Proposal (616) to South

American Classification Committee

Split Cacicus leucoramphus from Cacicus chrysonotus

The paper by Alexis F.L.A. Powell, F. Keith Barker, Scott M. Lanyon, Kevin J.

Burns, John Klicka, Irby J. Lovette (2013 “2014”) A comprehensive species-level

molecular phylogeny of the New World blackbirds (Icteridae) Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 71 (Dec.13): 94-112 offers

radically new insights into the phylogeny of all four subfamilies included in

the Icteridae: Sturnellinae: Meadowlarks; Cacicinae: Caciques and Oropendolas;

Icterinae: Orioles; Agelaiinae: Blackbirds, Cowbirds and Grackles.

To quote from their abstract: “Using mitochondrial gene sequences from all ~108 currently recognized

species 7 and six additional distinct lineages, together with strategic

sampling of four nuclear loci and 8 whole mitochondrial genomes, we were able

to resolve most relationships with high confidence. Our phylogeny is consistent with the

strongly-supported results of past studies, but it also contains many novel

inferences of relationship, including unexpected placement of some newly

sampled taxa, resolution of relationships among major clades within Icteridae,

and resolution of genus-level relationships within the largest of those clades,

the grackles and allies. “

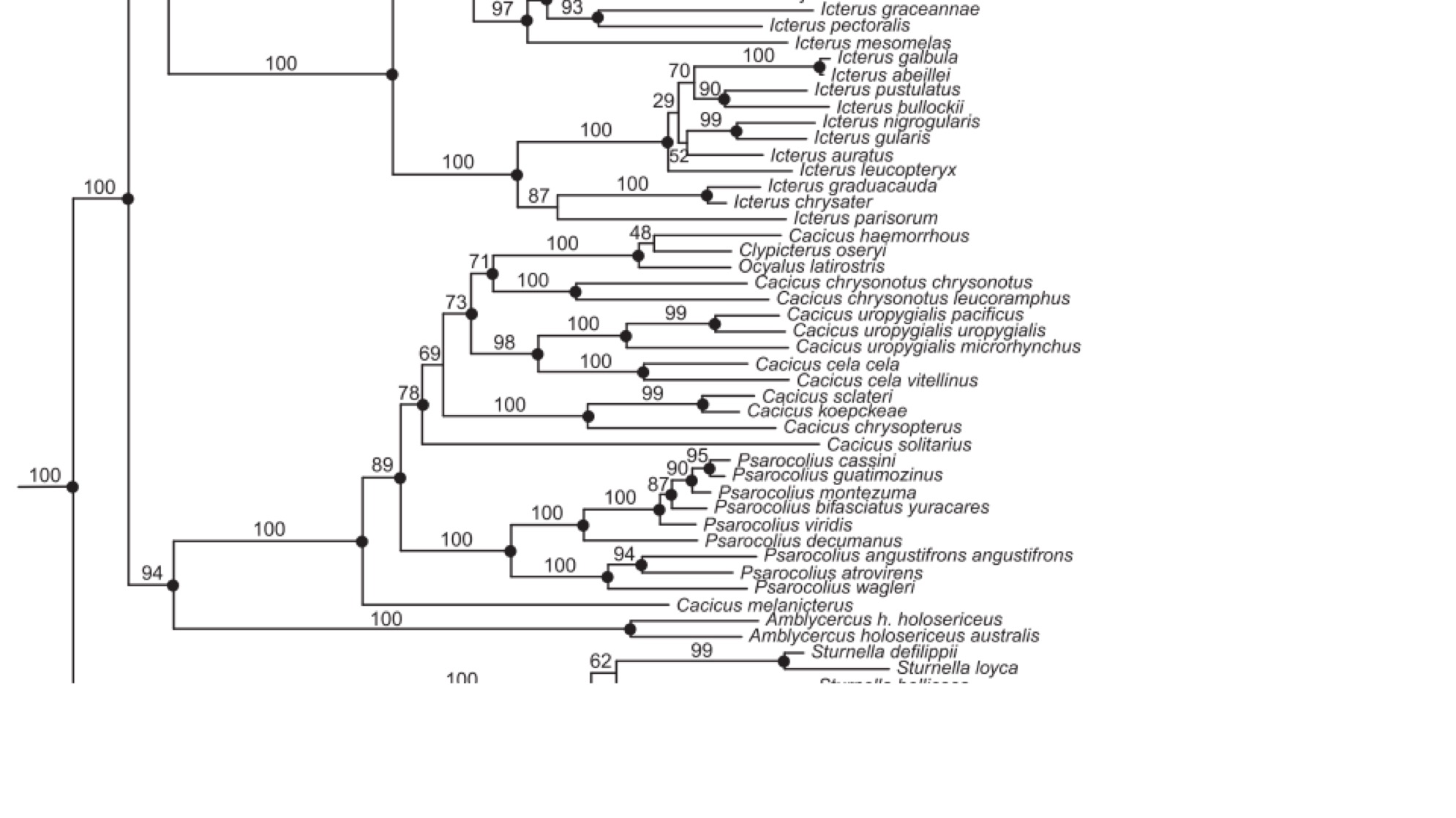

Below

I have inserted part of Figure 4 from their paper focusing of the

Cacicinae. The node uniting Cacicus chrysonotus and Cacicus leucoramphus is the second

deepest of the all of the species nodes in the Cacicinae. It is much deeper

than the node joining Cacicus sclateri

and Cacicus koepckeae and marginally

deeper than the node joining the two species just mentioned and Cacicus chrysopterus. It is also much deeper than the node joining Cacicus haemorrhous and Cacicus (was Ocyalus) latirostris and Cacicus (was Clypicterus) oseryi.

The

range of Cacicus leucoramphus

(northwest Venezuela to Ecuador) is distinct from that Cacicus chrysonotus pacificus (north Peru) and Cacicus chrysonotus chrysonotus of south Peru and north Bolivia.

Accordingly,

I propose that Cacicus leucoramphus.be

recognised as a species distinct form Cacicus

chrysonotus.

References:

Alexis F.L.A. Powell, F. Keith Barker, Scott M. Lanyon, Kevin J.

Burns, John Klicka, Irby J. Lovette (2013 “2014”) A comprehensive species-level

molecular phylogeny of the New World blackbirds (Icteridae) Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 71 (Dec.13): 94-112

John Penhallurick

______________________________________________________________________________

Comments

from Remsen: “NO. I appreciate the point that these two

differ in the same ways that C. sclateri

and C. koepckeae do in terms of

plumage but are roughly 3X more differentiated at the neutral loci

