Proposal (607.1) to South American Classification Committee

Results

of the voting on 607 (see below) were that 5 of 8 votes favored option 1, i.e.

no change in species limits but a transfer of one subspecies to another

species.

Therefore

607.1 becomes a YES/NO proposal as follows:

1. Retain three species of trumpeters, transferring ochroptera

from P. leucoptera to P. crepitans to avoid a paraphyletic P.

leucoptera.

(Van Remsen, 23 January 2015)

Comments from Remsen: “YES. This is the safest course given the lack of

direct studies of interactions at contact zones and lack of study of isolating

mechanisms. I am even a little reluctant

to make the subspecies transfer because this is based on an mtDNA gene

tree. I think Oppenheimer and Silveira,

and Ribas et al., have done a terrific job in setting the stage for more

focused and thorough sampling of populations in this group. The preliminary data from the headwaters all

point towards multiple species, and I look forward to one transect through one

of the potential contact zones for solid data on which to base a decision. Because Psophia

are of conservation concern, I think that this is a case in which a series of

photographs might be sufficient establish the pattern of plumage variation

across a transect. Pegan and Hruska did

a great job pulling these data together to make it easy for us or anyone else

to get a clear and quick grasp of the problem.”

Comments from Stiles: “YES.

I agree with Van on this one ... more

intensive genetic analyses and attention to vocalizations seem warranted. Incidentally, I find Bret’s observation of

singing by a trumpeter in captivity interesting – a source of vocal data? Has

anyone tried mirror-image stimulation with these birds? If males, it might work!”

Comments from Jaramillo: “NO – I am going to go contrarian on

this one, largely to state that there is something here in this paper that

would be good to acknowledge. I am not sure that the splitting up of Psophia will occur in this vote, but

keeping things as they are seems less palatable today to me, than beginning to

incorporate some of these findings.”

Comments

from Pacheco: “YES. In view of

insufficient sampling present in Ribas et al. and Oppenheimer/Silveira, it is

not appropriate changing boldly the arrangement of trumpeters.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

““YES. I think we have to do this given

the analysis of Ribas et al (2012), and given that the original Proposal 607 on

changing species limits in Psophia

failed to pass. However, like Alvaro, I

think there is more that we should have done with the original proposal

regarding species limits.”

Comments from Areta:

“YES.

This is the minimum necessary change to make our classification consistent with

phylogenetic data. Given insufficient sampling and meager biological data, this

is clearly a conservative change. As stated by others, the data presented by

Oppenheimer & Silveira (2009) and by Ribas et al. (2012) suggest that there

are more species-level entities in Psophia,

but critical information is needed before this move can be made with

confidence.”

=====================================================

Proposal (607) to South American Classification Committee

Recognize a

new species-level taxonomy of trumpeters (Psophiidae)

Effect on SACC: This

proposal reviews the taxonomy of the trumpeter family (Psophiidae). If passed, multiple new species would be

recognized: the revision we recommend would split Psophia viridis into

three species, P. viridis, P. dextralis, and P. obscura. Psophia crepitans napensis would be

elevated to species status as P. napensis, and P. leucoptera

ochroptera would be elevated to species status as P. ochroptera.

Background:

Psophiidae –

the trumpeters -- is a family in the Gruiformes currently consisting of three

species: P. leucoptera, P. crepitans, and P. viridis. New genetic and morphological evidence

suggests that this arrangement underestimates trumpeter diversity, as many (or

all) of the eight trumpeter taxa could be elevated from subspecific to species

status. Here we consider the evidence for how these eight taxa should be

classified.

