Proposal (562) to South

American Classification Committee

Recognize newly described Thryophilus sernai

Effect on South

American CL: This proposal

would add a newly described species to the list.

Lara et

al. (2012) discovered a new wren from the dry Cauca River Canyon, an

inter-Andean valley in Antioquia, northwestern Colombia, which is formed by the

northern sectors of

the Western and Central cordilleras and is enclosed at is mouth

by the rainforests of

the lower Cauca basin (Nechí Refuge). We described this population as a

new species. Our proposal is based on an integrative study in the Thryophilus group, including the results

of a comparative study of the distribution, vocalizations, morphology, and

phylogeny. The details can be found in the paper, but in short, we found the

following:

- Plumage

and morphology: The new species is similar to T. rufalbus but is paler overall and more cinnamon-brown rather

than rufous. It is also similar to T.

nicefori, but the latter differs in having a darker, colder brown

upperparts with faint black barring on the dorsum and upper tail-coverts. The

barring of the wings and tail differs decidedly among these three species and

not so much among different subspecies of T.

rufalbus (Fig. 1). Thryophilus sernai

is smaller in body mass and wing length than both T. rufalbus (all subspecies) and

T. nicefori; it has a smaller bill than T.

nicefori, and its tail tends to be longer than T. rufalbus.

Figure 1. Dorsal view

(left to right) of: Thryophilus nicefori,

Thryophilus sernai sp. nov., T.

rufalbus cumanensis and T. rufalbus

minlosi.

-

Vocalizations: The new species fall within the “Thryophilus” vocal group identified by Mann et al

(2009). Recordings of the new species can be examined in the Auk website or in here. Relative

to other taxa in Thryophilus, the new

wren’s songs have a richer repertoire of syllable types, shorter trills, lower

number of trill syllables, a distinctive terminal syllable with more

modulations, and higher spectral frequencies. Although there was some overlap

among Thryophilus taxa as expected in

their “acoustic space” characterized by multivariate analysis, songs of T. sernai are distinct but more similar

to those of nicefori and most

distinct from T. rufalbus. Two

discriminant analyses revealed statistical significant differences in songs

traits of T. rufalbus, T. nicefori, and the new taxon.

Valderrama et al. (2007, 2008)

previously documented the vocal behavior of T.

nicefori and demonstrated its vocal distinctiveness in relation to T. rufalbus.

-

Genetic differences: A phylogenetic analysis based on mitochondrial

DNA (cyt-b) sequence data confirmed

that the new taxon is a member of the genus Thryophilus,

and that it is evolutionary isolated from all other taxa in that genus

(Lara et al. 2012). Sequence

divergence of T. sernai averages the

following values in comparison to other taxa: T. nicefori (3.8%), T. r. castanonotus (3.8%), T. r. minlosi (3.6%), T. r cumanensis (2.7%), T. rufalbus rufalbus (5.4%), and T. rufalbus ssp. (3.7%). The new species, T.

nicefori, and T. rufalbus taxa

(except the last two) are reciprocally monophyletic (Lara et al. 2012, C. D. Cadena et

al., in prep.).

Recommendation:

Lara et al. (2012) concluded that the

population from the dry Cauca Canyon in Antioquia, Colombia, was an unnamed

taxon that merited species rank. The new species has unique vocal, plumage,

morphological traits, it is evolutionarily isolated from closely related forms,

and it occupies a small range, ecologically and geographically separated from

subspecies of T. rufalbus (Fig. 2).

Although reproductive isolation has not been assessed directly, some or all of

the divergent traits of the new species are likely involved in territory

defense, courtship, and mating, and given the current species-level taxonomy of

the group, which recognizes T. nicefori at the

species level, we believe species rank for the new form is warranted.

