Proposal

(703) to South American Classification Committee

Elevate Steatornithidae and Nyctibiidae to rank

of Order

Note: A nearly identical version of this proposal

has now been approved unanimously by the North American Classification

Committee.

Synopsis: To maintain the

monophyly of our current Caprimulgiformes and Apodiformes, this would elevate

two families to the rank of Order: Steatornithiformes and Nyctibiiformes.

Background: Our current classification treats the

Caprimulgiformes as containing three families: Caprimulgidae (nightjars),

Nyctibiidae (potoos), and Steatornithidae (oilbird). Our Apodiformes contains two families:

Apodidae (swifts) and Trochilidae (hummingbirds). These two orders have long been regarded as

closely related. Traditional

classifications also place the Old World Podargidae (frogmouths) and

Aegothelidae (owlet-nightjars) in the Caprimulgiformes. Recent genetic data (e.g., Ericson et al.

2006, Hackett et al. 2008, Prum et al. 2015) are concordant in finding that the

latter is actually sister to Apodidae + Trochilidae, and also that these three

families are embedded in the Caprimulgiformes, thus making traditional

Caprimulgiformes paraphyletic with respect to Apodiformes.

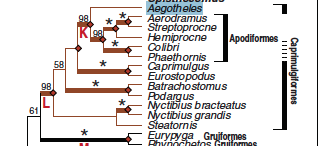

Here

is the relevant portion of the tree from Hackett et al. (2008):

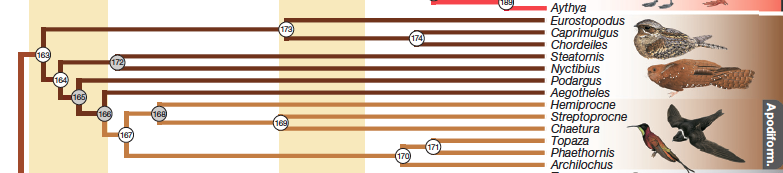

And

here is the relevant portion of the tree from Prum et al. (2015):

Cracraft

(2013) in Dickinson & Remsen (2013) [despite my objections] maintained the

monophyly of Caprimulgiformes by elimination of Apodiformes as an order and

inclusion of Trochilidae and Apodidae as families of the Caprimulgiformes. If this proposal is voted down, then

Cracraft’s solution is the simplest alternative option.

However,

an expanded Caprimulgiformes would include several lineages that are as old or

older than many other taxa ranked traditionally as orders; it would also be

spectacularly heterogeneous in terms of morphology – think of the profound

differences, for example, between a potoo and a hummingbird.

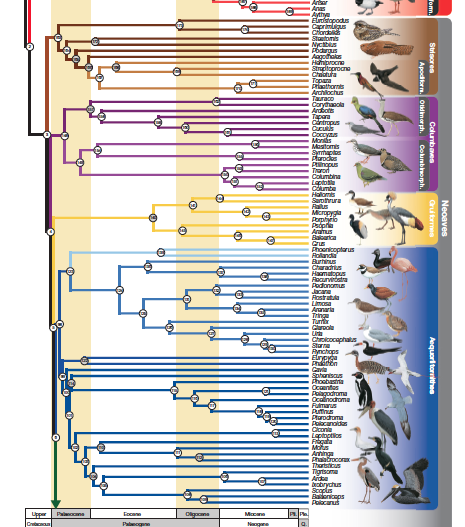

Here

is a broader view of the Prum et al. (2015) time-calibrated tree, with

geological time periods along the bottom; nodes are calibration points, which

are enumerated in the Supplementary material.

The resolution here is lousy; so if anyone needs a pdf, just let me

know:

With

all appropriate caveats concerning the uncertainty of the underlying data,

let’s use this figure as a gauge of relative lineage ages. If you draw an imaginary vertical line

through the tree in the very early Eocene at roughly 54 mya, the following

lineages are predicted to have been evolving separately at that point (with

taxa currently ranked as families by SACC marked in red):

1. Caprimulgidae

2. Steatornithidae

3. Nyctibiidae

4. Aegothelidae

5. traditional

Apodiformes (Trochilidae + Apodidae + Hemiprocnidae/inae)

6. Musophagiformes

7. Cuculiformes +

Otidiformes

8. Mesitornithiformes

9. Pterocliformes

10. Columbiformes

11. Gruiformes

12. Phoenicopteriformes

+ Podicipediformes

13. Charadriiformes

14. Eurypygiformes

15. Phaethontiformes

16. Gaviiformes

17. Sphenisciformes

18. Procellariiformes

19. Ciconiiformes

20. Suliformes

21. Threskiornithidae

22. our current

Pelecaniformes minus Threskiornithidae

Thus,

the lineages currently called Families in Caprimulgiformes are as old or older

than most lineages we label as Orders.

