Proposal (1059) to South

American Classification Committee

Recognize Patagona

gigas and Patagona peruviana as separate species, with revised

nomenclature

This

proposal would split the Giant Hummingbird (Patagona gigas) into two

species, the Northern Giant Hummingbird (Patagona peruviana) and

Southern Giant Hummingbird (Patagona gigas).

Background:

The

giant hummingbird genus Patagona has historically been treated as a

single species, Patagona gigas, with two subspecies: P. g. peruviana

(thought to range from Ecuador through NW Argentina) and P. g. gigas

(thought to range throughout Chile and to central Argentina, primarily).

Multiple recent studies have now provided strong, integrative

evidence––including genomic, morphological, ecological, biogeographic, and

vocal data––supporting full species status for these taxa; these studies

additionally clarify the ranges of each giant hummingbird form. A brief summary

is provided by Schulenberg et al. (2025).

New

Information:

This

history of the taxonomy and nomenclature of the giant hummingbirds was reviewed

in detail by Williamson et al. 2025, Zoological Journal of the Linnean

Society. Williamson et al. 2024, PNAS provided comprehensive

genomic, morphological, and ecological evidence of species-level divergence.

Newly available bioacoustic data analyzing songs across the ranges of both

lineages (Robinson et al., In Review; bioRxiv preprint: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.06.30.662449v1) documents striking

vocal divergence, providing additional decisive support.

Specifically,

these new data include:

Divergent

genomes:

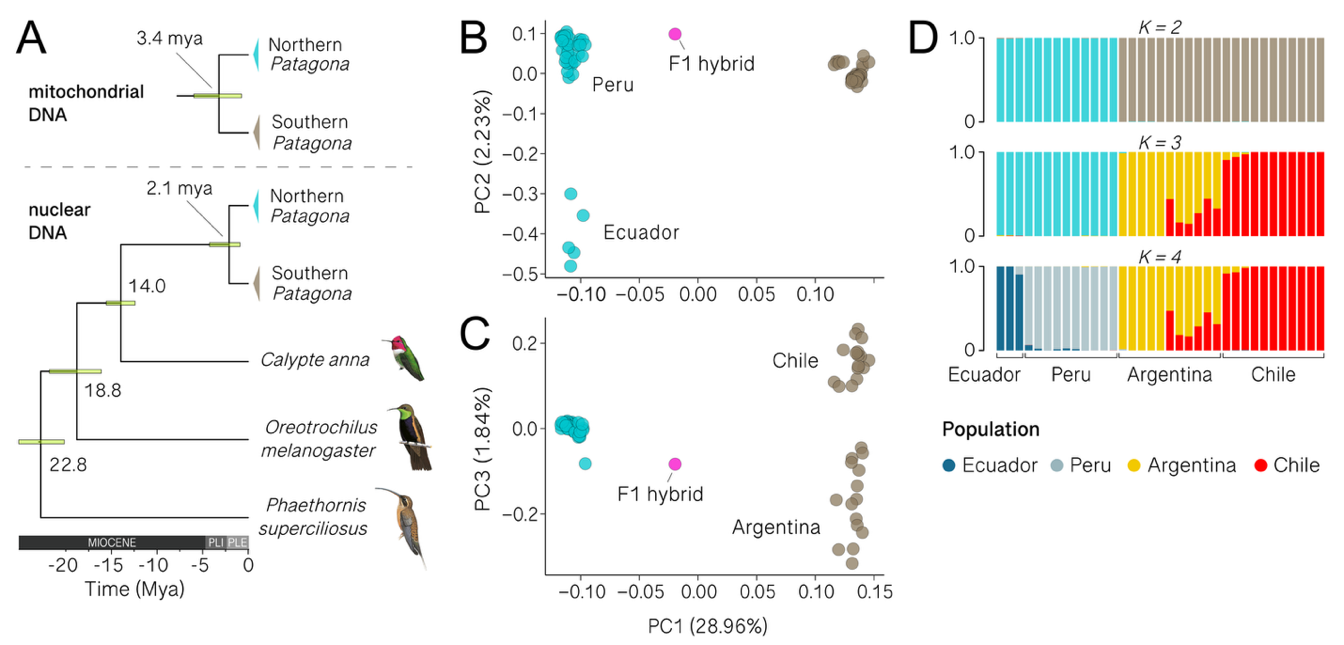

- Genome-wide divergence between peruviana

and gigas populations was high (FST ≈ 0.6), with

estimated divergence times of ~2.1–3.4 Mya, based on separate estimates from

nuclear DNA and mitochondrial DNA, respectively (Fig 1A; Williamson et al.

