Proposal (469) to South American Classification Committee

Species

limits in Paroaria

Effect on South

American CL: this proposal would elevate to

species rank various forms within Paroaria

that are currently treated as subspecies.

Background: Species limits in the genus Paroaria have always been somewhat arbitrary. Members of this genus are all adorned by red

somewhere on the face or throat, and variably developed crest from none to well

developed. The members differ in

distribution or lack of black on the face, bill coloration and upperparts

coloration (grayish to blackish). All

are whitish below. Here’s what our

current footnote states:

66. Paroaria gularis, P. baeri, and P. capitata

form a superspecies (Sibley & Monroe 1990); evidence for treating them as

separate species is weak (Paynter 1970a); Hellmayr (1938) suspected that P.

capitata might best be treated as a subspecies of P. gularis,

and Meyer de Schauensee (1966) suspected that baeri might also

best be treated as a subspecies of P. gularis. The subspecies P. g. nigrogenis of Venezuela was formerly (e.g., REF)

treated as a separate species from Paroaria gularis. Dávalos & Porzecanski (2009) also found

evidence that nigrogenis was not most

closely to P. gularis; they elevated

all diagnosable taxa to species rank based on the phylogenetic species concept.

New information: Dávalos and

Porzecanski (2009) published a paper based on molecular as well as a

morphological analysis of the genus. They examined over 600 specimens measured

and scored them for plumage characters.

Molecular data included complete sequences of cytochrome b. Note that they did not have molecular data

for xinguensis.

They characterized species based on

morphological data, in particular whether characters shared by individuals were

of a unique combination and restricted to a geographic region. When these unique characters were fixed in

all individuals sampled, the population was considered diagnosably distinct and

a hypothesized phylogenetic species. The

molecular data was then looked at with at least two individuals per

hypothesized phylogenetic species looking for unique fixed mutations for

support of these as valid species.

They suggest separating the genus into

8 species based on these data:

coronata - 24

unique substitutions in the cytochrome b gene

dominicana - 33 unique substitutions in the cytochrome b gene

nigrogenis - 20 unique

substitutions in the cytochrome b gene

xinguensis – no

molecular data.

baeri - 11

unique substitutions in the cytochrome b gene, but since sequences of

its sister xinguensis, are lacking, this may be an overestimate.

gularis - two unique substitutions in the cytochrome b gene

cervicalis - two unique substitutions in the cytochrome b gene

capitata - five

unique substitutions in the cytochrome b gene

They stated the following: “Lumping of nigrogenis, cervicalis

and gularis is not supported by

genetic or morphological data.” This is perhaps the most clear-cut result in

this study. The taxon nigrogenis does not appear to be closely

related to gularis; it is well

differentiated based on the molecular data, and well differentiated based on

the morphological data. Note also that

Restall et al. (2006) separated nigrogenis

from gularis and note that the two

are sympatric in extreme SW Venezuela with no evidence of hybridization. These data strongly suggest that nigrogenis is a valid biological

species.

The relationship of capitata,

cervicalis, and gularis is more problematic. All share a similar color pattern with

red head, black throat and breast. The

species capitata has an entirely

yellow bill, unlike cervicalis and gularis.

The form cervicalis has no

black around the eyes, whereas gularis

does have a small dark area around the eyes; this is essentially the main

difference between the two and does not seem to be all that impressive to

me. Vocal data would be good to have to

compare. Furthermore, the type of cervicalis is apparently aberrant,

further muddying this situation. The

apparent fixed genetic differences are of interest, although only two cervicalis were sampled, a larger sample

size would have been better. The range

of cervicalis and gularis likely meet somewhere in W

Brazil or NE Bolivia and sympatry should be looked for, and any evidence of

hybridization. The plot of ML distances

showed the gularis-cervicalis comparison to be intermediate

between within-species variation and between-species variation, in other words

more grey than black or white. At this

point it does not seem clear to me that cervicalis

warrants separation as a biological species.

On the other hand, capitata is

geographically isolated from cervicalis-gularis and shows a greater degree of

differentiation morphologically and molecularly. Retaining it as separate seems

reasonable.

Similarly, the division of xinguensis from baeri is

weak. No molecular data were available for xinguensis

to begin with. The form is diagnosable in that it has a black throat instead of

the red throat of baeri, yet only 5

specimens in total for both of these taxa were studied. It seems very premature

to separate xinguensis from baeri at this point.

I think that it is best to separate the

issues into two parts:

A. Elevate nigrogenis to species rank.

Masked Cardinal (used in Restall et al 2006) is an appropriate English

name given that it is the only one with a bold black stripe through the face in

this genus of “cardinals.”

B. Also elevate the following to

species rank: cervicalis and xinguensis.

Recommendation:

I recommend a YES on A and a NO on

B. Dávalos and Porzecanski regard all

diagnosable units as species, using PSC, so there is really no evidence for any

of the other diagnosable taxa being ranked as species under BSC.

Literature Cited.

Dávalos, L.M., Porzecanski, A.L. (2009)

Accounting for molecular stochasticity in systematic revisions: species limits

and phylogeny of Paroaria. Molecular

Phylogenetics and Evolution 53:

234-248.

RESTALL, R.,

C. RODNER, AND M. LENTINO. 2006. Birds of northern South America. An

identification guide. Christopher Helm, London.

Alvaro Jaramillo, October 2010

=========================================================

Comments from Stiles: A.

