Proposal (1057) to South

American Classification Committee

Revise

species limits in Automolus ochrolaemus.

A. Treat extralimital Central American exsertus as a separate

species; B. Treat extralimital Middle American cervinigularis as a

separate species (from exsertus and ochrolaemus)

Note

from Remsen:

The two parts of this proposal are separate proposals relayed from NACC, which

treated exsertus as a separate species in 2018 (Chesser et al. 59th

Supplement 2018; proposal 2018-A-2) and cervinigularis as a separate

species in 2024 (Chesser et al. 65th Supplement 2024; proposal 2024-c-22;

passed 8-2). We have to process these

because they affect what SACC considers to be A. ochrolaemus and also

because these extralimital splits potentially affect our English names.

Also,

the sequence of the proposals and the names can be confusing because they were

separate proposals in NACC. The first

one A deals with splitting Pacific slope exsertus from everything else,

namely broadly defined ochrolaemus, and then B deals with splitting the

rest of the Middle American populations (as cervinigularis) from the

basically South American ochrolaemus.

Effect

on SACC:

No effect other than to change what we would assign to the range of A.

ochrolaemus

Our

current SACC note reads:

85c. Chesser at al. (2018)

treated the Central American exsertus group as a separate species

following the results of Freeman and Montgomery (2017). Dyer and Howell (2023) treated exsertus

group and the Middle American cervinigularis group as separate species

from A. ochrolaemus. Chesser et

al. (2024) treated Middle American cervinigularis as a separate species

from A. ochrolaemus based on comparative genetic distances (Smith et al.

2014). SACC

proposal needed.

Part

A. Treat Automolus ochrolaemus exsertus as a separate species from Buff-throated

Foliage-gleaner A. ochrolaemus

Background: Automolus ochrolaemus, the Buff-throated

Foliage-gleaner, is found in humid lowland forests across a large swath of

Central and South America. There is substantial plumage, vocal and genetic

variation within its broad distribution (see Smith et al. 2014 for

phylogeographic structure, and Remsen 2017 for descriptions of plumage and

vocal variation). This proposal concerns two of the populations found within

Central America: exsertus, which

occurs on the Pacific slope of Costa Rica (and adjacent western Panama), and hypophaeus, which is found along the

Caribbean slope of Central America. These two populations are geographically

isolated and ~ 6% different in mtDNA (cyt b), suggesting they last shared a

common ancestor around 3 million years ago. They differ in voice and are roughly

similar in plumage (Remsen 2017).

New information: Freeman and Montgomery (2017) conducted playback

experiments on 15 territories of exsertus

and 14 territories of hypophaeus.

Each playback experiment measured whether populations discriminated against

song from the other population; thus, these experiments simulated secondary

contact between these two geographically isolated populations. Briefly, each

experiment measured the behavioral response of a territorial bird to two

treatments: 1) song from the local population (sympatric treatment) and 2) song

from the allopatric population (allopatric treatment). All territorial birds

responded to sympatric song by approaching the speaker (typically to within 5

m).

We defined song discrimination as

instances in which the territory owner(s) ignored allopatric song, defined as a

failure to approach within 15 m of the speaker in response to the allopatric

treatment. We calculated song discrimination for each taxon pair as the

percentage of territories that failed to approach the speaker in response to

allopatric song. For example, a song discrimination score of 0.8 indicates that

80% of territorial birds (e.g. 8 out of 10) ignored allopatric song while

simultaneously actively defending a territory. We assume that song

discrimination is a proxy for premating reproductive isolation; that is, our

experiments provide insight into whether these populations would recognize each

other as conspecific and interbreed (or not) were they to come into contact

with one another. It is unknown what degree of song discrimination is “enough”

that song constitutes a strong enough premating barrier to reproduction that

allopatric populations merit classification as distinct biological species. To

provide a yardstick, we considered nine allopatric Neotropical taxon pairs that

were recently split (or have pending proposals to the South American

Classification Committee) in part based on differences in vocalizations. We

found the average song discrimination in these nine taxon pairs to be ~ 0.6

(60% of territorial birds ignored allopatric song) and suggest that species

limits deserve to be reconsidered when taxon pairs currently classified as

subspecies have song discrimination scores above ~ 0.6.

We found that 13 out of 15 territorial

birds from the Pacific slope of Costa Rica (exsertus)

discriminated against song playback of Caribbean hypophaeus (discrimination = fail to approach within 15 m of the

speaker). Results were similar in the

opposite direction: 12 out of 14 territorial birds from the Caribbean slope of

Costa Rica (hypophaeus) discriminated

against song playback of Pacific exsertus

(discrimination = fail to approach within 15 m of the speaker).

Recommendation:

Populations of Buff-throated

Foliage-gleaners from the Pacific and Caribbean slopes of Costa Rica respond

strongly to local song but essentially ignore song from their relatives across

the mountains. This suggests that vocal differences constitute a strong

premating barrier to reproduction between these taxa and is consistent with the

genetic data that indicates that, despite their close geographic proximity,

these populations last shared a common ancestor ~ 3 million years ago. I

therefore recommend treating exsertus and

hypophaeus as distinct biological

species. In practice, this means that I recommend treating exsertus as a distinct biological species from the entire rest of

the Buff-throated Foliage-gleaner complex. There may be additional biological

species lurking within this complex. For example, we documented strong song

discrimination between hypophaeus and

pallidigularis (found in eastern

Panama and northwestern South America; these two taxa presumably interact in a

contact zone in central Panama and may prove to be distinct biological species.

