Proposal (1058) to South

American Classification Committee

Treat the

spodionota subspecies group as a separate species from Silvicultrix

frontalis.

Effect

on SACC:

This would split an existing species on the SACC list into two species.

Introduction: SACC has been asked

to do this proposal because the IOC list treats them as two species, citing

Moreno et al. (1998) for support.

However, they are treated as conspecific by Clements, Howard-Moore, and

HBW-BLI lists. I did not have this issue

on our proposal “do list” because it is based largely on Moreno et al.’s

comparative genetic distance using mtDNA sequence data (350 BP ND2).

Our

current SACC note reads:

120. García-Moreno et al. (1998)

suggested that the plumage and genetic differences between the frontalis

and spodionota subspecies groups warranted species-level recognition for

each.

Background: Silvicultrix (ex-Ochthoeca)

frontalis has traditionally been treated as a single species that occurs

in the humid Andes from n. Colombia to c. Bolivia, e.g., from Cory &

Hellmayr (1927) through Meter de Schauensee (1970) and Fjeldså & Krabbe

(1990) to AviList (2025), with 3-5 subspecies:

• albidiadema:

Eastern Andes of Colombia

• frontalis:

Central Andes of Colombia south to western Andes in n. Ecuador, but see next:

{• orientalis}:

Eastern Andes from n. Ecuador to c. Peru (subsumed by Traylor [1985] into nominate

frontalis)

• spodionota:

Eastern Andes in c. Peru (Junín to n. Cuzco) but see next:

{• boliviana}:

curiously patchy and taxonomically “impossible” range, interrupted by spodionota:

Andes from c. Peru south to c. Bolivia; see Traylor (1985) for full details on

this taxonomic conundrum, but briefly, recognizing boliviana splits it

into two allopatric and evidently phenotypically indistinguishable populations,

but treating this as a synonym of spodionota makes the latter split into

3 populations with a leapfrog pattern of phenotypic variation, the central one

diagnosably different from the populations to north and south; then, there is

also the unnamed Cordillera Vilcabamba population, which according to Traylor

is the most distinctive of all with most individuals without wingbars … like

the frontalis group. Broadly

defined spodionota would thus be just as uncomfortable as recognizing

disjunct populations of boliviana as the same taxon in that it would

have four diagnosable populations, each possibly a PSC species. This one will be exceptionally interesting to

study genetically.

Traylor

(1985) provided rationale for their treatment as conspecific pending study of

the contact zone in central Peru.

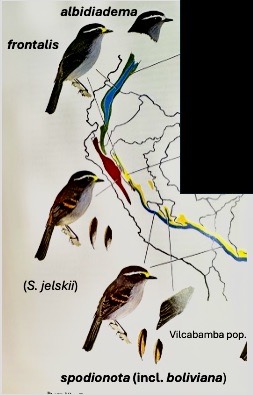

Below

is John Fitzpatrick’s plate from Traylor (1985 – the original is much better

than reproduced here). I have blacked

out Silvicultrix pulchella to reduced noise, but I have left in the

taxon jelskii of the western Andes of extreme s. Ecuador and nw. Peru;

currently treated as a separate species, it has been treated as a subspecies of

both S. frontalis and S. pulchella. Harvey et al. (2020) showed that it is sister

to S. pulchella, not S. frontalis/spodionota.

