Proposal (717)

to South American

Classification Committee

Recognize the new genus Mazaria for “Synallaxis”

propinqua

“The best

definition of a genus seems to be one based on the honest admission of the

subjective nature of this unit…” (Mayr 1999:283)

Background: Synallaxis propinqua has been always included in the genus Synallaxis, classification that nobody

has questioned since the morphology and habits of this species seem typical of members

of this genus. However, in the comprehensive molecular phylogeny of Derryberry et al. (2011), propinqua appears as sister to Schoeniophylax

phryganophilus, and together they form the sister group of a clade

including Certhiaxis and other Synallaxis. Lack of statistical support

for the relevant nodes prevented making taxonomic rearrangements before the

surprising relationship could be confirmed.

New

Information:

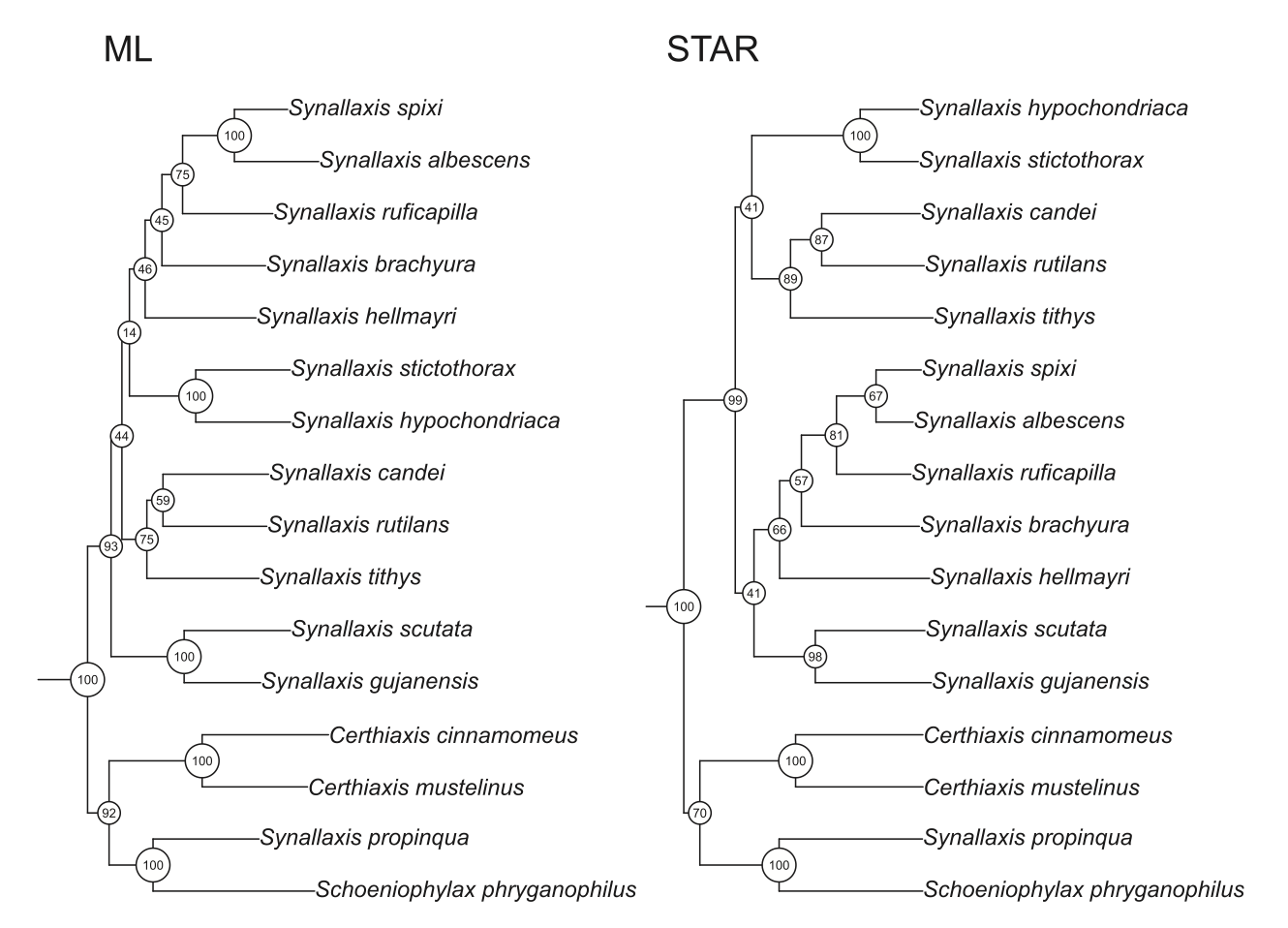

I recently revisited the problem with and enhanced molecular dataset including:

1) the mitochondrial ND2 gene (already analyzed by Derryberry et al. 2011), 2)

two introns from the Z chromosome (ACO1 and MUSK, analyzed together); 3)

introns 5-11 of the G3PDH gene (and intervening exonic sequences); and 4)

introns 5 and 7 of the beta fibrinogen gene FGB (Claramunt 2014).