As for an English name for exsertus,

Ridgway (1911) and Cory and Hellmayr (1927) called it "Chiriqui

Automolus", which would translate to "Chiriqui Foliage-gleaner",

which would seem to be a reasonable name.

Literature

Cited:

Freeman,

B. G., & Montgomery, G. A. 2017. Using song playback experiments to measure

species recognition between geographically isolated populations: A comparison

with acoustic trait analyses. The Auk 134(4), 857-870.

Remsen,

J.V., Jr (2017). Buff-throated Foliage-gleaner (Automolus ochrolaemus).

In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E.

(eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions,

Barcelona. (retrieved from http://www.hbw.com/node/56571 on 20 October

2017).

Smith,

B.T., McCormack, J.E., Cuervo, A.M., Hickerson, M.J., Aleixo, A., Cadena, C.D.,

Perez-Eman, J., Burney, C.W., Xie, X., Harvey, M.G. and Faircloth, B.C., 2014.

The drivers of tropical speciation. Nature 515.

406-406.

Benjamin

Freeman, May 2025

Part

B. Treat Automolus cervinigularis as a separate

species from Buff-throated Foliage-gleaner

A. ochrolaemus

Description of the

problem: Automolus ochrolaemus (Tschudi, 1844)

is a wide-ranging polytypic species of the lowland Neotropics, found in lowland

rainforest nearly throughout the Neotropics from southern Mexico through the

Amazon Basin. Until 2018, this was generally considered a single polytypic

species with seven subspecies. From north to south, these taxa are: cervinigularis (Sclater, 1857) of Mexico

to Guatemala; hypophaeus Ridgway,

1909 of Nicaragua to northwestern Panama on the Caribbean slope; exsertus Bangs, 1901 of the Pacific

slope of Costa Rica and far southwestern Panama; pallidigularis Lawrence, 1862 of eastern Panama south through the

Choco to northwestern Ecuador; turdinus

(Pelzeln, 1859) of the western Amazon Basin and Guiana Shield; ochrolaemus (Tschudi, 1844) of the

southwestern Amazon Basin; and auricularis Zimmer, 1935 of the southeastern

Amazon Basin (Birds of the World, 2023). Another subspecies, amusos, is sometimes recognized from

Honduras and Nicaragua, or considered a synonym of cervinigularis or hypophaeus.

Ridgway (1911) considered the complex to

comprise three species: A. cervinigularis

(including hypophaeus), A. pallidigularis (including exsertus), and although not covered in

his volumes, implicitly considered A.

ochrolaemus for all the extralimital taxa.

NACC proposal 2018-A-2 elevated exsertus to species rank based on

allopatry from hypophaeus,

mitochondrial divergence, and song discrimination in playback trials between exsertus and hypophaeus, and NACC adopted the English name Chiriqui

Foliage-gleaner. NACC adopted this split 8-2, with some committee member

comments mentioning that the rest of the taxa found west of the Andes might

eventually be split from the Amazonian taxa, pending further research. WGAC, in

addressing discrepancies among global lists, also chose to adopt the split of A. exsertus, but went one step further

and split the other two Middle American taxa as a species (A. cervinigularis, with hypophaeus)

separate from the South American taxa. They opted, however, to retain pallidigularis of eastern Panama and the

Choco with A. ochrolaemus of the

Amazon Basin and Guiana Shield.

New information:

1. Genetics:

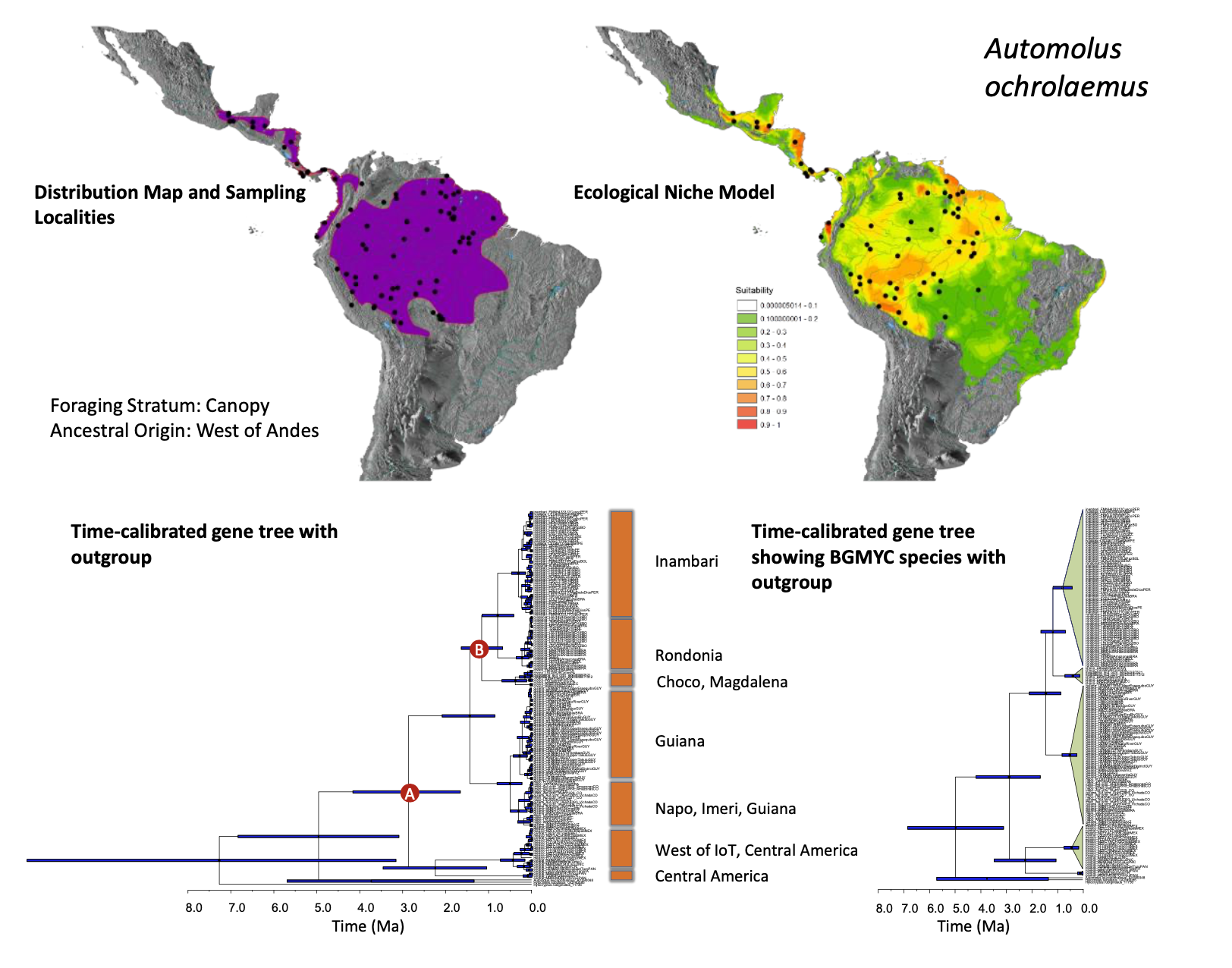

Smith et al. (2014) sampled all taxa in this

group using the mitochondrial gene cytochrome b and estimated a gene tree that

was fairly well resolved. Below is the supplemental figure for the genus from

Smith et al. (2014) showing the sampling map, ecological niche model, and the

gene tree. On the left is the time-calibrated gene tree, and on the right is

the same tree with species as circumscribed by the species delimitation method

bGMYC.

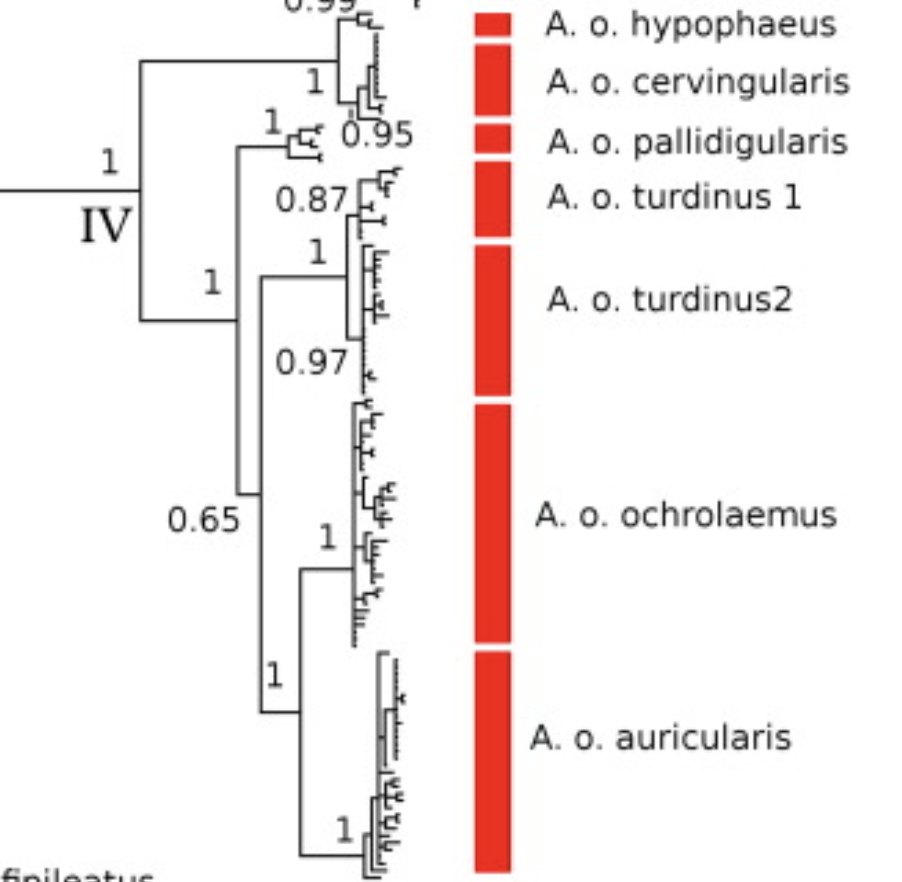

Broadly, Smith et al. (2014) found that exsertus and cervinigularis/hypophaeus were sister groups, which in turn were

sister to the remainder of the ochrolaemus

complex. The Choco taxon pallidigularis was

embedded within the rest of the South American taxa from east of the Andes. To

better illustrate these relationships, I have included an enlarged version of

the bGMYC tree above, with the corresponding taxa labeled to the right of each

cluster. Note that that outgroup has been removed here to better highlight the

few samples of exsertus at the bottom

of the tree. The time scale is in millions of years.