2024).

- Admixture and PCA analyses of the nuclear

genome showed clear population clusters with no evidence of ongoing gene flow.

The lack of gene flow over time was corroborated by ABBA/BABA tests (Fig 1B–D).

Hybridization:

- The one hybrid individual that was detected

among 101 sampled individuals was an F1 (from the non-breeding season zone of

range overlap in Peru). This finding indicates that there is nearly complete

post-zygotic reproductive isolation (Williamson et al. 2024), despite

incomplete pre-zygotic isolation and occasional hybridization between the two

species.

- There is no evidence of ongoing backcrossing

or introgression. If inter-species gene flow were occurring, backcrossed

individuals of mixed ancestry would outnumber F1s, but the population genomic

data presented in Williamson et al. (2024) clearly refute that possibility.

Figure 1. Genomic divergence of the giant

hummingbirds. A) Time-calibrated phylogenies estimated divergence of northern (peruviana)

and southern (gigas) giant hummingbirds ~2.1–3.4 million years ago

(Mya). B–C) Principal Components Analysis (4,416 SNPS from ultra-conserved

elements of 70 individuals) illustrated strong species differentiation and

structure within each northern and southern forms. D) Admixture analysis (with

sNMF) of 35 whole genomes illustrated clear population structure between

northern and southern forms. No admixed individuals were detected between

northern and southern lineages. Country labels denote sampling origin; colors

correspond to ancestry. Modified from Williamson et al. 2024.

Figure 1. Genomic divergence of the giant

hummingbirds. A) Time-calibrated phylogenies estimated divergence of northern (peruviana)

and southern (gigas) giant hummingbirds ~2.1–3.4 million years ago

(Mya). B–C) Principal Components Analysis (4,416 SNPS from ultra-conserved

elements of 70 individuals) illustrated strong species differentiation and

structure within each northern and southern forms. D) Admixture analysis (with

sNMF) of 35 whole genomes illustrated clear population structure between

northern and southern forms. No admixed individuals were detected between

northern and southern lineages. Country labels denote sampling origin; colors

correspond to ancestry. Modified from Williamson et al. 2024.

Morphology

& plumage differences:

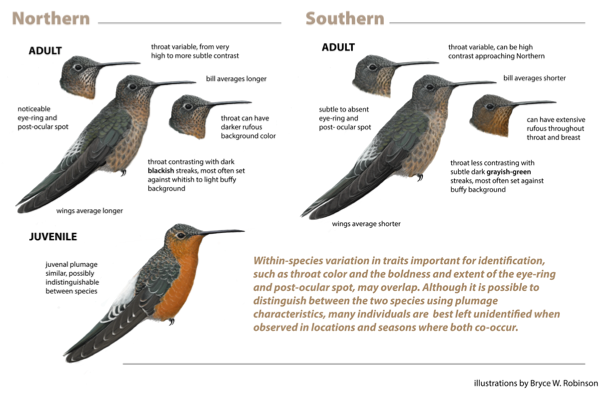

- peruviana averages larger in bill,

wing, tail, and tarsus length. It has a whiter throat and chin with darker

black streaks and a brighter white post-ocular spot (Fig. 2).

- gigas averages slightly smaller in all

measurements. It has a browner, sometimes reddish chin and throat, with almost

greenish streaks (Fig. 2).

- Despite these differences, extensive overlap

exists in morphological measurements; discriminant analyses based on morphology

can only correctly classify ~65–85% of individuals when evaluating solely

adults, and when examining sexes separately (Williamson et al. 2024, Williamson

et al. 2025).

Figure 2. Plate for distinguishing between

northern (peruviana) and southern (gigas) giant hummingbirds,

highlighting important plumage and morphological characteristics. Modified from

Williamson et al. 2025.

Figure 2. Plate for distinguishing between

northern (peruviana) and southern (gigas) giant hummingbirds,

highlighting important plumage and morphological characteristics. Modified from

Williamson et al. 2025.