Current

taxonomy recognizes the following taxa as species. The Gray-winged Trumpeter (P.

crepitans) occurs north of the Amazon River and is currently composed of two

subspecies, Psophia crepitans crepitans and P. crepitans napensis (hereafter

referred to as P. crepitans and P. napensis). The Pale-winged Trumpeter (P. leucoptera)

occurs south of the Amazon River and west of the Madeira River and includes two

subspecies, P. leucoptera leucoptera and P. leucoptera ochroptera (hereafter

referred to as P. leucoptera and P. ochroptera). The Dark-winged

Trumpeter (P. viridis) is endemic to Brazil and has three widely

recognized subspecies, P. v. viridis, P. v. dextralis, and P.

v obscura. A fourth subspecies, P.

v. interjecta, has generally not been considered valid. Hereafter these taxa will be referred to as P.

viridis, P. dextralis, P. obscura, and P. interjecta. The taxa within the P. viridis complex

were recently reviewed by Oppenheimer and Silveira (2009).

Trumpeters

are ground-dwelling birds that live in family groups that defend territories

together and breed cooperatively (Sherman 1996). They are poor fliers and prefer to walk

around obstacles, including water, rather than fly over them. They have been

reported flying over small streams and, in rare cases, swimming to escape

danger, but appear to seldom attempt to cross rivers. Hence, rivers are thought

to be an important barrier to trumpeter movement and therefore gene flow

between trumpeter populations. Trumpeter taxa are morphologically similar,

predominately distinguished by the color of their hind-wing patch (or mantle);

thus their English names, Gray-winged, Pale-winged and Dark-winged. This

hind-wing patch appears to be important in maintaining visual contact between

flock members and may play a role in displays (Sherman 1996).

Genetic

Data:

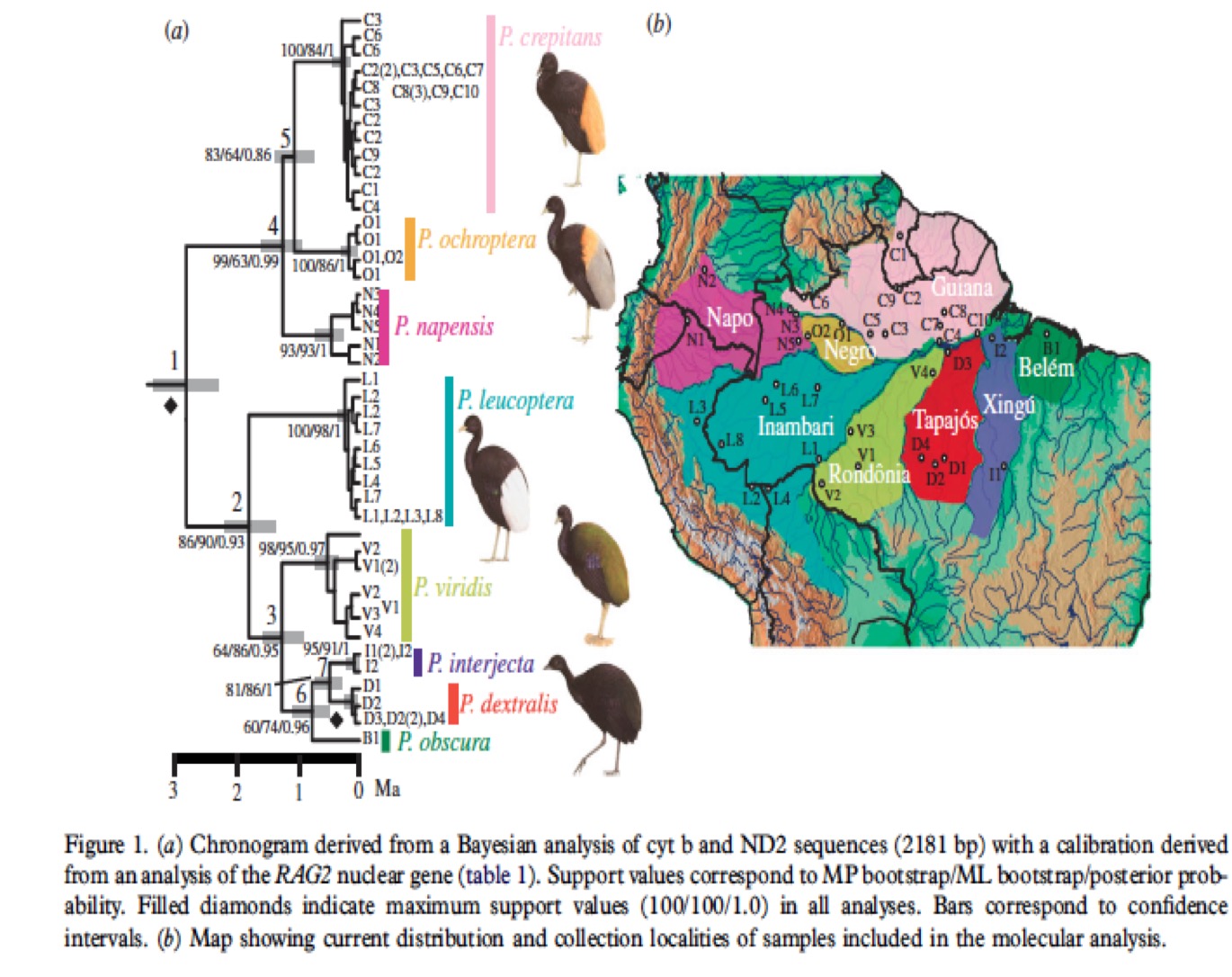

Ribas et al. (2012) sampled and sequenced

genetic mitochondrial genes (cyt b and ND2) from 62 individuals, including

representatives of all species and subspecies of Psophia.

Phylogenetic

Analysis:

Ribas et al.

used a Bayesian analysis to build a phylogenetic tree for all Psophia taxa

(Figure 1). This tree identified the eight trumpeter subspecies as monophyletic

entities, and found P. crepitans and P. leucoptera, as currently

defined, to be paraphyletic. Support values were high for branches separating

taxa, with the exception of weaker support for their node 5, which separates P.

crepitans and P. ochroptera. The Ribas phylogeny contains two main clades,

one corresponding to taxa north of the Amazon River and one corresponding to

taxa found south of the Amazon River. In

the Northern clade, P. napensis was found to be sister to P.

crepitans and P. ochroptera, while in the Southern Clade, P.

leucoptera was sister to the four subspecies currently subsumed within P.

viridis, with P. v. viridis sister to the remaining three taxa. In

addition, P. obscura was found to be sister to a clade comprised of P.

dextralis and P. interjecta (Ribas et al. 2012). This phylogeny

demonstrates clear differences between taxa but little to no structure within

them, indicating high gene flow within populations and lack of gene flow

between them. Psophia viridis

(i.e., the population formerly called P. viridis viridis) is somewhat of

an exception, showing higher nucleotide diversity and signs of structure in its

haplotype network; still, no evidence of hybridization with any other taxa was

found in this case.

Vocal Data:

There are no

vocal data studies that can inform this proposal. The three current trumpeter species seem to

produce similar vocalizations, but this has not been well studied.

Morphological

Data:

As

previously described, all trumpeters are somewhat similar in appearance,

differing mainly in the color of their wings (mantle) and lower throat (Sherman

1996).

Oppenheimer and

Silveira (2009) analyzed the P. viridis complex and found three

morphologically distinct groups defined by plumage color (based on a set color

key) and geography: the taxa are each unique to regions separated by large

rivers. Their proposed taxa are defined below:

1) P.

viridis: Found from the region between the Madeira and Tapajos rivers,

individuals have the distal and intermediate parts of the mantle Parrot Green,

with the proximal portion Dark Green. These individuals have a conspicuous

purple iridescence on the lower neck and wing.

2) P. dextralis:

Found between the Tapajos and Tocantins rivers, individuals have a mantle whose

distal portion is Olive Green, and whose intermediate and proximal portions are

Very Dark Brown. The lower neck and wing have either discrete or absent purple

iridescence.

3) P.

obscura: Found from eastern Tocantins to Maranhão, individuals had the

distal and intermediate portion of the mantle consistently Dark Green, with the

proximal portion Dark Brown. Their lower necks and wings had very much reduced

or no purple iridescence.