Shultz et al. (2017) sampled two mitochondrial

genes (ND2 and cytochrome b) for most taxa in the group, except exsertus, and recovered a similar

topology to Smith et al. (2014). However, they recovered pallidigularis as sister to the remaining South American taxa

rather than embedded within them. Shultz et al. (2017) also sequenced three

nuclear genes for these samples, but they showed no differentiation across the

group, as is often the case. They are not shown here.

Harvey et al. (2020) sampled two individuals in

the complex: one hypophaeus from

Costa Rica and one turdinus from

Peru. These samples were sisters, with a divergence time of about 2 Ma, which

is consistent with the mitochondrial data, but doesn’t provide much information

for taxonomy.

Claramunt et al. (2013) sequenced three

mitochondrial and three nuclear genes and recovered a topology consistent with

the other studies included here, with pallidigularis

clustering with the Amazonian taxa, and hypophaeus

sister to the rest (exsertus, cervinigularis, and auricularis not sampled). A portion of the tree from Claramunt et

al. (2013) is shown below.

2. Voice:

Although nothing is published on vocalizations

that I can find, there is considerable vocal variation in the group, and this

is partly the basis for elevating exsertus

to species rank. In listening to vocalizations, there are essentially two vocal

groups in the complex: one with a slower series of nasal descending notes

comprised of ochrolaemus, auricularis, turdinus, and pallidigularis,

and another with a faster song comprised of harsher notes sometimes strung into

a longer rattle. This latter group is comprised of cervinigularis, hypophaeus,

and (to an extent) exsertus. In

listening to recordings, it does seem like exsertus

(https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/butfog4/cur/multimedia?media=audio) has consistently slower songs than cervinigularis/hypophaeus (https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/butfog9/cur/multimedia?media=audio) with a somewhat harsher quality to the notes (thus, very unlike the

South American group). Some recordings of cervinigularis/hypophaeus also have a two-parted aspect

to the song, with the note shape being distinctly different in the first half

of the song, and with the second half often trailing off into a long rattle.

Songs of the three Amazonian taxa (ochrolaemus, auricularis, and turdinus)

are remarkably constant across their range: https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/btfgle1/cur/multimedia?media=audio. However, pallidigularis adds

a bit of complexity to the matter. Recordings from the southern end of its

range in Ecuador closely resemble those of the Amazonian taxa (e.g. https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/140267791, whereas those at the

northern end of its range in eastern Panama and northwestern Colombia are a bit

faster (https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/60369, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/286906, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/610186681). That variation aside, there does seem to be a rather sharp break

between sweeter-sounding birds in the Canal Zone (e.g. https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/28412) and rattling birds in the far west of Panama on the Caribbean slope (https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/214530601). It is also possible that some of the recordings linked above are

after playback so the birds may be singing a more intense song, as at least

some recordings from the Canal Zone are slower and much more like Amazonian

birds (https://xeno-canto.org/448169).

Plumage:

David Vander Pluym was nice enough to photograph

a series of specimens of the taxa in this complex that are housed at the

Louisiana State University Museum of Natural Science (LSUMNS). Photos in

dorsal, lateral, and ventral views are shown below. In each photo, 2-3

individuals of each taxon are shown, with the taxon name written above, and the

red vertical lines separating the proposed species. The taxa from left to right

are: auricularis, ochrolaemus, turdinus, pallidigularis,

exsertus, hypophaeus, and cervinigularis.

Ridgway (1911) had some insights into the

plumage and morphometrics of this complex. As is noted above, he recognized

three species in the group, although these are not the arrangement that is

currently being considered, it is also not the broad polytypic circumscription.

Regarding cervinigularis, he noted:

“Mexican specimens

average decidedly deeper in color than others, especially the buff of

superciliary stripe, throat, etc., and brown of pileum, the latter almost sooty

in its darkness. Guatemalan examples have the back, etc., more rufescent or

castaneous, those from Honduras, British Honduras, and Nicaragua more

olivaceous than Mexican specimens. The series examined is, however, inadequate.”

For hypophaeus, he noted that it was “Similar

to A. c. cervinigularis but

coloration decidedly darker, especially under parts of the body, which are

isabella color medially darkening laterally into deep buffy olive, contrasting

strongly and abruptly with the buff or ochraceous-buff of chin and throat.” Ridgway (1911) considered specimens from Veraguas in western Panama

to be hypophaeus but had no samples

between there and the Canal Zone, which he considered pallidigularis. Thus, no specimens from the potential contact zone

were available to him. Regarding these samples of pallidigularis, he noted that it was “Somewhat

like cervinigularis but superciliary

stripe much less distinct (the supra-auricular portion more or less obsolete),

general coloration paler, feathers of chest without darker margins, and size

smaller.” Regarding exsertus,

which he considered a subspecies of A.

pallidigularis, he said it was “Similar to A. p. pallidigularis but slightly

larger, with relatively longer bill, color of back, etc., more olivaceous,

chest uniform in color, and buff of throat, etc., deeper.”

