Proposal (555) to South

American Classification Committee

Reclassification

of the Scolopacidae

Effect

on SACC: This proposal would divide our current family

Scolopacidae into 5 subfamilies and change the sequence of genera within the

family.

Background:

Our current classification does not include subfamily structure and

follows a traditional sequence of genera.

The reason for the lack of subfamily structure was our wise assessment

of the lack of concordance among other classifications and the absence of a

solid DNA-based phylogeny. Our footnote

is as follows:

1. <note on genera, linear sequence> Jehl (1968b). The

family Scolopacidae is traditionally split into five or more subfamilies and

additional tribes (e.g., AOU 1998). Livezey (2010) recognized four

subfamilies (Arenariinae, Calidrinae, Tringinae, Scolopacinae) and maintained

the phalaropes as a separate family. Genetic data

(e.g. Gibson & Baker 2012), however, provide very weak or no support for

the monophyly of these groups, and although the phalaropes are monophyletic,

they are deeply embedded in the Scolopacidae and sister to the tringines. Gibson & Baker (2012) identified five

major lineages in the family. SACC proposal needed to recognize five subfamilies.

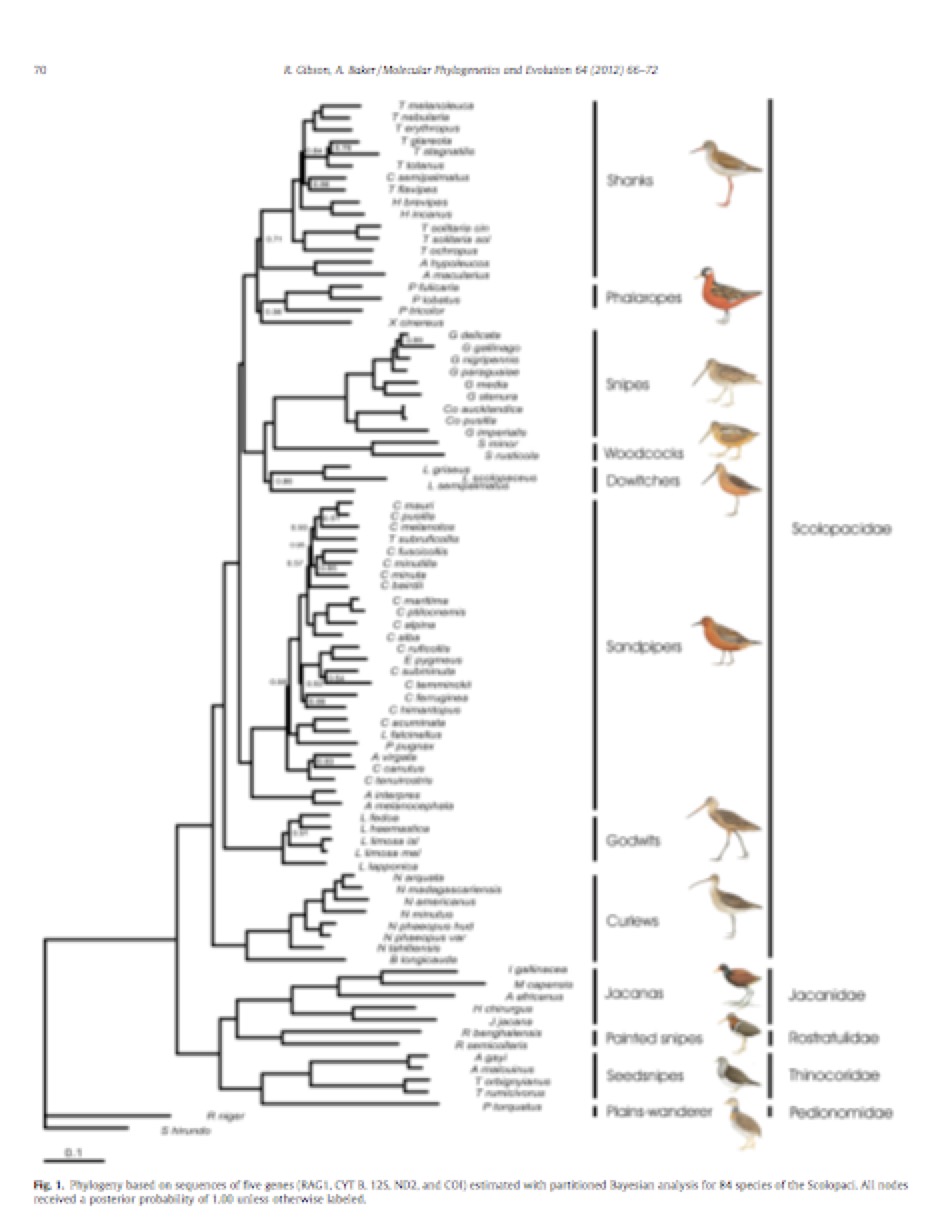

New information: Gibson & Baker (2012) produced a

phylogenetic hypothesis based on strong taxon-sampling (84 species) and good

gene-sampling (6300+ bps; 1 nuclear + 4 mitochondrial genes). Branching patterns in general were well-resolved

(except for problems within the explosive calidridine radiation). Here is their tree – sorry about the poor

resolution – if anyone needs a pdf, just let me know:

I

suggest that the best interpretation of the tree is to recognize 5 major

lineages and to give each one subfamily rank.

