

(Ramírez-Barrera et al. 2018) shows high support for the phylogenetic

hypothesis obtained with multilocus data. This genetic structure corresponds to

barriers to dispersal and gene flow such as the Talamanca Mountain Range in

Costa Rica, the Motagua-Polochic-Jocotán fault system, and the Isthmus of

Tehuantepec in southern Mexico, which could be promoting the reported genetic

isolation and genetic differentiation. Analyses of differences between these

groups for traits

such as song and coloration could not be tested in detail due to

the low sampling available; however, a clear difference is reported between

these phylogroups and the phylogroups distributed in South America (Lavinia et

al. 2015).

3. The five phylogroups distributed from central Mexico to South America show evidence of genetic and phenotypic differentiation,

as well as geographic correspondence in their distributions. We consider this

evidence sufficient to identify at least five clearly differentiated species.

This would allow us to better explain the relatively weak patterns of variation

among the subspecies described for this geographic range of H. rubica.

4. The phylogroups distributed

along the western slope of Mexico also show robust molecular differentiation

supported by a phylogenetic hypothesis based on multilocus data that shows a

profound divergence between those distributed in the north and south of this

region (Ramírez- Barrera et al. 2018). This evidence is supported by very

complete sampling, which covers the entire distributional range

of H. rubica and

leaves no room for doubt

about the genetic

structure of the species in

this region. In addition, there is evidence of geographic correspondence with

barriers such as the Transversal Neovolcanic Belt, the Sierra Madre del Sur,

and the Sierra Madre Oriental, which limit the distribution of populations and

have kept them isolated for long periods of time, which has favored the deep

genetic differentiation (Ramírez- Barrera et al. 2018). There is no evidence of

song differentiation as in the previous cases; however, both phylogroups are

recognized as a polytypic group whose coloration is markedly paler than that reported

in the rest of the species (del Hoyo 2020), which could add evidence

on the degree of differentiation that these groups present.

5. Habia rubica is

widely described as a polytypic species with a very wide distribution; however,

it has also been described as a species in which “differences between the

racial groups are not always clear-cut or pronounced” (del Hoyo 2020). “Several

of the numerous races are weakly differentiated and seem barely worth

recognizing” (del Hoyo 2020). This apparently weak phenotypic differentiation,

coupled with the complicated field identification of the different subspecies

(especially those with sympatric distribution), makes it necessary to consider

all those genetic, geographical, and phenotypic elements (e.g., pink coloration

of phylogroups from western

Mexico) as sufficient arguments to be able to recognize these

groups as independent species.

English names:

If the proposal passes, a follow-up proposal

on English names is needed.

We should also coordinate with SACC on this proposal.

Literature Cited:

Burns, K. J., A. J.

Shultz, P. O. Title, N. A. Mason, F. Keith Barker, J. Klicka, S. M. Lanyon, and

I. J. Lovette. 2014. Phylogenetics and diversification of tanagers (Passeriformes: Thraupidae), the largest radiation of Neotropical

songbirds. Molecular Phylogenetic and Evolution 75: 41-77.

Hilty, S. L.

2011. Family Thraupidae (Tanagers). Handbook of the birds

of the world. Tanagers to New World blackbirds, vol. 16.

Barcelona: Lynx Editions, 46 329.

Lavinia, P. D.,

P. Escalante, N. C. García, A. S. Barreira, N. Trujillo-Arias, P. L. Tubaro, K. Naoki

, C. Y. Miyaki, F. R. Santos,

and D. A. Lijtmaer. 2015. Continental-scale analysis reveals deep

diversification within the polytypic Red-crowned Ant Tanager (Habia rubica, Cardinalidae). Molecular

Phylogenetics and Evolution 89:182 193.