All of Ridgway’s comments seem (unsurprisingly)

consistent with the patterns shown in the photos above. Plumage is clearly

conserved across the group, with more intra-specific (if the split is adopted)

than inter-specific plumage variation. To my eye, the pale throat of pallidigularis really stands out, as do

the generally warmer underparts of cervinigularis.

However, other characters like bill size, degree of mottling on the chest, and

intensity of the olive below, all seem to vary.

Cory and Hellmayr (1925) merged all taxa into a

polytypic A. ochrolaemus, which seems

to be the basis for much of the modern treatment of the group until exsertus was elevated to species rank by

NACC. Although they did not elaborate on the decision to merge all these taxa

into one species, the following footnote for pallidigularis is of particular interest:

“It will be remembered that Salvin and Godman (Biol. Centr.-Americ,

Aves, 2, p. 158, 159) record both A.

cervinigularis and A.

"pallidigularis" from the Veraguas. Although no specimens are

available I have little doubt that all the birds of that region will ultimately

prove to belong to A. o. exsertus.

One of our Bogava skins, by reason of its distinct postocular stripe and

decidedly rufous under tail-coverts, closely approaches the eastern hypophaeus, and it is probable that

similar examples (which obviously represent only the extreme of individual

variation) have given rise to the reported occurrence of “cervinigularis" in the Veraguas.”

Bogava is in the

lowlands of Chiriquí, well within the range of exsertus. If I am interpreting this passage correctly, Cory and

Hellmayr (1925) are suggesting that exsertus

from the far east of its range might approach hypophaeus in plumage. There are low passes over the Talamancas in

this region, and it is possible that the two taxa might locally be in secondary

contact.

Recommendation: I very tentatively recommend a YES vote on splitting cervinigularis from ochrolaemus, which would bring us in line with WGAC. The vocal

differences between the cervinigularis

group and the ochrolaemus group are

certainly much greater than those that led to the split of exsertus from cervinigularis.

However, those taxa are allopatric and had good data on vocal discrimination,

whereas cervinigularis and ochrolaemus are certainly in contact in

west-central Panama but without any data from the contact zone.

The split then rests on two primary factors: the

primarily mitochondrial gene trees showing a close relationship between cervinigularis and exsertus (thus rendering ochrolaemus

sensu lato paraphyletic if it

includes the cervinigularis group)

and the very qualitative assessment of vocal differences included here. Those

two factors are admittedly quite highly differentiated, and more so than are

the differences that led to the split of exsertus.

WGAC used this same reasoning to strongly advocate for the split of cervinigularis.

WGAC adopted the English common names of

Fawn-throated Foliage-gleaner for A.

cervinigularis and Ochre-throated Foliage-gleaner for A. ochrolaemus, and if the split passes I recommend that we follow

suit. Because this is a parent-daughter split (mostly, anyway), new names

should be adopted for the daughter species and Buff-throated should be

abandoned. I note, however, that Ridgway (1911) used Buff-throated for cervinigularis sensu stricto. ‘Cervinus’ refers to ‘stag-like’, hence the common

name of Fawn-throated, which I think is a good name. Ochre-throated also

parallels the scientific name for ochrolaemus

and is similar to the “Ochraceous-throated” used by Cory and Hellmayr (1925).

Ridgway (1911) used Pale-throated for pallidigularis

sensu stricto, which is an

appropriate name if that taxon is eventually elevated to species rank.

Literature Cited:

Birds of the World. 2023. Edited by S. M. Billerman, B. K. Keeney, P. G.

Rodewald, and T. S. Schulenberg. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY,

USA. https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/home.

Claramunt, S., Derryberry, E.P., Cadena, C.D., Cuervo, A.M. Sanín, C.,

and Brumfield, R.T. 2013. Phylogeny and classification of Automolus foliage-gleaners

and allies (Furnariidae). The Condor, 115(2), 375–385, https://doi.org/10.1525/cond.2013.110198

Cory, C. B. and Hellmayr, C. E. 1925. Catalogue of Birds of the

Americas, pt. 4. Field Mus. Nat. Hist. Zool. Ser. 13: 1–390.

Harvey, M.G., et al. 2020. The evolution of a tropical biodiversity

hotspot. Science 370,1343-1348. DOI:10.1126/science.aaz6970

Ridgway, R. 1911. The Birds of North and Middle America, part 5. Bull.

U.S. Nat. Mus. 50: 1–859.

Schultz, E.D., Burney, C.W., Brumfield, R.T., Polo, E.M. Cracraft, J.,

Ribas, C.C. 2017. Systematics and biogeography of the Automolus infuscatus complex (Aves; Furnariidae): Cryptic diversity

reveals western Amazonia as the origin of a transcontinental radiation.

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 107: 503-515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2016.12.023.

Smith, B., McCormack, J., Cuervo, A. et al. 2014. The drivers of

tropical speciation. Nature 515, 406–409. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13687.

Oscar Johnson, May 2025

Note from Remsen on English names: If the proposals pass, I see no immediate reason for us to meddle with

English names already chosen by NACC (Chiriqui Foliage-gleaner and Fawn-throated

Foliage-gleaner), but if someone objects, speak up and be prepared to write

separate proposals.

Vote tracking chart:

https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart1044+.htm

Comments

from Remsen:

“A.