If

you zoom out to the full view of the tree in this figure, the following

lineages also intersect the line through the early Eocene:

23. all ratites plus tinamous

24. Galliformes

25. Anseriformes

26. Opisthocomiformes

27. Cathartiformes

28. Accipitriformes

29. Strigiformes

30. Coliiformes

31. Trogoniformes

32. Upupiformes + Bucerotiformes

33. Coraciiformes

34. Piciformes

35. Cariamiformes

36. Falconiformes

37. Psittaciformes

38. Passeriformes

Thus,

the signal is even stronger when one looks at the entire figure – lineages as

old as ca. 54 mya are consistently ranked in our classification as Orders or

even multiple Orders. Of the 5

exceptions, 4 are in traditional Caprimulgiformes. The fifth is the Threskiornithidae (for which

I will do a follow-up proposal to NACC).

I

emphasize that I recognize that the Prum et al. tree represents preliminary

analyses of new data, and that modifications are inevitable. Nonetheless, note that the topology and

chronology are generally consistent with other data, fossil (see Mayr tree

below) and genetic – in other words, this is not a radical overhaul of what we

know about relationships and how we portray them in hierarchical classification. Using Prum et al. (2015), however, at least

represents an objective approach to higher classification that differs from the

current data-free approach that is maintained by historical momentum.

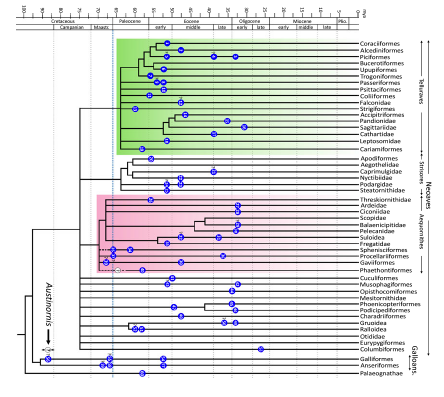

Below

is the figure from Mayr’s (2014) paper that maps the oldest fossils for crown

group birds. (I know the resolution

isn’t good – let me know if you need a pdf):

The

topology differs from that of Prum et al., but the lineage ages, reconstructed

on the basis of fossil data, are similar, namely all of the caprimulgiform

lineages are ancient, all projected to be evolving separately since the

Paleocene or early Eocene, i.e. as old or older as most taxa we rank as

orders.

So,

I propose the following higher-level classification of the group labeled as

Strisores by Mayr and Prum et al. (and based on the topology in Prum et al.

2015); brackets indicate extralimital taxa for which we do not have to endorse

the ranks explicitly:

Cohort/Superorder Strisores

Order Caprimulgiformes

Family

Caprimulgidae

Order Steatornithiformes

Family

Steatornithidae

Order Nyctibiiformes

Family

Nyctibiidae

[Order Podargiformes (extralimital)

Family Podargidae]

[Order Aegotheliformes (extralimital)

Family Aegothelidae]

Order

Apodiformes

[Family Hemiprocnidae

(extralimital)]

Family Apodidae

Family Trochilidae

For

those of you accustomed to thinking of the old Caprimulgiformes as consisting

of several similar family-level taxa of night birds, consider that the

phenotypic differences among these groups is masked somewhat by a degree of

convergent evolution on cryptic coloration.

Remove that, and these birds differ dramatically from one another. The echolocating Oilbird is the only

nocturnal frugivore in Aves and really bears no morphological resemblance to

any other bird. Likewise, the potoos

bear little resemblance to any other birds and have bill and eyelid morphology

found in no other group. The

owlet-frogmouths are just bizarre birds that don’t seem to resemble anything

else. Swifts and hummingbirds likewise

are unique groups in birds, and once you take away parallel extreme adaptations

for flight in terms of reduced feet and elongated wings, they share little in

terms of plumage and morphology – one could even make an argument based on

lineage age that they should also be treated as separate orders (in fact Pam

Rasmussen has a NACC proposal pending to treat them as orders). The morphological distinctiveness of each of

these groups is certainly related to the enormous amount of time since they

shared common ancestors.

I

recommend a YES vote on the proposal. A

NO would necessarily generate a proposal (by someone else) to treat them all in

the same order Caprimulgiformes (or perhaps some hybrid classification such as

including Aegothelidae and Trochilidae in Apodiformes, and potoos and oilbirds

in same order, each separate from Caprimulgiformes).