DOI 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.04.018

Ramírez-Barrera, S. M.,

B. E. Hernández-Baños, J. P. Jaramillo-Correa, and J. Klicka. 2018. Deep

divergence of Red-crowned Ant Tanager

(Habia rubica: Cardinalidae), a multilocus phylogenetic analysis with emphasis in

Mesoamerica. PeerJ. 1-19 DOI: 10.7717/peerj.5496

Ramírez-Barrera, S. M.,

J. A. Velasco, T. Orozco-Téllez, A. M. Vázquez-López and B. E. Hernández-Baños. 2019. What drives genetic and phenotypic divergence in the Red-crowned Ant Tanager (Habia rubica, Aves: Cardinalidae), a

polytypic species? Ecology and Evolution. DOI: 10.1002/ece3.5742

Ridgway, R. 1902. The birds of North and Middle America:

a descriptive catalogue of the higher groups, genera, species, and

subspecies of birds known to occur in North America, from the Arctic lands

to the Isthmus of Panama,

the West Indies

and other islands

of the Caribbean Sea, and

the Galapagos Archipelago. Bulletin of the United States National Museum No.

50, Part 2.

Blanca E. Hernández-Baños & Sandra M. Ramírez-Barrera, May 2025

Here

are the comments from NACC members (names removed to protect anonymity as per

NACC policy):

Voter 1: “YES to A. I find the combination of very old

(mid-Pliocene!) genetic lineages and qualitative differences in song and

plumage to be indicative of multiple species in the group. However, until

someone quantifies the differences in song and plumage, I am only comfortable

with recognizing three (and at most four) species in this group: the Atlantic

Forest, Amazonian, and Middle American lineages. There seem to be some

consistent differences with the two West Mexican lineages, and if other

committee members move towards recognizing that clade as a species, I am open

to the idea.

“So, for now, I will vote to

recognize as species the 3 clades listed above. The Lavinia et al. (2015) study

cited in the proposal does have some data on song and plumage, but they had

data mostly just for the Amazonian and Atlantic Forest clades, but they showed

that the latter has a darker / more saturated red plumage and a distinctly

slower song. The part that concerns me is that they mention that there was more

plumage variation within each clade than between. This agrees with my

experience with the species, which like many Cardinalids shows considerable

variation in the carotenoid-based colors, even within one flock. A thorough

study of plumage variation would be helpful, but even with those caveats in

mind, there are consistent differences between the clades in my experience. The

Atlantic Forest birds, in addition to being redder, are a distinctly intense

and evenly colored red that is quite different than that of the Amazonian and

Mesoamerican birds. The females are also distinctly brown (vs olive). There

also seem to be some qualitative structural differences with the Atlantic

Forest birds, especially in the head and bill shape. I was unfamiliar with the

song of this group, but in listening to recordings, they do have very widely

spaced notes, typically repeated, sound ‘clipped’, and are quite different than

the other clades. The calls also seem shorter. In contrast, the Amazonian birds

are somewhat paler red, more often have gray on the flanks, have a more

contrasting red throat, have clear whistled songs that are run together and

rise to a kind of crescendo at the end, and have longer harsher calls. The

Mesoamerican birds look to me more like the Amazonian group, but there is so

much plumage variation that I’m not sure if I can pick out a consistent difference

versus the Amazonian birds (a bit concerning). The Mesoamerican birds do have

distinctly rising notes that are given in pairs, at least in the north. The

southern Central American birds tend to have a kind of bouncy staccato song,

which likely warrants investigation. The ones in West Mexico are clearly pale

and small-billed, but again, there is much variation. The songs are more

slurred, too. These do seem to be allopatric from the populations in eastern

Mexico and are a distinct lineage on the tree.

“We will likely need another

proposal on English names if this passes, but I’ll just toss some ideas out

there. First, I don’t think that we should further modify “Red-crowned”, as

that will create unnecessarily long names. eBird/Clements has subspecies group

names, which are a good starting point, but do not perfectly match the clades

if we adopt fewer than five species. Given the brighter red plumage of nominate

H. rubica, I suggest following eBird/Clements’ and adopt Red Ant-Tanger

for this clade. For the other two, I suggest geographic or plumage-based

names. eBird/Clements uses Scarlet-throated Ant-Tanager for rubra

of the Amazon, which fits for the bird given its brighter throat, but could I

suppose cause a perceived association with Red-throated Ant-Tanager. Amazonian

Ant-Tanager could also work, but this species would also include the perijanus

of the Perijá mountain range (outside the Amazon). Regardless, both are SACC

issues. For our birds, eBird/Clements uses “Northern” for rubicoides of

Panama to east Mexico and “West Mexican” for the west Mexican clades. I suggest

Mesoamerican or Middle American Ant-Tanager for the combined group.”

