Proposal (1055) to South American Classification Committee

Revise species limits

in Onychorhynchus coronatus.

Effect

on SACC:

This could split widespread Onychorhynchus coronatus into as many as six

species.

Background: Our current Note is

as follows:

2. Ridgway (1907), Cory & Hellmayr

(1927), and Pinto (1944) considered the four

subspecies groups in Onychorhynchus coronatus as separate

species: mexicanus of Middle America and northwestern Colombia, occidentalis

of western Ecuador and northwestern Peru, coronatus of Amazonia, and swainsoni

of southeastern Brazil. Meyer de Schauensee (1966, 1970) treated them all as

conspecific without providing justification, and this was followed by Traylor

(1977<?>, 1979b), AOU (1998), Sibley & Monroe (1990), Fitzpatrick

(2004), Ridgely & Tudor (1994), who provided rationale for their continued

treatment as conspecific, and Dickinson & Christidis (2014), but this was not

followed by Wetmore (1972), who considered the evidence insufficient for the

broad treatment. Ridgely & Greenfield (2001) and Hilty (2003) returned to

the classification of Cory & Hellmayr (1927). Collar et al. (1992)

considered occidentalis as a separate species. See Whittingham &

Williams (2000) for analysis and discussion of morphological characters. Del

Hoyo & Collar (2016) recognized four species: O. mexicanus of Middle

America and n. South America; O. occidentalis of the Tumbesian region; O.

coronatus of Amazonia; and O. swainsoni of the Atlantic Forest. Reyes et al. (2023) presented data relevant

to recognition of as many as six separate species based mainly on deep

divergence in mtDNA. SACC proposal badly needed.

Birds

of the World/Clements has instituted a 2-way split: https://ebird.org/species/royfly1

Ridgely

& Tudor (1994) thought that perhaps four species could be recognized, but

that treating them all as conspecific was the best course given similarities I

behavior and voice, as far as was known at the time. (They mistakenly cited AOU 1983 as having

recognized two species.)

Six

taxa are recognized in the complex (Dickinson & Christidis 2014):

• mexicanus (s. Mexico to Panama)

• fraterculus (n. Colombia and nw.

Venezuela

• occidentalis (Tumbesian region)

• coronatus (Guianan Shield and n. and

e. Amazonian Brazil)

• castelnaui (w. Amazonia)

• swainsoni (se. Brazil)