These

morphological differences, in conjunction with the absence of known contact and

hybridization zones, support the hypothesis that these taxa are genetically

isolated from one another and thus likely to retain their genetic and

phenotypic uniqueness in the future. In addition, this fact is supported by the

lack of clinal variation found in these morphometric parameters, both within

and across subspecies of Psophia (Oppenheimer and Silveira 2009). These

criteria coincide with those utilized by the British Ornithologists’ Union when

recognizing species based on morphology alone (Helbig et al. 2002). Oppenheimer

and Silveira found that P. interjecta was not unambiguously diagnosable

from P. dextralis based on plumage morphology so they recommend that it

be considered a subspecies of P. dextralis. However, genetic data (see

Genetic Data above; Ribas et al. 2012) shows evidence of structure between

these two populations, perhaps indicating an absence of gene flow between them.

Contact

zones:

These eight

taxa are allopatrically distributed and separated by large rivers, which likely

form isolating barriers to members of this ground-dwelling family. Nonetheless, the headwaters of these rivers,

where rivers are relatively narrow, may allow contact between different

populations.

Oppenheimer

and Silveira studied specimens from the headwaters of rivers that run between

the populations (where the rivers would serve as less effective barriers) and

found no evidence of clinal variation or intergradation in their mantle and

neck coloration. This observation suggests there is no gene flow between the

populations even where the rivers may serve as less effective barriers and the

populations may be in contact. Similarly,

Sherman (1996) reported that P. ochroptera may be in contact with P.

napensis at the western part of its range, but that there is no evidence

that interbreeding occurs there. Finally, Ribas et al. also studied specimens

collected from headwaters areas and found no mtDNA evidence for inter-taxon

hybridization in these areas. They also

found little geographic structure within populations, and that in some

instances specimens from headwaters had the same haplotypes as those of the

same populations from near the river mouths.

This indicates that there is little isolation within these taxa, but

strong isolation between them (see also Genetic Data section above).

Conclusions:

This

proposal is largely based on the results of two studies. Oppenheimer and Silveira (2009) reviewed

morphological evidence surrounding species limits in Psophia viridis;

Ribas et al. (2012) used mitochondrial DNA to examine all three of the

current trumpeter species.

Taken in

conjunction with these birds’ natural history, the two studies complement each

other: Ribas et al. (2012) provides genetic support for the eight

trumpeter taxa and Oppeneheimer and Silveira (2009) shows that in the case of

the P. viridis complex, genetic differentiation is accompanied by

morphological divergence that suggests reproductive isolation and lack of

hybridization. We suggest that the morphological evidence presented in

Oppenheimer and Silveira (2009) can inform our inferences based on the Ribas

mtDNA phylogeny. Specifically, this bears on the question of whether distinct

taxa with rather shallow branch lengths ought to each be considered species or

whether subspecies affinities merely need to be rearranged. The fact that

Oppenheimer and Silveira’s morphological isolation data largely agrees with the

genetic conclusions of Ribas et al. suggests that P. viridis should be

split into multiple species; moreover, in this case they report no evidence of

clinal variation at headwaters, indicating that color, especially mantle color,

may be an important indicator of isolation.

This idea is further supported by the fact that the colored mantle

appears to be important in the social behavior of the species (Sherman 1996).

Given this

conclusion, it does not seem advisable to consider P. crepitans and P.

ochroptera as the same species given their readily diagnosable differences

in mantle coloration. Recognizing these

taxa as species also supports the recognition of P. napensis as a

species despite the fact that it is very similar in coloration to P.

crepitans; to do otherwise would create a paraphyletic species.

The one area

where morphological and genetic taxonomic recommendations differ is their

treatment of P. interjecta. This

proposed subspecies is usually not recognized and has been thought to be an

intergradation between P. dextralis and P. obscura (Sherman

1996). While Oppenheimer and Silveira

find it too similar to P. dextralis in plumage morphology to be

diagnosable as a species, Ribas et al. find genetic support for its distinction

as a taxon. This further strengthens the idea that no clinal variation exists

between trumpeter populations separated by large rivers; if P. interjecta

is a valid taxon and not an intergradation, no examples of this sort of clinal

variation exist. Ribas et al. found little to no mtDNA structure within each of

the eight taxa but strong structure between them, and use P. interjecta and

P. dextralis as particular examples of this result. However, given the

lack of morphological evidence, the relatively few samples of this taxon used

in the genetic study, and the shallow branch lengths of these taxa’s node on

the tree shown in Figure 1, it is less clear whether this taxon ought to be

elevated to a species or whether it should be recognized as a subspecies of P.

dextralis.