Song

divergence:

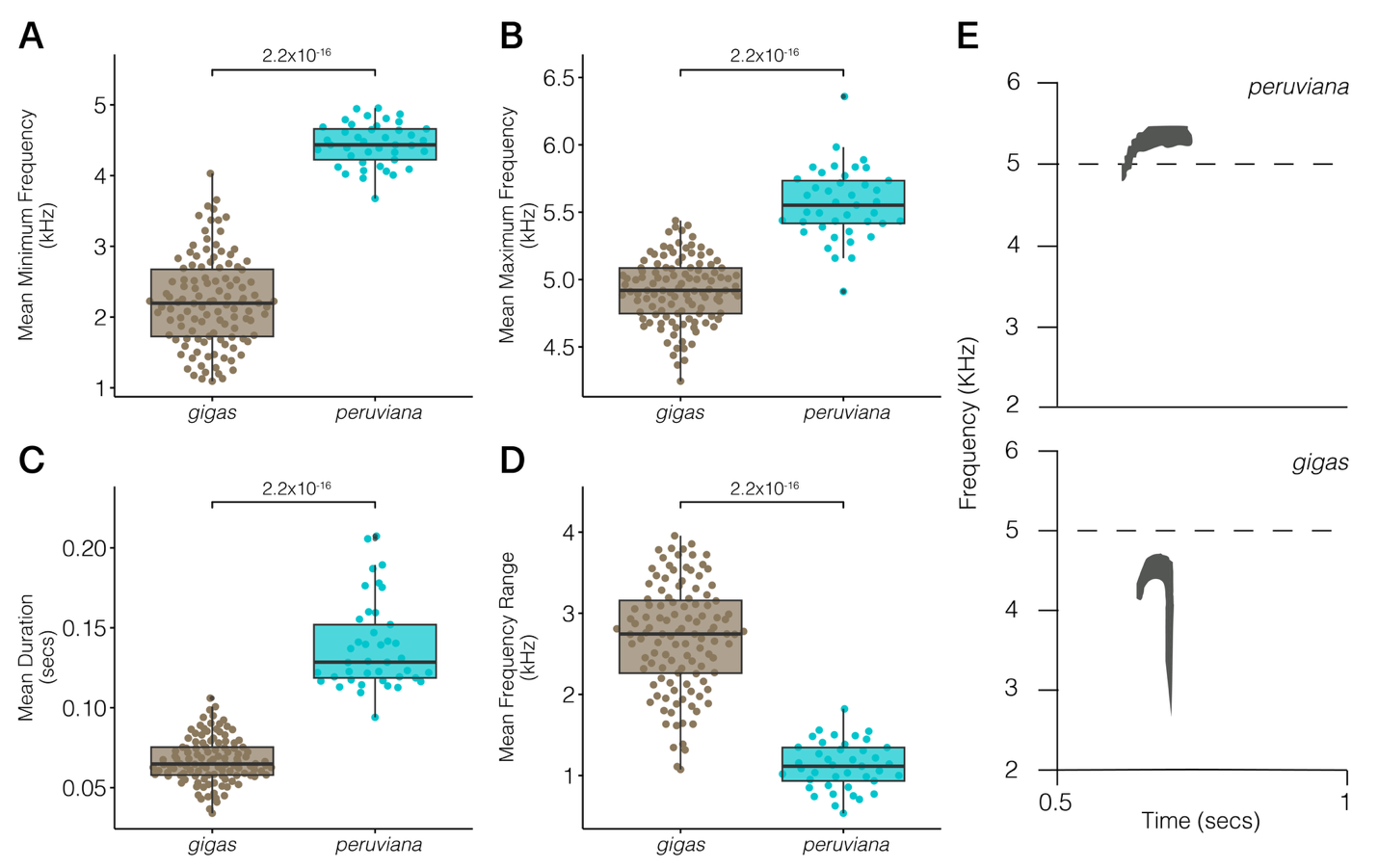

- A comprehensive analysis of 217 recordings

spanning 49 years (1976–2025), >36° latitude, and >4,300 m in elevation

has revealed that the songs of peruviana and gigas differ

significantly in all measured traits: peruviana songs are >2x longer

in duration with significantly higher minimum (mean ~4.5 kHz) and maximum (mean

~5.6 kHz) frequencies. The frequency range of gigas songs is 2x greater

than that of peruviana (Fig. 3A–D; Robinson et al., In Review).

