Proposal (1056) to South American Classification Committee

Treat the musculus

subspecies group as a separate species from Troglodytes aedon

Note

from Remsen: This is a NACC proposal that is here relayed

to SACC but severely pruned from the original NACC proposal to eliminate the

sections on all the extralimital Caribbean taxa (mostly now treated as separate

species by NACC); Brian Sullivan and I were co-authors on the original, but

that was strictly on the extralimital Caribbean taxa, which we predicted

therein were not a monophyletic group, subsequently confirmed by Klicka et al.

(2023). The NACC proposal passed 9-1,

and it also passed WGAC.

Effect

on SACC: This

would change what we currently consider as House Wren (Troglodytes aedon)

to Southern House Wren (T. musculus).

Background:

This

is an update of NACC Proposal 2022-B-10 by Remsen, Jaramillo, and Sullivan,

which proposed to recognize as many as seven species in the Troglodytes

aedon complex in the Caribbean. The proposal failed 5-6 (with 10c and 10g

failing 4-7). However, nearly all NACC members who voted no in 2022

acknowledged that multiple species must be involved in the complex, but that a

comprehensive integrative study is needed before action should be taken. Now, a

near-comprehensive phylogeny based on mtDNA and genomic data has appeared

(Klicka et al. 2023) and provides an opportunity to reevaluate the complex.

However, this now needs to be done from a broader perspective, given the

pattern shown in Klicka et al. (2023). In addition, reevaluation of other

papers provides a more integrative approach for examining species limits of all

but the rarest (or extinct) taxa. Although some of the relationships in the

complex clearly require further population and genetic sampling and analysis,

as indicated in Imfeld et al. (2024), we consider that sufficient data now

exists and is summarized herein to enable several changes to the current

taxonomy.

Committee

members can review the 2022 proposal (https://americanornithology.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/2022-B.pdf) and comments

(https://americanornithology.org/about/committees/nacc/current-prior-proposals/2022-proposals/comments-2022-b/#2022-B-10)

in conjunction with this proposal, as there is much information therein that is

not repeated here, mostly on the extralimital Caribbean taxa.

New

information:

More

taxa are included in the mtDNA phylogeny than in the genomic tree of Klicka et

al. (2023), and, not unexpectedly, the results differ somewhat. We focus here

on the genomic phylogeny and supplement that with data from the mtDNA phylogeny

for taxa missing from the former. Note

that Klicka et al. (2023) refer to all Caribbean samples as “T. a.

martinicensis”, even though the included samples are from Trinidad,

Grenada, St. Vincent, and Dominica, and thus must represent albicans, grenadensis,

musicus, and rufescens, respectively (this is made clear in the

supplementary materials). This may mislead some readers into thinking that one

taxon (martinicensis from Martinique) falls into multiple clades, which

is not the case; in fact, that extinct taxon is not included in the sampling.

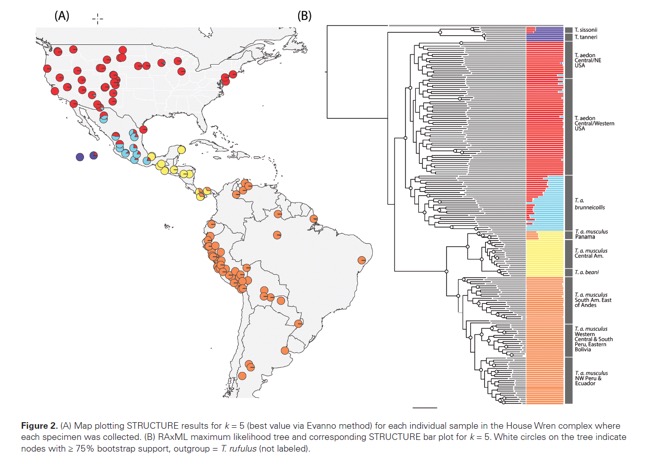

Troglodytes

musculus.—The

most compelling result from the Klicka et al. (2023) phylogeny is that on

genomic data there are two main clades of Troglodytes aedon: the aedon

and musculus clades. The aedon clade (including brunneicollis)

occurs from southern Canada southward through the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, and

in Mexico it is largely a bird of pine-oak woodland in the highlands, whereas

the musculus clade occurs in a variety of habitat types and elevations

from southern Veracruz and northern Oaxaca through the Yucatán Peninsula and

southward through South America. The STRUCTURE results do not show

intergradation between these two groups, although sample size from the relevant

area is small.

