Proposal (639) to South American Classification Committee

Split

extralimital R. l. crepitans group from

Rallus longirostris

Synopsis: The following is the full proposal submitted to NACC on

revising species limits in the Rallus

longirostris/R. crepitans group,

sections of which are not directly relevant to SACC. The key issue is that the

taxon we call Clapper Rail, R.

longirostris, is not the sister species to the North American taxa

currently including in that species. This proposal has been approved and adopted

by NACC. The only taxa present in the

SACC area are members of the Rallus

longirostris group sensu stricto. A

YES vote means that the only change to the SACC list would be the change in

English name of more narrowly defined Rallus

longirostris to “Mangrove Rail”, and a NO vote means no change.

Description

of the Problem:

In

the most recent checklist (AOU 1998:131), there is a discussion of

hybridization between Rallus longirostris

and R. elegans in the eastern and

southern United States. There is a suggestion to merge the entire complex into

a superspecies, but phylogenetic and detailed hybridization studies of the

group have not been published until now (Maley 2012;

Maley and

Brumfield 2013). Taxonomy has always

been difficult in this group given plumage variation, morphologically distinct

allopatric populations, and uncertainty in the degree of hybridization between

populations currently in contact. For example, R. elegans of the eastern US are bright rufous ventrally and breed

in freshwater marshes, whereas R.

longirostris of the eastern US are duller ventrally and breed in saltmarshes.

Very similar allopatric birds of the southwestern US and northwestern Mexico

are bright rufous ventrally and breed primarily in saltmarshes, making their

classification into either species difficult (Olson 1997).

New

Information:

A

phylogenetic study using mitochondrial and nuclear markers found discordance

between genetic relationships and current classification (Maley and

Brumfield 2013). Rallus elegans, as currently recognized, is paraphyletic with

respect to R. longirostris. Genetic

lineages correspond roughly to geography instead of current species limits. The

R. l. obsoletus subspecies group found in California, Arizona, and

northwestern Mexico was discovered to be sister to R. e. tenuirostris of the highlands of Mexico instead of previously

suggested sister relationships to either R.

l. crepitans or R. e. elegans of

eastern North America (Hellmayr and

Conover 1942; Ripley 1977; Olson 1997). Additionally, the

lineages of the R. l. crepitans group

and R. e. elegans, which are known to

hybridize in eastern North America (Olson 1997), are in the same clade (Maley and

Brumfield 2013). This pattern of

hybridization apparently also occurs on Cuba (Olson 1997) between members of these same two lineages (Maley and

Brumfield 2013). This clade also

includes birds from throughout the Caribbean (Fig. 1). Detailed investigations

of hybridization using morphological, ecological, and genetic (mitochondrial

and nuclear) characters in Louisiana reveal that strong selection against

hybrids is likely preventing the fusion of these lineages (Maley 2012). Members

of the nominate R. l. longirostris

group of South America were found to be genetically distinct and sister to

Caribbean and eastern North American birds (Fig. 1B). In the study the authors

were unable to obtain samples of R. l.

longirostris, instead sampling two members of the group R. l. cypereti and R. l. phelpsi. The

following recommendations would remove R.

longirostris from the checklist, because members of this subspecies group

have not been documented in North America.

