Proposal (534) to South American

Classification Committee

Changes

to Pipridae genera and sequence

A. Changes to generic allocation

Background: The phylogeny of the manakins has been

investigated substantially over the last 20 years or so, and the arrangement we

follow does not completely correspond to the results of either morphological or

molecular studies done on the family.

Recent molecular studies suggest that we need to make at least some

changes in the allocation of species to genera.

Based on

syringeal morphology, Prum (1992) concluded that the large manakin genus Pipra was polyphyletic and split the

small manakins of the serena group

out into the genus Lepidothrix, and

recognized Dixiphia for the

White-crowned Manakin, P. pipra. The recognition of Lepidothrix has been accepted by nearly all subsequent authors and

was part of the original base taxonomy for SACC based on the treatment in

Dickinson (2003). Dixiphia has not been accepted by SACC including a recent proposal

that considered both Prum’s syringeal data and molecular data from Rego et al

(2007). Since that time, two additional

molecular studies (Tello et al 2009) and McKay et al (2010) provide additional

data regarding relationships in Pipridae.

New information: Since 2007,

three studies using DNA sequences have provided data and analysis that bears on

this issue. Rego et al (2007) used

mitochondrial cytochrome B and rRNA 16S to examine relationships within the

Pipridae. They sampled 18 species

representing 13 genera. McKay et al.

(2010) used two mitochondrial genes (nd2 and col) and a nuclear intron Musk

intro 3 to look at Pipridae, sampling 14 species representing 14 genera. Tello et al. (2009) used two nuclear genes

(RAG-1 and RAG-2) to look at the broader radiation (Tyrannides) from Tyrannidae

though Cotingidae to Pipridae. They sampled a total of 19 manakin species

including representatives of all of the relevant genera.

The relevant

portions of the trees for Pipridae from all three molecular studies are

reproduced below. One thing you will

note is that the taxon sampling is not close to complete in any of these

studies, but that there is a fair amount of complementarity among the taxa used

in the studies. There are a number of

things going on, and certainly not complete agreement among the studies. All three studies identify a clade of what I

would call classic manakins (plus the weird Heterocercus),

including the genera Pipra, “Dixiphia”,

Heterocercus, Manacus, Lepidothrix, and Machaeropterus. There is some disagreement on the

relationships among these genera.

However, one subclade is consistently returned by all 3 studies. That clade contains Machaeropterus, Pipra (or

Dixiphia) pipra, and the cornuta species

group of Pipra (represented by rubrocapilla, erythrocephala and/or mentalis in the three studies). The remaining species of Pipra (the aureola species group) do not cluster with these taxa in the Rego

et al (2007) or the Tello et al (2009) studies.

Unfortunately, McKay et al. (2010) lacked a representative of the aureola group.

The clade with Machaeropterus, Pipra pipra and the cornuta

group does not have a consistent topology in the 3 studies. Rego et al. (2007) have Machaeropterus interposed between Pipra pipra and the cornuta

group, whereas the other two studies have Machaeropterus

at the base of the clade.

It

appears from these studies that the genus Pipra

even with the removal of Lepidothrix and

“Dixiphia” pipra is not monophyletic.

The generic name Pipra belongs

with the aureola group. That group seems to form straightforward

clade. There are 3 generic names associated with the clade that includes the cornuta group currently placed in Pipra.

Dixiphia is the oldest name,

and P. pipra is the type. Machaeropterus

applies to those species currently in that genus and Ceratopipra would be the appropriate name for the cornuta group.

There

would seem to be 3 possible treatments for the Dixiphia, Machaeropterus, and Ceratopipra

clade. A) The taxa could all be placed

in the genus Dixiphia, the oldest

name for the group. B) The three names

available could all be used, recognizing Machaeropterus

as currently defined, Dixiphia as

monotypic, consisting of just pipra,

and Ceratopipra for the cornuta group. C) Retain Machaeropterus

and place pipra and the cornuta group in Dixiphia. The first two

treatments are consistent with all three molecular studies. The third, however, conflicts with the tree

of Rego et al. Thus, I think the two

appropriate options are using Dixiphia for

all these taxa or the 3-genera treatment.