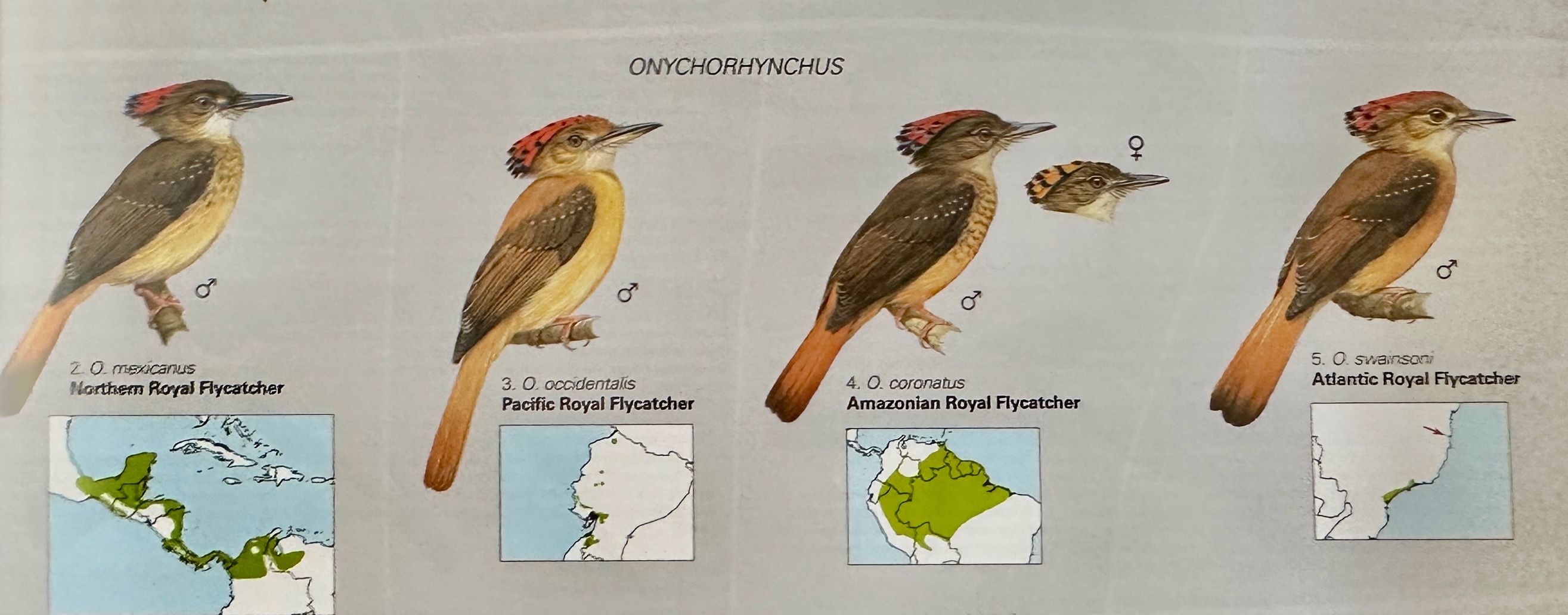

Here

are Hilary Burn’s illustrations from del Hoyo and Collar (2016), which

illustrate the differences in plumage, primarily in degree of markings on

breast and general plumage tone. Note

that swainsoni and geographically distant occidentalis are the palest

and least spotted of the group, and I suspect this is what influenced Meyer de

Schauensee’s reasoning for treating them all as conspecific.

In

Harvey et al.’s (2020) massive phylogenetic analysis of the suboscines using

genomic (UCE) data, 4 subspecies were included.

Swainsoni was “basal” to the other taxa, with an estimated

divergence time of ca. 6 MYA; nominate coronatus was the sister to mexicanus

+ occidentalis, with divergence estimate of ca. 3 and ca. 1 MYA,

respectively:

Just

eye-balling node depth in adjacent clades in the Harvey et al. tree indicates

that 6 MYA divergence is more typical for taxa treated at the species level,

whereas 3 and 1 MYA are more typical for taxa traditionally treated as conspecific. This is no substitute for a formal analysis

but is meant only to provide a crude comparison of node depths. Feel free to make your own comparisons, of

course.

New

information:

Reyes et al. (2023; note that the “et al.” includes our Luciano and Elisa)

produced the first genetic analysis of the complex. They used a single mtDNA marker: NADH. They sampled 40 individuals, including

individuals of all taxa in the complex.

They had only 1 swainsoni but had at least 5 for the other 5

taxa.