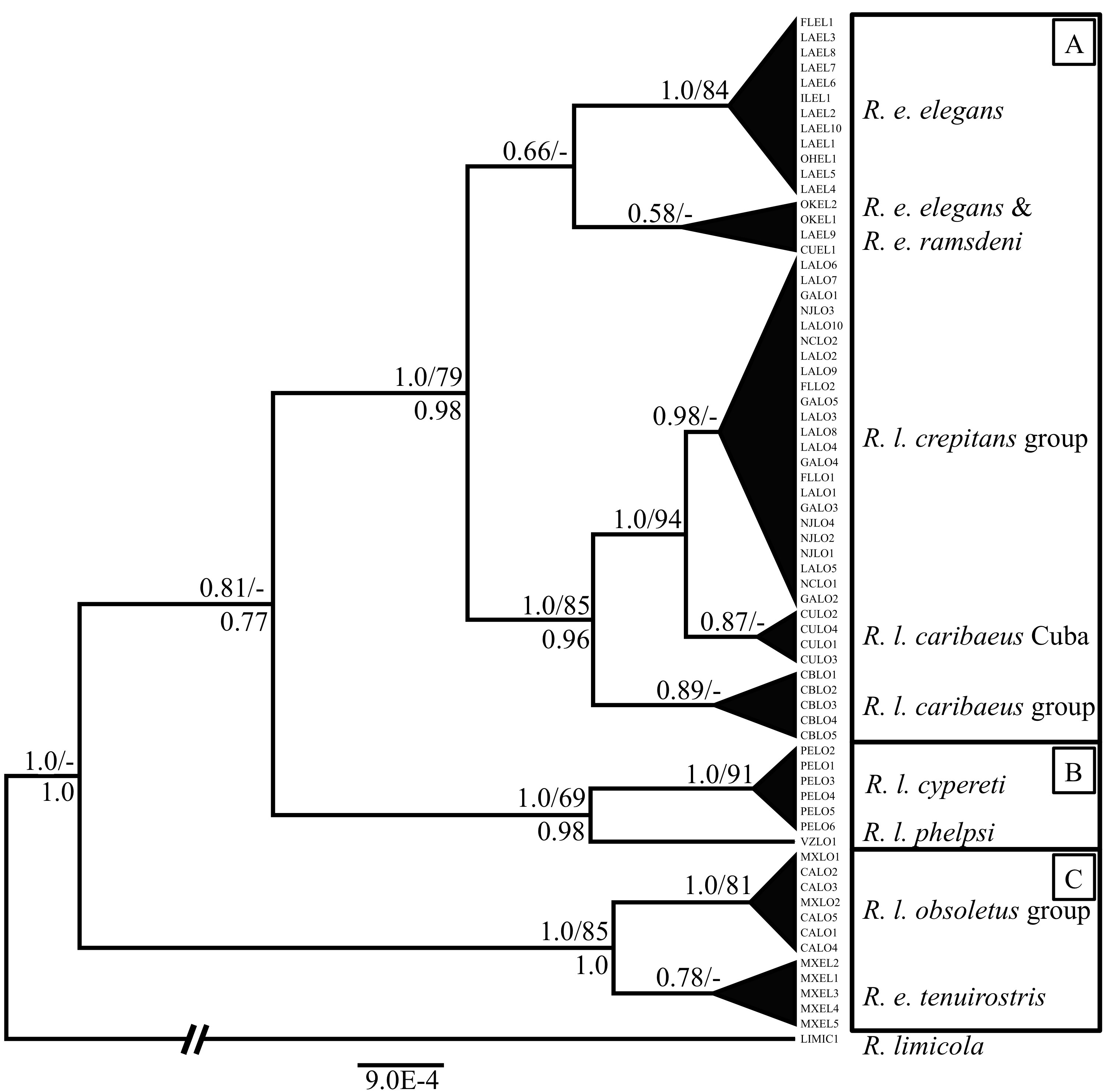

Figure

1. Maximum Clade Credibility gene tree of ND2 inferred in Beast (Drummond and

Rambaut 2007). The labels above

nodes are the posterior probability followed by the bootstrap support value (if

greater than 65) for that node. The labels below nodes are the posterior

probability for that node in the estimate of the species tree; this label is

not included if the value was below 0.95. Each of the three major clades is

outlined and labeled by geography, with clade A comprising eastern North

American and Caribbean birds, clade B comprising South American birds, and

clade C comprising birds of western North America, including Mexico.

Two

members of the complex are in extensive secondary contact in eastern North

America and Cuba, but have not fused despite hybridization (Olson 1997). The morphological and genetic characterization of the

hybrid zone in Louisiana (Maley 2012) found that it is very narrow (~ 4.2 km wide), with

selection against hybrids acting to prevent fusion. These data suggest there is

strong, albeit incomplete, reproductive isolation between these species in

Louisiana. There is no evidence of population genetic structure within R. longirostris in the eastern US, and

very little within R. elegans, so we

extrapolate these results for the entire distribution in the eastern and

southeastern US. Extending these results to the remaining taxa and considering

the differential level of morphological, ecological and genetic divergence

between previously identified subspecies groups, we conclude that at least five

species should be recognized in this complex. This treatment would be

consistent with recent genetic analyses of other members of the family showing

similar levels of divergence (Tavares et

al. 2010; Goodman et al. 2011). The most divergent

clade within the complex, according to mtDNA data, represents a pair of

subspecies groups from both currently recognized species (R. l. obsoletus group and R.

e. tenuirostris). This pair shares the same pattern observed in the birds

of eastern North America, where individuals of one group are relatively smaller

than those of the other and are found primarily in saltmarshes (R. l. obsoletus group), whereas the

other is relatively larger, brighter, and found in freshwater habitats (R. e. tenuirostris,

Olson 1997).

Recommendation:

We

propose species rank for five members of the complex described below. These

taxonomic recommendations are based primarily on two factors: 1) there is

strong but incomplete reproductive isolation between parapatric populations

based on hybrid zone analyses, 2) that each of the species represents a

morphologically and genetically distinct group within the complex that is at

least as distinct from other members of the complex as members that are

currently in contact but showing evidence of reproductive isolation.

We

propose recognizing as a species the nominate form R. longirostris Boddaert, 1783, plus the subspecies phelpsi Wetmore, 1941, margaritae Zimmer and Phelps, 1944, pelodramus Oberholser, 1937, cypereti Taczanowski, 1877, and crassirostris Lawrence, 1871. These

birds are relatively very small, dull-breasted, robust-billed, and restricted

to mangroves (Eddleman and

Conway 1998), which is why we

propose to give them the English name Mangrove Rail. This lineage is

morphologically, genetically, and vocally distinct from all other members of

the complex, and far more distinct from the rest of the complex than the

members that are currently in contact are from one another.

The

second species we propose is R. tenuirostris

Ridgway, 1874, which includes the

population of birds inhabiting the highland freshwater marshes of Mexico.