Because Machaeropterus stands

out morphologically, in plumage pattern and behavior from the other species, I

am disinclined to place all species in Dixiphia.

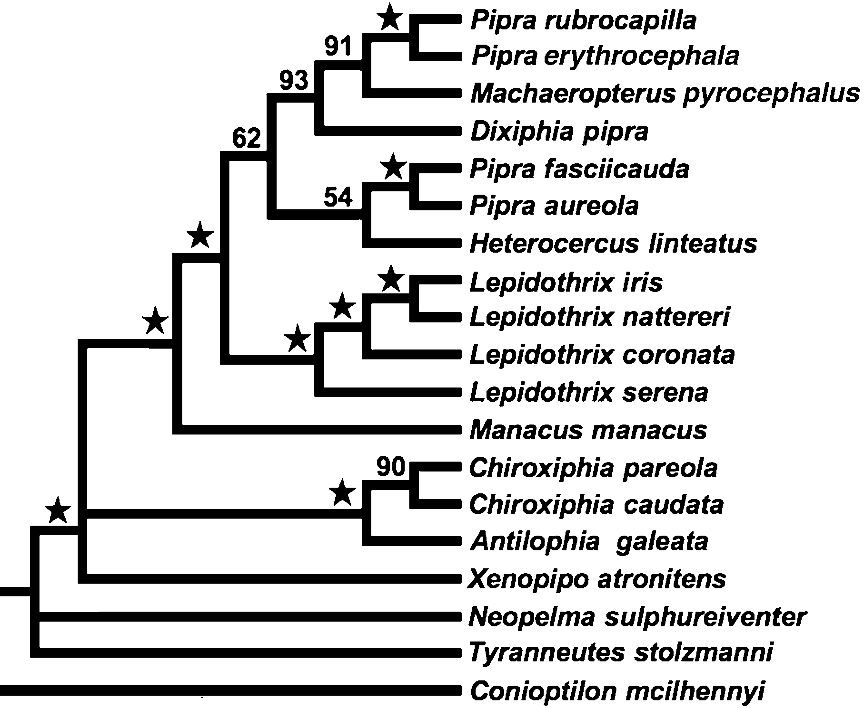

Rego et al. (2007) tree:

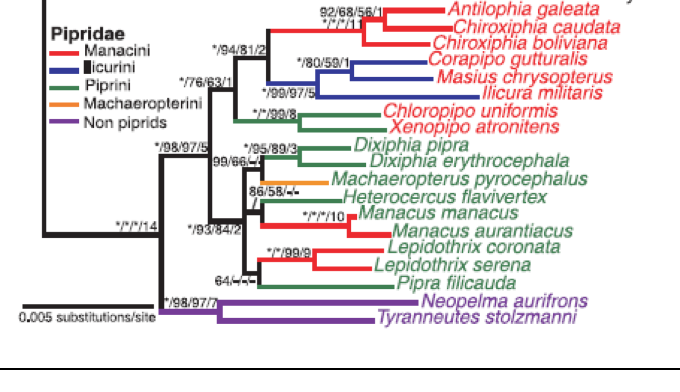

Tree from Tello et al (2009):

