Proposal (1052) to South American Classification Committee

Revise species limits

in South American Bubo owls: (A) Maintain broadly defined B.

virginianus; (B) Treat magellanicus as a separate species from B.

virginianus; (C) Treat nigrescens as a separate species from North

American B. virginianus, irrespective of the former’s status with

respect to magellanicus; (D) Treat nigrescens a subspecies of B.

magellanicus; (E) Also treat B. nacurutu as a separate species from B.

virginianus, restricted to North and Middle America.

Background: Proposal 328 was a first attempt

laid out before SACC to change the taxonomy of Great Horned Owl (Bubo

virginianus) in splitting off the austral form B. (v.) magellanicus

as its own species. The complex had first been reviewed by Traylor (1958), who

laid out the distribution and known taxonomy of the South American populations,

with a northern Andean subspecies (nigrescens, type locality: “Cechce”

<sic: Ceche, Chimborazo; Paynter 1993>, Ecuador), a southern Andean and

Patagonian subspecies (magellanicus, type locality: Tierra del Fuego), a

lowland savanna subspecies (nacurutu, type locality: Paraguay; including

scotinus from Caicara, Río Orinoco, Venezuela, and elutus from

Lorica, Bolívar, Colombia), and a caatinga form (deserti from Salitres,

near Joazeiro, Bahia, Brazil). As Mark Robbins has laid out the situation of

the taxonomy of the group in the previous proposal, I won’t run over it much

further here. However, largely due to a set of confounding recordings by Ted

Parker from the northern Andes of Peru (Cerro Cruz Blanca, Piura) associated

with a specimen at LSU (LSUMZ 97577) that has been identified as “Bubo

virginianus nigrescens?” (see images), the SACC rejected the proposal at

the time. These recordings seemed to represent a population of Bubo in

the Andes of northern Peru that shared both “northern” and austral song types.

Since

then, multiple authorities have supported the split, including Clements

checklist (Clements et al 2025)—and by extension, eBird—, IOC checklist (Gill

et al. 2025). This split within the American Bubo has been proposed by

various authors due to the distinctive song and smaller size of the austral B.

(v.) magellanicus (e.g., Koenig et al. 1999, Jaramillo 2003, Pearman and

Areta 2020) in comparison to the geographically nearby lowland form B. v. nacurutu,

particularly because of no habitat or elevational overlap between the two

despite very close proximity in Argentina (see comments by Jaramillo in Prop

328).

The first publication on the genetics of the complex (Ostrow et al. 2023)

showed a deep branch between B. (v.) magellanicus (including samples

from as far north as the Andes of Peru) and the remainder of the B.

virginianus complex, though not without some messiness. So, it is time for

SACC to re-evaluate the situation.

Analysis: At the time that Mark

drew up Proposal 328, we had been stymied by the absence of better voice and

genetic specimen sampling along the northern Andes. Since that time, two papers

have reviewed both the vocalizations of the American Bubo (López-Lanús

2015) and the genetics (Ostrow et al. 2023). Both have supported the split of B.

magellanicus from B. virginianus but have not suggested any further

changes to the taxonomy within the latter. In addition, new recordings, from

Ecuador and Colombia, have been added to Macaulay Library (see below). I will

discuss the voice and the molecular studies separately below.

Voice: So, to assess is each of

these new papers. López-Lanús (2015) did an exhaustive analysis of the

vocalizations of all populations of the Bubo virginianus complex from

Alaska and Canada south to Tierra del Fuego using online sound archives

(Macaulay Library and Xeno-canto). He concluded that there were five song types

represented: (1) the widespread North American voice (hereafter called “virginianus”),

(2) the Patagonian magellanicus, (3) savana nacurutu, (4) northern

Andean nigrescens, and (5) also considered the Parker recordings

mentioned above to represent an undescribed sixth voice type (which he called

“Ñécu” and which he proposed to be an undescribed taxon). Interestingly, the virginianus

voice is very strongly conserved throughout North America and is diagnosably

different in pattern (sex for sex) from both nacurutu and nigrescens.

I should point out, that in López-Lanús’ study, the least-represented

population in the sound collections he checked was nigrescens with N=4.

Since that time, additional recordings have been archived, particularly in

Macaulay Library, and these are key to the situation with nigrescens and

magellanicus. Importantly, these recordings include several duets, which

apparently are the circumstance when nigrescens gives the puttering

series that Parker recorded in Piura and that is so similar to magellanicus.