Individuals are large, very bright rufous ventrally, and have diffuse flank

banding (Meanley 1992). They are found almost entirely within the former Aztec

Empire and are not the only member of the complex found in Mexico; thus we

propose the English name Aztec Rail. They are distinct morphologically,

genetically, and ecologically from their closest relative, in that they breed

exclusively in freshwater marshes as opposed to saltmarshes, which is the same

reproductive isolating mechanism as found in other lineages within the complex.

The

third species we propose is R. obsoletus Ridgway,

1874, which includes the populations that occur along the Pacific Coast of

North America. This species would include the subspecies levipes Bangs, 1899, beldingi

Ridgway, 1882, yumanensis Dickey,

1923, rhizophorae Dickey, 1930, and nayaritensis McLellan, 1927. This group

is characterized by their relatively small body size (although larger than

South American birds), by a bright rufous breast, and by their occurrence

primarily in saltmarshes (Eddleman and

Conway 1998). Because Robert

Ridgway contributed a significant amount of work on the complex, including

describing R. l. obsoletus and R. l. beldingi, we propose the English

name Ridgway’s Rail in his honor. We propose species rank using a comparative

approach: because this lineage is as distinct morphologically, genetically, and

ecologically from its closest relative (R.

e. tenuirostris) as are other members of the complex in contact known to be

reproductively isolated.

The

fourth species in the complex we propose is R.

elegans Audubon, 1834, comprised of two subspecies, R. e. elegans and R. e.

ramsdeni Riley, 1913, while excluding R.

e. tenuirostris (as described above). We propose retention of King Rail as

the English common name. This species is distinct from its closest relatives

ecologically, morphologically, and genetically. Despite hybridization, they are

reproductively isolated from their closest relative in contact, members of the R. l. crepitans group, apparently due to

ecological differences (Maley 2012).

The

fifth species proposed is R. crepitans

Gmelin, 1789, comprised of the eastern North America group of R. l.

crepitans, including the subspecies waynei

Brewster, 1899, scotti Sennett, 1888,

insularum Brooks, 1920, and saturatus Ridgway, 1880, as well as the

birds of the Caribbean and Yucatan, including R. l. caribaeus Ridgway, 1880, pallidus Nelson, 1905, grossi Paynter, 1950, belizensis Oberholser, 1937, leucophaeus Todd, 1913, and coryi Maynard, 1887. These birds are

intermediate in size, and the breast spans a range of colors from very dull,

silvery-gray, to dull rufous. They breed in saltmarshes and salt-meadows of the

Atlantic and Gulf Coasts of North America, as well as mangroves in the Yucatan,

extreme southern Florida, Louisiana, and Texas, and throughout the Caribbean (Eddleman and

Conway 1998). We propose to retain

Clapper Rail as the English common name to avoid confusion. They are distinct

morphologically, genetically, and ecologically. Despite hybridization, they are

reproductively isolated from the other members of the complex they are in

contact with, R. e. elegans and R. e. ramsdeni (Maley 2012).

Literature

Cited:

James M. Maley

and Robb T. Brumfield, August 2013

======================================================

Comments

from Remsen: “YES I reviewed the paper at an early stage

and consider the authors’ taxonomic arrangement to be the one that matches best

the existing data. The elegans and crepitans groups have extensive, multiple contact zones, yet

hybridization is limited by apparent selection against hybrids; thus, they have

to be treated as separate species.

Ripley’s treatment (in his Rallidae monograph) of them as conspecific is

incorrect. Given that the other two

groups, including our R. longirostris

group, are successively more distantly related to the two for which we have a

test of sympatry, the logical taxonomic treatment is to consider them each also

as separate species.

“The Maley-Brumfield name Mangrove

Rail is a good one for reasons stated in their paper. Although the usual policy is to christen each

daughter species from a split with new names to avoid confusion,

phylogenetically this is not a case of splitting a species into two daughters:

in the case of R. crepitans and R. longirostris, they are not close to

being sister taxa, so Maley & Brumfield, followed by NACC, retained the

long-established “Clapper Rail” for the R.

crepitans group. What NACC calls extralimital

R. crepitans is actually irrelevant to SACC, but I mention this here

in case the issue is raised.”

Comments from Zimmer: “YES” to change the

English name of the more narrowly defined Rallus

longirostris to “Mangrove Rail”.

Given the data showing strong selection against hybrids from the various

contact zones in North America, the splits already adopted by the North

American committee appear justified. Because

our South American longirostris-group

is morphologically, genetically, vocally and ecologically distinct from all

other members in the complex, and these distinctions are greater than those

between sympatric/parapatric members of the complex, treatment of the South

American populations as a distinct species seems pretty straightforward. The proposed English name of “Mangrove Rail”

is perfect for these birds.”

Comments from Stiles: “YES. The only part of the proposal that

affects SACC is the English name Mangrove Rail, which is eminently reasonable.”

Comments

from Stotz: “YES. This split is clear. The North American committee spent way too

much time thinking about English names on this one and came up with Mangrove

Rail for the more limited longirostris. I think Mangrove Rail is a good name and so

favor the split and the English name.”