Proposal (561) to South American

Classification Committee

Transfer Milvago

chimango to Phalcoboenus

Effect

on SACC list:

If this proposal passes, Milvago chimango would become Phalcoboenus

chimango.

Background: Milvago chimango traditionally has

been treated in Milvago, and I am unaware of any doubts concerning its

placement there. In fact, Brown &

Amadon (1968) treated them as forming a superspecies, but this is clearly an

error because they overlap fairly extensively in their distribution (in

Paraguay, Uruguay, extreme S Brazil). Vuilleumier

(1970) questioned their close relationship because of differences in shape and

ecology, but he retained chimango in Milvago.

New

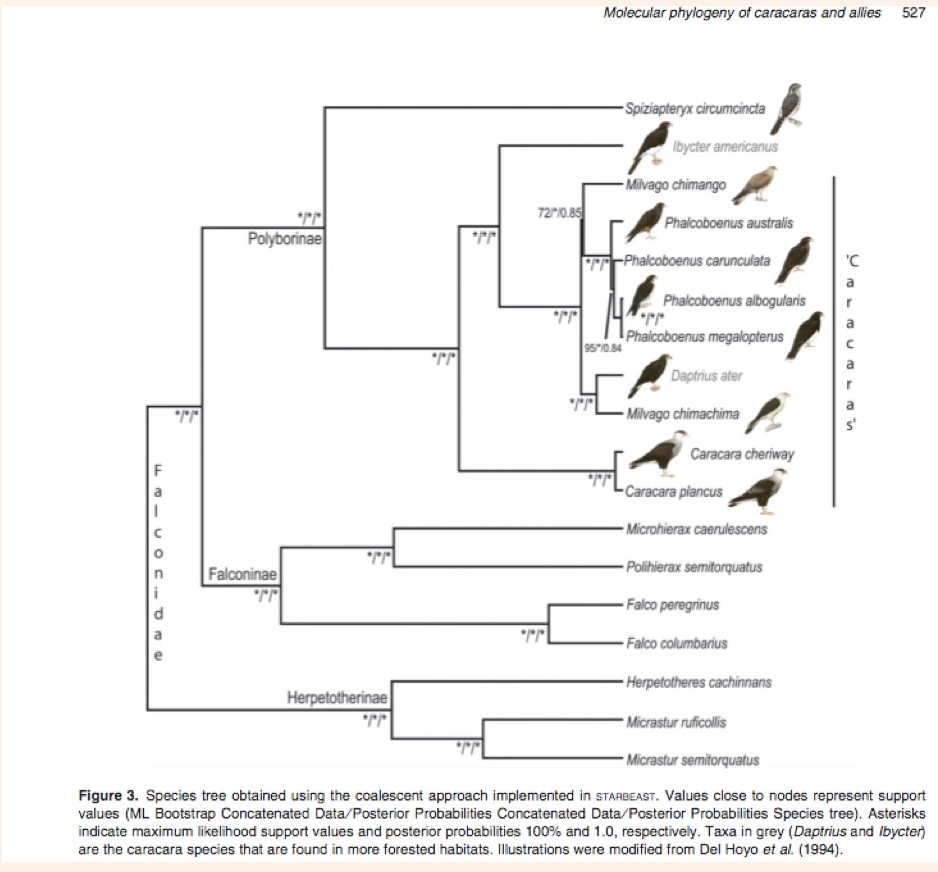

information: Fuchs et al. (2012) sampled all of the

caracaras using DNA sequence data from mtDNA (2308 bp) an nDNA (5008 bp). Milvago chimango was not the sister

taxon to M. chimachima in either the mtDNA or nDNA analyses, but was the

sister to Phalcoboenus with weak or no support. However, in the concatenated dataset, support

for that relationship was much stronger.

In all analyses, Daptrius ater was sister to M. chimachima. Clearly, Milvago as traditionally

defined is not monophyletic. Here is

their species tree:

Fuchs

et al. (2012) considered 4 taxonomic options:

1. One genus: Merge all species from Milvago

and Phalcoboenus into Daptrius (which has priority).

2. Two genera: Move Milvago chimachima

into Daptrius and Milvago chimango into Phalcoboenus.