Note that Gibson & Baker name 8 groups, not 5, which would be an

alternative treatment, i.e. 8 subfamilies.

I suggest condensation to five for the following reasons.

(1) The

Snipe-Dowitcher-Woodcock group is probably best treated as a single group

because the branch lengths connecting them are very short, inclusion of Limnodromus semipalmatus in the

Dowitchers has weak support, and taxon-sampling within the Woodcock and Snipe

groups is weak (including absence of Limnocryptes).

(2) The

Phalaropes if treated as a subfamily would technically also have to include Xenus (Terek Sandpiper), which groups

with them albeit with substandard support.

That result is best treated as anomalous, in my opinion, until

corroborated by additional data (parallel to the initial anomalous results for Pluvialis; see Baker et al. 2012). An alternative approach would be to recognize

the Phalaropes as a subfamily and to retain Xenus

in its traditional spot in the Tringinae or place it as Incertae Sedis. Although not giving the phalaropes subfamily

rank might seem extreme, keep in mind that Phalaropus

tricolor (which really deserves to have its monotypic genus status

reinstated: Steganopus) strikes many

field people as having some tringine-like behaviors.

Tangentially,

I take the opportunity to point out that Livezey (2010) placed the phalaropes

in their own family, as they were for most of their history due to their

unusual morphology. Assuming that the

gene-based phylogeny reflects historical relationships, this is yet another

warning for use of morphological data to infer phylogeny. Livezey’s careful and quantitative analysis

of hundreds of phenotypic characters was unable to distinguish highly derived

morphological change from lineage history, just as it was unable to identify

strongly convergent morphology (e.g., Livezey’s sister relationship between

Podicipedidae and Gaviidae).

Another

point worth considering is giving subfamily rank to the Turnstones. Although not labeled as a group by Gibson

& Baker, just looking at relative divergence, they deserve naming if

Woodcocks, Snipes, and Dowitchers do, and their distinctive morphology has led

to their classification as a separate family or subfamily in the past. But looking at branch lengths and node depths

in the tree, if turnstones are treated as a subfamily, then snipes, woodcocks,

and dowitchers also should be. As

predicted from any categorical scheme inflicted on a continuum of

differentiation, borderline situations are inevitable. I suggest that that if we decide to include

the Tribe level in our classification, then turnstones would be a prime

candidate for recognition at that level.

Taking

the Gibson-Baker tree and transforming it to a classification for species in

the SACC area, including changes in species sequence to match the tree, would

look like this:

SCOLOPACIDAE

(SANDPIPERS)

Numeniinae

Bartramia longicauda Upland Sandpiper

Numenius borealis Eskimo Curlew

Numenius phaeopus Whimbrel

Numenius americanus Long-billed Curlew

Limosinae

Limosa

lapponica Bar-tailed Godwit

Limosa limosa Black-tailed Godwit

Limosa haemastica Hudsonian Godwit

Limosa fedoa Marbled Godwit

Arenariinae

Arenaria

interpres Ruddy Turnstone

Arenaria melanocephala Black Turnstone

Aphriza virgata Surfbird

Calidris canutus Red Knot

Calidris alba Sanderling

Calidris pusilla Semipalmated Sandpiper

Calidris mauri Western Sandpiper

Calidris minutilla Least Sandpiper

Calidris fuscicollis White-rumped Sandpiper

Calidris bairdii Baird's Sandpiper

Calidris melanotos Pectoral Sandpiper

Calidris alpina Dunlin

Calidris ferruginea Curlew Sandpiper

Calidris himantopus Stilt Sandpiper

Tryngites subruficollis Buff-breasted

Sandpiper

Philomachus pugnax Ruff

Scolopacinae

Limnodromus

griseus Short-billed Dowitcher

Limnodromus scolopaceus Long-billed

Dowitcher

Gallinago imperialis Imperial Snipe

Gallinago jamesoni Andean Snipe

Gallinago stricklandii Fuegian Snipe

Gallinago nobilis Noble Snipe

Gallinago undulata Giant Snipe

Gallinago delicata Wilson's Snipe

Gallinago paraguaiae South American Snipe

Gallinago andina Puna Snipe

Tringinae

Phalaropus

tricolor Wilson's Phalarope

Phalaropus lobatus Red-necked Phalarope

Phalaropus fulicarius Red Phalarope

Xenus cinereus Terek Sandpiper

Actitis macularius Spotted Sandpiper

Tringa solitaria Solitary Sandpiper

Tringa incana Wandering Tattler

Tringa melanoleuca Greater Yellowlegs

Tringa semipalmata Willet

Tringa flavipes Lesser Yellowlegs

Tringa glareola Wood Sandpiper

Additional

points:

1. The

above does not deal with the problems of generic limits in the Calidrinae,

e.g., sister relationship of Aphriza

to C. canutus; see Banks (2012). Dick Banks is submitting a proposal to NACC

on this, and I suggest we do not meddle until dust settled.