These recordings of the puttering duet span the distribution of nigrescens

from the Eastern Andes of Colombia to Piura, Peru:

ML cuts of B. v. nigrescens giving

puttering notes like B. magellanicus: ML616192787 (Cundinamarca,

Colombia), ML307206661 (Azuay, Ecuador), ML582374191 (Cañar, Ecuador), ML573946951, ML617182690 (Pichincha, Ecuador), ML21879, ML21880, ML21890 (Piura, Peru). See map

figure.

It

is this song type that López-Lanús (2015) considered his “new” voice “Ñécu!”

Apparently, it is actually a representative song type over the entire

distribution of B. v. nigrescens, and this may require a new view on the

relationships of that taxon.

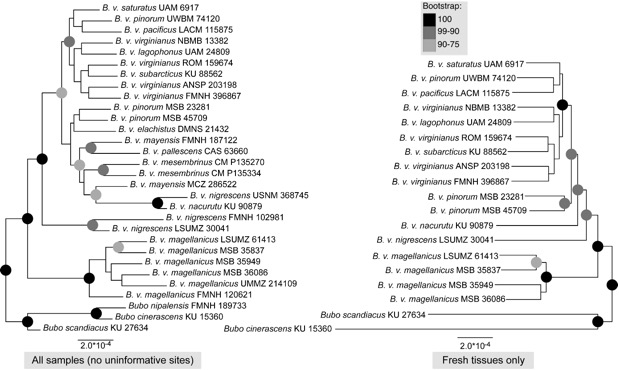

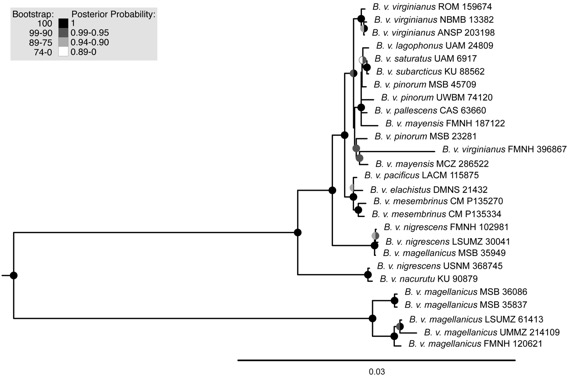

Genetic analysis: Ostrow et al.

(2023) used both nuclear UCEs and mtDNA over a large area of both the North and

South American distribution of the Bubo virginianus complex, although I

should note that North American samples greatly outnumbered South American;

some specimens were strictly sampled from toepads (including 2 nigrescens

and 2 magellanicus). The sample sizes of the South American taxa were

reported as: nigrescens 3, nacurutu 1, magellanicus 6.

However, I must point out that one of the “nigrescens” (a toepad sample)

was from La Guajira, Colombia, and therefore was actually a nacurutu.

This translates to an actual sample of nigrescens 2, nacurutu 2,

and magellanicus 6. In Ostrow et al. (2023), this misidentification

resulted in nigrescens being paraphyletic in their Figure 2 (all

samples) which is a maximum-likelihood UCE tree, with the La Guajira sample

being sister to the “single” nacurutu sample, although this now makes

sense as both samples were nacurutu.

I will point out that no southern nacurutu (which are closer to

the type locality) were sampled, so it would be useful to know how much

structure there is within the taxon, particularly between northern and southern

populations.

On

the “all samples” tree, the nacurutu branch comes out within the North

American virginianus group among samples that are largely from the

southwestern USA and Middle America. Sister to the North American/nacurutu

group is nigrescens, with magellanicus sister to this entire

clade. In the “fresh tissues only” tree of Figure 2, the North American clade

is sister to nacurutu (so: the two are monophyletic with respect to one

another) with nigrescens sister to them and magellanicus sister

to that entire clade. Figure 3 of Ostrow et al. is a maximum-likelihood tree

using mtDNA. This tree has the North American virginianus as a

monophyletic clade with its sister being nigrescens and a specimen of magellanicus

(from Lima, Peru). Sister to these clades is nacurutu (including the

misidentified “nigrescens”), and finally, the branch with the remainder

of magellanicus. Ostrow et al. (2023) concluded that there was still

gene flow between nigrescens and magellanicus (both Andean taxa)

in Peru, and also (some gene flow between one of the nigrescens (Cauca,

Colombia) and North American birds (!).

These genetic results have me

scratching my head a bit: the trees presented in the main paper of Ostrow et al.