Literature Cited:

CRACRAFT, J. 2013. Avian higher-level

relationships and classification: nonpasseriforms. Pp. xxi-xliii in The Howard

and Moore Complete Checklist of the Birds of the World, 4th Edition, Vol. 1.

Non-passerines (E. C. Dickinson & J. V. Remsen, Jr., eds.). Aves Press,

Eastbourne, U.K.

DICKINSON, E. C., AND J. V. REMSEN, JR.

(eds.). 2013. The Howard and Moore

complete checklist of the birds of the World. Vol. 1. Non-passerines. Aves

Press, Eastbourne, U.K., 461 pp.

MAYR, G. 2014. The origins of crown group birds: molecules

and fossils. Palaeontology 57: 231–242.

PRUM, R. O., J. S. BERV, A. DORNBURG, D. J. FIELD, J. P.

TOWNSEND, E. M. LEMMON, AND A. R. LEMMON.

2015. A comprehensive phylogeny

of birds (Aves) using targeted next-generation DNA sequencing. Nature 526: 569-573.

Van Remsen, February

2016

==================================================================

Comments

from Claramunt: “A tentative NO. This is a difficult

decision. I’m inclined to choose the alternative of including Apodidae and

Trochilidae into Caprimulgiformes. Here are my reasons:

“1) Except for the

Aegothelidae-Apodidae-Trochilidae clade, relationships among the other families

are not well resolved. Hackett et al. (2008) recovered a

Nyctibiidae/Steatornithidae clade branching first, but with no strong support.

Osteological data suggested Steatornithidae alone branching first (Mayr 2010,

J. Zool. Syst. Evol. Res. 48:126-137). Finally Prum et al. (2015) show Caprimulgidae

branching first and the highest support (P =1) for all nodes in the main

analysis (figure 1), but a species-tree method resulted in a basal polytomy

(figure S3), so I don’t think that figure 1 is the final word on caprimulgiform

interrelationship. In any case the point is that intermediate solutions of 2 or

3 orders are not warranted, instead wee need to lump everything or split

everything, as in the current proposal.

“2) The proposal would result

in six orders where we had two before, and would create a nearly complete

redundancy between the Order and Family categories. Moreover, most of the

families already contain relatively few species in a single genus, and one, a

single species. Therefore, from pure (anonymous) taxonomic considerations, merging

Apodidae and Trochilidae into Caprimulgiformes seems a more conservative, less

radical, solution, and would result in a more balanced classification. So, are

there other considerations that make the conservative solution undesirable?

“3) I don’t see a signal of

Caprimulgiformes sensu lato being unusually old. First of all, the age of

Caprimulgiformes in Prum et al. is reasonable but the age of many other basal

nodes in the tree are underestimated, the result of a maximum age constraint at

the base of the tree that is too young. My own analyses (Claramunt &

Cracraft 2015: http://advances.sciencemag.org/content/1/11/e1501005)

show that Anseriformes and Galliformes (stem age: 72 Ma) are considerably older

than Caprimulgiformes (67 Ma). The later is indeed the oldest order within

Neoaves, but it is followed closely by Opisthocomiformes (66 Ma, just 1 million

year younger and with no chance of being split apart), Gruiformes (65 Ma),

Charadriiformes (65 Ma), and a long list of gradually younger orders. At the

level of families, the oldest nightbird family (in our tree) is Nyctibiidae (61

Ma), followed by Steatornithidae (60 Ma), which are younger than other four

families of Neoaves in the SACC region, Columbidae (64 Ma), Opisthocomidae

(66Ma), Cariamidae (63 Ma), Falconidae (62 Ma), and younger than other five

families outside the SACC region (Gaviidae, Musophagidae, Otididae, Coliidae,

Leptosomidae); all these older clades are both families and orders, so it could

be argued that Nyctibiidae and Steatornithidae also deserves to be orders. Old

families that are not orders at the same time are in the Galloanseres

(Anhimidae 69 Ma, Anatidae 68 Ma, Megapodiidae 58 Ma). Within Neoaves, old

families that are not orders are younger than the oldest nightbird families,

the oldest being Strigidae and Tytonidae at 56Ma, followed by Fregatidae,

Threskiornithidae and Meropidae at 54 Ma. If the 5 million years difference

enough to consider the nightbird families too old, given calibration

uncertainties and confidence intervals? Bottom-line, I see some signal of

nightbirds being old but I don't see them as unusually old, even if comparisons

are restricted to Neoaves.