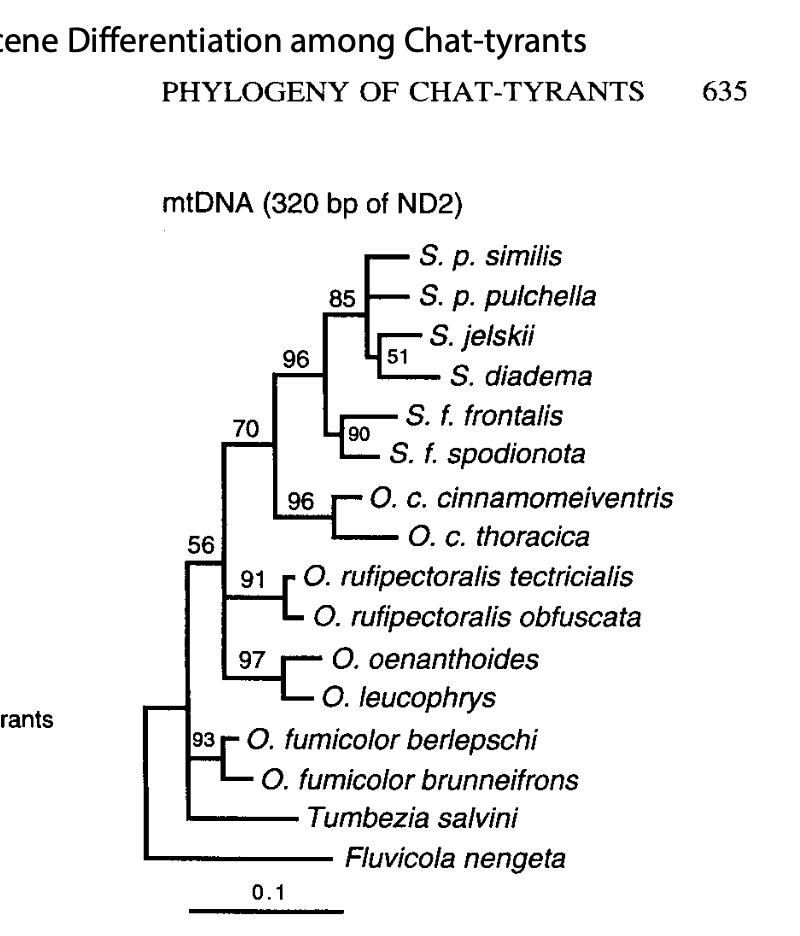

New information: Obviously not very new but García-Moreno et al. (1998) in a study of

the phylogeny of chat-tyrants used 320 bp on mtDNA (ND2) to produce the

following phylogenetic hypothesis:

This was 1998, so cut them a lot of slack on the

weak genetic sampling – this was top-of-the-line stuff back then. They showed that frontalis and spodionota

groups were sister taxa with modest support.

García-Moreno et al. (1998) argued for their treatment as separate

species based on comparisons of relative genetic distance, including alluding

to broader comparisons of many taxa of Andean forest birds.

As noted by Traylor (1985) and García-Moreno et

al. (1998), the putative contact zone between the northern frontalis

group and the southern spodionota group is somewhere in that 150 km long

region of Dpto. La Libertad from which there are almost no bird samples and in

which there are no known biogeographic boundaries (See recent SACC Pionus

proposal). Knowing what happens at the contact zone would presumably provide an

immediate “answer” to taxon rank in this case, i.e. abrupt turnover with little

sign of gene flow or a hybrid swarm. For

now, it’s anyone’s guess. The main

phenotypic difference is the absence (frontalis) or presence (spodionota)

of rufous wingbars.

Here is the rationale presented by García-Moreno

et al. (1998):

“Traylor (1985) identified a gap of 150 km

between the southernmost frontalis in La Libertad and the northernmost spodionota

a little north of the Huallaga Gap in Huánuco, and decided to treat them as a

single species until information was obtained about how they interact in a zone

of sympatry. This segment of the Cordillera Central remains poorly explored,

thus the taxa are recognized currently as subspecies. However, the genetic

differences between them (0.059, including 4 tv) is of a level comparable to that

of fully recognized species(e.g., S. diadema and S. jelskii:

0.063, O. leucophrys and O. oenanthoides:0.042; Table 1).

Although we do not think that species status can be diagnosed solely on the

grounds of a quantity of molecular or morphological divergence, we believe that

the mtDNA divergence together with biogeographic separation and plumage

differentiation suggest that they are different species: S. frontalis

(including subspecies albidiadema and orientalis) and S.

spodionota (including subspecies boliviana). It should be noted that

the Southern taxa (spodionota and boliviana) are phenetically

very similar to S. jelskii, whereas the northern S. frontalis

albidiadema is characterized by the absence of wingbars and rufous fringes

on the tertials (this could be a derived character state; however, a similar

lack of wing-pattern also is found within S. spodionota in western Cuzco

and Ayacucho).”

Discussion

As far as I can determine, there is no hint that

the two groups differ vocally, although this might be because there isn’t much

to work with. These birds are usually

silent, and their voice is a short trill.