English names: Should this

proposal be passed, we leave it up to the SACC to determine English names of

the resulting species.

Taxonomic

possibilities:

There are quite a few permutations

of taxonomic possibilities because of the number of taxa involved, but we have

identified three possibilities that appear most reasonable given the new

genetic and morphological data:

1. Retain three species of trumpeters, transferring ochroptera

from P. leucoptera to P. crepitans to avoid a paraphyletic P.

leucoptera.

2. Recognize

seven species of trumpeters; recognize P. napensis and P. crepitans

and elevate all P. viridis subspecies to the species level except for P.

interjecta, based on lack of morphological evidence for this latter taxon’s

distinctness from P. dextralis; classify interjecta as a

subspecies of P. dextralis.

3. Recognize

eight species of trumpeters; all those described in the above option, and

additionally recognize P. interjecta based on lack of evidence of

structure within the taxon (contrasting with its genetic separation from P.

dextralis) and its geographic separation from P. dextralis by

a large river.

Recommendation:

We suggest that recent morphological

and genetic evidence is sufficient to warrant a novel species-level phylogeny

for trumpeters. As described above, we consider the evidence sufficiently

strong to support breaking trumpeters into multiple species instead of

rearranging subspecies into the currently recognized species. We therefore

recommend a “No” vote on Option 1. Instead, available evidence supports

recognizing at least seven species of trumpeters, and we therefore recommend a

“Yes” vote on Option 2. We are agnostic on the question of whether P.

interjecta ought to be elevated to full species status, but suggest that

this approach (Option 3) also a valid possibility.

Literature

Cited:

Helbig, A.J., Knox, A.G., Parkin, D.T., Sangster, G., & Collinson,

M. 2002. Guidelines for assigning species rank. Ibis, 144(3), 518-525.

Oppenheimer, M., & Silveira, L. F. 2009. A taxonomic review of the

dark-winged trumpeter Psophia viridis (Aves: Gruiformes: Psophiidae). Papeis Avulsos De Zoologia, 49(41), 547-555.

Ribas, C.C., Aleixo, A., Nogueira, A.C.R., Miyaki, C.Y., & Cracraft,

J. 2012.

A palaeobiogeographic model for biotic diversification within Amazonia

over the past three million years. Proc.

R. Soc. B 279, 681-689.

Sherman, P.T. 1996. Family Psophiidae (trumpeters). Pp. 96-107 in: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A.,

& Sargatal, J. eds. (1996). Handbook of Birds of the World. Vol. 3.

Hoatzins to Auks. Lynx Edicions,

Barcelona.

Teresa Pegan and Jack Hruska, December 2013

========================================================

Comments from Stiles: “YES to proposal

1. The splitting of P. viridis into

multiple species seems a bit premature, as the genetic distances are not all

that great. Moreover, trumpeters are very vocal birds that spend most of their

time in dark forest understory; hence the importance of mantle color as an

isolating mechanism (vs. vocalizations) may be uncertain; here I think that

voice might be more important, and that some sonograms (hopefully with at least

some playback experiments) could help to shift the balance toward splitting up

the viridis complex, given that all

forms are apparently allopatric.”

Comments from Nores: “YES, to proposal 2. However, I agree

with Gary that voice might be very important, and that some sonograms and some

playback experiments could help especially in the viridis complex.”

Comments

from Zimmer: “YES. I’m conflicted on the specifics. I think that Proposal 1 is the minimum that

needs to be done – the genetic data are clear for removing ochroptera from leucoptera. I agree with Gary that vocalizations seem

likely to be of more importance than slight differences in mantle color. Unfortunately, I’m guessing that it is going

to be a long time before anyone comes up with meaningful sample sizes of

auditory recordings of each of these taxa.