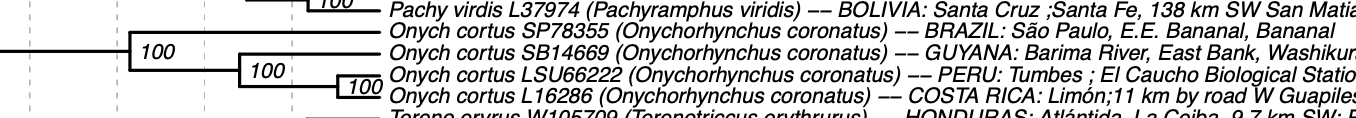

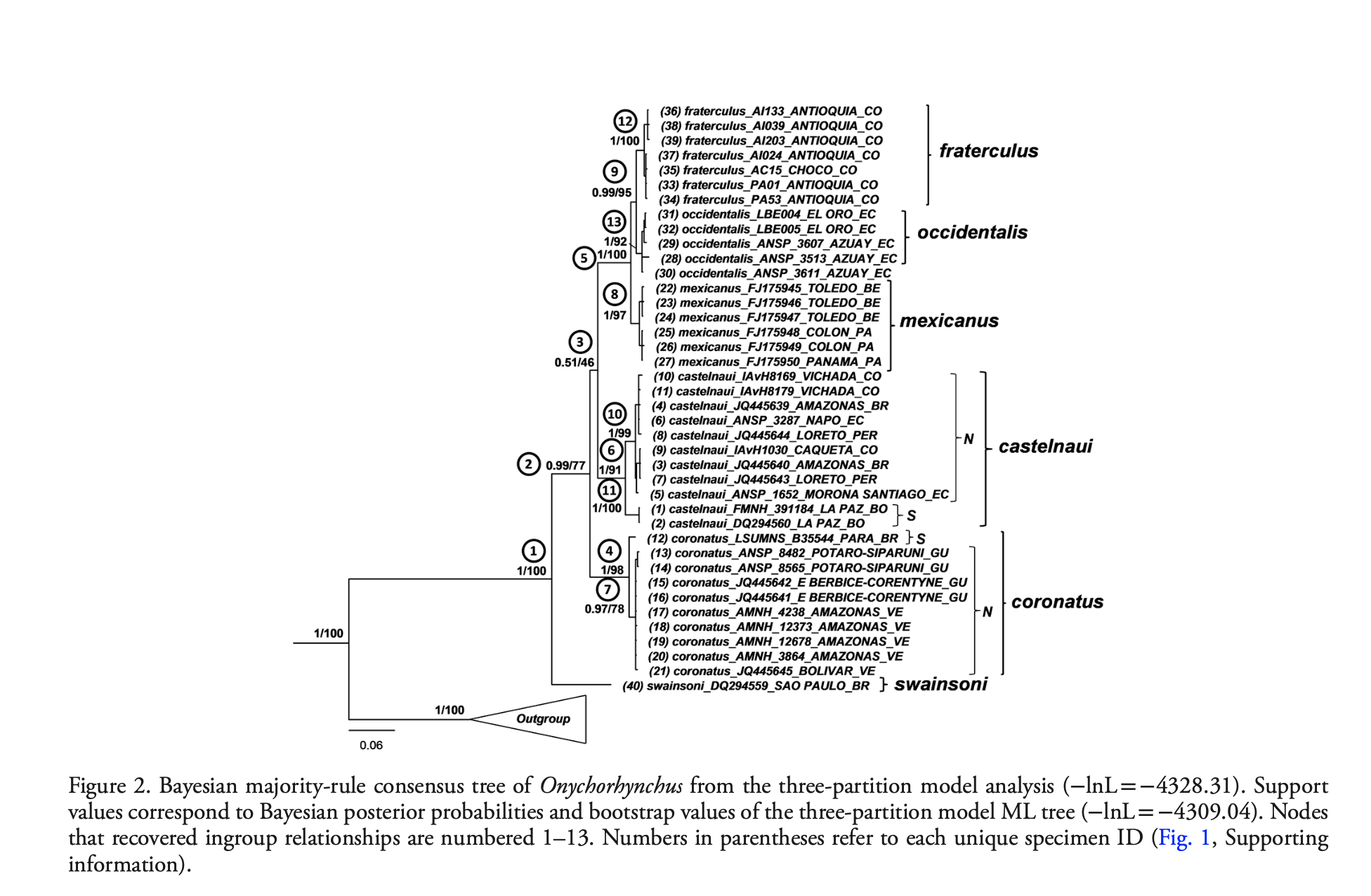

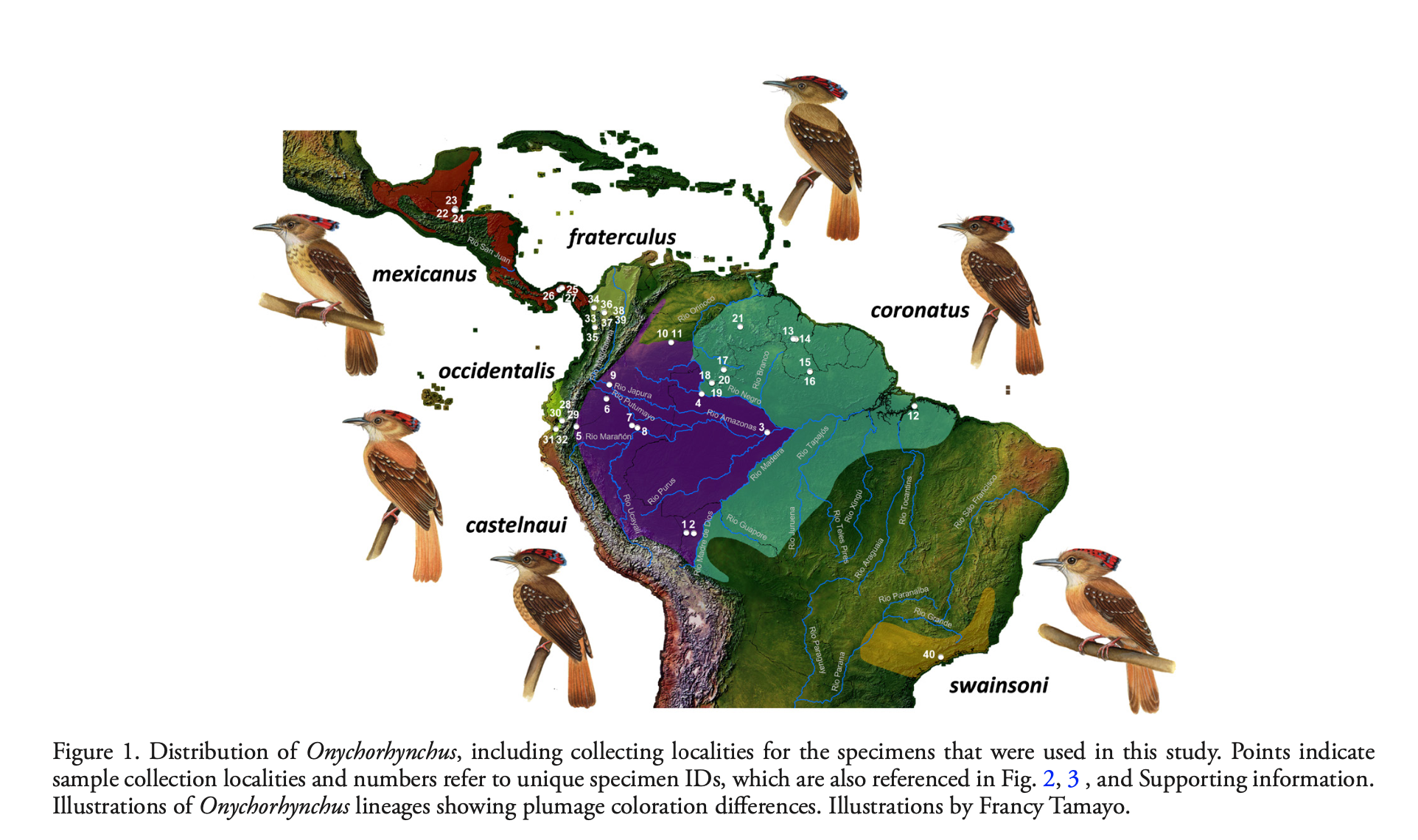

The

topology of the tree was consistent with that of Harvey et al. (2020),

including the placement of the taxon with arguably the most divergent plumage, occidentalis,

within the northern mexicanus group.

Their geographic sampling was reasonably thorough except for the absence

of specimens from the populations attributed to coronatus from Brazil

south of the Amazon and e. Bolivia:

The

mean estimate of the divergence time between swainsoni and the rest was

6.1 MYA, remarkably similar to that of Harvey et al. (2020). The focus of the paper was on historical

biogeography, not taxonomy, so the paper did not produce any firm taxonomic

recommendations. Nevertheless, their

analysis produced evidence for 6 independently evolving mtDNA lineages that

they suggested could be treated as species.

Caution is required because the geographic and numerical sampling is possibly

insufficient to be certain that the lineages are monophyletic, at least in

southwestern Amazonia, where large areas of coronatus distribution in

potential contact with castelnaui have not been sampled. Their

concluding paragraph is as follows:

“Furthermore,

this study helped to reveal independently evolving lineages that might have to

be treated as separate species with different conservation concerns.

Complementary studies that include nuclear DNA, morphology, niche

differentiation, and vocalizations with thorough sampling throughout the Onychorhynchus

distribution are needed to fully resolve the evolutionary relationships and

delimit species within this genus.”

Potential

changes in species limits are also implied in the section titled Cryptic

Diversity. I have to point out that the

diversity cannot be described as “cryptic” if it has been known for more than a

century with at least 4 taxa treated as separate species for the first half of

the 20th century, and the only taxon not described before 1860 was fraterculus

Bangs 1902. In fact, Reyes et al. make

this very point in that same section.