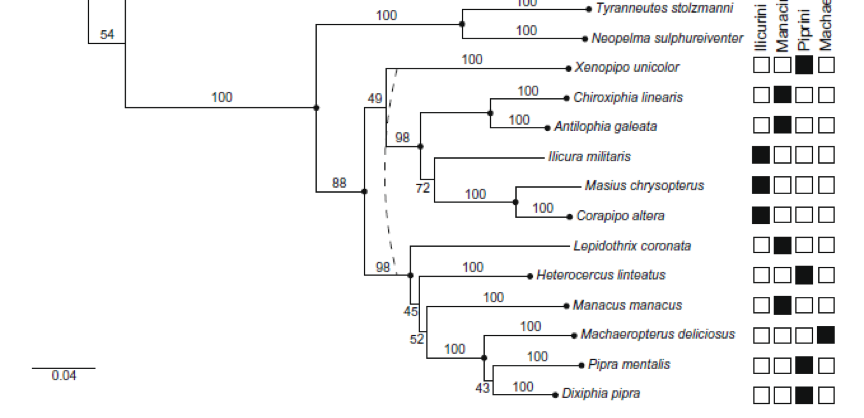

Tree from McKay et al (2010):

Recommendation:

The

molecular data clearly indicate that Pipra

as currently constituted is not monophyletic.

So I recommend removing Pipra

pipra, cornuta, chloromeros, rubrocapilla, and erythrocephala from Pipra. Two possible treatments for the clade found in

all three studies including these species plus the genus Machaeropterus are possible:

A) All taxa placed in the genus Dixiphia,

the oldest name for the group. B) The

three names available could all be used, recognizing Machaeropterus as currently defined, Dixiphia as monotypic, consisting of just pipra, and Ceratopipra for

the cornuta group. Because Machaeropterus

stands out morphologically, in plumage pattern and behavior from the other

species, I am disinclined to place all species in Dixiphia, and recommend choice B.

B. Sequence of genera in Pipridae

Assuming that

SACC splits Pipra, and basically

accepts the results of these molecular studies, we need to adjust the order of

genera in Pipridae to reflect the results from these molecular studies. All 3 studies have Tyranneutes and Neopelma

basal. They also identify two clades,

one consisting of Ilicura, Masius,

Corapipo, Antilophia, Chiroxiphia, and Xenopipo. The other clade contains the remaining

genera: Pipra, Lepidothrix, Manacus,

Heterocercus and Dixiphia (sensu

lato). The topology of the first clade

seems well-established. Xenopipo is basal, Antilophia and Chiroxiphia

are sisters, Masius and Corapipo are sisters, and Ilicura is sister to them.

The other clade

has much more variation across the 3 studies, and bootstrap values for much of

the structure are poor. However, as

noted in part A, a clade containing Machaeropterus,

Dixiphia, and Ceratopipra is returned by all three studies, and a sequence of

those taxa with Dixiphia between the

other two is consistent with all of the topologies. The remaining genera, Pipra, Lepidothrix, Manacus, and

Heterocercus, have very different arrangements in the three studies. A sequence of Manacus, Heterocercus, Pipra, and Lepidothrix seems like it would best reflect the potential

relationships suggested in these studies.

So I recommend

we place the genera of Pipridae in the following sequence, which is consistent

with the molecular topologies and maintains the current sequences as much as

possible:

Neopelma

Tyranneutes

Ilicura

Masius

Corapipo

Antilophia

Chiroxiphia

Xenopipo

Machaeropterus

Dixiphia

Ceratopipra

Manacus

Heterocercus

Pipra

Lepidothrix

References:

Dickinson,

E. C. (ed.). 2003. The Howard and Moore complete checklist of

the birds of the World, Revised and enlarged 3rd Edition. Christopher Helm,

London, 1040 pp.

McKay, B. D., F. K. Barker, H. L.

Mays, Jr., S. M. Doucet, and G. E. Hill.

2010. A molecular phylogenetic

hypothesis for the manakins (Aves: Pipridae). Molecular Phylogenetics and

Evolution 55:733-737.

Prum, R. O. 1992. Syringeal morphology, phylogeny, and

evolution of the Neotropical manakins (Aves: Pipridae). American Museum Novitates 3043.

Rego, P. S., J. Araripe, M. L. V.

Marceliano, I. Sampaio, and H. Schneider.