Boesman did not attempt and analysis, and there is no hint in

Schulenberg et al. (2007) (or anywhere else I’ve looked) of vocal

differences. That of course does not

mean that critical differences don’t exist – only that we don’t know yet.

My superficial check using xeno-canto provide an

N=1 possibility that those differences exist:

The only recording in xeno-canto of the song of spodionota

group is a good one of boliviana from Dpto. La Paz by Dan Lane:

https://xeno-canto.org/species/Silvicultrix-spodionota

Note the separated notes at the end of the

trill.

In contrast, here is a typical song from the frontalis

group from Ecuador:

https://xeno-canto.org/species/Silvicultrix-frontalis

This represents is the way the song is usually

rendered phonetically in field guides.

Note the lack of separate notes at the end, which only has a slight

“hump” in the steady trill.

This has no meaning pending an analysis of a lot

more recordings, especially from the central Peruvian population of boliviana’s

range and, most critically, from spodionota itself, which would be the

type species if we recognized S. spodionota. At this point, for all we know there could be

different songs for Peruvian frontalis south of the Marañon, Peruvian boliviana,

spodionota, and Bolivian boliviana. Or no consistent variation at all.

Because voice is critical in species limits

assessments in the Tyrannidae, I do not think that there is any evidence to

change the status quo at this time. The

plumage differences are suggestive but not conclusive of anything beyond

subspecies rank. The genetic data (a

tiny BP sequence of one mitochondrial gene) is inadequate for making taxonomic

decisions of any kind. Thus, I strongly

recommend a NO on this based on current evidence. I also see no need to rush this because

eventually we will likely have conclusive evidence from the uncontacted contact

zone. Also note that the difference in

presence/absence of wingbars as a species-level character is rendered

problematic by the Vilcabamba population of spodionota, which lacks wingbars –

see plate above.

Literature Cited: (see

SACC Biblio for others):

GARCÍA-MORENO, J., P. ARCTANDER, AND J. FJELDSÅ. 1998.

Pre-Pleistocene differentiation amongst chat-tyrants. Condor 100: 629–640

https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=13795&context=condor

TRAYLOR, M.

A., JR. 1985. Species limits in Ochthoeca diadema

species-group (Tyrannidae). pp. 430-442 in "Neotropical

Ornithology" (P. A. Buckley et al., eds.) Ornithological Monographs No.

36.

Van Remsen, June 2025

Note from Remsen on English names: If the taxonomic proposal passes, then we’d need a separate English

name proposal. IOC retained “Crowned

Chat-Tyrant for the frontalis group even though it’s range is not substantially

larger than that of spodionota and used “Kalinowski’s Chat-Tyrant” for

the spodionota group.

Vote tracking chart:

https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart1044+.htm

Comments from Niels Krabbe (guest voter): “YES. I

see that the sequences used by Garcia-Moreno et al. (1998) have not been

uploaded to GenBank, which I find most unscientific. Also, the number of bp

compared is low for today's standards.

“However, Winger and Bates (2015) gave complete (1041 bp)

sequences for the same (ND2) gene for a number of specimens of frontalis (from

E Carchi, Imbabura, W Pichincha, and Morona-Santiago, Ecuador, and San Martín,

Amazonas, Cajamarca, Huanuco and Apurímac, Peru). I

took the trouble to compare these sequences.

“The difference between frontalis (from Ecuador and N Peru)

and spodionota (from Huánuco, Pasco and Apurímac) is as high as 6%.

Furthermore, sequences from spodionota from Huánuco/Pasco (Unchog,

Millpo) and Apurímac are virtually identical. Only the Millpo bird differs very

slightly (one transition in 1041 bp). Birds from both N and C Ecuador (E

Carchi, Imbabura, Cotopaxi, Morona-Santiago) are also virtually identical to

each other (Imbabura bird differs by one transition in 1041 bp), whereas they

differ from N Peruvian birds by about 1%. N Peruvian birds still differ from C

and S Peruvian birds by 6%.

“The distinct genetic and morphological difference between

frontalis and spodionota lead me to think it safe to rank them as different

species.”

Winger, B. M. and Bates, J. M.

2015. The tempo of trait divergence in geographic isolation: Avian speciation

across the Marañon Valley of Peru. Evolution 69 (3): 772–787.