YES – both gularis and nigrogenis also occur in NE Colombia at

no great distance from one another; although I am not aware of any locality

where both have been taken here, I can also detect no indication of

intermediacy in any of the specimens here. B. NO – I agree with Alvaro that

evidence for splitting these two is at present inconclusive.”

Comments from Nores: “A.

YES. Aunque por distribución parece corresponder a una subespecie, los

datos moleculares y el análisis hecho en la propuesta por Álvaro indican que se

trata de una especie. B. NO. Coincido con Álvaro que no hay

evidencias concluyentes como para elevar estas subespecies al rango de especies.”

Comments from Robbins: “A. YES.

Both molecular and morphological data support this conclusion. B. NO, until additional data are presented

supporting elevating these to species status.”

Comments from Remsen: A. YES.

But only because of Restall et al.’s report of sympatry, of which I was

not aware, and Gary’s report of near parapatry.

Otherwise, I see no evidence in this paper, either morphological or

genetic, that supports species rank for nigrogenis. That nigrogularis

does not group with gularis might be

a simple gene tree vs. species tree problem, given that only one mtDNA was

sequenced. B. NO. The authors of the paper have documented that

there are 8 diagnosable taxa based on plumage.

Whether those diagnosable units are ranked as valid subspecies or PSC

species is a matter of taste - - the results are still the same. Any use of comparative genetic distances for

a single locus for assigning taxon rank is naïve. That there are fixed genetic differences in

cyt b among taxa known to also have diagnosable, presumably genetically based

plumage differences is of interest but how that relates to taxon rank is a

mystery to me. If there were no fixed

differences in cyt b, but fixed plumage differences, would the authors have

arrived at a separate taxonomic decision?”

Comments from Zimmer: “A. YES, based on reports of sympatry and parapatry with gularis, coupled with diagnosable plumage differences that are on a scale with some of the differences between currently recognized species in the genus. B. NO. I see nothing in the paper by Dávalos and Porzecanski to indicate that cervicalis and xinguensis are anything more than diagnosable subspecies/phylogenetic species, which is how we currently treat them.”

Comments from Pacheco: “A.

Yes. A julgar pela aparente

ausência de espécimes intermediários entre os táxons nigrogenis e gularis, no sw.

Venezuela e, possivelmente, no nw Colômbia – sou favorável ao status de espécie

para nigrogenis sob o BSC. B. No. Em vista das informações disponíveis é

prematuro considerar cervicalis e, sobretudo, xinguensis como

espécies plenas sob o BSC.”

Comments

from Perez: “Paroaria

gularis and nigrogenis

are largely divergent in both molecular and morphological characters; however,

the key data supporting species rank was the following information:

“Note

also that Restall et al. (2006) separated nigrogenis from gularis

and note that the two are sympatric in extreme SW Venezuela with no evidence of

hybridization. These data strongly suggest that nigrogenis is a

valid biological species.”

“Although Gary commented on another

potential zone of potential parapatry without records of intermediate

specimens, the SW Venezuelan zone of sympatry was the key issue.

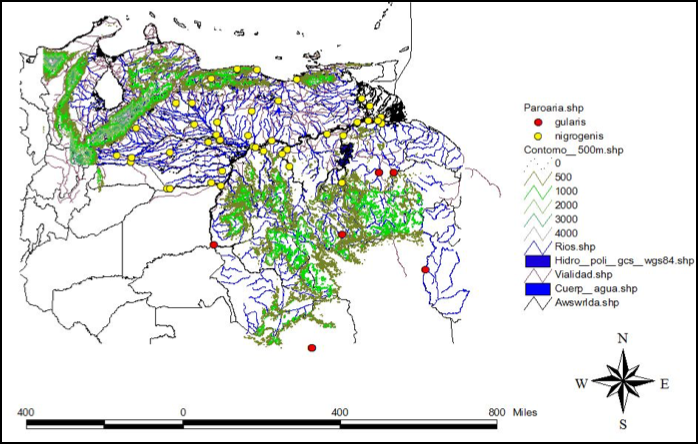

“Following this decision, I was

interested in doing a more in-depth research in the area to describe this zone

of sympatry or find a potential area for a contact zone study between both gularis and nigrogenis. Together with Miguel Lentino, from the Colección

Ornitológica Phelps (COP), we produced a map (see below) including all records

of these species present in three of the most important ornithological

collections in Venezuela (with specimens from SW Venezuela). To our surprise,

we did not find any confirmation of sympatry; in fact, the closest records

between both taxa were about 200 km from each other. We also requested

information for many birdwatchers, who routinely travel around the area, and

found no evidence for such claimed sympatry. We did find, however, two

misidentified COP specimens collected at El Dorado, at SW Venezuela. Those

specimens were labeled as nigrogenis

whereas the rest of specimens in the same locality were gularis, potentially misleading description of biogeographic patterns.

The question now is if we will keep our decision to elevate nigrogenis to species rank, based only

on the potential parapatry in Colombia, and the large morphological (even in

juveniles) and molecular differentiation between gularis and nigrogenis. At

least, I think we need to discuss if such differences are enough to claim

reproductive isolation under the biological species concept we use here (which

I think will be difficult); if not, we might need to reconsider our decision.”

New Comment from Remsen: “Jorge’s comments

and research leads me to change my vote to NO.

The primary reason I voted for this was the alleged sympatry (and given

what I perceive as limited meaningful differences among these parapatric taxa,

I was always suspicious).”