[taken from his comments on the original NACC proposal]: YES. Discrimination in playback trials usually

correlates with assortative mating and absence of free gene flow, and so I

interpret these data as showing that these two taxa have differentiated to the

point associated with barriers to gene flow between parapatric/sympatric

species. No one who does playback trials

thinks that this is directly equivalent to mate choice, but rather that it is

an index of potential gene flow if the two were in contact based, empirically,

on many examples that go both ways, i.e. taxa that do not mate assortatively

show strong playback responses, and those that do mate assortatively show low

levels of response. All of this is

discussed in detail in various papers using playback trials. In the imperfect world of assigning taxon

rank to allotaxa, use of playback trials is one of the stronger tools we have,

for better or worse. Much of our current

taxonomy is based on playback trials or degree of divergence in vocal

characters. That professional and

amateur ornithologists worldwide use tape playback to find particular species

provides testimony to the common sense behind interpretation of playback as a

determinant of taxon rank.

“Of

course, in a perfect world we would wait for comparable data between other taxa

in the ochrolaemus complex, but

without a guarantee that such a project is underway, I favor endorsing this

split now. Perhaps this will catalyze

work on other members of the group.

“There

seems to be confusion in terms of what the proposal actually proposes. As in the Recommendation, the allopatric

population of the Chiriquí lowlands is proposed as a separate species, A. exsertus (Chiriqui Foliage-gleaner)

from all other populations of A.

ochrolaemus. As for Pam's question

on whether they are truly allopatric, I assumed that this is the case because

these birds don't get higher than 1400 m, but I have now checked with César

Sánchez (who is doing his dissertation on birds of this region of endemism),

who confirms that they are allopatric as far as is known. The reason hypophaeus remains associated with A. ochrolaemus s.l. is that it is parapatric with other subspecies

treated within A. ochrolaemus; these

form a nearly contiguous set of 3 subspecies that extend from SE Mexico through

Panama across N Colombia. Then, there is

a gap between those populations and the 3 subspecies east of the Andes in

Amazonia, and as noted by Pam, that's where a big change occurs in song. That

the song of hypophaeus may or may not

be closer to nominate ochrolaemus or

other subspecies is a separate issue that should be addressed in future research. As Cadena and Cuervo have shown with Arremon brush-finches in the Andes,

geographic patterns in song variation can show a leapfrog pattern, so

comparisons of these two Costa Rican taxa to the rest of the complex must be

done comprehensively.”

“B. NO,

reluctantly. I can see why Oscar’s recommendation was highly tentative, and I

wonder if WGAC had not already voted on this whether the recommendation would

be different. Using a mtDNA gene tree to

infer phylogeny (from Smith et a. 2014) is just not scientifically valid in

2025, in my opinion. As for the voices,

I can hear a difference, of course, between the few linked recordings. But we’ve debated about with Boesman’s published

analyses were sufficient for taxonomic decisions, so how can we make a taxonomic

decision based, in my opinion, solely (given uncertainty of mtDNA gene tree) on

a couple of recordings without knowing the full variation represented across

the ranges of these taxa? As a matter of

principle, I think we should require better scientific evidence to change the

status quo, even if the status quo is insufficiently grounded in data. This does not mean that I interpret the

current data as indicating BSC conspecificity but rather than the data so far

are inadequate for making a change.

“The two dissenting NACC voters

made these points independently and were not willing to vote for a split based

on a gene tree and unpublished qualitative assessment of a few sonograms. Both emphasized the need to study the contact

zones.”

“The big problem with a NO on this

is that it would leave our broadly ochrolaemus as paraphyletic with

respect to exsertus if the gene trees of Smith et al. (2014) and Schultz

et al. (2017) are species trees; however, I would maintain that whether these gene

trees reflect species trees requires further data, and I would prefer to

maintain a potentially paraphyletic ochrolaemus until those data are

available. I suspect this will be

resolved soon with genomic data from the Harvey lab or elsewhere.”

Comments from Robbins: “

“A. YES. This appears

to be a straightforward decision given playback and genetic data, so a YES for

the split.

“B. YES. Given what we

know, this certainly is more problematic than the recognition of exsertus

as a species because of the lack of vocal data as well as not knowing what

interactions occur in an apparent contact zone between cervinigularis

and ochrolaemus in west-central Panama. Nonetheless, genetic data

(granted only mitochondrial data and we know how misleading that can be) from

two separate studies indicate that cervinigularis appears to be sister

to exsertus. So, if we take those genetic data at face value and

recognize exsertus I think we should go ahead and recognize cervinigularis.

Clearly, additional data may dictate a reevaluation.”

Comments from Lane: “YES to A to align with NACC. I

am further persuaded also to vote YES to B. Vocally, it is obvious that the

Middle American group (cervinigularis/exsertus) is worlds apart

from the South American group (ochrolaemus), and notably, the Chocó

population sounds like the cis-Andean birds and very unlike the Middle American

cervinigularis, not following the usual trend of the Middle American

clade extending to the Chocó. In Panama, I am interested to hear that the song

of pallidigularis is considerably faster than that even from the Chocó.

This is intriguing, but there seems to be a sharpish break between Veraguas and

Panama provinces (the closest recordings I can find between the hypophaeus

and pallidigularis groups, both from Macaulay). I’m hard-pressed to

believe that there is some sort of cline or interbreeding happening in that

zone. Unlike the Troglodytes aedon case, these are suboscines, so

dialect-forming is not likely and the distinctions between the voices are

almost certainly reflected in the phylogenetics, for which we have an mtDNA

tree. It would be nice to have this resolved more explicitly, but I am satisfied

with the combination of datasets we have now to agree to this split.”