Voter 2: “YES to A. As with other committee members, I

am most comfortable now with recognizing three species: Atlantic Forest,

Amazonia, and Middle America. The Lavinia et al. (2015) study had only one

sampling locality for western Mexico (n = 2), and that clade was also not

included in the vocal analysis. Furthermore, I am concerned by the lack of

study of any potential contact zone in Middle America; the only mention of a

contact zone there is the statement in the paper that “the possibility of a

contact zone in southern Oaxaca and Chiapas remains to be explored and

therefore the presence of gene flow cannot be fully discarded.” Until such a

study is done, I think it’s best to wait on splitting western Mexico

populations from those in eastern Mexico and Middle America.

Voter 3: “(A) YES; split the species; (B) Three species. I’ve

enjoyed reading the series of detailed papers on this complex; there are

definitely multiple species involved. There is good evidence for 5 or 6 species

under many concepts, such as the phylogenetic species concepts. However, since

we adhere to the biological concept, I think we need more evidence regarding

the proposed Mexico and Central American species, in particular vocal data. As

others have noted, to date we have song, plumage, and genetic data to justify a

three-way split (Atlantic Forest, Yungas & Amazonia, and Mexico/Middle

America). Thus, at this point, I would be in favor of voting for a 3-way

option. As a side note, one of my MS students has an unpublished MS thesis

(Scott 2019) with a UCE phylogeny that includes one sample each of these three,

and it shows the same set of relationships as the studies discussed in this

proposal. Levels of relative divergence is similar to divergence among

currently recognized species of other cardinals/grosbeaks.

Voter

4: “YES to a split. The

proposal and the papers it is based on make it clear that at least three BSC

species are involved. I also consider that the evidence favors treating the two

West Mexican taxa as a separate species (affinis) rather than as a

subspecies of rubicoides, based on the genetics, morphology, and song.

Song.---I downloaded and compared

songs of the two groups in sonogram composites, and it seems pretty clear that

the notes of affinis songs are more modulated and more vertical, while

the notes of rubicoides are more prolonged and horizontal, and often

with multiple note types per strophe rather than a single note type or a tiny

grace note as is typical of affinis. It also seems that affinis may

not sing that often, with many more recordings of calls than song, while there

are plenty of songs of rubicoides. Calls of these two groups are less

tractable, with multiple call types represented, some perhaps misidentified

(?), and not differing obviously in quick comparisons. (If anyone wants to see

the sonogram composites I’d be happy to share).

Plumage.---Not necessarily a species characteristic, but I

was quite impressed with the pallid plumage of birds I saw in Jalisco last

year, which seemed very unlike those I’ve seen elsewhere.

Genetics.---The two phylogenies presented in the proposal

show a divergence between the west Mexican and east Mexican/Central American

taxa more or less on a par with the other clades.

Distribution.---It’s not clear from either the range maps in

Howell and Webb, or eBird records, that there even is a zone of overlap between

the affinis and rubicoides groups. There seems to be a small

break in Oaxaca between the northern Oaxaca rubicoides group and

southern Oaxaca affinis group.

“So, I’m voting for four

species (first choice) and failing that, three species (second choice).

Voter 5: “YES. As other committee members have already

commented, I am only comfortable accepting a 3-species split, recognizing

Middle American, Amazonian, and Atlantic Forest birds as separate, although I

too would be open to also recognizing the West Mexican subspecies as separate

if the rest of the committee feels that is appropriate.”

Voter 6: “YES. I agree with the other committee

members that there is good evidence for a 3-way split of Middle American,

Amazonian, and Atlantic Forest birds. There may very well be additional splits,

but I’d like to see more analyses of phenotypic variation and putative contact

zones among the Middle American taxa. BP&P analyses certainly have value

but tend to oversplit lineages compared to more conventional species

delimitation approaches.”