(from Klicka et al.

2023)

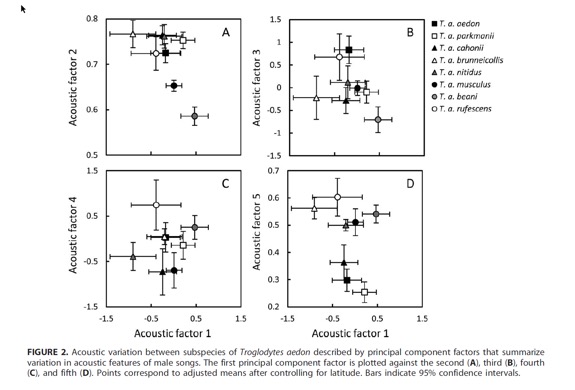

Howell

and Webb (1995) treated the musculus group separately, as “Troglodytes

aedon (in part) or T. musculus”. They considered the songs of these

two groups not reliably distinguishable, but Sosa-López and Mennill (2014)

found some vocal differences between them, as well as between other taxa that

are not presently considered candidates for species level.

(from Sosa-López and

Mennill 2014)

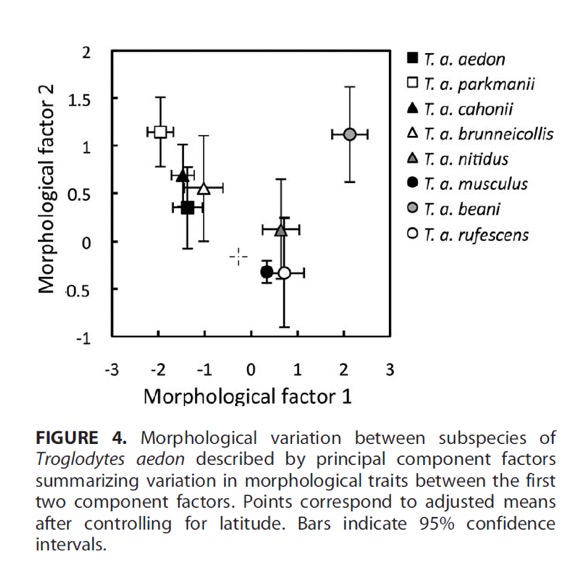

These

authors also demonstrated mensural differences between the aedon and musculus

groups:

’

’

(from Sosa-López and

Mennill 2014)

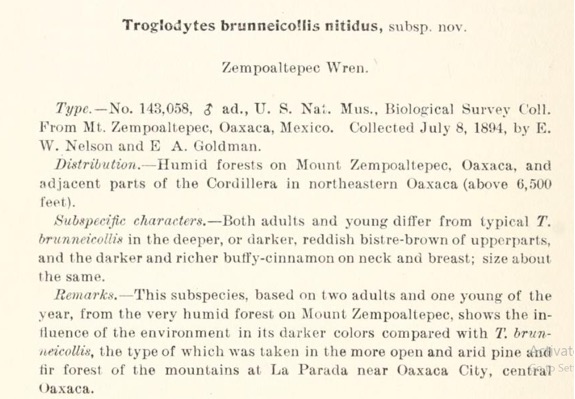

although

the disputed race nitidus (e.g., placed in the brunneicollis

group in Clements but not recognized at all by IOC-WBL) groups here with musculus,

not brunneicollis, etc. This seems unsurprising as nitidus is

from mountains of northern Oaxaca, thus near or at the contact zone between brunneicollis

and intermedius of the musculus group. But Nelson’s (1893)

description of nitidus indicates it is darker and more reddish-brown

than typical brunneicollis, so it could be variable, be more like brunneicollis

in color but more like intermedius in measurements, or perhaps both

forms occur in sympatry in the region. More study obviously needed on that.