- A linear discriminant model based on song

traits correctly classified individuals as peruviana or gigas

with 100% accuracy when trained on breeding season data. When applied to full

annual data as a tool to identify individuals across the range and during

periods of non-breeding season overlap, the model had 98.7% accuracy (1.28%

error rate; one individual mis-identified).

- Spectrogram shapes are highly diagnostic: peruviana

songs appear as an upward-sloping note leading to a short, horizontal segment.

By ear, songs are recognizable as a high-pitched, dry and thin 'tsee!'. In

contrast, gigas songs have the shape of a candy cane (i.e., an inverted

capital letter ‘J’; long and straight on one end, with a tight, curved bend at

the top). By ear, they are recognizable as a loud ‘tsiP!’ with an abrupt

ending.

- Song appears to be the most reliable and

diagnostic trait for field identification in zones of sympatry. Unlike plumage

and morphology, this characteristic is applicable to both adults and juveniles

(Fig. 3E).

Figure 3. The songs of northern (peruviana)

and southern (gigas) giant hummingbirds differ in all measured

characteristics. A) Minimum frequency was 2x higher in peruviana songs.

B) Maximum frequency was 1.3x higher in peruviana songs. C) peruviana

songs are 2x longer. D) Frequency range was 2.41x greater in gigas. E)

Spectrograms illustrate vocal differences between peruviana (top) and gigas

(bottom) songs; these differences diagnose the two with high confidence.

Modified from Robinson et al., In Review.

Figure 3. The songs of northern (peruviana)

and southern (gigas) giant hummingbirds differ in all measured

characteristics. A) Minimum frequency was 2x higher in peruviana songs.

B) Maximum frequency was 1.3x higher in peruviana songs. C) peruviana

songs are 2x longer. D) Frequency range was 2.41x greater in gigas. E)

Spectrograms illustrate vocal differences between peruviana (top) and gigas

(bottom) songs; these differences diagnose the two with high confidence.

Modified from Robinson et al., In Review.

Biogeography

& contact zone:

- peruviana is resident at high

elevations (1,800–4,300 m) from SW Colombia through Ecuador, Peru, northern

Chile, and into northern Bolivia.

- gigas is a migratory breeder in

central Chile (0–2,500 m) and NW Argentina (typically above ~2,500 m) that

spends the non-breeding season at high elevations (>2,500 m) in central and

southern Peru. It also breeds throughout Bolivia, where there are no data yet

on seasonal movements.

- New field data documented a previously

unrecognized sympatry around Copacabana, Bolivia (Lake Titicaca), where both

species co-occur at high elevations (Robinson et al., In Review).

- Songs are fully diagnostic, even in the

putative zone of sympatry.

Recommendations:

This

proposal has three parts:

A.

Species Recognition: Recognize the giant hummingbirds as two species

based on concordant genomic, morphological, ecological, biogeographic, and

vocal evidence (Robinson et al., In Review; Williamson et al. 2024;

Williamson et al. 2025).

B.

Scientific Names: Following the recommendations outlined in Williamson et

al. 2025, use the scientific name Patagona peruviana (Boucard 1893;

priority name, Areta et al. 2024) for the northern species and the name Patagona

gigas (Vieillot 1824) for the southern species. The name Patagona chaski

(sensu Williamson et al. 2024) is a junior synonym of P. peruviana

(Williamson et al. 2025).

C.

English Names: Following recommendations by Williamson et al. 2024 and

Williamson et al. 2025, use the English names Northern Giant Hummingbird (Patagona

peruviana) and Southern Giant Hummingbird (Patagona gigas).

Literature

Cited:

Areta, J.I., Halley, M.R., Kirwan, G.M., Norambuena, H.V., Krabbe, N.K.,

Piacentini, V.Q., 2024. The world’s largest hummingbird was described 131 years

ago. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 144.

https://doi.org/10.25226/bboc.v144i3.2024.a14

Boucard, A., 1893. Genera of Humming Birds. Pardy & Co.

Printers, London, UK.

Robinson,

B.W., Zucker, R.J., Witt, C.C., Valqui, T., Williamson, J.L., In Review. Songs

distinguish the cryptic giant hummingbird species and clarify range limits.

bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.06.30.662449

Schulenberg,

T.S., 2025. Splits, lumps and shuffles. Neotropical Birding 36, 66–69.