Comments from Andrew Spencer: “I wanted to offer some unsolicited

comments on the Silvicultrix frontalis split proposal and add some

observations/quick analysis on the vocalizations of the two groups. Hopefully

this will add some information for those voting on the issue. None of this is

published of course, sample sizes are small, and geographic coverage not the

best, but here you go:

“Back when I was guiding in the Andes, I noticed while Ecuadorian

birds would often respond somewhat nicely to playback when I was trying to show

clients the species, those in central and southern Peru were much less

cooperative. Digging further after one frustrating experience, I realized all

the cuts I was using were from Ecuador, and so I found a recording (I don't

remember which at this point) of the southern population to try. Later in

the trip I used that recording, with the birds responding much better. This is

in spite of the overall vocalization sounding superficially quite similar. I

filed this away as "interesting, I'll dig into this later", and then

promptly forgot to do anything of the sort.

“On a post-guiding career trip to central Peru, I spent some more

effort trying to get recordings of chat-tyrants. I eventually managed to find a

couple of birds that were actually vocalizing naturally at dawn, seemingly

while having a territorial dispute. Unfortunately, they quickly became quiet,

and subsequent recordings I obtained were after playback. This did remind me

though that I needed to look into vocal differences between the northern and

southern groups, which I did at the time, but then again filed away under the

"someone should publish on this" excuse.

“So, all that said, I do think that at least some of the

vocalizations of the northern and southern groups of S. frontalis are

consistently and diagnostically different. I primarily looked at what I think

of a song in the species. There's always the risk that I'm not comparing

entirely analogous vocalizations, or that there is hidden complexity in the

repertoire muddying the picture that would become apparent with a larger sample

size. But I don't think that's the case here.