Explanation

of SACC voting procedure from Remsen: As a consequence of these comments and votes,

NACC voted to recognize three species, as follows:

1. Habia rubicoides

(extralimital to SACC): includes all Middle American taxa listed in the

proposal, from Mexico to Panama.

2. Habia rhodinolaema: Amazonia etc. (includes peruviana and hesterna by genetic sampling and perijana, rubra, crissalis, mesopotamia, and coccinea by phenotype; note that rhodinolaema was not genetically sampled)

3. Habia rubica: Atlantic

forest (including bahiae)

Note

that the NACC proposal really didn’t get into the details of the South American

taxa – the focus was on Middle America.

So, let’s try this as a voting structure, with two YES/NO choices.

A. TWO SPECIES. YES is

to treat Middle American H. rubicoides as a separate species from all

South American taxa, i.e. treat the rhodinolaema and rubica groups as a single species, at least for

now. NO is for continuing the status quo, i.e., all one species. A NO vote on this automatically translates to

a NO on B (I think).

B. THREE SPECIES. YES is to treat all three

groups as separate species, as per NACC voting results. NO is for continuing the status quo, i.e.,

all one species, or for more than two species in South America (an option not

considered in the NACC proposal).

Note

from Remsen on English names: A separate proposal will be needed on English

names if either part of the taxonomic proposal passes, but meanwhile note

discussion in NACC comments.

Voting Chart: https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart1044+.htm

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“NO. I think the level of discussion for South American-Panamanian forms in the

current proposal is not sufficient to make an informed choice. The three

proposed species are clearly divergent in mitochondrial DNA, but the level of

nuclear divergence is difficult to tell because the concatenated mtDNA-nuclear

tree could be driven by mitochondrial divergence. Plumage differences, however,

are consistent with the subspecies level.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“YES to A and B. For A, this definitely shifts the burden of proof onto those

recommending the status quo. B is a well-substantiated spilt based genetic and

vocal evidence as well as more subtle differences in plumage. The split also

makes biogeographic sense because the two populations are rather widely

allopatric, following an Amazonia vs. eastern Brazil separation seen in many

other groups.”

Comments

from Areta:

“Well, as routinely happens, the lack of a paper

focusing on species-limits issues integrating data and a proliferation of

papers lacking complete taxon sampling creates a situation in which some things

appear to be obvious, some appear to be likely correct, and some other issues

go undetected or at least are not given the foreground place that they deserve.

I find it highly intriguing that none of the papers, nor the proposal, have

cited Parkes (1969), which is a highly relevant paper discussing important specimens

(e.g., the distribution of rhodinolaema

and coccinea, and the birds west of

the Andes in Colombia) and characterising two new subspecies from Venezuela (crissalis and mesopotamia).”

“Clade III in Ramírez-Barrera et al. 2018 is the South American clade, which is

deeply diverged from Clades I and II in Mesoamerica that should be the focus of

our deliberations. The deep split between these taxa was also recovered by

Lavinia et al. (2015). Thus, it is clear that there are two very deeply

diverged main lineages, one in South America and the other one in Mesoamerica.

mtDNA and concatenated mt+nucDNA are concordant.

“Lavinia et al. (2015) made the following taxonomic

recommendations:

‘ 4.5.

Taxonomic implications

We found H.

rubica to be monophyletic within our dataset with high support in spite of

the deep divergences among its main lineages. The Crested Ant Tanager (H.

cristata), a species that has not yet been included in any molecular

studies and that based on morphological and behavioral evidence seems to be

closely related to H. rubica (Willis, 1972),

should be included in future analyses to confirm this result. In addition, and

as evidenced by Klicka et

al. (2007) and Barker et al. (2015), H. rubica appeared more closely

related to species of the genus Chlorothraupis than to its congeneric

species, making the genus Habia paraphyletic as currently defined. Since

further analyses including H. cristata are needed to definitely

establish the phylogenetic affinities among the species of these two genera, we

are anyway keeping the genus name Habia for the new species suggested

below.

“Based on

consistent genetic, morphological and behavioral evidence, we believe that

splitting H. rubica into three species is the most reasonable and

conservative alternative for the moment. One of the species should be the

lineage present in the Atlantic Forest, which should keep the name H. rubica.