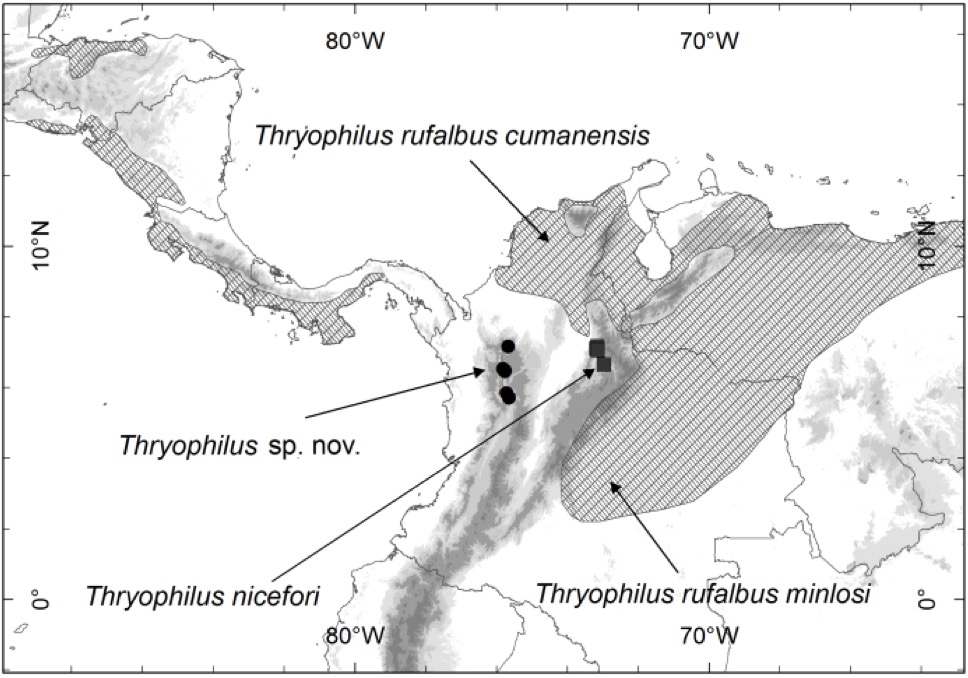

Figure 2.

Distribution of Thryophilus wrens: the new species (black dots), T. nicefori (gray squares), and T. rufalbus (shaded area) in north South America and Central

America.

Moreover, Lara et al.

(2012) stated that: “In comparison to the differences in plumage and song

existing between the two Thryophilus

species pairs known to be sympatric (pleurostictus–sinaloa and pleurostictus–rufalbus), T. sernai is arguably less different

from T. nicefori and T. rufalbus. However, greater

divergence is expected between sympatric pairs of species than between

allopatric pairs (Price 2008). Furthermore, in the context of currently

accepted species limits among members of the T. rufalbus complex (Valderrama et al. 2007, Remsen et al. 2012), T. sernai appears to be just as

divergent (or more so) from T. rufalbus

and T. nicefori as these two good

species are divergent from each other.”

We also realize that the widespread and polytypic wren T. rufalbus as currently defined is not

monophyletic and likely comprises multiple species and is in need of a formal

taxonomic revision. With that analysis pending, however, we believe that

recognition of T. sernai is a step

forward in terms of better describing the species-level diversity of this group

of wrens.

References:

Lara, C.

E., A. M. Cuervo, S. V. Valderrama, D. Calderón-F. and C. D. Cadena. 2012. A

new species of wren (Troglodytidae: Thryophilus)

from the dry Cauca River Canyon, northwestern Colombia. Auk 129: 537–550 – and references therein.

Valderrama,

S. V., J. E. Parra, N. Davila, N., and D. J. Mennill. 2008. Vocal behavior of

the critically endangered Niceforo's Wren (Thryothorus

nicefori). Auk 125:

395–401.

Carlos E. Lara, C. Daniel Cadena, and Andrés M.