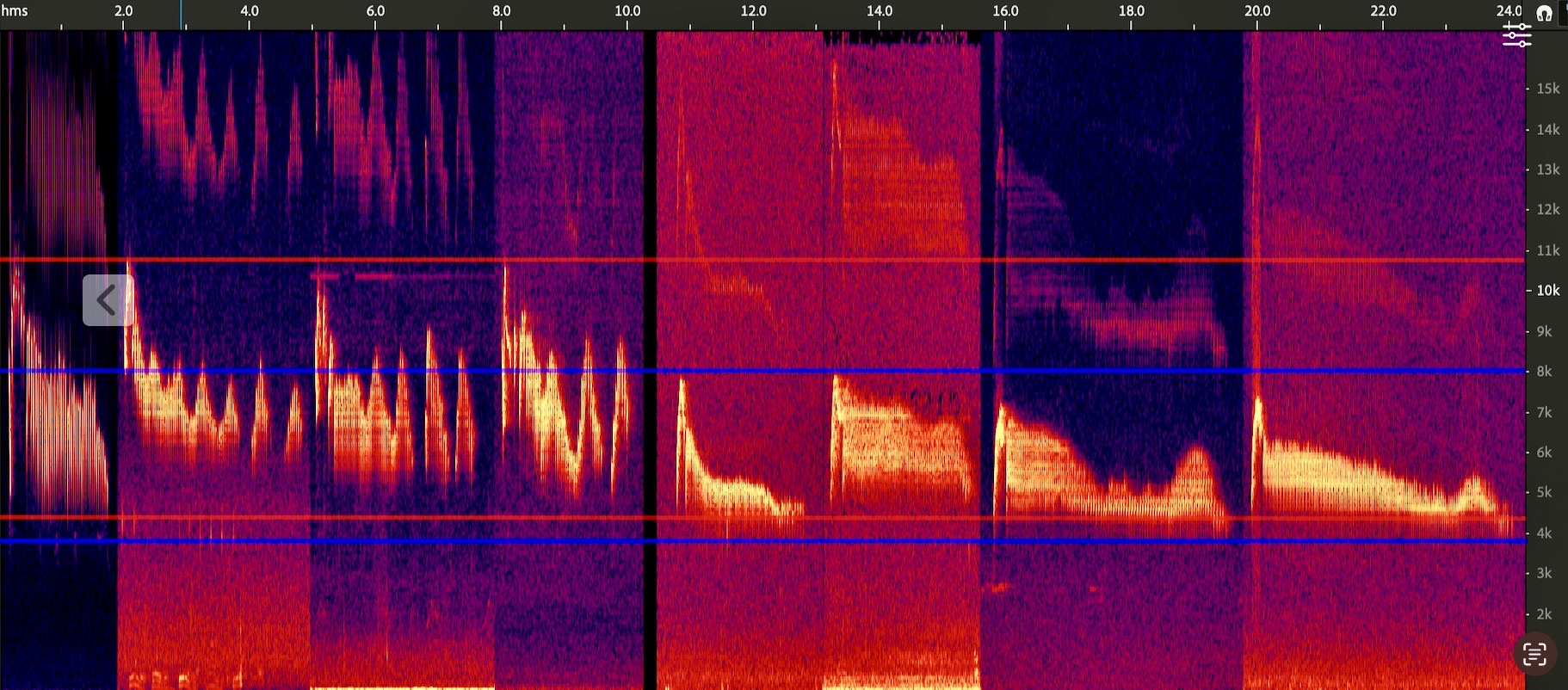

“To summarize, I think there are two (or three, depending how you

separate features out) important and consistent differences in the songs of

these taxa that are diagnostic.

“Van in his proposal has pointed out one difference: the

additional sputtering phrases after the initial longer trill. This is

apparently not always present (see the first example in the spec comparison,

below), but 3 of 4 samples I found do have it. Tied to this is the less regular

frequency pattern over the course of the song. The spodionota group,

while generally descending over the length of the song strophe, has a lot of

ups and downs. In the frontalis group, the song generally descends much

more smoothly, before having the slight "hump" noted by Van near the

end of the song.

“The other important difference is the overall pitch of the song,

especially the intro notes. These are notably higher-pitched in the spodionota

group than in the frontalis group. In the spec below, I have red

horizontal lines covering the highest and lowest frequencies in the spodionota

group, and blue lines doing the same for the frontalis group. Note how

the peak of the intro notes for spodionota are around 10.5-11 kHz,

whereas those of frontalis are between 7.5-8 kHz. Also note how the

majority of the energy in the song strophes averages quite a bit higher for

the spodionota group - in most samples almost entirely above

the song of the frontalis group.

“There are all the usual caveats for these poorly recorded birds,

including that it's unknown what happens in the gap between the northernmost

recording of the spodionota group in Huánuco and the southernmost of the

frontalis group in Amazonas. That said, in my opinion, the combination

of plumage differences, molecular data, even if rather dated, and vocalizations

all support a split.

“Recordings used in the spec comparison, left to right:

spodionota group:

ML633678529, Huánuco, Peru

ML470360571, La Paz, Bolivia

ML470352611, Cuzco, Peru

ML143651, Cuzco, Peru

frontalis group:

ML222114391, Pichincha, Ecuador

ML44533211, Imbabura, Ecuador

ML58284, Carchi, Ecuador

ML269800, Caldas, Colombia

Comments from Lane: “NO. This

is another case of a very weak study suggesting an interesting taxonomic puzzle

without providing enough evidence to clarify what is actually going on.

Garcia-Moreno et al. simply didn’t have enough sampling to make much sense of

the variation within S. frontalis, and an mtDNA study with 320 bp is

very little information. I will vote NO on this simply because the study simply

doesn’t offer much to vote on!

“My voice comparisons have been

strictly with the drawn-out trilled vocalization. This vocalization is what I

term the “daytime song” which is not the same as the dawn song that seems to

dominate in many Silvicultrix recordings by most other field-workers,

and it consists of single “tink” notes. I’ve made

efforts to record the daytime songs of Silvicultrix whenever I can and

have learned that my comments in Birds of Peru are not accurate (and were

written as a result of my ignorance some 20 years ago). With regards to voice,

my observations largely agree with what Andrew Spencer has written, although I

believe that bolivianus is distinctive within the southern group. See

recordings here: https://media.ebird.org/catalog?mediaType=audio&view=grid&taxonCode=crocht1https://media.ebird.org/catalog?mediaType=audio&userId=USER155017&view=grid&taxonCode=crocht1

and here: https://xeno-canto.org/species/Silvicultrix-spodionota

“Van mentions my cut from La Paz (https://xeno-canto.org/150430, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/638812141, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/470360571 all the

same cut, but the last is “unconfirmed” within eBird due to being on a

historical checklist that was flagged as too long by a reviewer), but I also

have recordings of the same song type from Manu Road in Cusco (https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/470352611) and