“4) The inclusion of swifts

and hummingbirds into Caprimulgiformes would add a tremendous diversity in

number of species but in terms of broad ecophenotypic types, it would add just

two: diurnal aerial specialists (swifts, Caprimulgiformes already have

nocturnal aerial specialists), and the unique hummingbird nectarivore type.

With these additions, Caprimulgiformes join a group of megadiverse orders like

Gruiformes, Charadriiformes, and Passeriformes. Yet, an expanded

Caprimulgiformes (including swifts and hummingbirds) remain cohesive in overall

body proportions and internal anatomical details. All are medium to small sized

birds, have big heads, big eyes, long wings, short feet, and, except for the

nectarivore hummingbirds, big mouths. And cohesion is not just because of

superficial similarities; similarities in the internal anatomy revealed the

affinities between Apodiformes and Caprimulgiformes, and paraphyly of the later

in the firs place (Mayr 2002 J Ornithol 143:82–97). Of course each subclade has

its own characteristics, some of them unique among birds, but that is already

reflected in the classification at the level of Family.

“5) I admit that if swifts

would not exist, inclusion of hummingbirds and nightbirds in a single order

would be more difficult to endorse. But swifts do exist and somewhat fill the

gap between nightbirds and hummingbirds (or at least provide a “stepping

stone”). Actually, together they tell a very interesting story of a clade of

diurnal aerial specialists (swifts and hummingbirds) originating from a group

of nocturnal birds, and there are very interesting fossils documenting this

transition (Mayr 2002, Ksepka et al. 2013 Proc. Royal Soc. B 280).

“Therefore, so far I don't

see compelling reasons for not adopting the more conservative solution of

including all families into an expanded Caprimulgiformes, as in the Howard

& Moore list.

Comments

from Stiles: “YES. One

important point glossed over by Santiago is that the idea of a broad

Caprimulgiformes, implying that the Apodiformes evolved from nocturnal

ancestors, is that such an argument ignores the reorganization of the visual

system of nocturnal vs. diurnal birds. Evolution from nightbirds requires the

loss and reacquisition of visual pigments as well as major morphological

adjustments of the retina that seem to me to be highly improbable. Hence, I

favor continued recognition of Apodiformes at the ordinal level, as well as

recognition of Steatornithiformes and Nyctibiiformes, each of which have long

been evolving independently since the Eocene. As I see it, this does not conflict

with either the fossil evidence of Mayr or the Prum et al. calibrations (within

the error bars for same). The

“redundancy” of family and ordinal names in Steatornithiformes and

Nyctibiiformes simply recognizes that speciation has been limited in these

groups, at least since the Eocene; especially for Steatornithiformes, the

extremely specialized diet and reproductive biology seems a likely reason for

this.”

Comments

from Pacheco: “YES. The

two formulations (Van and Santiago) seem acceptable from the data, but I prefer

to an arrangement in order level more directly adjusted to the phenotype (when

possible) than a more comprehensive arrangement. I admit, however, that the

strongest argument in my vote is this: ‘all of the caprimulgiform lineages are

ancient (...) as old or older as most taxa we rank as orders’.”

Comments

from Jaramillo: “YES. This

is difficult, both suggested arrangements have problems as I see them. Santiago

has detailed many of the issues. But in the end, putting all of these birds together

in a single order I find more troubling.”

Comments

from Areta: “YES. This is largely a matter of

taste on how to better accommodate deep branches in the tree of life

nomenclaturally. Based on morphological and ecological differences, it makes more

sense to me to separate the bizarre Steatornithidae and Nyctibiidae (as well as

Podargidae and Aegothelidae) in different orders than to lump them with

Hemiprocnidae, Apodidae and Trochilidae, the latter of which (despite their

notable differences) form a more coherent grouping. There is always the

possibility of using the term Strisores to refer to all these families

conforming a diverse assortment of birds.”

Comments from Robbins: “YES. There are a lot of assumptions, from

problematic node support to even more questionable dating of these lineages,

that should cause one to pause. However,

if taken at face value, it seems reasonable to elevate Steatornithidae and

Nyctibiidae to ordinal level.

Nevertheless, I have no strong opinions on this and could easily be

convinced to adopt Cracraft’s convention.”

Comments from Zimmer: “YES. The idea of treating Tufted Coquette, Great

Potoo, Oilbird, Fork-tailed Palm-Swift and Long-trained Nightjar in the same

Order, is extremely unpalatable to me. I

understand the arguments for it, but I just can’t get there. I’d feel a lot better about elevating a few

families to ordinal level, even given some of the uncertainties of the

underlying data with respect to questions of lineage dating and node support.”