Proposal

(677) to South American Classification Committee

Recognize Systellura longirostris ruficervix,

Systellura longirostris roraimae, and Systellura longirostris decussata as

species

Effect on SACC: Elevate 3 subspecies within Systellura longirostris to species rank.

Background: Band-winged Nightjar Systellura

longirostris is a very widespread, polytypic species, distributed from

northern and Andean Venezuela south to southern Chile and Argentina, and in

eastern Brazil. Currently no fewer than nine taxa are recognized (Cleere 2010,

Dickinson and Remsen 2013). These taxa generally have a similar plumage

pattern, but differ in plumage saturation and size. A few subspecies, such as ruficervix (Cory 1918, Chapman 1923,

1926) and decussata (Cory 1918)

previously were recognized, based solely on plumage variation, as separate species.

Davis (1978) considered ruficervix to

be a species, but it is unclear how many taxa he vocally examined. Cleere

(1998) included all taxa within longirostris,

but at the time the vocalizations of only a few taxa were known. Later Cleere

(2010) recognized both roraimae and decussata as species, "based on

distinct vocalizations and range"; he included ruficervix in longirostris,

but also commented that "review of subspecies needed" across longirostris.

There is

no comprehensive quantitative survey of vocalizations in longirostris; for that matter, the songs of some taxa may not be

known (e.g. mochaensis, which is restricted to a small region in Chile). However, a nice summary of vocalizations of six taxa in this complex,

with sonograms and audio recordings, was prepared by Andrew Spencer; the

included taxa are longirostris, atripunctata, bifasciata, ruficervix, roraimae, and decussata": see xeno-canto.

More recently, the

situation was summarized by Crestol

(2015):

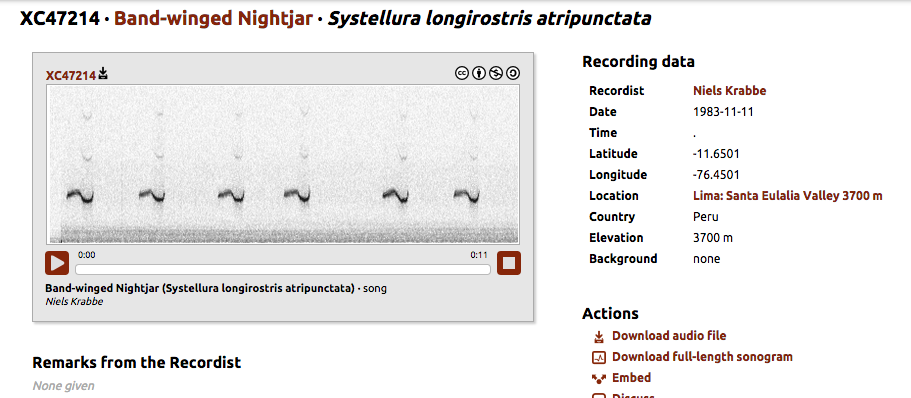

"Across much of its range, the song of Band-winged

Nightjar is a series of thin, high-pitched whistles. This song

variously is described as "a high thin seeeeerp or seeEEEeert

(emphasis varies), squeezed out, rising then down slurred in pitch" (Hilty

2003; subspecies ruficervix); as "a very high-pitched psee-yeet

or psee-ee-eeyt"

(Ridgely and Greenfield 2001b; subspecies ruficervix); as "a

series of high, thin slurred whistles: teeeEEEEuu" (Lane, in

Schulenberg et al. 2010; subspecies ruficervix and atripunctata);

as "a shrill but weak two-syllabled whistle, tse sweeet"

(Jaramillo 2003; subspecies bifasciata); and as "a

single, weak, very high-pitched plaintive whistle, repeated constantly: tseeooeet

... tseeooeet" (Belton 1984; subspecies longirostris).”