2007. Phylogenetic analyses of

the genera Pipra, Lepidothrix and Dixiphia (Pipridae, Passeriformes) using partial cytochrome b and

16S mtDNA genes. Zoologica Scripta

2007:1-11.

Tello, J. G., R. G. Moyle, D. J.

Marchese, and J. Cracraft. 2009. Phylogeny and phylogenetic classification of

tyrant-flycatchers, cotingas, manakins and their allies (Aves: Tyrannides). Cladistics 25:429-465.

Doug Stotz, July 2012

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Comments from Zimmer:

“A. YES. I would concur with

Doug’s rationale for choice “B”: That

is, to retain Machaeropterus as

currently defined, restrict Dixiphia

to pipra (which is more than one

species anyway), and move the cornuta group

(including chloromeros, in addition

to the species sampled) to Ceratopipra. Given the distinctiveness of Machaeropterus, I just can’t see lumping

everything into Dixiphia. B. YES

to Doug’s proposed sequence, which makes the most sense while minimizing

upheaval.”

Comments

from Stiles: “A. YES to B, especially as

the display behavior of pipra is

really quite different from that of at least erythrocephala and mentalis

and setting it apart also fits Prum’s morphological data.”

Comments from Pacheco: “A. Yes. B. YES. A sequência me parece

consistente com os dados recentes disponíveis, incluindo uma proximidade na

sequência entre Dixiphia e Machaeropterus.”

Comments from

Stiles: “YES,

including the recognition of three genera: Ceratopipra,

Dixiphia and Machaeropterus.”

Comments from Pérez-Emán: “A: YES. Data are consistent with recognition of

Dixiphia, Machaeropterus, and Ceratopipra.

B: YES. Sequence is consistent with what

we know so far about these taxa, while creating the fewest changes.”

Comments from Jaramillo: “YES - for both A and B. The final arrangement

makes sense and is based on various solid data.”

Comments from Nores: “Changes to generic allocation. YES, choice B. The

resurrection of the genus Ceratopipra is consistent with the Rego et

al. study, but conflicts with the trees of Tello et al. and the McKay et al.

Note, however, that this does not mean eliminating

the genus Machaeropterus,

which groups a set of species quite similar in color

to each other and different from the rest.

Sequence of genera in Pipridae. NO. Following the criteria of the taxon that splits first

(presenting the lesser number of ancestors, that is, internal nodes) being

placed at the top of the sequence and so on, we obtain the following sequences

of the trees of Rego et al., Tello et al. McKay et al. and a new sequence.

SACC Stotz Rego et al. Tello et al. McKay et al.

Neopelma Neopelma Neopelma Neopelma Neopelma

Tyranneutes Tyranneutes Tyranneutes Tyranneutes Tyranneutes

Ilicura Ilicura Xenopipo Xenopipo Lepidothrix

Masius Masius Antilophia Antilophia Heterocercus

Corapipo Corapipo Chiroxiphia Chiroxiphia Manacus

Machaeropterus

Antilophia Manacus Ilicura Machaeropterus

Lepidothrix Chiroxiphia Lepidothrix Corapipo Dixiphia

Manacus Xenopipo Heterocercus Masius Ceratopipra

Antilophia

Machaeropterus Pipra Heterocercus Xenopipo

Chiroxiphia Dixiphia Dixiphia Manacus Antilophia

Xenopipo Ceratopipra Machaeropterus Lepidothrix Chiroxiphia

Heterocercus Manacus Ceratopipra Machaeropterus Ilicura

Pipra Heterocercus

Dixiphia Corapipo

Pipra

Ceratopipra Masius

Lepidothrix

Proposed new sequence:

Neopelma

Tyranneutes

Xenopipo

Antilophia

Chiroxiphia

Ilicura

Corapipo

Masius

Manacus

Heterocercus

Pipra

Lepidothrix

Machaeropterus

Dixiphia

Ceratopipra