2. The

sequence from Xenus through T. glareola now conforms to current NACC

sequence.

3. SACC

proposal 548

would split Chubbia from Gallinago, but that would not change the

linear sequence of species.

4. Banks (2012) used Arenariinae Stejneger, 1885, as the

subfamily name, even though Calidrinae Reichenbach, 1849, is older name: “The

family-group name for the turnstones was originally based on the generic name Strepsilas

Illiger, 1811 by Gray (1840), as Strepsilinae (fide Bock 1994:138). Stejneger

(1885:95) introduced the name Arenariinae, based on Arenarius Brisson,

1760, a name with many years priority over Strepsilas, and it thus

became the proper name for the subfamily (see Ridgway 1919:42). For purposes of

priority, Arenariinae dates from 1840 (ICZN 1999, Art. 40.2). The name

Calidridinae was not established until l849 (fide Bock 1994:138) and thus is a

junior synonym of Arenariinae.”

Discussion

& Recommendation: See proposal 552 for my views on the value of using

additional ranks, in this case subfamily, in our classification. I am open to alternative classifications, but

barring viable alternatives, I recommend a YES on this as improving the

information content of our classification.

Literature:

BANKS, R. C.

2012. Classification and nomenclature of the sandpipers (Aves:

Arenariinae). Zootaxa 3513: 86-88.

GIBSON, R.,

AND A. BAKER. 2012. Multiple

gene sequences resolve phylogenetic relationships in the shorebird suborder Scolopaci (Aves: Charadriiformes). Molecular

Phylogenetics and Evolution 64: 66–72.

LIVEZEY, B.

C. 2010.

Phylogenetics of modern shorebirds

(Charadriiformes) based on phenotypic evidence: analysis and

discussion. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 160: 567-618.

Van Remsen, October 2012

Comments from Stiles: “A very qualified YES (but note that Chubbia is not reinstated here but will be if 546 passes. Also see

the extensive Raty commentaries on the Scolopacidae in the “TiF Classification”

(whatever this is). Note that here Calidris

is restricted to canutus and a

couple of OW species, and includes Aphriza;

all the smaller Calidris are treated

in Ereunetes. Also, Limicoli is considered to have priority

over Scolopaci (or -inae, for subfamilies).

These points seem worth considering.”

Comments from Pacheco: “YES. Considerando todos os pontos, incluindo os adicionais.”

Comments

from Cadena: “YES (see comments under proposal 552).”

Comments

from Pérez-Emán: “NO. I

like this proposal better than previous ones on the same topic (552 and 553) because

it incorporates some behavioral and morphological issues into the discussion

(in the case of Phalaropes and Turnstones). However, integrating such

information provides an interesting example about how different interpretations

of the same data might result in a different subfamily classification

(discussions in Gibson & Baker (2012) and in this proposal). Moreover, as

pointed out by Remsen, depending on the importance or interpretation given to

branch lengths or node depths in the tree, one can come out with different

subfamily arrangements. Thus, such borderline situations discussed by Remsen

could be more the rule than the exception and might result in non-meaningful

classifications at the subfamily level.”

Comments

from Nores: “YES. This seems

like the best way to go given available evidence.”

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“NO. I realize the subjectivity of this

enterprise, and that Terek Sandpiper is making things difficult here. But the

Gibson Baker paper is but one set of data, and one could find a lot of

morphological, behavioral and other details that clarify that Terek (Xenus) is a Tringine. I think this is

clearly a spurious result here in the genetic data and I do not think we should

really consider this likely, unless some other new and compelling information

came up to put Xenus in with the

phalaropes. My vote would be to recognize the Phalaropes as a subfamily, and

make the decision to leave Xenus out

of that and put it in the Tringines. But subfamily distinctions should of

course tell us about major subdivisions in a family, but these subdivisions

should be informative, to add some structure and logic to the organization

within the family. It is much more structured and logical as well as

informative to have the Phalaropes under their own subfamily!

“Similarly, I

would give the dowitchers their own subfamily. Snipe and woodcock are a good

group; the division between them is relatively deep, but not as deep as between

them and the dowitchers. The dowitchers are very different from snipe and

woodcocks, and maintaining them as separate adds to a more informative and

structured understanding of this family. Other than long bills which ally them

to the snipe/woodcocks, in terms of coloration, vocalizations, migration and

behavior they converge with some Arenariines (sandpipers) and Limosinines

(godwits). They are distinctly different from woodcocks and snipe.

“I know, where

do you draw the line then? Well, I would keep turnstones in with the rest of

the sandpipers. I draw the line there. They are distinctive in many ways, but

fit well within that relatively diverse group. …. although I could be swayed on

this point.”

Comments

from Zimmer: YES. This

seems to be the most sensible arrangement to me, given the current molecular

data. As for the Phalarope question (separate subfamily or not?), I

heartily concur with Van’s statement that P.

tricolor is as much tringine as phalarope with regards to foraging behavior

and foot morphology.”