http://www.xeno-canto.org/47214

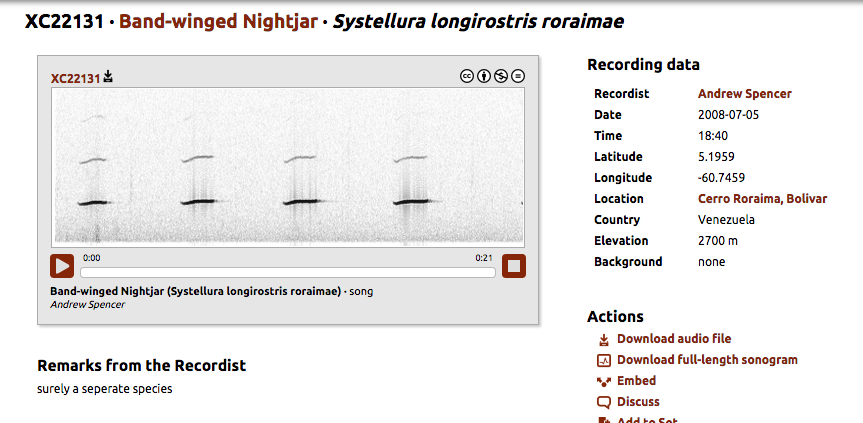

"The song of subspecies roraimae of

the tepuis is very different, and is a series of short, unmodulated, slightly

rising whistles.”

http://www.xeno-canto.org/22131

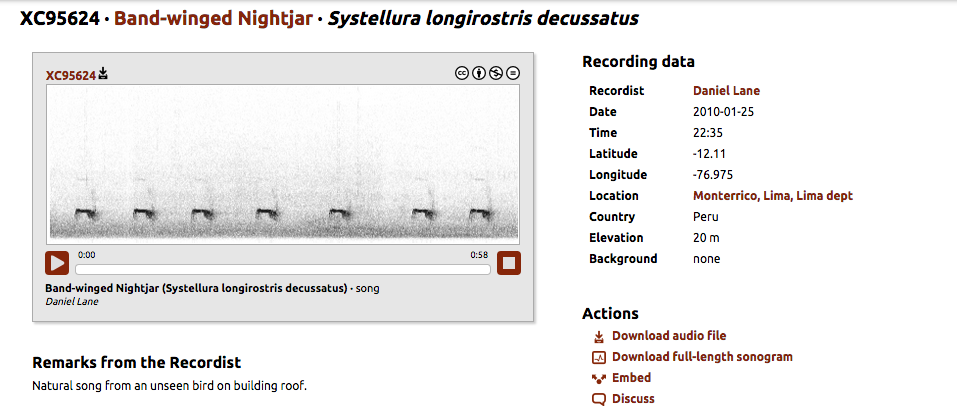

“The song of decussata, of the coastal

lowlands of western Peru and northern Chile, also is distinct: "a loud

series of cueeo notes, reminiscent of [the songs of Common]

Pauraque [Nyctidromus albicollis]

and Scrub

Nightjar [Nyctidromus anthonyi], but

more monosyllabic" (Lane, in Schulenberg et al. 2010)."

