Proposal (566) to South

American Classification Committee

Treat Geotrygon purpurata as a separate species from G. saphirina

Proposal:

This proposal, if it passes, would result in G. purpurata being split from G.

saphirina, a treatment accepted by several other authorities, including

several major publications on pigeons over the last decade and others listed in

Donegan & Salaman (2012).

Discussion:

This split was rejected in proposal 105. This was back in 2004, before sources like

xeno-canto were really available or had good samples and consistent with the

SACC's then approach to other "field guide splits" around this time. Most committee members cited a lack of vocal

data supporting the split, and no dissenting comments in support of the split

are evident. There are

two new publications relevant to this issue published in the last couple of

years, and a further relevant paper was overlooked in 2004.

Molecular data:

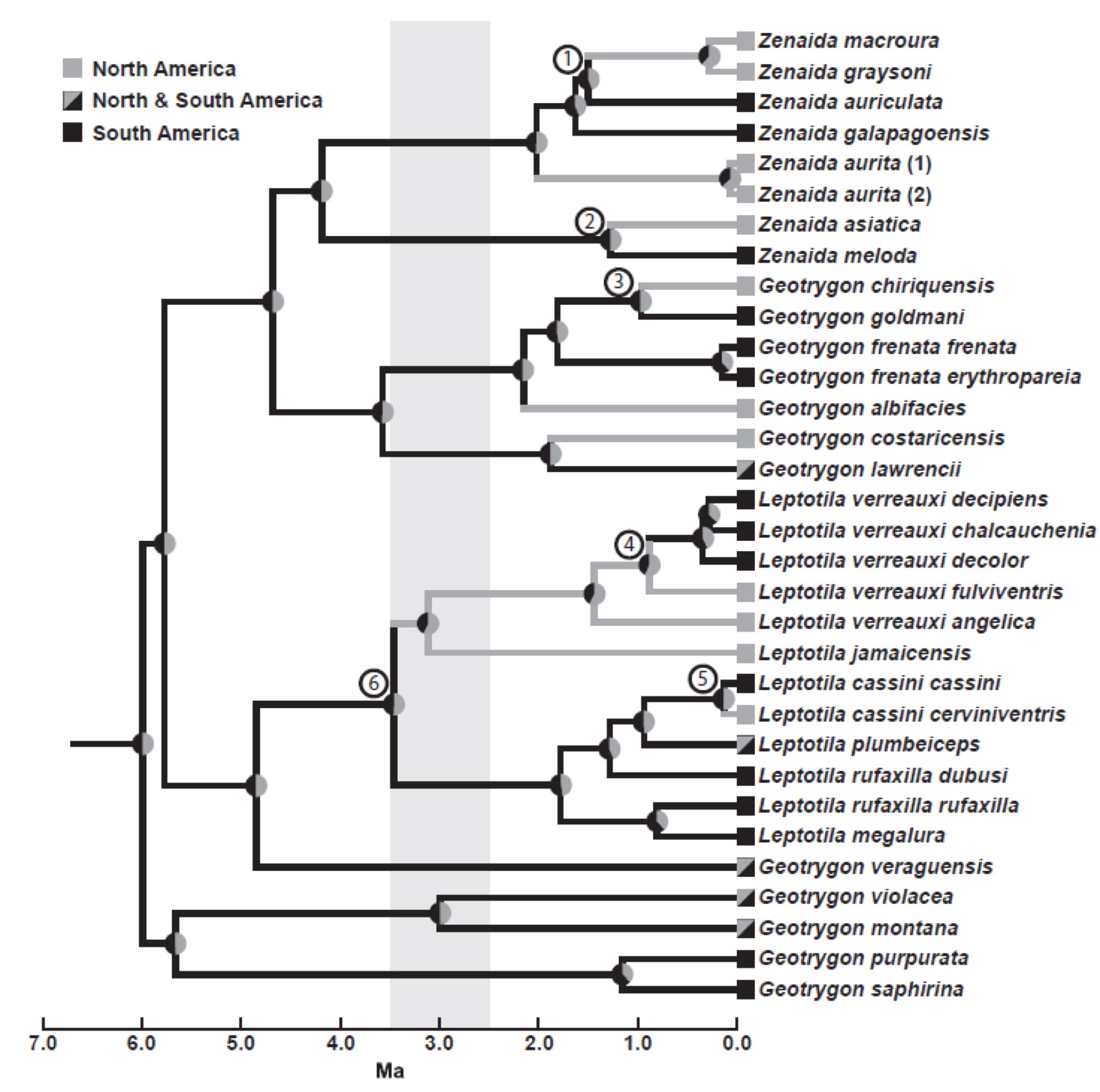

Brumfield

& Capparella (1996: http://www.museum.lsu.edu/brumfield/pubs/brum96.pdf),

using three samples of each group, found unusually high divergence between purpurata and saphirina for lowland conspecifics with a Chocó / Amazonian

distribution. More recently, Johnson

& Weckstein (2011) studied a single Ecuadorian purpurata and single Peruvian saphirina

in a phylogeny including good sampling of new world pigeons. They found strong support for a sister

relationship and moderate (modeled c.1.2

million years) differentiation, consistent with that observed between samples

of Russet-crowned Quail-Dove Geotrygon

goldmani & Chiriquí or Rufous-breasted Ground-Dove G. chiriquensis and those between nominate Grey-fronted Dove Leptotila rufaxilla & Yungas Dove L. megalura, but also consistent with

intraspecific variation in widespread Leptotila

verreauxi. One of their BEAST

chronogram-based phylogenies is set out below.

Note these two Geotrygon species

at the bottom of the tree, and the relative depth of the branch.

Neither

studies reject monophyly for the combined group (and the latter study found

strong support for this). But both

studies show a relatively deep division, consistent with Chocó/Amazonia splits

generally and those between several Neotropical pigeon species.