As we have already seen with attempts to evaluate geographic differences

in vocalizations in Ortalis, it can

be very difficult to assess vocal differences in Psophia due to variation from one recording to the next in the

number of individuals vocalizing (and this usually being unknown). Also, I can’t help but think that the plumage

differences between ochroptera and crepitans/napensis have to be important when it comes to signal recognition,

mate choice, etc. – unlike the relatively

conservative plumage distinctions between the various taxa in the viridis complex, ochroptera versus anything else is pretty striking. If we treat ochroptera as a different species from crepitans, then we also have to split crepitans and napensis to

avoid a paraphyletic situation within crepitans. If we split those two taxa, then that opens

the door for recognizing the various populations of viridis as specifically distinct, an outcome that may be the

correct way to go, but one for which I am less enthusiastic (lacking vocal

data) than I am about splitting ochroptera

and crepitans. Despite the short branch lengths, I do think

that all of these taxa are likely on independent evolutionary trajectories,

especially given the seeming effectiveness of the river barriers in restricting

any potential for gene flow. I guess I

would weakly favor Option 2, to recognize 7 species (leucoptera, ochroptera, crepitans, napensis, viridis, obscura and dextralis). I can’t make myself go the extra mile in

splitting interjecta, which, from

what I can tell, isn’t even necessarily morphologically diagnosable.”

Comments from Robbins: “After reading the

proposal and Kevin’s comments, I support proposal 2, in recognizing seven

species of Psophia. Certainly, at a

minimum, proposal one should pass as the genetic data demonstrate that ochroptera must be transferred to crepitans if one is going to take the

narrow view that only three species should be recognized. Given the relatively little genetic

differentiation I appreciate how others might want to be conservative and

recognize only three species. Kevin is

correct that it may be a long time before pertinent vocal and display data are

obtained for these taxa. From what we

currently know, it does seem that the rivers, including the headwaters, are

acting as barriers to gene flow. Until

there are data to indicate otherwise, I lean more toward recognizing the seven

taxa outlined in proposal 2 as species.

Comments from Bret Whitney: “I see Ribas

et al, like most phylogeographic studies to date, as suffering from poor

sampling, especially for the two taxa east of the Xingu (= 2 for interjecta

and 1 for obscura), and uneven application of “results”. The

proposal says that Ribas et al. recovered “high support values for branches separating

taxa” except for “weaker" support value for crepitans and ochroptera.

I’d say several others are no or little better, especially where sampling

was poor (as it was for ochroptera = 2). Ribas et al (and,

implicitly, the proposal) don’t seem to have any reservations about

calling viridis, dextralis, and obscura monophyletic

species despite poor support, but do not mention similar, possibly

geographically linked structure within napensis (perhaps across the

Napo, a river known to separate a number of species-level taxa). Had

someone given a name to birds up in nw. Amazonas, Brazil, I imagine the

proposal would be recommending species-status for that, too. The

proposal, however, echoes a statement from Ribas et al to the effect of “the

phylogeny demonstrates clear differences between taxa butt little to no

structure within them…” The napensis example negates this assertion

and I don’t think they have enough of a sample of any taxa to make this

statement. Headwaters regions were woefully unsampled. Sampling was a little better in the

morphological study of Oppenheimer and Silveira, but it was also not robust.

“Another observation I have is two groups of ochroptera of

4-10 birds each that I have seen in Jaú National Park and near Barcelos that

had some individuals decidedly more orangish than others. This made me

wonder if the orange tint in the backs and remiges of these birds is real (=

genetically determined), or possibly an artifact of bathing constantly in

blackwater… something to at least think about, I suggest, in the same vein as

White-faced Whistling-Ducks showing variably orangish faces (but rarely

“white”) due to feeding habits. I can’t say I see orangish herons or egrets,

for example, more frequently in the Negro basin, but it does seem plausible

that pale-backed trumpeters bathing in dark-blackwater streams inside forest

could become heavily stained — and perhaps that is inevitable and to be

expected. Specimens of ochroptera are rare, and there are not many

available for analysis (Blake did have four males and a female and didn’t

mention any variation, but I would not expect him to unless it was dramatic).