Despite the fact that our genetic analyses do not distinguish between the

subspecies rubica and bahiae from the Atlantic Forest, we believe

that further morphological and behavioral objective analyses (like the ones

performed here among main lineages) are needed to fully address their validity.

Therefore, we propose that this species should keep the subspecies rubica

and bahiae for the moment. Although we lack representatives of some

races distributed north of the Amazon River, we recommend that all South

American subspecies other than the ones from the Atlantic Forest are included

in a new species called H. rubra (given its taxonomic priority). Until a

more comprehensive sampling of the subspecies from northern South America

allows further genotypic and phenotypic analyses of this group, H. rubra

would include the subspecies rubra, peruviana, rhodinolaema,

hesterna, perijana, coccinea, crissalis, and mesopotamia.

Finally, we suggest considering the Mexican and Middle American lineage a

single species named H. rubicoides. This species would temporally

comprise the subspecies rubicoides and affinis, as treated by Navarro-Sigüenza and Peterson (2004), and alfaroana and vinacea,

until further sampling in western Mexico and southern Middle America allows a

deeper analysis of these subspecies."

“The deepest splits in Clade III are group F (which we can call

the rhodinolaema complex) and group G

(which we can call the rubica AND rubra complexes).

“The rhodinolaema complex: taxon rhodinolaema was apparently sampled by

Lavinia et al. (2015) but not by Ramírez-Barrera et al. (2018) (or so I

understand; it is tough to check all the samples for ssp. assignation, which

would have ideally been done by the authors; maybe it was sampled only for

mtDNA?), so its recognition would rest on the sampling of rhodinolaema, hesterna,

and peruviana (i.e., all its

constituent taxa).

“The rubica

complex: a tight grouping of AF birds, coupled to vocal distinctions

indicate that it deserves to be ranked as a species different from rhodinolaema.

This would include ssp. rubica and bahiae, both genetically sampled.

The rubra

complex: this group was not recognised as such by any of the published

papers or proposals, but I think that it can be reasonable to propose its

existence. One sample from the eastern base of the Andes of Venezuela (coccinea) is eye-catching, as it is

recovered as part of III-G, but it could as well have been placed on its own

"lettered" clade given the depth of the divergence and the

biogeographically implausible case of a species having a disjunct

distributional pattern in the E Andes of Venezuela and Colombia and in the

Atlantic Forest (see map in Ramírez-Barrera et al. 2019, which makes this more

evident). This Atlantic Forest/northern South America connection is in need of more attention. Interestingly, the subspecies rubra from Trinidad and crissalis, from the NE mountains of

Venezuela (Paria and Turimiquire; type from "Mirasol (3,000 feet), about

15 km. S. of Cumanacoa, Sucre, Venezuela") have very similar "double-

or triple-ticking" calls to coccinea

and perijana (https://search.macaulaylibrary.org/catalog?taxonCode=rcatan1&mediaType=audio&sort=rating_rank_desc&view=list®ionCode=VE),

and very unlike the harsh long rasp of Atlantic Forest birds or the dry, short,

staccato calls of the rhodinolaema

complex. Taxon rubra, the second

oldest name for Habia rubica sensu

lato, from Trinidad is also missing genetic data. Populations west of the Andes

in Colombia seem to also belong to this group and lack a name (if one is

needed; see Parkes 1969). Finally, the taxon mesopotamia from SE Venezuela (E Bolivar) also lacks samples (both,

vocal and genetic) and it was not even mapped by Lavinia et al. 2015 or

Ramírez-Barrera et al. 2018, 2019). So, we lack sampling of key subspecies

level entities that would presumably occur within the Clade III.

“I think it is troublesome to place the northern

Andes/Paria-Turimiquire/E Bolivar taxa in the same species with the Atlantic

Forest birds, when the admittedly meager genetic and vocal data indicate that

they are deeply diverged and vocally distinctive (as in the proposal). I

likewise think it is problematic to mix the rubra

and rhodinolaema complexes under an

enlarged H. rubra as in Lavinia et

al. 2015 (i.e., include every South American taxon here, except for H. rubica rubica and H. rubica bahiae).