Vocal data

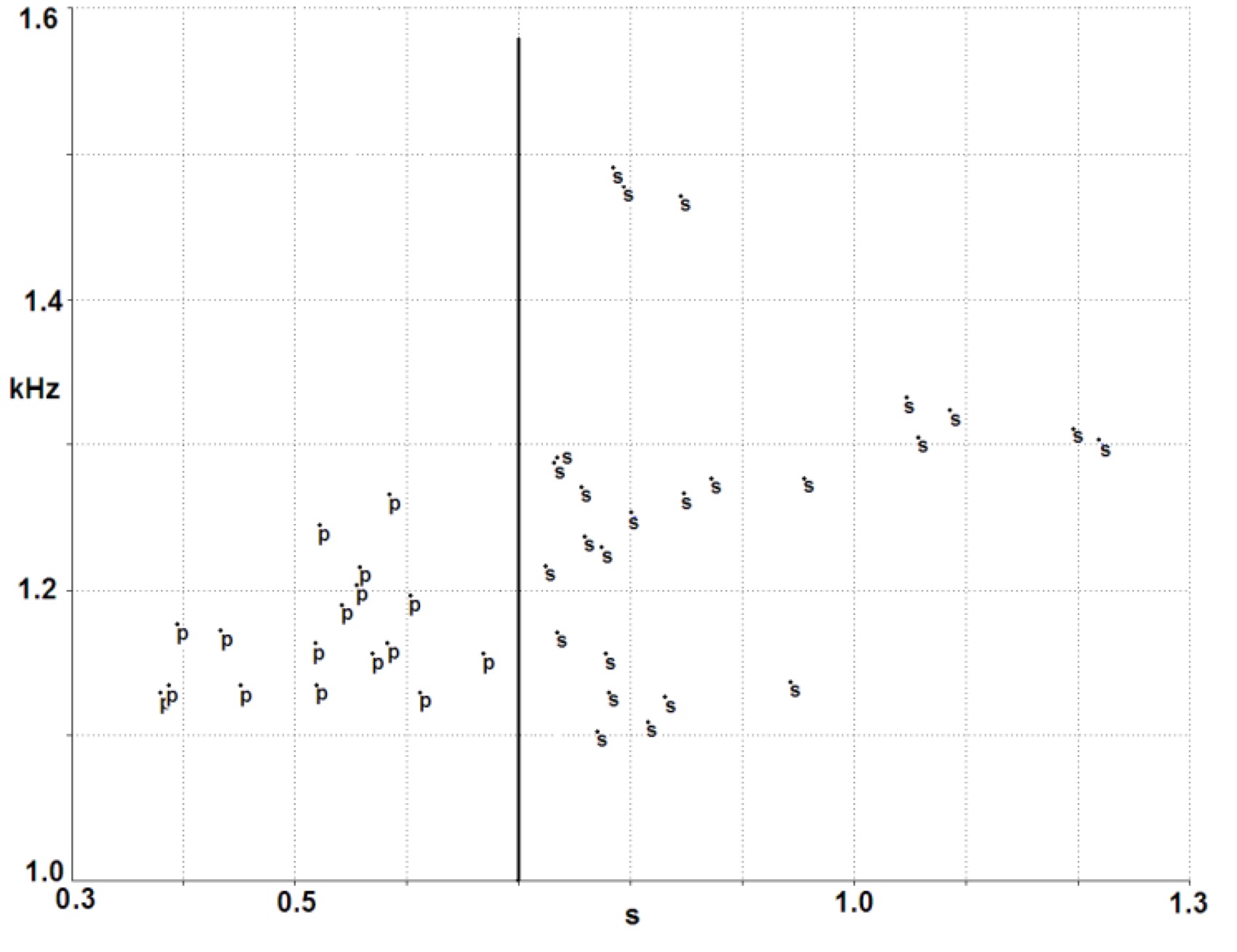

Donegan

& Salaman (2012: link below) published various data on these pigeon

species' natural history, voice and conservation, and included a rare

photograph of purpurata in life by

Juan Carlos Luna. We measured two

acoustic variables and found no overlap for the length of the main note in

songs between saphirina and purpurata (see figure reproduced

below). The differences are

statistically significant, but despite there being no observed overlap, the

data did not meet the Isler et al.

'97.5% using t-distributions'

diagnosability test. Acoustic frequency

also varies between the taxa, with statistical significance found, but not

diagnosability. G. saphirina (in some but not all recordings) varies the frequency

of songs but G. purpurata has flat

notes in all recordings. It is this

variability of frequency that past transcriptions of vocal differences in field

guides seem to have concentrated on as a difference, but this feature is

non-diagnostic: saphirina also gives

flatter calls. Song length does however separate out the sample

fully based on recorded data. It would

be speculative to conclude whether, with a greater sample size, the ideal 97.5%

diagnosability test would be met or not.

The vocal differences are, however, very real and substantial, and have

gone largely overlooked or misunderstood in the literature until Salaman &

Donegan (2012). See our figure 3,

reproduced below (song length on x

axis, frequency on y axis; p=purpurata; s=saphirina).

As

discussed in our paper, given the way in which these songs are made, by birds

inhaling a lot of air, expanding the chest, and then exhaling through their