As

for vocalizations in this group, analyses are handicapped by how few samples

there are. Royal Flycatchers vocalize

infrequently, and dawn songs are poorly known.

Thus, It is no surprise to me that Peter Boesman did not include this

species as one of his 400+ “Ornithological Notes” (for HBW/BLI) despite this

complex being a prime candidate for a preliminary analysis.

Kirwan

et al. (2024a, b) summarized what is known about vocalizations in this group,

with links to recordings. In Birds of

the World, they are treated as two species: O. swainsoni for se. Brazil

and O. coronatus for everything else.

Kirwan et al. (2024b) outlined the differences used by del Hoyo &

Collar’s (2016) adoption of the Tobias et al. scoring system and said this

about voice: “Also distinctive in call, which is significantly shorter (effect size

4.9; score 2) and higher-pitched (effect size also 4.9; score 2) than that of

other taxa.” [It sounds lower-pitched to me.] Here are the

recordings cited by Kirwan et al. (2024b):

https://search.macaulaylibrary.org/catalog?taxonCode=royfly5&mediaType=audio&sort=rating_rank_desc

Kirwan

et al. (2024a) described the vocalizations of the coronatus group as

follows:

“Song. A

rarely heard series of whistles, which apparently varies geographically. There

are however hardly any recordings available, thus the following are merely

examples of specific cases:

· Northern

group: audio 2 In

Costa Rica and Panama, a series of rather sharp downslurred whistles preceded

by a short introductory note, whit..eeeuw...eeeuw...eeeuw ..., uttered

at a rate of about one whistle per second. In the literature, Song in this

region is described as a long series of higher, sharper notes with a most

peculiar intonation (8) or

(in Mexico) a descending, slowing series of plaintive whistles, usually 5‒8, whi'

peeu peeu peeu peeu peeu ..., or wh' wheeu wheeu ... (65).

· Amazonian

group: In Brazil, a series of long melodious whistles, starting with a loud

flat-pitched introductory note and followed by a series of lower-pitched

disyllabic mellow whistles wheeee-pihuuw-pihuuuw-pihuuw.

Another variant is structurally similar, but disyllabic whistles are more

modulated wheeeee-priririuuw-priririuuw... audio Also

described as a squeaky PEE'u occasionally followed by a lower,

musical PEE'u-brrrr (66).

· Pacific

group: Possibly a homologous vocalizations is

described as a squeaky whi-CHEW in a series in a display (66). No

recordings of Song are available.

“Primary call. audio 3 A

short disyllabic nasal keeeyup, repeated many times at intervals of

ca. 2 seconds. On sonogram, note has a characteristic shape, initially reaching

a flat-pitched top around 3 kHz, after which frequency drops sharply with a

hiccup around 2 kHz, for a total duration of about 0.20‒0.25 second. Also

described as a low-pitched sur-líp, sometimes [repeated] over and

over (67); a

loud, mellow, hollow-sounding whistle, usually two-syllabled: keeeyup or

keee-yew (8); a

squeaky to hollow, plaintive whee-uk or see-yuk (65);

and as a loud, plaintive squeak: PEE'yuk (42).”

Three

recordings of the primary call are presented here, one from mexicanus,

one from castelnaui, one from coronatus: https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/royfly1/cur/sounds#vocal. These indeed sound very different from swainsoni,

and sound very similar to each other. No

primary call of occidentalis was presented.

Discussion

This

complex has been on everyone’s radar “forever” in terms of species limits,

especially because classifications in the early 1900s treated them as four

species, and Meyer de Schauensee provided no rationale for the lump. One could argue on that basis alone that a

return to the taxonomy of Ridgway-Cory-Hellmayr-Pinto is warranted, and thus place

burden-of-proof on treatment as a single species.

Based

on qualitative perusal of sonograms of what is called the primary call, one

could easily justify treating swainsoni as a separate species, as done

by Birds of the World. Based on that

same qualitative perusal of N=1 primary calls of mexicanus, coronatus,

and castelnaui, the primary calls sound similar to me, and their

sonograms have that distinctive appearance noted by Kirwan et al. Calls of occidentalis and fraterculus

were not presented, but perusal of xeno-canto suggests that occidentalis

(N=1; https://xeno-canto.org/264700) and fraterculus (N=1; https://xeno-canto.org/664102)

are also qualitatively similar. However,

none of this is a substitute for a quantitative analysis, so that concerns me.