3. Three genera: Move chimango into Phalcoboenus.

4. Four genera: Retain traditional generic

boundaries and describe a new genus for chimango.

They

recommended Option 3 (= 3 genera; Milvago chimango becomes Phalcoboenus

chimango) because “it maintains monophyletic genera while recognizing

differences in overall shape, diet and habitat use between and M. chimachima

and D. ater.”

Recommendation: I have no recommendation on this one, and

have written the proposal to follow the recommendation of Fuchs et al. Their option 4 is clearly out in the absence

of a genus for chimango, but otherwise I have no opinion on the other

three. Although I once knew D. ater

and M. chimachima very well, I don’t know the rest well enough to

contribute to the subjective evaluation, and will listen to what others have to

say. Strictly on plumage and general

shape, Daptrius and Phalcoboenus are fairly similar, and Daptrius

ater is certainly more similar to them in general behavior and ecology than

it is to its former congener (now Ibycter americanus) and obviously more

similar in plumage to Phalcoboenus than it is to Milvago chimachima

(thus I would rank Option 2 fairly unpalatable). So, pending input from more knowledgeable

people, I think Option 1 (Milvago and Phalcoboenus into Daptrius)

is viable – these are all generalists of open country with roughly similar

size, proportions, and behavior.

A

YES vote would endorse the solution proposed by Fuchs et al. (2012), Option 3

above, and a NO would indicate favoring another option (presumably #1?).

Literature

Cited

BROWN, L. AND D.

AMADON. 1968. Eagles, hawks, and falcons of the world. 2 Vols. Country

Life Books, Hamlyn, Middlesex, U.K.

FUCHS, J., J. A.

JOHNSON, AND D. P. MINDELL. 2012. Molecular systematics of the caracaras and

allies (Falconidae: Polyborinae) inferred from mitochondrial and nuclear

sequence data. Ibis 154: 520-532.

VUILLEUMIER, F. 1970. Generic

relations and speciation patterns in the caracaras (Aves: Falconidae). Breviora 355: 1-29.

Van Remsen, October

2012

__________________________________________________________________

Comments

from Zimmer:

“NO. Like Van, I don’t feel that I know

the species in Phalcoboenus well enough to properly inform my opinion on

this one. However, I do know the other

species (Daptrius ater, Milvago chimachima & M. chimango) well, so

here goes…Based on the molecular data, we clearly need to do something with chimango. Looking at morphology (particularly plumage

patterns), vocalizations, and ecology, it doesn’t make much sense to me to

shift chimango to Phalcoboenus, while retaining Daptrius (most

similar in plumage to Phalcoboenus, but sister to chimachima)

and Milvago (for chimachima). Therefore, I would say NO to the proposed

Option #3, and YES for Option #1 (merging all species from Milvago and Phalcoboenus

into Daptrius, which has priority), which would still be consistent with

the molecular data.

Comments

solicited from Nacho Areta: “This is a tough one to decide upon. I lean toward the single genus treatment: as

you said, they are all fairly open-area generalists and they all share their

slim wings (with a noticeable 'primary break') and long, slender tails, giving

them a very similar shape. Biogeographically, the only coherent group appears

to be Phalcoboenus sensu stricto, whose species seem to be less vocal

than Ibycter, Daptrius, or the Milvagos

and are restricted to cold Andean-Patagonian open habitats. I don't think that

any of the 'intermediate' options is reasonable, and I think that either a five

genera or a single genus option are the most palatable choices here. The

oddballs are the Milvagos (if they were not

here, I suspect everybody would be happy to have a single genus for the

black-and-white and painted-face members). Merging chimango into Phalcoboenus without

merging chimachima into Daptrius seems like the worst

possible option, as there are more (or as many) differences in plumage and

vocalizations between chimango-Phalcoboenus than between chimachima-Daptrius.

If separate genera are kept for chimango and chimachima,

then the same should be done for Ibycter, Daptrius, and Phalcoboenus.

If pushed hard, I would argue that merging them in a single genus would be more

informative than over-splitting this small group of birds into five different

genera. Looking at Falco, the merger becomes easier to digest. Yet

perhaps the best thing to do is to wait for a more solid phylogeny with

well-supported branches?