nostrils without bill movements (see this video:

http://ibc.lynxeds.com/video/sapphire-quail-dove-geotrygon-saphirina/bird-singing-forest-while-perched-eye-level),

such vocal differences seem likely to be constrained by physiological factors

and not a result of learning.

The two

species seem to have different elevational ranges, and, hence one assumes,

ecological requirements. In particular, purpurata is a foothill bird that has

not been recorded on the Chocó "floor" whilst saphirina is found in western Amazonia.

The molecular and vocal data seem

consistent with other pigeon splits. The

split passes Tobias et al.'s "species scoring tests" also. A subsequent communication with Nigel Collar

revealed that their team last year independently assessed purpurata as (just) meeting the "species scoring test",

disregarding vocal differentiation data (which were not available to

them). We were more conservative in

assessing plumage scores and had purpurata

'crossing the line' as a result of 2 points out of 3 for the highly

differentiated and statistically significant (but not statistically

diagnosable) vocal differences. Neither

the paper nor this proposal is intended as an endorsement of this score system,

but it is a useful further indication for allopatric birds like these. On the basis of all the above, my own view,

and that of all our team who work on the Colombian checklist, is that these

molecular and vocal data tip the balance in favour of treating purpurata separately under a

conservative BSC approach. We appreciate

that really hardcore Petersian lumpers could legitimately take another view

given monophyly and failure to meet the toughest statistical tests of

diagnosability.