(from Nelson 1893)

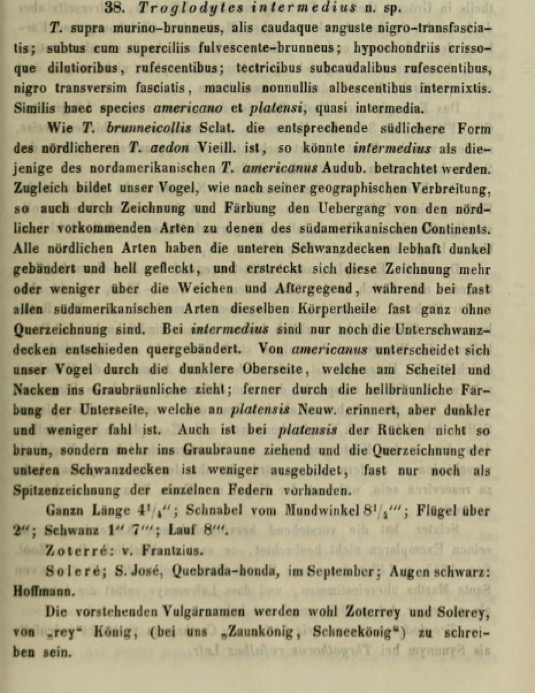

OD

of the geographically adjacent subspecies, intermedius Cabanis, 1861:

Google

translation:

“above murine-brown, wings and tail narrowly

barred with black; below with the eyebrows yellowish-brown; with hypochondria,

more and more diluting, blushing; with rufous subcaudal coverts, banded

transversely with black, interspersed with some whitish spots. This species is

similar to the americano and the platensi,

as if intermediate.”

“Just as brunneicollis is the

corresponding southern form of the more northern aedon [eastern Canada

and US], so intermedius could be viewed as that of the North American americanus

[=parkmanii] [western Canada and US]. At the

same time, our bird forms the transition from the northern species to those of

the South American continent through markings and coloring, as does its

geographical distribution. All northern species have the lower caudate coverts

vividly dark and brightly spotted, and this marking extends more or less over

the wings and anal area, while in almost all South American species the same

parts of the body are almost entirely without transverse markings. In intermedius

only the undertail coverts are clearly cross-banded. Our bird differs from americanus

in its darker upper side, which turns grey-brown on the crown and neck;

furthermore, by the light brownish color of the underside, which is reminiscent

of platensis Neuw., but is darker and less

pale. The back of platensis is also not so brown, but more of a

gray-brown color, and the transverse markings on the lower tail coverts are

less developed, almost only present as tip markings on the individual feathers.”

In

essence, Cabanis was stating that his new form intermedius is similar to

western North American birds, not to the geographically adjacent brunneicollis.

In any case, if there is a zone of intergradation, it seems it must be a narrow

one. And this marked discontinuity in phenotype in near-parapatry has been

known a long time and has now been demonstrated to be real based on the Klicka

et al. (2023) phylogeny, although a larger sample size in this region and more

focused study on this aspect is needed to better understand the interactions

between these two forms.

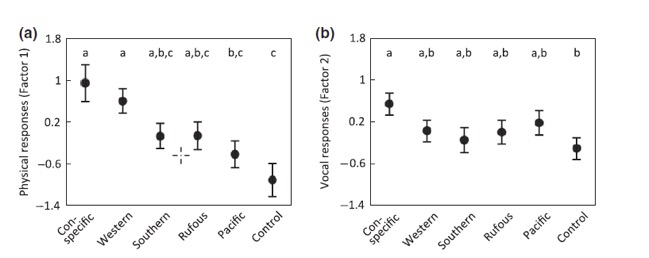

Sosa-López

et al. (2016) analyzed response to playback with respect to mtDNA divergence:

(from Sosa-López et al.

2016)

and

found that brunneicollis (a, b) responded more strongly physically (but

not vocally) to Western than to Southern house wrens, with the response to the

latter at the level of the non-conspecific Rufous-browed and only slightly

higher than to Pacific Wren.

So,

there is a good case to be made for splitting the intermedius group of musculus

from the aedon group including brunneicollis. The most obvious

problem with this is that there is some gene flow in Panama with the South

American musculus group, so simply splitting musculus from the

southern Mexico-Central American intermedius group requires further

study and has nomenclatural implications. And, as for the evidence for

considering the intermedius and musculus groups separate species,

if it has ever been seriously considered it is not evident in the papers

reviewed here, and for now we consider intermedius a group within the musculus

complex.