Comments

from Pearman: “I agree that Phalcoboenus is the

most coherent group, and this is a crucial point in relation to the taxonomy.

The four Phalcoboenus are robust, have three distinct age-related

plumages (the juveniles strongly resemble one another including australis),

adults always exhibit a white terminal band to (contra Nacho) a fairly

broad tail (unlike chimachima/chimango), which is often fanned

somewhat in flight, have a wing shape that is closest to Caracara but

with round-tipped primaries (unlike other caracaras), and their raucous grating

calls are very different from all the other genera/species mentioned, and they

are also less vocal in general terms. None of these features tally with chimango,

or chimachima or Daptrius making options 2 and 3 untenable. Daptrius and narrow-tailed Milvago

chimachima and chimango all produce different kinds of screaming

vocalizations. It is also noteworthy

that chimachima is the only species showing three very distinct

age-related plumages, unlike chimango and Daptrius. My personal

view is that we have three species which just don’t sit well with Phalcoboenus

and that there is too much information that would be forfeited with a rather

radical merger of all genera into Daptrius (option 1) which, by

itself, is an oddball caracara. Therefore, I believe that the erection of a new

genus for chimango (option 4) is a better solution.

I’m

not saying that I am going to write up a new genus, but I think this is a

better course of action than lumping into Daptrius, which is kind of an

easy way to sweep this problem under the carpet.”

Comments

from Nores:

“NO. First, I do not understand why all

the species are considered open-area generalists, when Daptrius and Ibycter are,

at least in Amazonia, forest birds? I have watched the two species on many

occasions and always in forests. Second, Milvago chimango and M.

chimachima have very similar behavior, and the young of M. chimachima

are virtually the same as adults of M. chimango. I have seen more than one experienced ornithologists

confuse the young of M. chimachima with M. chimango. When

I first saw M. chimachima young in Brazil more than 30 years

ago, I thought how odd that M. chimango reaches so far north. Anyway, if we consider mainly the molecular

analysis, then we can almost forget about the morphological. Fuchs’ tree, in

this respect, is one of the most illogical I've ever seen. I remember a

sentence by Robbins: ‘I was particularly

surprised with the molecular data, and I quickly realized that morphology and

vocalizations (except for mostly sister relationships) often lead to wrong

conclusions about relationships’. I vote option 1.

Comments

from Robbins:

“NO. Once again, a subjective decision

on how to deal with a monophyletic clade.

Why not put all in one genus, Daptrius.”

Comments

from Stotz:

“NO. I favor option 1, all in Daptrius.”

Comments

from Sergio H. Seipke:

”I

was prompted by Nacho Areta to submit for your consideration my views on this

subject. As I read previous comments made by others here, I found some

inconsistencies with my own observations. Most of what follows is the result of my own

work in the field and in museums, it has not been published elsewhere, and it

will be included in a book I am preparing (Seipke, S. H. Raptors of South America. Princeton

University Press.) I wandered beyond the point in question here (Transfer Milvago

chimango into Daptrius) as I deemed it necessary. I used

specific epithets standing alone to refer to individual species (instead of

using customary generic names) as to avoid confusion or ambivalences. Eventually, I chose not to be too formal at

times, as it is more fun.

“Americanus is truly way out

there on its own in most respects among the Neotropical caracaras. Adults and juveniles look virtually the same. They are extremely vocal (and loud!).

They are, for the most part, food specialists (wasps, bees, hornets) and show

very specialized feeding behavior (they fly by insects nests hitting them until

they fall and feed only when adult occupants have left). They have red feet. Their tails are obviously

graduated. Their flight profile (and behavior) is more akin to guans or

chachalacas than to any caracara. They are true forest birds, as they

occur in primary forests even far away from bodies of water or edges (although

they would wander to edges where deforestation advances rapidly or small

openings in continuous forest). Placing americanus into anything other

than its own genus will mask this significant differentiation.