(2023) seem not to have concordant branching among the North American birds, nacurutu,

and nigrescens, but all or the bulk of magellanicus is always

sister to that entire clade. But the positions of nacurutu and nigrescens

with respect to the North American birds switch depending on the tree, and a

Peruvian magellanicus is on the nigrescens branch on the mtDNA

maximum-likelihood tree. I can’t imagine that nigrescens and North

American birds are currently experiencing gene flow across the Darien (nor have

they in a long time!).

Recommendation: The publications since

Proposal 328 have made a bit of a hash of the distribution and taxonomy of the

complex, in part because of errors in assigning names to populations, in part

due to missing data that have since become available. The voice and phylogenetic

placement of B. magellanicus with respect to the rest of the B.

virginianus complex seems to make a strong argument that it should be

recognized as a separate species. However, there appears to be molecular

evidence of continuing gene flow between magellanicus and nigrescens

in Peru AND the vocal repertoire of nigrescens actually contains the

puttering component that makes magellanicus so distinctive as to result

in its split by so many authorities! So, if the gene flow between the two taxa

is real, why aren’t they on a single branch apart from the remainder of the

complex? Could it be a sampling artifact?. Finally, even though nacurutu

and nigrescens are both later branches off the main B. virginianus

tree with respect to B. magellanicus, each clade has distinctive voices

compared to the virginianus voice, and neither is actively experiencing

gene flow with populations of the North American virginianus group (the

separation between nigrescens and the nearest virginianus is

between the Central Andes of Colombia and Costa Rica, and similarly between nacurutu

in the lowlands of northern Antioquia, Colombia, and Costa Rica). My gut

feeling is that we should divide up the B. virginianus complex into four

species: B. virginianus (all taxa south to Panama), B. nacurutu

(lowlands of South America, including the populations named scotinus, elutus,

and deserti, the validity of which remain to be reviewed), B.

nigrescens (Andes of Colombia to Piura, Peru), and B. magellanicus.

Either this or continue to maintain the full group as one species, as it seems

that nigrescens and magellanicus share the “distinctive”

puttering that has been the main character used to separate the latter from the

remaining complex, and that Ostrow et al. found evidence of continuing gene

flow between the two in Peru. Comprehension of the molecular results of Ostrow

et al is not exactly in my wheelhouse, so I will leave it to those on the

committee who can address them better and how best to vote. So, these are the

options I see:

A.

Maintain Bubo virginianus with all of the South American populations

within it until their relationships are better understood (this seems the least

helpful, I recommend NO).

B.

Separate B. magellanicus from the remainder of B. virginianus

(this seems the favored stance by most other authors and lists, but leaves some

mess swept under the rug, I recommend YES).

C.

Separate nigrescens from North American B. virginianus,

irrespective of the former’s status with respect to magellanicus (vocal

and molecular datasets support this. I recommend YES).

D.

Consider nigrescens a subspecies of B. magellanicus (there is

evidence of some genetic flow between them, and vocally the two share the

puttering vocalization, but it seems to be given under different circumstances

within each. We don’t have much information on what sort of contact zone there

is between the two in Peru. Given that Ostrow et al. do not have any trees

showing nigrescens to be monophyletic with respect to magellanicus,

however, I think this may not be the right move. I weakly suggest NO).

E.

Also separate B. nacurutu from B. virginianus, now restricted to

North and Middle America (given the voice distinctions, especially compared to

the surprising conservativeness within North American populations, I am

inclined to recommend YES).

Literature

Cited

Clements, J. F., P. C.

Rasmussen, T. S. Schulenberg, M. J. Iliff, T. A. Fredericks, J. A. Gerbracht,

D. Lepage, A. Spencer, S. M. Billerman, B. L. Sullivan, M. Smith, and C. L.

Wood. 2024. The eBird/Clements checklist of Birds of the World: v2024.

Downloaded from https://www.birds.cornell.edu/clementschecklist/download/

Gill F, D Donsker &

P Rasmussen (Eds). 2025. IOC World Bird List (v15.1).

Jaramillo, A. 2003.

Birds of Chile. Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, New Jersey, USA

König, C., F. Weick,

and J-H. Becking. 1999. Owls. A guide to the owls of the world. Pica Press,

Sussex, England.

López-Lanús, B. 2015.

Análisis domparativo de las vocalizaciones de distintos taxa del género Bubo

en América. Hornero 30:69-88.

Paynter, R. A. 1993.