Troglodytes

brunneicollis.—mtDNA

phylogenies including that in Klicka et al. (2023) showed brunneicollis

as paraphyletic with several outgroups, thus strongly suggesting species status

for brunneicollis. However, this result has not held up in the genomic

analysis of Klicka et al. (2023), and furthermore broad introgression with aedon

in the southwestern USA has been shown to occur (as was already apparent from

plumage).

Troglodytes

parkmanii.—As with brunneicollis, mtDNA

phylogenies, including that in Klicka et al. (2023), showed parkmanii

as paraphyletic, but this is again not the case for the genomic phylogeny, in

which it groups with aedon. They have been shown to be vocally different

and to have some reduced response, but the differences are not at the scale of

the other taxa studied (for which see below).

Recommendations: (The original proposal included separate

recommendations, both NO, on whether to split brunneicollis from aedon,

and whether to split parkmanii from aedon;

both were voted down, and given that these extralimital taxa are in the NACC

area only, that part of the proposal is excluded from the SACC version).

We

strongly recommend a YES vote to splitting musculus (including the intermedia

group) from the aedon group (including the brunneicollis group).

Should the intermedia group be split later from the musculus

group, the species-level nomenclature would have to change for the Central

American group to intermedia, but we think the evidence for the split

between the aedon and musculus groups is overwhelming.

English

names:

NACC went with Northern House Wren and Southern House Wren. Unless someone objects and would like to do a

separate proposal on English names, I think we should follow NACC. Note the absence of a hyphen because the two

are not necessarily sister taxa with respect to Caribbean taxa or T. cobbi.

Literature

Cited (in

the original, lengthier proposal):

Cyr, M.È., K. Wetten, M.H. Warrington, and N. Koper. 2020. Variation in

song structure of house wrens living in urban and rural areas in a Caribbean

small island developing state, Bioacoustics https://doi.org/10.1080/09524622.2020.1835538

del Hoyo, J., and N.J.

Collar. 2016. HBW and BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the

Birds of the World. Volume 2: Passerines. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Imfeld, T.S., F.K.

Barker, H. Vázquez-Miranda, J.A. Chaves, P. Escalante, G.M. Spellman, and J.

Klicka. 2024. Diversification and dispersal in the Americas revealed by new

phylogenies of the wrens and allies (Passeriformes: Certhioidea). Ornithology

(early view).

Kirwan, G.M., A.

Levesque, M. Oberle, and C.J. Sharpe. 2019 Birds of the West Indies. Lynx and

BirdLife International Field Guides. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Klicka, J., K. Epperly,

B.T. Smith, G.M. Spellman, J.A. Chaves, P. Escalante, C.C. Witt, R.

Canales-del-Castillo, and R.M. Zink. 2023. Lineage diversity in a widely

distributed New World passerine bird, the House Wren. Ornithology 140:1-13.

Sosa-López, J.R., and

D.J. Mennill. 2014. Continent-wide patterns of divergence in acoustic and

morphological traits in the House Wren species complex. The Auk: Ornithological

Advances 131: 41-54.

Sosa-López, J.R., J.E.

Martínez Gómez, and D.J. Mennill. 2016. Divergence in mating signals correlates

with genetic distance and behavioural responses to

playback. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 29:306-318.

Wetten, K.N. 2021.

Morphological divergence in the House Wren (Troglodytes aedon) species complex:

A study of island populations with a focus on the Grenada House Wren (T. a.

grenadensis). Master’s Thesis, University of Manitoba.

Pamela C. Rasmussen,

May 2025

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Vote tracking chart:

https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart1044+.htm

Comments

from Claramunt:

“YES. Both mitochondrial and nuclear-genomic data indicate the existence of two

independent lineages that, despite geographic proximity, have not been

exchanging genes. Response to each other’s songs is moderate, but there must be

other mechanisms of isolation in order to prevent gene flow, which is not

happening.”

Comments from Areta: “YES. This is a solid result supported by differences in plumage,

habitat, vocalizations, and genetics.”

Comments

from Lane:

“NO. Honestly, I am having a bit of a hard time navigating the proposal and

feeling like the conclusions are as solid as they are made out to be. My main

issue is that the crux of the problem is in the Gulf slope of Mexico north/west

of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, where the brunneicollis group (here a

member of the northern aedon group) and the intermedius group

(here a member of the musculus group) come into contact or are

parapatric. To me, this is the only important area, and it is hardly addressed

with more than a little lip service. I am assuming that the Klicka et al.