http://www.xeno-canto.org/95624

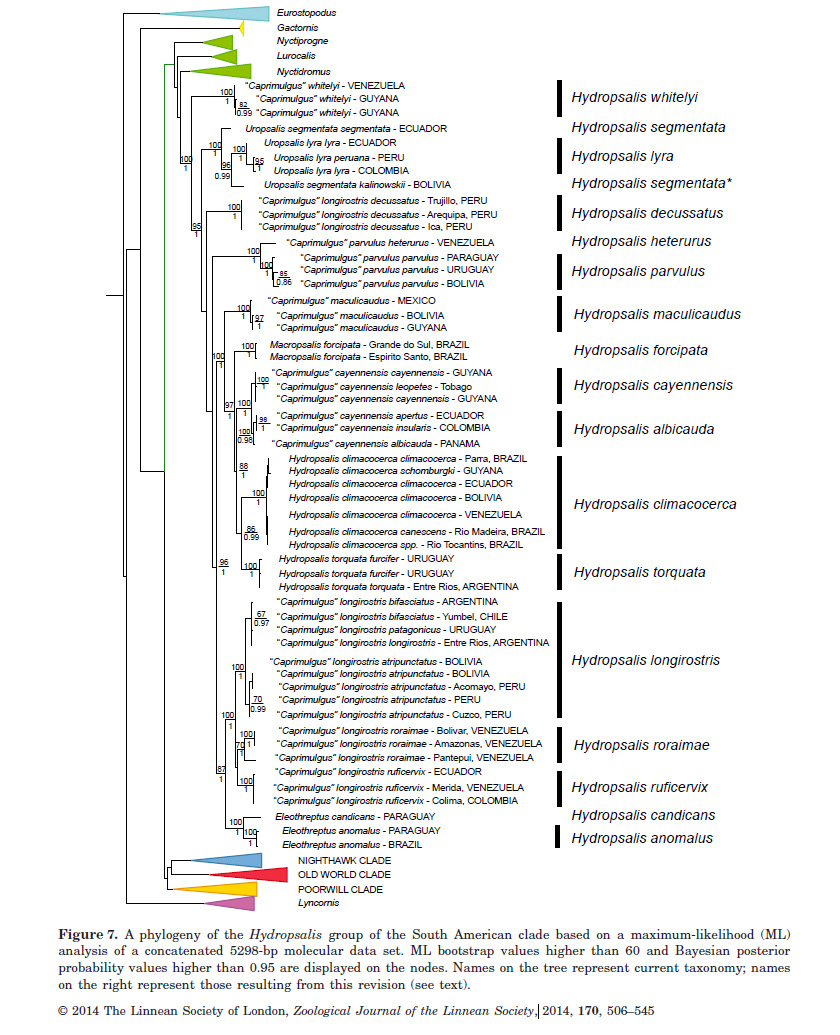

New Information: The current SACC taxonomy and nomenclature for

Caprimulgidae is based on Han et al. (2010), a phylogenetic analysis of DNA

sequence data (from cytochrome b, and nuclear c-myc and growth hormone genes).

Han et al. included a single example of polytypic longirostris (the subspecific identification was not provided in

the paper, but their sample represents ruficervix).

More recently Sigurdsson

and Cracraft (2014) conducted an independent phylogenetic analysis of New World

caprimulgids, again based on DNA sequence data (NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2,

cytochrome b, RAG-1, and nuclear intron 9 from the aconitase gene). Sigurdsson

and Cracraft also presented the first genetic data for multiple Band-winged

Nightjar taxa, with 18 samples that are identified as representing all but two of

its subspecies: mochaensis of Chile and pedrolimai of

northeastern Brazil.

As can be seen from their Figure 7, most taxa

of longirostris form a clade, which in turn has two subunits, one

composed of a group of taxa (atripunctatus, bifasciatus, longirostris,

and patagonicus) representing a wide swath of the geographic range of

the species, and another that pairs two taxa (ruficervix and roraimae)

that occur in montane areas (Andes and tepuis) of northern South America; these

two taxa are darkest in plumage.

A more surprising result

is that the traditional species longirostris is highly polyphyletic, as decussata

is distantly related to other taxa included in longirostris. Instead, it

is basal to the clade that includes the following genera recognized by SACC: Setopagis,

Hydropsalis, Macropsalis, Hydropsalis, Systellura, and Eleothreptus

(!).

Based on the above, the

following actions can be contemplated:

A)

recognize decussata as a species

B)

recognize both ruficervix and roraimae as separate species, based

on the genetic distinctions from the clade atripunctatus, bifasciatus,

longirostris, and patagonicus, and the vocal distinctions between ruficervix

and roraimae

Recommendation: Separation of decussata

as a species is mandatory, as the phylogeny presented by Sigurdsson and

Cracraft makes clear that it is not conspecific with the rest of the longirostris group. Based on the above

data sets, we also recommend a "yes" vote on Part B, for elevating

both ruficervix and roraimae to species level.

If these

pass, we need to think about English names. Cory (1918) and Cleere (2010) used

the name "Tschudi's" for decussata;

we have no objections to this name, and adopting it saves us the trouble of

thinking further about the issue. Cleere (2010) adopted the name "Tepui

Nightjar" for roraimae. which

again is a good name. Davis (1978) made the logical suggestion of "Rufous-naped

Nightjar" for ruficervix.

Obviously ruficervix is not the only

"rufous-naped" nightjar, but then, longirostris is not the only "band-winged" nightjar. So,

we propose that a "yes" vote for Parts A or B also constitutes assent

to our proposed English names, unless otherwise specified in comments with each

vote. If a committee member doesn't like our proposed names, then suggest

something else! If necessary, a separate vote can be held later on alternative

English names.

Finally,

note that decussata clearly cannot be

classified in the genus Systellura.

If SACC votes to recognize decussata

as a separate species, then a second proposal will be submitted on a generic

classification for decussata.

Literature Cited:

Belton, W. 1984. Birds of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Part 1.

Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 178: 369-636.

Chapman, F.M. 1923. Descriptions

of proposed new birds from Panama, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia.

American Museum Novitates number 67.

Chapman, F.M. 1929. Descriptions

of new birds from Mt. Roraima. American Museum Novitates number 341.

Cleere, N. 1998. Nightjars: a guide to

the nightjars, nighthawks, and their relatives. Yale University Press, New

Haven, Connecticut.

Cleere N.

2010. Nightjars, potoos,

frogmouths, oilbirds and owlet-nightjars of the world. Old Basing, UK: WILDGuides Ltd., Parr House.

Cory, C. B. 1918. Catalogue of birds of the

Americas. Part II, number 1. Field Museum of Natural History

Zoological Series volume 13, part 2, number 1.

Crestol, S. 2015. Band-winged

Nightjar (Systellura longirostris),

Neotropical Birds Online (T. S. Schulenberg, editor). Cornell Lab of

Ornithology, Ithaca, New York.

Davis, LI. 1978. Acoustic evidence of relationships in

Caprimulginae. Pan American Studies 1: 22-57.

Dickinson, E.C., and J.V. Remsen, Jr.

(editors). 2013. The Howard and Moore complete checklist

of the birds of the world. Fourth edition. Volume 1. Non-passerines. Aves

Press, Eastbourne, United Kingdom.

Han,

K.-L., M.B. Robbins, and M.J. Braun. 2010. A multi-gene estimate of phylogeny

in the nightjars and nighthawks (Caprimulgidae). Molecular Phylogenetics and

Evolution 55: 443-453.

Hilty, S.L. 2003. Birds of Venezuela.

Second edition. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

Jaramillo, A. 2003. Birds of Chile.

Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

Ridgely, R.S., and P.J. Greenfield.

2001b. The birds of Ecuador: field guide. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New

York.

Schulenberg, T.S., D.F. Stotz, D.F.

Lane, J.P. O’Neill, and T.A. Parker III. 2010. Birds of Peru. Revised and

updated edition. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

Sigurdsson,

S. and J. Cracraft. 2014. Deciphering the

diversity and history of New World nightjars (Aves: Caprimulgidae) using

molecular phylogenetics. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 170:506–545.

Tom Schulenberg and Mark Robbins, July

2015

=========================================================

Comments

from Zimmer: “This

proposal seems to be split into two parts.

Part A) Recognize decussata

as a species: YES. On this, the genetic data are clear. Part B) Recognize both ruficervix and roraimae as separate species:

YES. Genetic differences support

splitting these two from the main clade that includes nominate longirostris, and vocal and range

considerations would support treating ruficervix

and roraimae as separate from one

another. It has long been suspected that

“Band-winged Nightjar” encompassed multiple species. Adopting this proposal would be a good start

toward resolving some of the confusion, and provide a framework for redirecting

focus on the status of some of the remaining taxa under the longirostris-umbrella. The proposed English names seem reasonable.”

Comments from Stiles:

“A)

YES. At the very least, decussatus is

clearly not a member of the clade containing the rest of longirostris.

“B) YES. Vocalizations and genetics support splitting S. roraimae and ruficervix from longirostris,

and this also implies that atripunctatus and

the other southern races will also constitute at least one other species,

assuming that the Argentina sample is not nominate longirostris (although here, I assume that vocal data plus more

thorough genetic sampling are needed

to clarify this group).”

Comments from Areta:

“A) YES. The situation with decussata is

different, as it is not part of the PRESUMED longirostris complex, and

it appears to have been sufficiently well sampled.

“B) “NO. The taxonomy of Systellura

longirostris has long been known to be problematic and inaccurate. However,

I see several problems in adopting the proposed taxonomy in Sigurdsson &

Cracraft (2014).

“1)

Nominate longirostris, atripunctatus, and bifasciatus/patagonicus

have distinctive vocalizations (as diagnostic as those of other taxa afforded

species rank in their proposed taxonomy). Lumping them under a single species

is not recommended if we are to split the others, as it would mean having an

internally inconsistent Systellura.

“2)

Their single sample of nominate longirostris from Entre Rios (Argentina)

is very likely a migratory bifasciatus/patagonicus and not a true longirostris.

I speculate this based on known winter migration of bifasciatus/patagonicus,

and the lack of confirmed records of nominate longirostris in Argentina.