Ornithological Gazetteer of Ecuador, second edition. Museum of Comparative

Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

Ostrow, E. N., L. H. DeCicco, and R. G. Moyle. 2023.

Range-wide phylogenomics of the Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus)

reveals deep north-south divergence in northern Peru. PeerJ 11:e15787

http://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.15787

Pearman, M. and J. I.

Areta. 2020. Birds of Argentina. Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, New Jersey,

USA

Roesler, I. (2024).

Lesser Horned Owl (Bubo magellanicus), version 1.1. In Birds of the

World (S. M. Billerman and F. Medrano, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology,

Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.grhowl2.01.1

Schulenberg, T.S., D.

F. Stotz, D. F. Lane, J. P. O'Neill, and T. A. Parker, III. 2007. Birds of

Peru. Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, New Jersey, USA.

Traylor, M. A. 1958.

Variation in South American Great Horned Owls. Auk 75:143-149.

Dan Lane, May 2025

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Vote tracking chart:

https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart1044-.htm

Comments

from Stiles:

“A. NO. Clearly at least two species are well defined genetically, vocally and

phenotypically. B. YES: the easiest choice; magellanicus is clearly

separate from all the rest. C [now E]. YES to also splitting off nacurutu and

nigrescens as good species. In going over the distributions of all of

these taxa in several recent guides and other treatments, I was surprised at

the wide distribution of nacurutu, which extends from the entire

Caribbean region of NE Colombia through NC Colombia into NW to NE Venezuela,

and also extends through the entire region of the Llanos in both countries (if

nothing else, this form was severely under-sampled in the genetic studies). It

is nearly everywhere a lowland species (ca. 0-600m elevations, although it might

reach higher in extreme NE Venezuela). On the other hand, nigrescens is

entirely montane in its distribution in S Colombia in the Eastern and Central

Andes (and the Western Andes as well?) at elevations of 2500-4000m, south in

the Andes through Ecuador to NE Perú (and Bolivia?). This species is absent

from Venezuela, and there might be some overlap with the range of nacurutu in

Colombia but the two occupy widely different elevations (and given their

different ecologies, vocalizations and genetics, gene flow between them would

seem highly unlikely in the recent past).”

Comments

from Krabbe:

“My votes are:

A: NO

B:YES (split magellanicus from virginianus)

C: YES (split nigrescens from virginianus)

D: NO

E: YES (split nacurutu from virginianus).

“After

listening carefully through the vocal material, I must agree with Dan that the

Piura recordings (ML21879, ML21880, ML21890) are typical of nigrescens

in both hoots and the context of the puttering series. Recordings from

Cajamarca (XC139660) and Lima (ML54603211, XC215522) are like recordings of magellanicus

from Chile and Argentina.

“Besides

the Piura recordings, I thus concur with López-Lanús (2015) in that there are 4

vocal groups: virginianus, magellanicus, nigrescens and nacurutu.

As voice appears to be similar throughout the ranges of each group, it makes

sense to rank all four as biological species, which is also in general

agreement with the phylogenetic trees. Despite the mitochondrial tree

suggesting some gene flow between magellanicus and nigrescens,

the fresh tissue UCE tree places all four in separate branches.”

Comments from Areta: “The conflictive nigrescens (USNM 368745) from Guajira,

Colombia, that falls as sister to nacurutu

(KU 90879) in both the UCE and mtDNA trees in Ostrow et al. (2023) can be

explained away because this bird IS nacurutu

and not nigrescens (based on

geography, altitude, and habitat). Once this is accepted, then the only oddball

seems to be the placement of a magellanicus

sample from ‘Peru, Lima’ (MSB 35949; where exactly from?) as part of the nigrescens clade in the mtDNA tree,

while this sample is well embedded within the magellanicus clade in the UCE dataset. Whether this is true

mitonuclear discordance or there is some other explanation, I don´t know, but

at any rate, the UCE tree solidly places this bird in the magellanicus clade, which would seem to make the most sense

biogeographically (we also don´t know how this specimen looks).

“The differences in vocalizations between virginianus and nacurutu

are constant but I´d say not dramatic, and the same applies to vocalizations of

nigrescens and magellanicus. When taken in conjunction, the patterns of geographic

replacement/parapatry, the differences in plumage, phylogenetic relationships,

and vocalizations as described by López-Lanús (2015) and further clarified by

Dan, tip the scale towards the recognition of four species-level taxa. Much

remains to be done to clarify the extent (if any) of gene flow between the taxa

indicated in Ostrow et al. (2023), and whether past hybridization has played

any role in the vocal features found in nigrescens.