It

is not the job of SACC members to do original quantitative analyses, and this

is what would be ideal for a decision on species limits in Onychorhynchus. The qualitative difference between swainsoni

and the others could be considered sufficient, in my opinion, for placing

burden-of-proof on a single species treatment.

This is also consistent with the genetic data of Harvey et al. (2020)

and Reyes et al. (2023). However, in my opinion, further splits would require

quantitative analyses of the vocalizations.

Studies of contact zones would be the best of all, but occidentalis

is isolated, and I’m not sure if contact zones exist between mexicanus

and fraterculus, fraterculus and coronatus, fraterculus

and castelnaui, or coronatus and castelnaui.

For

voting purposes let’s break this down as follows, with YES/NO votes on the

following

A. Retain traditionally

defined broad O. coronatus. If

YES, then B, C, and D are automatically NO.

B. Recognize two

species (as in HBW and Birds of the World): O. swainsoni and O.

coronatus, which would include all other taxa.

C. Recognize four

species: O. mexicanus, O. occidentalis, O. swainsoni, and O.

coronatus (return to the classification of Cory & Hellmayr and others,

following del Hoyo and Collar 2016):

D. Recognize six

species (O. mexicanus, O. occidentalis, O. fraterculus, O. castelnaui, O. coronatus, and O. swainsoni) for each of the lineages

elucidated by Reyes et al. (2023).

Pending

input from those more knowledgeable than I, my recommendations are as follows:

A. No – the original lump was never justified; B- Yes – based on published

sonograms of primary call note and a genetic distance more consistent with

species rank in related lineages; C. No – this would require additional,

qualitative research on vocalizations in my opinion; D. No – likewise, and I

oppose using mtDNA lineages for taxonomy, particularly because of the

well-known potential problem of gene trees conflicting with species trees; this

point was implicit in Reyes et al.

Literature

Cited:

KIRWAN, G. M., R. SAMPLE, B. SHACKELFORD, R. KANNAN,

AND P. F. D. BOESMAN. 2024a. Atlantic Royal Flycatcher (Onychorhynchus

swainsoni), version 1.1. In Birds of the World (T. S. Schulenberg and B. K.

Keeney, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.royfly5.01.1

KIRWAN, G. M., R. SAMPLE, B. SHACKELFORD, R. KANNAN,

AND P. F. D. BOESMAN. 2024b. Atlantic Royal Flycatcher (Onychorhynchus

swainsoni), version 1.1. In Birds of the World (T. S. Schulenberg and B. K.

Keeney, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.royfly5.01.1

REYES, P., J. M. BATES, L. N. NAKA, M. J. MILLER, I.

CABALLERO, C. GONZALEZ-QUEVEDO, J. L. PARRA, H. F. RIVERA-GUTIERREZ, E.

BONACCORSO, AND J. G. TELLO. 2023. Phylogenetic relationships and biogeography

of the ancient genus Onychorhynchus (Aves: Onychorhynchidae) suggest

cryptic Amazonian diversity. J. Avian Biology 2023: e03159.

WHITTINGHAM, M. J., AND R. S. R. WILLIAMS. 2000. Notes on morphological differences

exhibited by Royal Flycatcher Onychorhynchus coronatus taxa. Cotinga 13: 14-16.

Note

on English names:

BOW uses “Atlantic Royal Flycatcher” for swainsoni and “Tropical Royal

Flycatcher” for everything else. If

Option B passes, then I think we can save ourselves plenty of work and simply

adopt the current BOW names Tropical Royal-Flycatcher and Atlantic

Royal-Flycatcher. If you object and

would like a separate proposal, and are also willing to write that proposal,

speak out. “Tropical” may only be a temporary

name pending more data on future splits.

There will be the usual howls concerning use of names of oceans as names

of terrestrial species, but I think it is widely understood what the

implication of such names are for land birds.

If Option C or D passes, then we will have to do a separate SACC

proposal on English names depending on which taxonomy we adopt. See the illustration above for names used by

BLI for a 4-way split.