“It seems that there are AT LEAST 2 species in clade G rubica (with rubica and bahiae) and rubra (including, it seems, rubra,

crissalis, coccinea, and perijana,

and one could stretch this to include mesopotamia).

This is a classic problem: whether we should follow our gut feeling, experience,

and sense of likelihood, or whether we should wait for solid data. I tend to

follow the latter approach, because this is how solid knowledge is built. So

far, I have proposed a different taxonomic hypothesis to those presented in the

proposal or by Lavinia et al. 2015, but to me this hypothesis has not been

rigorously tested. This group is still begging for a taxonomically minded

genetic work, and for more sound recordings.

“After writing all this, I´ve found that eBird has a "rubra" group, that includes what I

have here termed rhodinolaema and rubra complexes. These two are better

treated separately, based on the single genetic sample from Barinas of coccinea in Ramírez-Barrera et al. (2018)

and on the vocal differences of perijana,

coccinea, crissalis, rubra (and

maybe also the unrecorded, at least on XC and ML, mesopotamia) from the rhodinolaema

complex.

“What to do? There are hundreds of sound recordings that are crying to be

analysed. In a rapid assessment, it seems that they can help diagnose at least

3 main vocal (call) groups in Clade III which agree with genetic data (but many

ssp. need more vocal samples, some remain unrecorded, and some are lacking

genetic data). So, I think that

Clade III might better be treated as at least 3 species: rubica (with ssp. rubica

and bahiae), rhodinolaema (with ssp. rhodinolaema,

hesterna, and peruviana), and rubra

(with ssp. rubra, coccinea, birds W of the Andes in

Colombia?, and perijana, and perhaps

even mesopotamia, although this one

might as well be something different, and the composition of this third species

remains speculative).

Other scenarios are likely as well, one species could be Andean (coccinea and perijana), one limited to NE Venezuela (rubra) and another one to E Venezuela (and Brazil? Guyana?; mesopotamia). I think that the 3-species

solution might eventually be correct, but do we have enough data to decide?

What to do? Move forward piecemeal or wait for an integrative approach? I look

forward to the thoughts of others, knowing that I am usually on the "wait

for thorough data" team.

“Disclaimer: it seems to me that there are numerous situations here that should

be properly sorted in a rigorous taxonomic work. I approached this with an

inquisitive mind, and I think that I could grasp part of the complexity of the

situation. However, revising type (and other) specimens, assessing the

distributions of taxa, properly sampling for genetic data, and studying the

vocalizations should be done with greater attention to detail than what I could

afford to vote here. Yet, I think that I have uncovered a novel pattern that

should be tested. Maybe I erred here and there, but I feel that the overall

picture is accurate, and so here it is to be subjected to scrutiny and

criticism.”

Comments

from Lane:

“NO for now. As Nacho points out, it seems the original proposal did a

disservice in its layout of the clades and the proper use of nomenclatural

priority. I have not had the luxury of time and access to the LSU collection to

review and think about this properly, and so I will take the coward’s way out

and wait until I can give this case more study before I vote for change.”

Comments

from Naka:

“In light of the info provided I agree with a novel treatment within Habia.

“A. YES, I agree with

splitting the South American clades from the Middle American ones, which have

notable genetic and some morphological differences.

“B YES, I agree with

considering the two large clades in SA as distinct species, something that we

have done in the past within the Brazilian Committee. However, prior to making

this split, we need to properly define which name applies for the Amazonian

taxa. I am yet unconvinced that the name Habia rhodinolaema (Salvin and

Godman, 1883) applies for the entire clade.

“According to Lavinia

et al (2015) cited in this proposal: "we recommend that all South American

subspecies other than the ones from the Atlantic Forest are included in a new species

called H. rubra (given its taxonomic priority).", which is the

approach we took in Brazil a few years ago. If we are to use rhodinolaema,

we need to make sure this is the correct approach. But that seems to be a

technical issue that can be solved once the decision is made.”