Comments from Areta: “When working for AviList/WGAC, I realised

that the 2-way split adopted by eBird, IOC, and NACC seemed problematic, and I

made the following comments on the 13th of December 2022 (synthesized here):

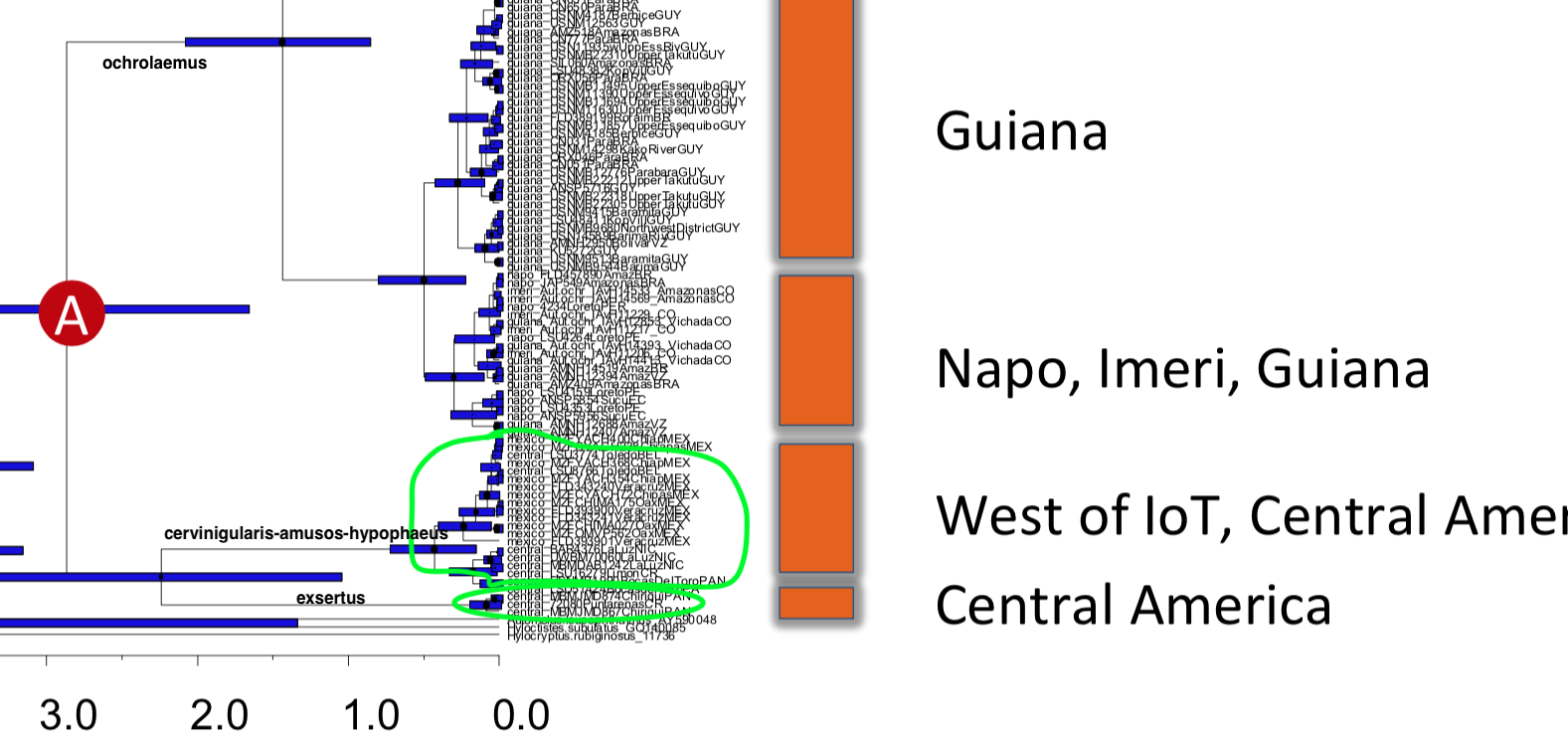

"Wait, if I understand

this correctly, this two-way split would mean two

unacceptable things:

“1) That A.

ochrolaemus would be deeply paraphyletic (because we would be

including the "cervinigularis-amusos-hypophaeus" group with A. ochrolaemus, but it is

sister to exsertus.

See zoom into the image that

Tom posted from Smith et al. 2014:

“2) That A.

ochrolaemus would also be vocally very divergent, with two vocal

types clearly identifiable: again, the "cervinigularis-amusos-hypophaeus" vocal type (i.e.,

Mexican) and the nominate ochrolaemus

group (i.e., ochrolaemus-pallidigularis-turdina-auricularis).

--- Take a listen here

“I must say that exsertus and cervinigularis-amusos-hypophaeus

sound more similar among them than to the ochrolaemus

group, exactly as portrayed by the phylogenetic relationships. Listen to exsertus here.

“I cannot access the

comments of the NACC votes (I went through the proposal only).

“I would

therefore vote NO to the two-way split but would be happy to go with a

three-way split, which is consistent with

vocal differentiation and phylogenetic relationships. Either I missed the plot

here, or people have been uncritical to details. I confess that the 3-0

football match today might have had an effect.

“My feeling is that the 2-way split got momentum

because Freeman & Montgomery just did playbacks between two groups."