“I would vote to accept proposal #1 and part of

#2, with napensis and ochroptera as subspecies of crepitans

(with a caveat on ochroptera as a valid taxon [tentatively

maintain it for now]); a monotypic leucoptera; and with the

split of viridis, dextralis, and obscura as species

because the analyses of Oppenheimer and Silveira, and Ribas et al., despite

very weak sampling, are congruent and mantle colors are quite different (in my

opinion); I think the split of the Dark-winged group represents an advancement

from where we are at present. I also have two recordings of adult,

captive obscura that are notably different from viridis and

dextralis, which are much more similar to each other — indicative

of differentiation, I would guess, but not enough on which to base judgments.

I would wait for more analysis of better sampling — morphological,

vocal, and genetic — of all taxa and putative populations before moving

for further revision; I do not see compelling reason(s) for doing more than

this at the moment. It certainly appears that interjecta is

individual variation, and we do not know whether overlooked cantatrix

Boeck 1884 from Beni represents an additional taxon or not; no sample from that

region was included.

“Some final thoughts — Would it not be possible to

include most or all of the specimens sampled by Oppenheimer and Silveira in

molecular analysis? It seems to me that most of them would have

sufficient material in their feet to permit extraction of tissue. I think

it would be especially wise to analyze all of the type specimens and a few

selected others, at least, to try to clear up some lingering doubts (that I

have, at least) about their provenance. Specifically,

Spix’s two leucoptera were labeled from the Rio Negro, but Hellmayr

decided they had to have come from south of the Amazon and west of the Madeira,

so fixed the type locality “left bank of the Rio Madeira”. He may be

correct in imagining that Spix obtained the specimens from villagers who had

them as pets, and they may well have originated west of the Madeira, but this

should be checked. Trumpeters are exceptionally fine pets and are traded

and kept by people all over the Amazon. I think it probable that the type

of P. viridis, from Parintins in the extreme lower part of the

Madeira-Tapajós interfluvium on the largest island of the Tupinambarana region,

was a pet that had been taken elsewhere; I doubt that trumpeters occur

naturally around Parintins. This should also be investigated genetically,

along with interviews of hunters and other locals on the island, who will

definitely know if trumpeters are in the forests there, or not.

Oppenheimer and Silveira cited a single specimen of viridis (MNRJ

9645) from “Machado, Mato Grosso”, an indeterminate locality.

It was the only example among their sample of 24 viridis that

had aberrant mantle coloration (two characters), and it was the only specimen

from Mato Grosso. They attributed the differences to individual variation

because another specimen “collected 70 km of this specimen (MZUSP 76728)

is typical…” Oppenheimer and Silveira did not indicate how they determined the

location of “Machado, MT” and did not map any Mato Grosso localities for viridis

(their figure 4). It would be desirable to analyze this interesting

specimen genetically in an attempt to understand something more about it.”

Comments

from Jaramillo: “YES on 1, and part of 2. Hmm, a problematic

one, but I find Bret’s comments valuable and convincing. Keep napensis and ochroptera as part of crepitans.

This moves us along, taking to consideration the new data we have, but

conservative on the parts that are still missing from this analysis.”

Comments

from Stotz: “YES to part

1. Currently I am unwilling to split up viridis based on current data.”

Comments from Remsen: “YES

on 1, following from Bret’s comments and waiting for additional data and a

proposal that would allow accepting of the part of 2 for which data are solid.”

Comments from Pérez-Emán: “YES

to Part 1. Nodal support grouping ochroptera

and crepitans has the weakest support

indicating that these three taxa are included in a polytomy. Besides, in the supplementary material you can

find the nuclear tree and there is a haplotype shared by both crepitans and napensis. This might be

ancestral polymorphism but it could also be gene flow. I think it is better to

be conservative until more data are available.”