Comments

from Claramunt:

“A reluctant YES to both A and B. The tree groups are clearly delineated

genetically but the phenotypic evidence is blurrier in the papers and in the

proposal. What are the phenotypic traits that would diagnose the three clades?”

Additional

comments from Stiles:

“B. still YES (the nomenclature can be settled later, as per Nacho).”

Comments

from Robbins:

“YES. When this proposal was first posted I spent some time and concluded that

I needed to revisit, which I have just done. Germane to our committee, Nacho

has delineated issues that need to be addressed. Nonetheless, based primarily

on the genetic data, I think it is reasonable at this point in time to

recognize at least three species: Middle American (likely more than one

species) and at least two species in South America. So, I vote YES to both A

& B.”

Comments

from Remsen:

“NO to A and B. I have no doubt that

additional data will continue to show that more than one species is involved,

but there are just too many unknowns.

“This

complex contains 17 recognized subspecies taxa, and the initial proposal

recommended dividing these into 7 species.

Vocal data have not been formally analyzed. Plumage data are essentially irrelevant to

species rank unless populations are in direct contact (at which point they may

serve as proxies for gene flow) or unless there is evidence that they are used

in mate choice. As noted by Elisa, nDNA or genomic data are absent except for a

UCE data-set involving a couple of taxa in an unpublished thesis (see Burns’

NACC comments), but even if they were available, I don’t think they are

relevant for assigning species rank unless taxa are in direct contact or unless

they are completely beyond anything known for taxa ranked as conspecific. The 3.5 mya divergence time is well within

the range of numerous sedentary tropical taxa treated at the subspecies rank,

so cannot be used as a reason for assigning species rank. I look forward to the day when decisions on

species-level taxonomy based solely on gene trees using neutral loci are no

longer considered valid.

“I

strongly support Nacho’s philosophy on this.

It feels sometimes as if we are rushing to make some splits when we know

more than one species is involved, or our gut tells us that additional data

will support preliminary qualitative information. What’s the rush? Unless there is an urgent conservation issue,

I see no reason not to wait for more rigorous, complete analyses on such a

widespread complex for which vocal and genetic data are or soon will be

available.”

“If

I were to undertake a study of this complex, the first thing I would do is

assemble a list of the 17 available names and their type localities. Then, I would assess whether these 17 names

refer to phenotypes that can be diagnosed by plumage; I think one could get

away with a semi-qualitative analysis in most cases. Habia rubica specimens are common in

collections. Borderline situations might

require quantitative analysis. This

would give you a list a valid taxa that should be

sampled. Then, I would assess whether any of these taxa are clearly parapatric;

if so, then an absence of intermediate phenotypes at the contact zones is

sufficient, in my opinion, for assigning species rank; this would put

burden-of-proof on treating them as conspecific. Then, I would see what is

available in terms of genetic and samples of presumed homologous vocalizations

that can be definitely assigned to a taxon based on proximity to type

localities. Lavinia et al. and Ramírez-Barrera et al. provide great assistance

in all this. Then, I would proceed with quantitative analyses of those data,

with careful attention to diverse geographic sampling especially proximity to

contact zones if they exist.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“A & B) “YES and YES. This is an

incredibly complex and case, given the number of named taxa involved, the

geographic span (Mexico to NE Argentina & SE Brazil), the gaps in taxon

sampling, and the lack of any quantified vocal analyses. Add to that, the lack of analyzed topotypical

material (genetic, vocal, phenotypic) means that we don’t even know how many

named taxa are even valid, leading to additional nomenclatural uncertainty as

to how to recognize clades identified by the genetic studies. In spite of all of that, I think it is

undeniable that the status quo of 1 species, is incorrect. I think the genetic data make clear that