(2023) paper is the primary source for the phylogenetics used in the proposal,

but in that paper, there are not many samples made from the crucial area of the

lowlands of Oaxaca and the nearby highlands. There is mention made of the named

taxon nitidus, but then it is effectively ignored even though it was

described, then synonymized by Binford (1989) with brunneicollis. The

proposal mentions that nitidus is a musculus population, but I

don't understand the basis for that statement! Klicka et al. don’t seem to have

sampled that population, and phenotypically it appears to be very similar to brunneicollis

(as per Binford’s comment), so how was it determined to be a member of the musculus

group? In the supporting files of Klicka et al, I see 3 Veracruz samples

(presumed intermedius) and 3 Oaxaca samples (presumed brunneicollis).

In the mtDNA tree built there (and reflected in Figure 1 of the main paper), it

is noteworthy that the bulk of the brunneicollis clade is not only not

sister or embedded within the aedon clade, but outside the entire T.

solstitialis clade as well! However, the six samples from the

Veracruz/Oaxaca area are not found to fall out together, nor do they seem to in

the SNP tree that is reflected in Figure 2 of the paper (and reproduced in the

proposal). But this small sample does not quench my interest in what exactly is

going on at this crucial place! I would really like to see a more in-depth

study of the lowland Gulf slope populations and the highland brunneicollis

here to determine if they truly are not interbreeding. Do they even have the

opportunity to interact and remain elevationally/habitatly

(did I just invent a word?) parapatric? In my limited experience in the area,

they seem to be parapatric. But overall, I am remarkably underwhelmed by any

phenotypic and vocal differences between the musculus group and aedon/brunneicollis

group(s). In fact, to me brunneicollis is by far the most distinctive in

voice and habitat choice of the whole complex! So, to have spent so little

effort in trying to investigate this limited area of potential interaction in

eastern Mexico makes me nervous in drawing such large conclusions about the

complex. Until I feel like that is done, I just can’t bring myself to agree

with this split. NO.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“YES to splitting of musculus from aedon; I note that Dan´s

worries about nomenclature are all within the aedon clade and don't

alter the split of musculus.”

Comments

from Remsen:

“YES, but with extreme reluctance. If

NACC and AviList had not already endorsed the split and if the 2-species

treatment had been novel instead of a widespread treatment in many earlier

classifications, I would vote NO. I

share Dan’s concerns – this all makes me uneasy because despite all of the new

data on genetics and voice, no one has critically studied the contact zone in

Mexico. Contact zones provide direct evidence

on how populations interact with each other in terms of gene flow, and they remove

the need to make inferences and indirect yardstick comparisons. My YES vote is based on the assumption that,

as noted in the proposal, that if the two populations intergrade in Mexico,

then this would have been known a long time ago from studies of specimens, so

even though the genetic sampling in the critical area is remarkably weak in the

new studies (as noted in Pam’s proposal), all signs, phenotypic or genotypic

(the deep genetic split between the clades), point to an absence of a hybrid

swarm. Binford, for example, would very

likely have picked up on this in his studies of the avifauna in Oaxaca. So, if forced to justify my vote based on

more than momentum and the palliative of returning to a previous taxonomy, this

absence of any sign of a hybrid swarm would be my main argument. Regardless, what’s going on in that contact

zone would be of general interest and, as far as I can tell, would be an easy

field study.

“As far as the evidence discussed in

the papers as outlined in the proposal, much of it, albeit interesting and

important, is not particularly relevant to species limits. The differences in measurements and plumage are

not really relevant to species limits unless used as a proxy for gene flow in

the vicinity of the contact zone.

Similarly, habitat differences in this complex are about as

irrelevant as they can be. Just within

the musculus group in Bolivia, one can find House Wrens singing in

frigid dusty towns in the Titicaca Basin to sweltering jungle towns in the

Beni, thus spanning a remarkable climatological range. The North American aedon group spans

an ecological gradient almost as steep, from aspen groves at 10,000 feet in

Colorado to near sea level in hot humid coastal North Carolina. When we invoke “integrative” taxonomy in our

decisions, there is a tendency to ignore the point that many of the points that

are integrated are irrelevant to species limits unless they apply to contact

zone regions and thus acts as a proxy for gene flow. I think we take too much comfort in listing a

bunch of phenotypic differences that are not directly relevant to species

limits unless from regions in which there are contact zones.