Cuervo, October 2012

Comments from Remsen: YES. I

reviewed the paper at pre-publication stage and strongly support the

conclusions. As the authors noted, there

may be additional problems in rufalbus,

but that should not affect the decision herein.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“YES. The extent of the

morphological and vocal differences would appear to be consistent with

species-level recognition, especially when compared against the “yardstick” of

differences between other taxa currently ranked as species within the genus. Genetic distances between sernai and other congeners are also

consistent with such a ranking, and, recognition of sernai as a distinct species makes sense biogeographically.”

Comments from Stiles: “YES. Morphology,

vocalizations, and genetics are in accord with species status for sernai, regardless of what finally

happens in rufalbus (where minlosi at least might merit species

status).”

Additional comments from T. Donegan: “We recently assessed this species for the Colombian checklist (reference and link below). The text of our conclusions is set out below:

‘Antioquia Wren Thryophilus sernai

Recently described from the Cauca valley in Antioquia by Lara et al. (2012) as a species. This is clearly a new taxon, and we congratulate the discoverers. Any decision to assign it species rank (separately from allopatric Niceforo's Wren T. nicefori and T. rufalbus) at the present time is moot but we follow Lara et al. (2012)'s approach on account of this being a plausible long-term treatment. The new species is illustrated in Fig. 3 and its distribution is shown in Fig. 11. There are specimens (including the type specimens) and published sonograms and photographs of T. sernai from Colombia, so it can clearly be considered "confirmed" in the country to which it is endemic.

‘Recognition of this species has proved to be one of the more controversial issues considered in this series of annual papers on the Colombian checklist. In discussing species limits, Lara et al. (2012) considered that "it is likely that T. sernai has differentiated from T. nicefori and T. rufalbus to the point that they would behave as reproductively isolated units should they come into contact" citing differences in morphology, mtDNA and song. They claim in the diagnosis section that the new species is "distinctive in nine acoustic variables" and that it has a "richer repertoire of syllable types, shorter trills, lower number of trill syllables, a distinctive terminal syllable with more modulations, and higher spectral frequencies". However, there is no data available that would suggest that sernai is diagnosable to the usual 97.5% benchmark (Isler et al. 1999) used for supporting species rank determinations vocally. Their vocal "diagnosis" is based on the Kruskal-Wallis test (in Lara et al.'s table 3), which determines the likelihood that data sets come from populations with different medians, but says nothing about the extent of differences or diagnosability. No standard deviation data is presented, so there is no way of reverse engineering the data for these purposes. In studies of other taxa, pairwise mean differences have sometimes been found consistent with miniscule differentiation and low levels of diagnosability (e.g. Donegan 2012a). There is c.91% differentiation and considerable overlap based on recorded values in multivariate space (their figure 6) suggesting that voice is not diagnostic. The authors' claim of shorter trills is not borne out by the illustrations in the paper (2, 5 or 9 notes in the trills in Fig. 3 for sernai, versus 2-8 in other taxa). The claim of a richer repertoire of syllables is subjective. Differences in modulation of the final note and overall maximum acoustic frequency are true of some but not all examples of songs in their figure 3, so again are not diagnostic. Song can be learned in oscines such as wrens, so the possibility that differences may be cultural and perhaps could be eliminated by learning if populations were to come into contact cannot be easily dismissed. No mention is made of whether sernai responds to playback of related species or how.

‘Lara et al. (2012) note that the rufalbus group requires revision but also consider that: "the paraphyly of species is an expected outcome of speciation processes in which differentiation occurs in peripheral populations". There is at least one documented instance of this phenomenon in Troglodytidae (Troglodytes cobbi: Campagna et al. 2012). However, T. cobbi is strikingly different in its ecology (absence from human modified habitats) to T. aedon, whilst T. sernai is a differently marked version of T. rufalbus / nicefori in a different dry valley. It has a more proximate distribution to rufalbus and nicefori than T. cobbi does to T. aedon. New taxon sernai is less differentiated in its mtDNA than some other named populations in the rufalbus group are from one another (2.5-3.5% between nicefori, sernai and proximate rufalbus; compared to 6.8% between nominate T. rufalbus and subspecies castonotus). In conclusion, it seems implausible that a rational treatment for the rufalbus group involves only T. nicefori and T. sernai being afforded species rank. At least, nominate rufalbus and its relatives would also appear to need splitting from the southern rufalbus taxa.