“Carunculatus, megalopterus,

albogularis, and australis share several plumage traits

(developmental sequence) not present in the rest of the species in the clade

considered (Polyborinae sensu Fuchs et al. 2012, a

rather unfortunate name if I may say so, as Polyborus is a synonym

of Circus!). Namely, they all have four immature basic

plumages plus a definitive basic plumage. The first two immature basic

plumages are very similar (overall brown), and the reason why they have only

been described so far only for australis. The progression of character

states from basic I to basic IV is very similar for all four species (to the

point that all three truly continental forms can be readily told apart only

after well into the third year of age). In all four species, these two

'cryptic' juvenile plumages can be told apart by the shape of the primaries

(pointed in the first basic, rounded in the second basic), the coloration of

the bill, facial skin, and legs, and other minor differences. All four species are broad-tailed. These species can and do soar on thermals

without flapping (unheard of in other caracaras, except rarely in chimango).

All four species are ground dwellers and take carrion, insects, and other

animals they can catch on foot.

“Chimango also has only two

age plumages (juvenile and adult), and both are quite similar. But unlike

any other caracara (that I am aware of) chimango shows sexual dimorphism

in the coloration of bare parts of adults of different sexes.

“Although

ater, chimachima, and chimango (the

'screaming-caracaras') share overall proportions (all three being rather slim

and narrow-tailed), the first two are longer-tailed, shorter-winged birds (very

obvious on perched individuals) that fly on rather stable, linear trajectories,

even when flapping, whereas chimango, on the other hand, is very erratic

on the wing, even when gliding.

“Both

chimango and chimachima are rather catholic in their habitat use,

the former having populations very partial to (temperate) forests, the later

occurring in open grasslands and primary forest along major rivers too (e. g.,

sand banks). On the other hand, ater

is rather partial to major rivers in primary forest (where it is syntopic with chimachima).

Bottom line being, habitat is of limited use here.

“In

view of all-of-the above I think that the most informative treatment of the 'Polyborinae',

one that would not necessarily conflict with Fuchs et al. 2012, would be to

place ater and chimachima together in Daptrius and

leave everything else the same.

“Placing

chimango into Phalcoboenus would—well—destroy our notion of what

a Phalcoboenus is. Merging all into Daptrius s, from my

perspective, quite unnecessary, and artificially homogenizing. If you can have Ibycter americanus standing

alone, then you should be able to live with a Milvago chimango, too.

If you must place chimango into Phalcoboenus, please don't

label everything Daptrius. Thanks!"

Comments

from Pacheco:

“NO. I consider the comments of Sergio perfectly pertinent. For all these

reasons, I defend also that Chimango Caracara deserves a monotypic genus.

Something like "Protodaptrius" to be

published by someone.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“NO. Here, I tend to agree with Sergio: lumping everything into Daptrius produces

a virtually undiagnosable soup, and I tend to dislike the “toss the whole mess

into the same bag” approach, as it also implies sweeping a lot of useful

biological information under the rug. As

I am not very familiar with either Phalcoboenus or chimango (especially

their plumage sequences) and given the weak support for lumping the latter into

the former, I’d rather see a new genus for chimango if the differences

are as great as appears. Ibycter is

clearly OK as a monotypic genus. The

only real surprise to me is the relatively close relationship indicated between

Daptrius ater and Milvago chimachima. To me, they are very different birds in

habitat, sociality, plumage sequences and foraging: about the only similarities

are that they both “scream”, and a rather general resemblance in shape. Like Manuel, I certainly don´t consider D.

ater an “open country” bird. Hence,

I tend to favor option 4, though it would be nice to have better genetic data

to assure the placement of chimango.”

Comments

from Pérez-Emán:

“NO. I am familiar with both Daptrius ater and Milvago chimachima

but not much with Phalcoboenus and M. chimango, so comments from

Sergio, Pearman and Nacho are particularly useful to evaluate this proposal.

Fuchs et al. (2012) phylogenetic hypothesis does not really support merging chimango

into Phalcoboenus, so I would discard both options 2 and 3.

Additionally, as Gary mentioned, ater and chimachima seem to me

very different birds. I would favor option 4 as it will preserve basic

differences among this group of birds, but it is contingent upon the

availability of a name. Option 1, the other alternative, would group a somehow

similar species of birds including some variability unique to each current

genus. Differences between option 1 and 4 depends on how much variability we

would want to include into a genus.”