We also

discussed the conservation status of purpurata. Although not relevant to taxonomic determinations, it is

perhaps of note that (whether lumped or split), these are both threatened

forest-dependent birds, VU when lumped based on the recent papers on Amazonian

deforestation rates; and with G.

purpurata recommended in our paper for EN treatment if split. This decision is, therefore, not solely of

relevance to listers or bird checklist accuracy fanatics.

Vernacular names: Quoting from our paper: "Hellmayr

& Conover (1942) used the name Purple Quail-Dove, which is appropriate

given that this is the most purple Geotrygon. However, this name seems

to have been overlooked in the recent literature in favour of Indigo-crowned

(e.g. Ridgely & Greenfield 2001, Restall et al. 2006)." "Purple" for purpurata is a nice name and transliteration, which mirrors

"Sapphire". Perhaps a separate

proposal on that issue is needed if this passes? We would suggest retaining saphirina's existing vernacular name

(Sapphire) given its appropriateness in light of plumage and the scientific

name, relative sizes of distributions (this name would still apply to by far

the greater part of the old combined range) and history of usage in other

sources.

References:

Brumfield, R. T. & Capparella, A. P. 1996.

Historical divergence of birds in north-western South America: a molecular

perspective on the role of vicariant events.

Evolution 50(4): 1607-1624.

Donegan,

T.M. & Salaman, P.G.W. 2012. Vocal differentiation and conservation of

Indigo-crowned Quail-Dove Geotrygon

purpurata. Conservación Colombiana 17:

15-19. http://www.proaves.org/proaves/images/RCC/Con_Col_17_15-19_Geotrygon.pdf

Johnson, K.P. &

Weckstein, J. 2011. The Central American land bridge as an engine

of diversification in new world doves. Journal of Biogeography 38: 1069-1076.

Other

papers mentioned are cited in the above.

Thomas Donegan, November 2012

Comments from Robbins: “YES, given the

plumage and genetic (especially when compared to other recognized Geotrygon species) data. The relatively minor differences in

vocalizations do not concern me, as most Geotrygon

primary vocalizations sound very similar.”

Comments from Stiles: “YES, given the

genetic and biogeographical information; the vocal data are also suggestive, if

not wholly conclusive.”

Comments from Pacheco: “YES, from the new genetic and vocal data.”

Comments from Zimmer: “YES. We now have some genetic data plus some more suggestive (if not 100% conclusive) vocal data to hang our hats on – something that was lacking when voting on the earlier proposal.”

Comments from Pérez-Emán: “YES. I think genetic and vocal data, when analyzed within the genus context, tip the evidence in favor of recognizing these two species. It also makes sense biogeographically.”

Comments

from Remsen: YES, barely.

Using comparative genetic distance as a yardstick for species ranking is

inherently flawed, despite its seductive appeal. Subjectively, however, plumage and vocal

differences between the taxa are consistent with the slight differences in

these features between close relatives in this lineage of doves (which includes

Zenaida and Leptotila). Finally, these

were treated as separate species by Hellmayr & Conover (1942), and I

convincing rationale for their merger was never presented as far as I know.”

“Concerning

English names, I favor Donegan’s proposed names, i.e. Purple and Sapphire, for

the reasons he mentioned. This is not

the case of a new split requiring two new names – this is a “re-split” of two

taxa treated as separate species previously, when ‘Sapphire Quail-Dove’ was

restricted to G. saphirina. Proposals for alternatives are welcomed as

always.”

Comments

from Nores: “YES,

barely. Plumage differences are not so noticeable and neither are the genetic

differences.”