Van Remsen, May 2025

Voting Chart: https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart1044+.htm

Comments

from Robbins:

“Van has done an excellent job of distilling the issues with species limits

within coronatus. I agree with

his concluding assessment that more complete genetic sampling (it is

unfortunate that the Harvey et al. UCE data lacked two of the taxa) is needed,

especially from western Amazonia. For

reasons that fieldworkers have known for a long time and was reiterated by Van,

relevant vocal data with sufficient sample sizes may be a long time in

coming. Although there are certainly

more than two species involved, to be conservative at

this point, I follow Van’s recommendations:

“A. NO

B. YES

C. NO

D. NO”

Comments

by Lane:

“YES to B and NO to the other options until a better case is built for

additional splits. I have uploaded my recordings of occidentalis with

the “whi-chew” vocalization (ML637382910... cut off,

unfortunately), suggesting it to be similar to other members of the overall “tropical”

group. I can’t argue that the evidence to split this group up more is

convincing at this time, and thus vote for a 2-species taxonomy largely based

on vocal differences.”

Comments from Areta: “First of all, Reyes et al. (2023) indicated the need of further

sampling and the integration of more lines of evidence in order to sort the

taxonomy of O. coronatus. Thus, any

taxonomic decision taken at this point will not be the most informed one.

“Secondly, I see the phylogenetic tree

of Harvey et al. (2020) as being consistent with that in Reyes et al. (2023),

except that it lacks samples from some key taxa.

“Third, my vote for AviList/WGAC on this

issue before the publication of Reyes et al. (2023) was ‘Initially, assuming the topology and divergences shown in Harvey et al

2020 are representative of this complex, I was leaning towards a 3-way split

(Atlantic Forest, "Amazon", and Central America/Pacific South

America). But after listening to the relatively good sampling of calls across

the range, I agree with the 2-way split:

Atlantic Forest vs rest of the World. I hope someone undertakes a deeper

analysis on Onychorhynchus!"

A. Retain traditionally defined broad O. coronatus. NO

B. Recognize two species (as in HBW and Birds of the World): O.

swainsoni and O. coronatus, which would include all other taxa.

Maybe (see below)

C. Recognize four species: O. mexicanus, O. occidentalis, O.

swainsoni, and O. coronatus (return to the classification of Cory

& Hellmayr and others, following del Hoyo and Collar 2016). NO, this is

untenable in light of the phylogenetic results: how can we split occidentalis (with fraterculus) from mexicanus

without also splitting castelnaui

from coronatus?

D. Recognize six species (O. mexicanus, O. occidentalis, O. fraterculus, O. castelnaui, O. coronatus, and O. swainsoni) for each of the lineages elucidated

by Reyes et al. (2023). NO, this seems to be over-splitting the mexicanus group, which has shallow

divergences. The biogeographic pattern linking birds from NW South America and

the Pacific of Ecuador and Peru to birds from Central America-Mexico is not

unusual. Sometimes the taxa have speciated, sometimes they have not. In this

case, I don´t think the level of divergence justifies splitting them as

biological (or recognition) species.

“To me the dilemma is whether we should

recognize 2 species (swainsoni and a

polytypic coronatus; Van´s Option B)

or 4 species (swainsoni, castelnaui, coronatus, and a polytypic mexicanus;

my new Option E). Both alternatives are compatible with phylogenetic data, and

the genetic divergence between the W Amazonian castelnaui and the mexicanus

group is nearly as deep as that between these two groups and coronatus. I examined the calls

unsystematically again, and the vocalizations seem very similar. It could be

that coronatus might have a slightly

higher pitched and perhaps shorter call than castelnaui, but the vocalizations are overall quite similar, and a

proper study is needed to increase our understanding of vocal variation in the

phylogroups uncovered by Reyes et al. 2023. Given the (apparent!) vocal

similarities and the not-so-deep (but also not-so-shallow) genetic differences

between castelnaui-coronatus-mexicanus,

I vote for option B for now. If new information appears, or someone with a

deeper understanding of vocalizations of the group uncovers diagnostic

differences in calls of these groups, I would be delighted to support my option

E, but at present I think that the information is not there to show that this

is the best option.”