sampled. However, the design of this

study is inadequate for addressing differences at this level of taxonomy

because the two samples of leucoramphus

were taken from N. Ecuador (Imbabura), roughly 1800 km from the nearest

population of chrysonotus in southern

Peru. Not only would

isolation-by-distance come into play dramatically here, but those 1800 km cross

multiple major biogeographic boundaries, especially the Marañon, that would

likely create strong genetic subdivisions in any montane cloud-forest

bird. To use genetic data to address

species limits in these allopatric taxa, sampling would have to be directed at

the potential contact zone in southern Peru.

Hellmayr (1938, Catalogue of Birds of the Americas) noted that there are

plumage hints of possible gene flow between these two. [The Bond (1953) reference in our footnote

also evidently mentions this also but I can’t find my copy to check.] Note also that Powell et al., almost

certainly aware of the limitations of their data with respect to species limits

in these taxa, did not mention it in their discussion of classification and

treat the two as subspecies in their tree.

There is no relevant evidence in Powell et al. that chrysonotus and leucoramphus

should be treated as separate species.”

Comments

from Cadena: “NO. Sure,

genetic divergence is strong, but this may well reflect variation within a

single biological species. Using genetic distance as a yardstick to assess

species status is extremely problematic for various reasons (in brief, the

correlation between time and reproductive isolation is rather messy), and I see

no strong published evidence based on other traits (voices, behavior, plumage

variation) to support this proposed split.”

Comments

from Dan Lane: I agree with Van that the Powell et al.

(2013) paper can hardly be used to make taxonomic changes of this nature given

the limited sampling of individuals, the geographic distance between the

individuals sampled, and the genes used. But in addition to that, I have

further concerns about the above proposal. First, the suggestion that C.

leucoramphus be separate from C. c. “pacificus” (sic, should be peruvianus.

Pacificus is part of the C. uropygialis/microramphus group) and C.

c. chrysonotus is a novel taxonomy that has not been suggested anywhere

before that I can find, and as such would require considerably more background

to support. Cacicus leucoramphus, when split from C. chrysonotus,

has always included peruvianus as both have the yellow wing patches.

Assuming that this change to the organization of taxa within the complex was

unintentional, an additional issue arises as there are, as Van also stated,

specimens suggesting introgression between peruvianus and leucoramphus.