there are at least 3 species here (Don’t forget that the original NACC Proposal

was for a choice between recognizing 7 species or 6, and everyone seemed to

vote “YES” but then proposed recognizing some different number of species.),

and the proposed breakdown of Middle/Central American, Atlantic Forest, and

everything else, while almost certainly oversimplified in my view, at least

represents an advance from the single species treatment that ‘moves the ball

down the field’. Further work will

likely result in a more granular subdivision of the Middle American and the

Andean/Amazonian/Guianan/northern Venezuelan clades, but I think what we

already know of genetic, vocal and phenotypic differences is sufficient to

split both the Middle American and Atlantic Forest taxa from one another and

from everything else. I have a fair

amount of field experience with Middle American taxa and with South American

taxa from outside of Brazil, but setting that aside, and looking at Part B of

this Proposal solely from a Brazil-centric perspective, it makes total sense to

me that nominate rubica (with ssp. bahiae), would be treated as a

distinct species from all of the taxa found in Amazonian Brazil (hesperna, peruviana & rhodinolaema). Atlantic Forest birds (rubica & bahiae)

share 2 types of songs, one, a distinctively phrased song with a slow cadence,

which, in my experience, is mostly a “dawn song”; and the other, a faster,

run-together sequence that is more often given during the day, while family

groups are foraging together (often as nuclear members of

mixed-species-flocks), and which are typically interspersed with the calls. Neither the dawn song nor the other song is

close to songs from any of the populations in Amazonia, nor have I heard

anything similar from elsewhere (outside of Brazil) in South America, or, from

anywhere in Middle/Central America.

Also, calls of Atlantic Forest birds are audibly different from those of

Amazonian birds, and the calls, which in Habia are given more frequently

than the songs, are probably especially important in maintaining group cohesion

when moving through the forest understory.

As for plumage differences, I would argue that the differences between

Atlantic Forest birds and the most geographically proximate Amazonian taxon (hesperna), particularly as they relate to the female

plumage (see photos below), are at least as great as those between Middle/Central

American populations of rubica and sympatric H. fuscicauda. In sum, the current evidence, while painting

a very incomplete picture, and while inadequate in many respects, at least

allows us to advance our treatment of the Habia rubica complex beyond

the current status quo, and in doing so, should serve as a springboard for the

more integrated and thorough analysis that this complex requires.

“The

2 photos below are of specimens from the LACM collection:

Top

photo: Lateral view from L to R: 2 female hesperna

from R Tapajós, Pará, Brazil; 1 female nominate rubica from São Paulo,

Brazil; and 1 female bahiae from Alagoas, Brazil.

Bottom

photo: ventral view, from L to R: 2 females and 1 male of hesperna

from R Tapajós region, Pará, Brazil; 1 female and 1 male of nominate rubica

from São Paulo, Brazil; and 1 male and 1 female of bahiae from Alagoas,

Brazil.

Comments

from Niels Krabbe (guest voter):

“A:

YES Split C American from South American forms.

“B: YES Split the Atlantic rubica with bahiae from remaining

South American forms.

“Both

trees agree in the split between Central American and South American birds.

Within South America, the vocal differences mentioned by Kevin and the dark

bill and underparts shown on the photos convince me that a split of

southeastern birds (rubica with bahiae) is warranted. As Nacho

suggests in his detailed comments, there will likely be at least one more split

to come (rubra group from rhodinolaema group), but until then, rubra

of Trinidad has priority for the remaining South American forms.

“I

find it rather unsatisfactory that Scott et al. (2024) apparently did not

upload their sequences to GenBank (also SACC proposal 1007).”

Comments

from Areta:

“"NO. We need a full taxonomic work integrating genetic data (available

for the most part, with some key holes), biogeographic thinking, vocalizations,

nomenclatural matters, and plumage. Until then, we have suggestions of

different possible treatments that may, or may not, pass the test of time. At

present, as I argued, I am convinced that there are more species in South

America than originally envisioned in the proposal, and I laid out the

possibilities there. If someone is willing to undertake the comparative work to

refine species limits in a coherent framework and publish a scientific work,

I´d be happy to reconsider. Otherwise, our treatment would be the result of a

blend of data and serendipity, instead of the product of a rigorous

taxonomically-minded work produced to clarify species limits. Thus, with a

heavy heart, I vote NO to A and B."

Additional

comments from Niels Krabbe: “Following Nacho's (and Elisa's) argumentation, and

awaiting Chesser's new sequences to be uploaded to GenBank (Scott et al. 2024),

I change my vote to NO for both A and B.”