Comments

from Naka:

“As you have guessed, there is a reason why we decided not to propose a

complete taxonomic rearrangement of this species in the Reyes et al. article,

mostly due to lack of i) nuclear data and ii) proper morphological and vocal

assessment in the clade. Although I agree with the major finding of the

article, that the six taxa involved likely represent six independent lineages,

I would not encourage, nor vote for a 6-species split at this stage. As we all

know, mDNA is great in reaching reciprocal monophyly,

yet it represents a bad proxy for gene flow. Therefore, we lack that key piece

of evidence to declare these taxa as fully independent lineages beyond a

reasonable doubt (meaning, these can fall apart in the next genomic study).

“I

personally like the idea of having three biogeographically-sound main lineages,

including i) a similar sounding Middle American/trans-Andean taxon (including

mexicanus, occidentalis, and fraterculus, although I wish the dry

forest occidentalis would sound any different!); ii) a rather distinct

Atlantic Forest taxon (swainsoni); and an Amazonian lineage (O.

coronatus + O. castelnaui). However, this arrangement contrasts with

the mtDNA results, which show that the two Amazonian forms are not sister taxa,

as first found by our study back in 2018 (Naka and Brumfield, 2018). Therefore,

the options here (if we are to follow the mtDNA tree), are to have 2, 4 or 6

lineages. At this stage, given the lack of better genetic resolution, and the

poor vocal sampling available, I will vote for option B.

In

short:

“A. NO, to Retain

traditionally defined broad O. coronatus.

“B. YES, to Recognize

two species (as in HBW and Birds of the World): O. swainsoni and O.

coronatus, which would include all other taxa.”

“C.

NO

“D.

NO”

Comments

from Stiles:

“A. YES; B. NO - the evidence for further splits is weak and inconsistent as it

stands: more data required: C. NO; D. NO.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“A.

NO.

“B.

YES.

“C.

NO

“D.

NO.

“Personally,

the arrangement that makes the most sense to me intuitively, is the 4-way split

(i.e. Return to the classification of Cory & Hellmayr), but I don’t think

this option is rigorously defensible on current knowledge. I feel pretty confident from personal

experience that swainsoni is worthy of being elevated to species rank,

based upon noted vocal differences, genetic data, plumage, ecological

differences and distribution and how those fit established biogeographic

patterns. As an aside, I don’t think

that the illustrations included in the Proposal adequately convey just how

different occidentalis and swainsoni are in overall color from

the much duller Amazonian taxa that occupy the intervening areas – both of

those taxa, one occupying dry forest and the other Atlantic Forest are really

richly ochraceous and very different from other taxa in the complex. Regardless, I think the best course of action

for now, at least in terms of what is well supported by existing data, is the

conservative two-way split of swainsoni versus everything else. In that case, Van’s suggestion that we adopt

the existing BOW names of Atlantic Royal-Flycatcher for swainsoni, and

Tropical Royal-Flycatcher for everything else makes the most sense, with the

latter name being easily changed to adapt to any further splits.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“

“A. NO. As several SACC members

have already acknowledged, there is preliminary evidence suggesting that

maintaining the traditionally defined O. coronatus may overlook the complexity of the group.

“Still,

obtaining complete vocal data for all populations could prove very difficult.

Based on our experience with the western Ecuadorian population (O. coronatus

occidentalis), gathering vocalizations from this taxon will be particularly

challenging due to its rarity, highly localized distribution, and potential

seasonal movements throughout the year.

“B. YES. For the time being,

based on limited nuclear (UCE) and mitochondrial (ND2) data (both topology and

distances), and qualitative vocal differences, it seems safe to call O. swainsoni a separate species from O. coronatus.

“C. NO. More data are

needed.

“D. NO. More data are

needed.”

Comments

from Glaucia Del-Rio (guest vote):

“A.

NO

“B.YES

“C.

NO

“D.

NO

“I

do not think the available data justify splitting beyond the two-species

treatment. As mentioned before, mitochondrial DNA, while useful for revealing

genealogical structure, is not sufficient to delimit species. For me, the

consistent placement of O. swainsoni as the deepest lineage in both

mtDNA and UCE studies, and its distinctive plumage and vocal differences,

provide sufficient evidence to recognize it a different species from the O.

coronatus complex.”