I myself have collected such an individual in the Mantaro valley, Junin, which

is near the supposed distributional break between peruvianus and leucoramphus.

A more densely sampled study including all three named taxa, including

populations such as that from the Mantaro valley, would be necessary to show

conclusively whether or not chrysonotus, peruvianus, and leucoramphus

are acting as good biological species or not. Until then, I would err on

the side of caution and maintain them as one species.”

Comments

from Stiles: “NO, for

the reasons advanced by Van and Daniel. An 1800 km gap between two small

samples makes the interpretation of the genetic differences equivocal. Without

statistically and geographically meaningful samples of genetics, plumages and

voice, the evidence for this split is insufficient to justify it.”

Comments from Nores: “YES. Although the data presented

here are not sufficient to justify the split, the two taxa are too different

(especially the lack of yellow on wings in chrysonotus).

Note that Schulenberg et al. (Birds of Peru) and Hilty (Birds of Venezuela)

treat chrysonotus and leucoramphus as separate species.”

Comments

from Zimmer: “NO, for

reasons already elucidated by Van, Daniel, Gary & Dan.”

Comments

from Jaramillo: “YES – this

is a poorly constructed proposal, but let’s not throw out the baby with the

bathwater here. In our Icteridae book we had some information on this problem.

First of all, Blake (1968), the Peter’s Checklist, actually considered chrysonotus separate from leucoramphus. To clarify as Dan has

done, there is no pacificus involved

in this issue (that is another issue), the three taxa fall into two groups with

peruvianus being the southern form of

leucoramphus. The two (chrysonotus with leucoramphus) were merged later based on intermediate looking

specimens, as Dan confirms. However, it was not clear to me who first came up

with the idea of the merger, it is too long since I looked into the issue, but

I do not think it is based on anything other than the few specimens of southern

birds with yellow feathers on the wing! The issue here is that chrysonotus with some yellow on the wing

occur way south in the range, in Bolivia. It appears to me that these birds

with some yellow on the shoulder are a variation that can pop out anywhere, not

intermediates. This is similar to C.

sclateri specimens that show some yellow on the rump both from Peru and

Ecuador! It is just something that shows up, perhaps a “throwback” to an

ancestral plumage state that is still in the bird’s genes?

“I would argue

that these two taxa were lumped based on poor analysis of the data, birds that

were thought to be intermediate are not, and I say we go back to Blake’s idea

and treat the two as separate species given that coloration, voice, and

genetics point to two sisters taxa that in all of those characteristics are as,

or more, different than other Cacique species we currently recognize.

At the time of

the book I had only heard the northern birds, and eventually in Bolivia I was

able to hear and see the southern birds. Calls are consistently different, and

call notes are important in flock cohesion in these social birds. Now we have

some recordings of their songs and they are extremely different to my ears:

Song of leucoramphus: http://www.xeno-canto.org/63204

Song of chrysonotus: http://www.xeno-canto.org/1996

“Furthermore my

limited personal experience with both of these birds is that the southern birds

(in Bolivia) are much shyer and skulking, difficult to see. While northern

birds (Ecuador) are much bolder and obvious. Of course that is a distance

apart, and there could be clines in behavior.

“Below are

specific parts from our book that deal with the problem:

… Ridgely and Tudor (1989) state that the vocalisations of the northern

leucoramphus group and the southern chrysonotus group to be similar. However,

recordings of the primary call (the ‘wheehk’ or ‘whak’) call appear to show a

difference. The southern birds sound higher pitched, metallic and quick; while

the northern birds are lower pitched, harsher and more powerful sounding. More

research needs to be done to elucidate how similar the vocalisations of

northern and southern forms are. ….. [we now have a lot more

information on xeno-canto to compare and confirm that these differences are

real and throughout the distribution]

GEOGRAPHIC VARIATION Three subspecies that fall into

two groups: leucoramphus [Northern Mountain Cacique] and chrysonotus [Southern

Mountain Cacique]. These two forms were listed as separate species in Blake

1968, but more recently the two have been considered conspecific (Ridgely and

Tudor 1989) mainly due to the presence of intermediate looking specimens.

Specimens of peruvianus from Auquimarca, Peru show black fringes to the yellow

wing coverts (Bond 1953). However, the vocalisations do not appear to be

similar, as has been stated (Ridgely and Tudor 1989). The two are certainly

good phylogenetic species, and perhaps even good biological species, more work

needs to be done before a decision as to the systematic placement can be made.