“I only see a single option here, and it is to adopt

a 3-way split that is consistent with what we know of vocalizations (even

without a formal analysis), and which is also in agreement with available

phylogenetic data:

A-YES

B-YES”

Comments from Stiles: “A. YES to split exsertus;

B. YES to split cervinigularis/hypophaeus from ochrolaemus

(thus 3 species: cervinigularis, exsertus, ochrolaemus).”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“A.

YES. I actually did a lot of

investigation into species-limits in the Automolus ochrolaemus

complex dating back to the 1990s and early 2000s, including borrowing lots of

specimens of all of the named subspecies to measure, photograph and examine

plumage differences. At the same time, I

accumulated an archive of sound recordings from the various taxa to supplement

my own extensive recordings. Alas, this

was one of many such projects that ended up on the back burner as other work

and life priorities took over, and I never got to the stage of writing anything

up, let alone publishing. However, I do

have a lot of pertinent background with this group to bring to the table in

terms of evaluating these Proposals. The

thing that initially stimulated me to investigate species-limits in this

complex, were the vocal differences that I noted between exsertus and hypophaeus

in Costa Rica (and, more broadly, between these Central American birds and all

Buff-throated Foliage-gleaners that I encountered throughout Amazonia and the

Guianas). These differences in song,

although somewhat subtle, were consistent between the Caribbean Slope and

Pacific Slope populations, and that prompted me to conduct playback trials

between the two taxa similar to the ones conducted by Freeman and Montgomery,

2017), nearly 2 decades later. I

conducted the playback trials on hypophaeus from various Caribbean Slope

sites, but primarily from La Selva OTS station and Braulio Carrillo NP. My playback trials on exsertus were

primarily from Las Cruces OTS station (Wilson Botanical Garden) in Costa Rica,

and various sites in Chiriqui Province of western Panama (Pacific Slope). I don’t have access to any of my actual data

at the moment (I’m out of state on vacation as I type this), but I can report

that I had no instances in which individuals of hypophaeus responded to

playback of exsertus, nor any instances in which any exsertus responded

to playback of hypophaeus. There

were rare instances in which an individual Automolus would also exhibit

no appreciable response to playback of same-taxon vocalizations, but in the

vast majority of all trials, foliage-gleaners did respond strongly to playback

of same-taxon songs, while ignoring playback of the allopatric taxon. As such, all of my personal experience with

these two taxa, obtained over 35 years or so of fieldwork in Costa Rica and

Panama, squares with the more systematically conducted and published playback

trials of Freeman & Montgomery (2017), and I strongly agree with their

conclusion and the recent move by NACC to treat exsertus as a separate

species from hypophaeus, and, by, extension, from the remainder of the A.

ochrolaemus-group (more on that in my Part B comments).

“B.

YES. All of my unpublished work on the

complex indicated significant vocal differences between the northern cervinigularis-group

(including hypophaeus) and everything else to the south/east in the

complex, and, as Mark notes, genetic data from two separate studies indicates

that cervinigularis is sister to exsertus. The vocal distinctions

between the cervinigularis-group and the South American ochrolaemus-group

are much greater than the differences between cervinigularis and exsertus,

so much so, that I don’t think we really need a quantitative analysis to rely

upon, given the large number of publicly archived recordings available for

examination. As Dan alludes to, the case

with pallidigularis is particularly interesting. Not only is it vocally closer to the

cis-Andean South American birds than to Middle American cervinigularis,

but it is distinctly whiter-throated than either the northern group of taxa or

the South American group of taxa. Of

particular note, and, again, I am fuzzy on specifics and will have to dig up my

recordings when I’m home, I have a strong recollection of being very excited to

obtain audio recordings of two different vocal types (the normal pallidigularis,

as well as a hypophaeus sounding and looking bird) from the Nusagandi region of San Blas Province sometime prior to

2010. This would establish sympatry

between the two taxa, something I have always meant to follow up on, as part of

the bigger project. At any rate, I think

there’s a decent chance that pallidigularis may prove to be distinct

from the ochrolaemus-group, but I feel confident that it and all of the

South American taxa are different from the cervinigularis-group.

“I

would also agree with Van’s suggestions regarding

English common names if both splits pass (Fawn-throated for cervinigularis;

Ochre-throated for ochrolaemus), and also reserving Pale-throated for pallidigularis,

should that taxon ever be split in the future.”

Comments from Bonaccorso: “A and B: NO. As noted above, it

is logically inconsistent to accept A but reject B, because accepting A alone

would render A. ochrolaemus paraphyletic. The options are therefore to

accept both A and B or reject both.

“The playback experiment offers strong support for the separation

implied by A. However, beyond this result, the remaining arguments rely

primarily on a mitochondrial gene tree, which is not sufficient evidence on its

own. The vocal data is anecdotic and the differences in plumage are so subtle

that it is very difficult to decide based on those lines of evidence.”

“Although I personally suspect that three species are involved, an

integrative taxonomic framework requires multiple independent lines of solid

evidence. At present, the data do not adequately support a three-way split, and

I do not see a compelling reason to rush this decision just to align with WGAC.”

Comments from Naka:

“A: YES. The evidence is compelling, and I am happy to split the

two forms based on song and DNA.

“B: YES, I also agree with the second split, avoiding creating a

monster A. ochrolaemus. I appreciate Nacho and Dan's comments on this

matter.”