Vieillot,

L.P., 1824. La Galerie des Oiseaux. Constant-Chantpie, Paris, France.

Williamson,

J., Gyllenhaal, E.F., Bauernfeind, S.M., Bautista, E., Baumann, M.J., Gadek,

C.R., Marra, P.P., Ricote, N., Valqui, T., Bozinovic, F., Singh, N.D., Witt,

C.C., 2024. Extreme elevational migration spurred cryptic speciation in giant

hummingbirds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121, 1–11.

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2313599121

Williamson,

J.L., Gadek, C.R., Robinson, B.W., Bautista, E., Bauernfeind, S.M., Baumann,

M.J., Gyllenhaal, E.F., Marra, P.P., Ricote, N., Singh, N.D., Valqui, T., Witt,

C.C., 2025. Taxonomy, nomenclature, and identification of the giant

hummingbirds (Patagona spp.) (Aves: Trochilidae). Zoological Journal of

the Linnean Society 204, 1–16.

https://doi.org/doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaf036

Jessie L. Williamson,

Thomas Valqui, and Christopher C. Witt, July 2025

Vote tracking chart: https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCPropChart1044+.htm

Comments from Donsker (voting for

Bonaccorso):

“C. Should

Proposal 1059 pass I would support the English names proposed by the authors:

Patagona peruviana: Northern Giant Hummingbird

Patagona gigas: Southern

Giant Hummingbird”

Comments

from Stiles:

“YES to recognize 2 species: solid evidence from morphology voice,

distributions, and genetics.”

Comments

from Robbins:

“YES to the split. Genomic and vocal data make this a straightforward decision.

Also, YES to the nomenclatural part (B). Kudos to the authors for revealing

this cryptic taxon.”

Comments

from Remsen:

“YES to all three parts. This one was a

huge surprise to me and is a testimony to the value of careful fieldwork

combined with solid data on genetics and voice.

Unraveling this one is the kind of detective work that makes science

fun. Ted Parker would have loved this

for many reasons. Congratulations to the

research team.”

Comments from Zimmer: “YES

to all three parts – the vocal and genomic results make this one a slam-dunk in

what would otherwise be an extremely cryptic case if all we had to go on was

morphology. Congratulations to the

research team on some great sleuthing work.”

Comments

from Lane:

“YES to A, B, and C. This was a very cool mystery sleuthed out by the

Williamson et al team! I love this kind of discovery!

Comments

from Ottavio Janni: “I read the SACC proposal on the Giant

Hummingbird split, and although it seems like Northern GH and Southern GH will

win the day, I'm surprised no one suggested Chaski/Chasqui Hummingbird for the southern form.

“The Latin name Patagonia chaski

proposed for the northern form turns out to be a synonym of peruviana,

but it seemed to be an inspired choice, so it's a shame to lose it. It actually

makes more sense to me for the migratory southern form, and this would be an

opportunity to keep it, albeit in an English and not Latin name. P.

peruviana could then just stay Giant Hummingbird (and is the form that

occurs in the bulk of the range of the pre-split Giant Hummingbird).”

Comments

from Christopher J. Clark (guest voter): “I vote YES to split.

“I

have one substantive comment: the use of the world "song" to describe

the sound that differs between the species is misleading. Songs are typically thought of as a breeding-season,

male-limited behavior somehow associated with mating choices on the part of

females (although male-male competition over territories can be involved as

well). The suggestion that females and juveniles produce the

vocalization, and that they do so in sympatry (i.e. year round, not during the

breeding season) are indications that the vocalization is a call, not a song.

So, the true role of this sound in divergence and mating within these two

forms, and whether the vocalization might play a role in prezygotic mating

isolation, is unclear. That said, songs may vary because of song learning,

which evolves rapidly, while calls are thought to be innate and evolve much

more slowly. So, the fact that calls are

different between the forms supports the idea that ecological differences

between the forms have accumulated. I am convinced by the other differences

that these forms warrant species status. Finally, I trust that others have done

the careful taxonomy to confirm that P. peruviana is the appropriate

name for the new taxon.”

Comments

from Claramunt:

“A.

YES. Solid genomic evidence, and the new evidence on vocalizations solidifies

the phenotypic evidence.

“B.

YES. Glad that this was clarified quickly. The introduction of the new name chaski was unnecessary.”