Cochabamba, Bolivia (https://xeno-canto.org/145014). So. I

think it’s safe to say that this song with the repeatedly rising-falling

terminal section is characteristic of S. f. boliviana and makes a case

for the taxon to be a good one (at least from Cusco south and east into

Bolivia). I have few recordings north of Cusco, and there are few others from

central Peru aside from Andrew’s and one or two more. These cuts suggest that

there is no rising-falling terminal section to the daytime songs of these

birds, but birds from Huánuco (https://xeno-canto.org/40518, and

Andrew’s cuts noted above) seem to be still higher-pitched and “weaker” than

those from Amazonas (https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/305709521, https://xeno-canto.org/131757 same cut

in both) and north of the Marañon (https://xeno-canto.org/704098, https://xeno-canto.org/5905, https://xeno-canto.org/121067). The

relative lack of samples makes it difficult to say much about the amount of

variation within and among individuals, so I will refrain from doing so.

Overall, my impression is that there is much more going on here than just

splitting S. frontalis into two, and the Garcia-Moreno et al. paper

simply doesn’t address the issue in any meaningful way. Until we have more

information, I think it best we wait for additional information (both

molecularly and voice) to make an educated decision on what’s going on here. To

split based on the current knowledge is a shot in the relative dark and may

result in something we’ll have to reverse as more information comes to light.”

Comments from Areta: “I vote YES to split spodionota

from frontalis. The congruent

genetic, plumage, and vocal data support the division. I would of course prefer

a proper taxonomic paper dealing with all the details and benefiting from more

samples, but the data seem enough to act. The unnamed Vilcabamba population is crying

out to be studied and named.”

Comments from Robbins: “Given

current information I’m on the fence on this one. Given that the plumage of

southern O. f. spodionota is more similar to S. jelskii

than nominate frontalis, yet Harvey et al (2020) have shown that the

latter is more closely related to pulchella, I consider plumage not to

be a good indication of relationships in Silvicultrix.

“The

ND2 data (thanks Niels for bringing in the additional information), are

suggestive, but I think most of us would agree that nuclear data are needed for

all Silvicultrix.

“With

regard to vocalizations, more information is needed, especially if perhaps some

of these comparisons are not of analogous vocalizations, e.g., dawn song vs.

post dawn song.

“I

think there may well be two species within the currently recognized frontalis,

but we need more information. So, for now I vote to wait until those data are

available.”

Comments from Stiles: “YES to split spodionota from

frontalis given recent genetic data, plumages, voice.”

Comments from Zimmer: “NO. Generally speaking, I’m a believer in the

axiom that “where there’s smoke, there’s fire”, and there is definitely some

‘smoke’ going on in this complex, as evidenced by the genetic data, and by the

vocal differences that Andrew Spencer has alluded to. But the vocal information presented to date

is mostly anecdotal, and the holes in the archived vocal samples are gaping, in

terms of both geographic/taxon coverage and sample sizes of apples-to-apples

comparisons of analogous/homologous vocalizations in these difficult to record

birds. The complexity of the situation,

both as regards the taxonomic conundrum presented by the spodionota-boliviana

situation, and, by the phenotypic conundrum presented by the Apurímac Valley

population of spodionota (which have either faint wingbars or lack them

altogether), which resemble frontalis more than they do spodionota,

suggests to me a fascinating evolutionary pattern, and one in which there may

be more than 2 species to emerge from this group when the dust settles. But for now, I’m with Dan, Van and Mark on

this one – we need more data to give a complete picture of what is really going

on, and I see no compelling reason to make a destabilizing partial move now,

one that may not actually advance the ball downfield, so much as kick it out of

bounds.”

Additional comments from Areta: "After reading Dan´s

comments (which I had not the benefit of reading before casting my vote) and Kevin´s

arguments, I switch my vote to NO. Things seem more complicated, and I look

forward to a study tackling this."

Comments from Claramunt: “YES. I think the combination of

plumage and genetic differences are sufficient evidence for the proposed split.

It may not be a simple situation, there may be more complexity understudied.

But splitting the complex into two, as proposed, seems a step forward. I don’t

see any evidence that these two taxa may be conspecific.”