“As for the playback experiments, if we

take them as evidence for splitting musculus from aedon, then we

should also take them as evidence for splitting brunneicollis from aedon,

as advocated by Sosa-López and Mennill (although that is out of SACC’s

geographical purview), despite the Structure plot that shows some evidence of

gene flow. In general, playback

experiments in wrens seem tricky, as evidenced by the Sosa-López results. Anecdotally, for example, here in Louisiana

in winter, House, Sedge, Marsh, and Carolina will regularly respond moderately

aggressively to playback of each other’s songs.

“So, after all that preaching, I

conclude no real harm done in returning to species limits that were in place in

many earlier classifications despite absence on nail-in-coffin study of contact

zones.”

Comments

from Robbins:

“I too feel on the fence on this one given known hybridization between birds in

central Panama and the lack of adequate sampling of the two genetically

distinct clades at the zone of contact in southeastern Mexico. I don't have

access to specimen material to see if birds involved in hybridization in

central Panama are less or more distinct than birds in contact in SE

Mexico. Having said that, we know plumage in at least North American

wrens has little to do with species limits, a good example is Eastern and

Western Marsh Wrens — virtually identical in plumage but have distinct songs

and are quite different genetically.

“Ascertaining

relevant differences in vocalizations is difficult in this entire

complex. Within migratory US populations, broadly speaking, western birds

sound distinct from eastern birds, so are relatively minor differences in

vocalizations in other areas meaningful? I suspect one would find song

variation among all groups that are not migratory. I consider playback

experiments to be of little value with this group, as Van correctly points out,

one can get intergeneric response in at least North American wrens.

“So,

in my opinion, we are basing this decision on genetics without enough

information on the contact zone to help guide what is the best course of

action. If NACC hadn't voted for the split, I would vote NO and would wait

until we have more information from the contact zone in SE Mexico. But, given

their decision, with reservations, I'll vote YES for recognition of the split.”

Comments

from Bonaccorso:

“YES. The deep split between these two taxa seems to be telling a lot

about the historical separation of these two lineages. Even if there is not

enough sampling from a potential contact zone, the lack of Central America

genotypes in the North American Lineage and vice-versa seems to indicate that

there is no current gene flow. Also, even if there was hybridization at the

contact zone, if genetic distance is any indication of potential reproductive

incompatibilities, it is likely that such hybridization is very restricted and

constantly limited by natural selection.”

Comments

from Naka:

“YES. I have been using musculus for the South American populations for a very

long time now, and I am happy to maintain that treatment in face of the strong

molecular evidence showing that they represent independent lineages with no

signs of admixture (or historical gene flow) between any of the musculus

and aedon populations. Also, I consider that most of the discussions

about gene flow between brunneicollis and nominate aedon, do not

affect our treatment for a South American musculus, which is strongly

supported by molecular data. I agree that vocal and phenotypic data may not be

that important in a species with such high climatic and habitat plasticity.

Now, If you ask me what I think would happen if we throw a population of musculus

in Mexico city or Texas, I would remain silent. But I

do believe that this has not happened for a reason and suspect the advance of aedon

into the south or musculus further north was likely prevented by

competitive exclusion.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“YES. The evidence for two main clades on independent evolutionary trajectories

appears strong, even if the contact zone in Mexico hasn’t been well sampled

from a genetic standpoint. As Van points

out, if there was a broad hybrid zone in southern Mexico, it almost surely

would have been already known from examination of specimens. I’ve never been overly impressed with vocal

differences in this complex (other than those between insular Caribbean taxa

versus mainland taxa, which are VERY different), but that having been said, I

would agree with Mark and Van that voice and response to playback are probably

not nearly as meaningful with wrens in general as they are in other

groups. Similarly, I think habitat is

incredibly plastic within this group, and really shouldn’t factor into the

equation. I share Dan’s queasiness with all

of the questions concerning the true affinities of intermedius and with

the lack of data from contact zones in southern Mexico in general, but I think,

in the absence of strong evidence of intergradation/hybridization, the genomic

and mtDNA analyses referenced in the Proposal should be considered sufficient

to recognize the proposed split of the musculus-group from the aedon-group.”