Its jumping phylogenetic position depending on the markers and samples

analysed, and the vocal features shared with magellanicus are intriguing, and this looks like an interesting

research question integrating fieldwork and genomics.

“A:

NO - It seems untenable to have a single species

“B:

YES (split magellanicus from virginianus)

“C:

YES (split nigrescens from virginianus)

“D:

NO - It is not such an easy call, but the phylogenetic trees have never

recovered nigrescens as more closely

related to magellanicus

“E:

YES (split nacurutu from virginianus)”

Comments

from Naka:

“I agree that genetics look messy, but I generally agree with the novel

proposal, as follows:

“A: NO, it's time to

deal with this species.

“B:YES (split magellanicus

from virginianus), easy.

“C: YES (split nigrescens

from virginianus)

“D: NO

“E: YES (split nacurutu

from virginianus), for now. I wonder if further splitting will be

necessary from tropical lowland South America.”

Comments

from Robbins:

“

“A. NO, clearly more

than one species is involved based on vocalizations and genetic data.

“B. YES for recognizing

magellanicus as a species based on voice and genetic data. Yes, the contact zone between it and nigrescens

as well as potentially magellanicus with southern nacurutu need

to be examined (in the development of the project, I pointed out to Ostrow that

several key samples should be incorporated in the study that ultimately

weren’t).

“C. YES for recognizing

nigrescens as a species despite sampling issues as mentioned above.

“D. NO, see comments

above.

“E. YES. I’m more on

the fence regarding this recommendation. Despite mislabeling (I pointed out to

Ostrow that La Guajira, Colombia sample was mis-labeled prior to publication),

much more genetic sampling of nacurutu (see my comments under B) is

needed throughout its range. Nonetheless, based on available vocal data it

appears nacurutu’s voice is consistently distinct from populations north

of South America. So, I support recognition of nacurutu as a species.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“A. NO. B.YES; C.YES; D. NO; E. YES.”

Comments

from Remsen:

“The vocal data are convincing to me that the best taxonomic assessment of this

complex is to treat them as at least three species. I am seriously concerned with the nagging

problems pointed out by Dan with respect to species rank for nigrescens

and I am tempted to vote against species rank for nigrescens until these

details are worked out. On the other

hand, if better sampling does suggest free gene flow between them, then we can

repeal the decision to treat them as separate species. The deciding factor to vote for separate

species rank is the point made by Dan in terms of the homogeneity in virginianus

vocalizations despite remarkable geographic variation in plumage and habitat,

so by a yardstick comparison, consistent vocal differences despite some shared

motifs argues for species rank. Therefore,

my votes conform to those of all voters so far: A. NO. B.YES; C.YES; D. NO; E.

YES.”

Additional

comments from Stiles:

“D. NO to considering nigrescens as a subspecies of magellanicus.

Data on genetics and ecology now available favor considering nigrescens

as a separate species.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“

“A. NO. Evidence for recognizing at least two species

within this complex is overwhelming.

“B. YES. As Gary says, this is an easy choice, based

upon genetic, phenetic and vocal differences.

“C. YES. The sharp break in vocal differences, along

with the molecular data supports this.

“D. NO. This one is the toughest call, given that the

two taxa share the distinctive “puttering” call, and that there is at least

some evidence for some gene flow, but, ultimately, I am persuaded that these

two are different beasts, by voice, plumage and ecology.

“E. YES. As noted by others, the vocal distinctions

between nacurutu and North/Central American virginianus are not

particularly impressive, but they are consistent, and when compared to the

conserved nature of vocalizations of virginianus throughout North &

Central America, I think this is enough to justify recognition as separate

species.”

Comments

from Claramunt:

“A. NO. Redundant

option.

“B. YES. This is

well-supported by vocal and genetic data.

“C. NO. Given the

modest differentiation in song and the ambiguous genetic data, I think it’s

better to keep nigrescens in the virginianus complex.

“D. NO. The genetic

data clearly show that nigrescens is closer to the main virginianus complex,

not to magellanicus. There may be some signal of ancestral gene flow

between nigrescens and magellanicus but seems minimal, if not

entirely artifactual. The sharing of “puttering” notes may be ancestral to the

group and not indicative of relationships.

“E. NO. There is not

much evidence that nacurutu has separated from virginianus genetically.

Plumage and song differences are subtle.”