‘Despite these concerns, we recognise T. sernai on account of its broadly similar levels of vocal

differentiation from rufalbus to that

of nicefori, which is historically widely recognised as a species and shows

similar vocal differentiation from other taxa (Valderrama et al. 2007). Long-term, splitting sernai, nicefori and some other rufalbus

taxa would seems a reasonable approach. In molecular phylogenies, sernai (like T. nicefori) is nestled within T.

rufalbus and is similarly differentiated to T. nicefori. Moreover, it would be a questionable outcome to

see a potentially threatened taxon like this, with a unique distribution go

unprotected whilst an open-ended taxonomic revision takes place. A revision of species limits in the T. rufalbus group as a whole is urgently

called for however.’

“For such an

accessible population, Lara et al. (2012)'s lack of mention of playback

experiments seems anomalous and raises most questions. The results of playback studies were key in

affording species rank to Henicorhina

negreti, the only other recently described wren species occurring in

western Colombia. This new species was

described by Salaman et al. (2003), a paper highly relevant to the sernai description but not cited. It seems unimaginable that the authors would

not have played sernai an MP3 of nicefori and/or rufalbus given the widespread and low-cost use of Ipods and similar

devices for playback nowadays and easy availability of recordings of these

other species. Did sernai respond? T. rufalbus has never been that difficult

a bird, and now T. nicefori is also

accessible in a few known localities. Do

they respond to sernai? How? Is this relevant to species limits?

“There would not

seem any reason of principle as to why a species should not be recognised in a

paraphyletic group like this, even if the description increases overall

paraphyly, where the treatment is defendable as a long-term approach and

differentiation of the study taxon is consistent with that of other

species. The following might be a less

speculative justification: "The

paraphyly of species has been found in some better-studied groups and is an

expected outcome of historical processes for nomenclature and taxonomy in

groups which only recently have been subject to vocal and molecular

investigations".

“Reference: Donegan, T.M., Quevedo, A., Salaman, P. &

McMullan, M. 2012. Revision of the status of bird species occurring or reported

in Colombia 2012. Conservación Colombiana 17: 4-14.

http://www.proaves.org/proaves/images/RCC/Con_Col_17_1-14_Actualizacion_Listado.pdf”

Comments from Cadena: YES (I am

a coauthor of the description). Regarding the "anomaly" noted above,

I do not know if people have played the song of nicefori and rufalbus to sernai; I only saw the bird in life for

the first time last month. I bet people probably have, however, and considering

that nicefori responds to songs of rufalbus and that wrens may often be

interspecifically territorial (good published examples in Thryothorus and Henicorhina),

I bet that sernai likely responds.

What would that mean? This is something one cannot tell without carefully

designed reciprocal experiments (its not simply a matter of taking an iPod once

to the type locality), which someone should probably carry out at some point

when a much-needed revision of the whole rufalbus

complex is undertaken. I will leave it to readers and to other committee members

to evaluate whether the additional criticisms are valid. I stand by our

conclusions that, taken together, and relative to the existing species-level

taxonomy of the group, sernai is best

ranked as a species-level taxon.”

Comments from Nores: “YES. Vocalizations, morphology, and especially the genetic differences match the species status for this taxon.”

Comments from Robbins: “YES. All data support the recognition of T. sernai as a species.”

Comments from Stiles: “YES. Recognizing sernai as a distinct species (at least pending a general in-depth

study of the entire rufalbus complex)

seems the best option.”

Comments

from Pacheco:

“YES. I also agree that treatment as a

species is the best choice for this complex.”