The

Northern Mountain Cacique is composed of two races. C .c. leucoramphus lives

from NW Venezuela, south along the E Colombian Andes to E Ecuador. It is

described above. C. c. peruvianus inhabits the east slope of the Andes from

Amazonas south to Junín. It is similar to leucoramphus, but has a heavier bill,

with the culmen more noticeably arched. The bluish base to the bill is less

extensive. As well, the concealed white collar is thinner in this form than in

leucoramphus.

The Southern Mountain

Cacique, C. c. chrysonotus, is found south of Junín, Peru to Cochabamba,

Bolivia. It lacks yellow on the wing coverts, however some individuals may show

one or two yellow covert feathers or small yellow tips to several coverts. This

is particularly true in the northern part of their range. However, some

Bolivian chrysonotus specimens, far from where intergradation could be

occurring, show yellow fringes to some of the wing coverts (Bond 1953).”

Comments from Dan Lane:

“Reading

the further responses in this proposal, I feel there are some clarifications of

the situation that I am in a position to make.

“First of all, in response to the comment above by Nores,

Birds of Peru (Schulenberg et al. 2007, 2010) did *not* separate C.

chrysonotus from leucoramphus at the species level, we maintained

them as conspecifics.

“Although I appreciate Alvaro’s comments on the subject, I

think they oversimplify the situation regarding this complex. Hand-picking two

recordings of what may or may not be homologous vocalizations from the broad

repertoire of an oscine with a linear distribution isn’t a very satisfying

comparison to me. Yes, the two recordings are both of songs, but are they the

same song types given under the same circumstances? Do we really even know what

kind of song types C. chrysonotus/leucoramphus has? Al’s comments from

Proposal 624 suggest that he believes there are several song types within any

given population of C. cela—an idea with which I agree—so why would this

congener be any different? And as we know is true in icterids, dialect

formation will be a serious issue to consider when dealing with geographic

variation among populations within this complex. Take a look at all the

recordings now available online:

http://www.xeno-canto.org/species/Cacicus-chrysonotus

http://www.xeno-canto.org/species/Cacicus-leucoramphus

“The Macaulay recordings include a selection which fills the

noticeable gap from central Peru (La Libertad, Huánuco, Pasco depts..) among

the Xeno-canto cuts. Listening to these cuts from San Martin to Bolivia, I hear

no obvious, discrete break in vocalization types between peruvianus and chrysonotus

to correspond to the turnover of plumage types. I have uploaded my own

recordings of the complex, including several from the Mantaro valley (both

sides), where birds with intermediate plumage are found (see a photo here of an

intermediate bird that was collected from a flock that I had recorded):

https://www.flickr.com/photos/8013969@N03/13547056163/

“I should point out that I used recordings of C. c.

peruvianus successfully to draw in the birds of intermediate plumage in

Junin.

“Checking LSU specimens, we have 13 C. chrysonotus

from Puno, Peru, and Bolivia. Of these, none show the yellow on the shoulder

visible in the Junin photo linked above. Colombian birds in our collection

appear smaller, with Bolivian birds appearing largest, but this could be

Bergman’s Rule at work, as the increase in size appears clinal. Again, I’m

really not impressed by the variation in voice among the recordings, especially

when one compares recordings along the length of the distribution of the

complex, rather than listening to extremes at distant points within it. The

lack of a clear change in voice when one compares recordings from the

Junin/Huancavelica/Cusco region of Peru, where the two 'species' turn over is

particularly unconvincing as evidence that there are indeed two species,

and added to this the presence of intermediate birds at this same area, it

almost appears as if this is one of the few cases among Andean birds where

allopatry does not stymie our application of the Biological Species Concept!

“Regardless, I think that I

would ‘throw the baby out’ with the present proposal. As it is worded, it does

a very poor job of clarifying the situation. A new proposal, with real

comparative data, would be needed (in my opinion) to make a strong case for the

separation of the complex into two species. Those data should involve a much

more directed study, including tissues from specimens from the turnover zone in

Pasco/Junin/Huancavelica/Cusco, as well as from all along the distribution of

the complex, as this is really necessary to make further sense of the situation

here.”

Comments from Robbins: “NO. After reading Dan Lane’s comments (especially

those in response to Alvaro’s remarks), I feel that much more information is

need in the region between the two extreme genetic samples.”

Comments from Pacheco: “NO. A partir das lúcidas colocações de Dan Lane, penso que

é muito prematuro decidir algo sem a existência de uma revisão consistente da

relação entre estes dois táxons.”