Thus, strictly speaking, we do not know what longirostris is in terms of

phylogenetic placement. This being said, since I fear that nominate longirostris

was not sampled, we do not know if longirostris indeed deserves to be in

the genus Systellura (type species Stenopsis ruficervix).

“3)

Subspecific distinctions of patagonicus and bifasciatus are

contentious, and they might not even be diagnosable (but more work is needed on

this). So it is surprising to find subspecific identification attached to the

bird in Uruguay, which must also be a winter visitor.

“4)

We (Thomas Valqui, Chris Witt and I) have been working for some time on a paper

on this complex, analyzing more recordings of all taxa, and with a better

genetic sampling. At present, even when there is disperse data clearly

indicating that current species limits are wrong, there is not a careful and

thorough characterization of variation and discreteness of vocalizations of the

involved taxa. Thus, I'd rather postpone a decision until such a work is

published.

“5) I

must stress that if we make a decision on this proposal based on xeno-canto

recordings, then a cascade of other proposals without critical proper review

must pass too. We all know of several groups with erroneous taxonomy and could

put 'quick' proposals together compiling disperse data to support a different

taxonomic treatment. I am of the view that solid taxonomic works require

careful scrutiny and attention to detail. I thus do not feel comfortable with

deep taxonomic changes in nightjars when the goal of a paper was not to

evaluate species limits, when the rationale for subspecific identification of

taxa is not made clear, and when relevant natural history information is not

included in the arguments. The work by Sigurdsson & Cracraft (2014) is a

great contribution to our understanding of phylogenetic relationships in

nightjars. But I do not think it contains enough information to solve this

puzzle.

Comments from Remsen:

“A) YES, for reasons outlined by others.

B) NO – I am strongly persuaded by Nacho’s reasoning.”

Comments

from Pacheco: “A) YES,

in accordance with what has been presented.

B) NO. After

the careful arguments provided by Nacho, I prefer to wait for more evidence to

decide about the specific limits within that complex.”

Comments from Nores: “A: YES. B: YES, especially with the

vocal difference between ruficervix

and roraimae, which are together in a

separate clade.”

Comments

from Jaramillo: “A. YES.

The form decussata/decussatus is

clearly not part of this group, based on molecular data. It is also the most

vocally divergent. If this proposal does go through, I would NOT be happy with

Tschudi’s Nightjar. I would rather choose an ecological/habitat name. Is Desert

Nightjar taken in the Old World?.

“B. YES. Although this may be

piecemeal and incomplete based on Nacho’s comments, I think that it would be

best to make a decision on these two (ruficervix

and roraimae) now. We have the data,

and it looks good. I doubt that Nacho’s work will not agree in the separation

of these two forms. I am guessing that their work may consider more splits in

the longirostris/bifasciatus/atripunctatus

etc. groups. But that can happen later, and I don’t see that it impacts the

current decision. I agree with Nacho that the Sigurdsson & Cracraft paper

does not “contain enough information to solve this puzzle” but it does contain

enough to solve some of the puzzle. So I think a YES on part B of this proposal

is defensible. By the way, I am unsure

of where exactly mochaensis is found,

but assume that Chiloe Island is part of the distribution. These birds sound,

to my ears at least, just like birds from Central Chile. They also respond to

recordings of birds from Central Chile.”

Comments

from Stotz: “

A. decussatus YES

B. split ruficervix and roraimae

YES

“I understand

that this is not the final story on this complex, but it seems like recognizing

these is not really affected by the fact that there may still be further splits

to do within longirostris. There are other taxa where we have recognized

splits, while still having complexes that have not been fully worked out within

the unit. An example of that would be

the recognition of Tolmomyias traylori,

despite the fact that are almost certainly multiple species within T. sulphurescens.”

Comments from Cadena: “677A. YES. 677B. NO. These sonograms

do look different and songs sound rather distinct, but are they representative

of variation existing within each of the groups and consistent across

geography? I think we cannot tell until data are properly (i.e. quantitatively)

analyzed with careful geographic sampling and such analyses are published.

Also, although this does not matter much given the proposal, the proposal

states that the longirostris clade

has two “subunits” with one corresponding to the montane taxa ruficervix and roraimae, but I note there is no support for these two taxa forming

a clade.”