When

analyzed separately, the four genomic regions independently showed a sister

relationship between propinqua and Schoeniophylax (bootstrap support:

G3PDH: 51, ND2: 86, Z-linked: 96, FGB: 100). There was less agreement regarding

the position of this pair of species within the larger clade, but G3PDh and

Z-linked genes showed propinqua and phryganophilus sister to Certhiaxis with strong bootstrap support

(94 and 99 respectively), whereas ND2 showed propinqua and phryganophilus sister

to Synallaxis but with low support

(73), and FGB did not resolve basal relationships. A sister relationship between the pair propinqua-phryganophilus and Certhiaxis

was also found when genes were analyzed jointly either by concatenation (ML

bootstrap: 92) and using a species-tree (STAR) method that accounts for

potential incomplete lineage sorting.

Given

these results, the classification needs to be changed. Among several options, I

opted for describing a new genus for propinqua,

which I named Mazaria, honoring our

dear Juan Mazar-Barnett.

Analysis

and Recommendation:

Although a sister relationship between propinqua

and phryganophilus was unexpected

given the phenotypic differences between these two birds and the similarities

between the former and other Synallaxis,

the molecular-phylogenetic evidence showing this relationship is overwhelming:

all four genomic regions independently corroborated the sister relationship

between propinqua and phryganophilus. Plumage similarities

between propinqua and other Synallaxis species must be ancestral

characteristics compared to the more-derived morphology of phryganophilus. However, propinqua

has more attenuated (pointed) rectrices compared to other Synallaxis and, regarding vocalizations, shares with phryganophilus the inclusion of

low-pitched guttural rattles as part of some of their vocalizations (something

that was pointed to me long ago by Brian O’Shea and Luciano Naka). The

divergence between propinqua and phryganophilus is a relatively old

event: between 7 and 10 million years ago, using biogeographic calibrations

(Derryberry et al. 2011), and between 4 and 12 million years ago using a

mitochondrial clock (Claramunt 2014). This explains the accumulation of

phenotypic differences between these sister species.

There

are three ways in which these relationships can be represented in a revised

classification:

A: Merge Certhiaxis and Schoeniophylax into an expanded Synallaxis.

B: Place propinqua in the genus Schoeniophylax.

C: Place propinqua in its own genus Mazaria, the option advocated in this

proposal.

Option

A is the least convenient, in my opinion. Synallaxis

is already very diverse and heterogeneous (it already includes the former

genera Siptornopsis and Gyalophylax, for example); inclusion of Certhiaxis and Schoeniophylax within Synallaxis

will increase this heterogeneity even more. Schoeniophylax

was previously merged within Synallaxis

by Vaurie (1980), but this treatment did not gain general acceptance. Moreover,

merging Certhiaxis into Synallaxis creates further

nomenclatorial problems as the Yellow-chinned Spinetail, S. cinnamomeus (Gmelin 1788), would become homonym with the

Stripe-breasted Spinetail S. cinnamomea

Lafresnaye 1843.

Option

B. Transferring propinqua from Synallaxis to Schoeniophylax is less disrupting than A regarding nomenclatorial

changes, although the White-bellied Spinetail would become Schoeniophylax propinquus, to match the masculine genus (David

& Gosselin 2002). The drawback of this option is that the resultant genus

would combine two species that are phenotypically very distinct, with no other

transitional species that fills the phenotypic gap between them. The resultant

genus would be difficult to characterize other than listing the sum of

characteristics of both species. Also note that these sister species are not

particularly closely related according to divergence time estimates. On the

other hand, note that the argument regarding phenotypic differences could be

turned around in support of Option B by arguing that the new taxonomy would

help showing a relationship that is otherwise difficult to recognize.

Option

C, is minimally disrupting other than introducing a new generic name. The

disadvantage of Option C is the creation of a monotypic genus that is not

informative regarding relationships and redundant in the sense that the genus Mazaria and the species Mazaria propinqua would contain exactly

the same taxon. On the other hand, monotypic taxa cannot be completely avoided

in general, and in this case, the monotypic genus would help represent the

phenotypic distinction of propinqua

in relation to its sister species and highlight that theses two species are not

particularly closely and have long history of independent evolution.

At

the end, I think that Option C would result in a classification that is more in

consonance with traditional conceptualizations of what an avian genus is (Mayr

1999) and therefore I recommend recognizing the new genus Mazaria for propinqua (a

YES on this proposal).

Literature Cited:

Claramunt, S. 2014. Phylogenetic

relationships among Synallaxini spinetails (Aves: Furnariidae) reveal a new

biogeographic pattern across the Amazon and Parana river basins. Molecular

Phylogenetics and Evolution 78:223–231.

David, N. & M. Gosselin 2002. The

grammatical gender of avian genera. Bull. Brit. Orn. Cl. 122: 257-282.

Derryberry, E. P., S. Claramunt, R. T.

Chesser, J. V. Remsen Jr., J. Cracraft, A. Aleixo, & R. T. Brumfield. 2011.

Lineage diversification and morphological evolution in a large-scale

continental radiation: the Neotropical ovenbirds and woodcreepers (Aves:

Furnariidae). Evolution 65(10):2973-2986.

Mayr, E. 1999. Systematics and the

origin of species from the viewpoint of a zoologist. Harvard University Press,

Cambridge, MA.

Vaurie, C., 1980. Taxonomy and

geographical distribution of the Furnariidae (Aves, Passeriformes). Bull. Am.

Mus. Nat. Hist. 166, 1–357.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Comments

from Remsen: “YES. I have been aware of this one for several

years and strongly concur with Santiago on all of this. The classification must be changed, and Option

C is clearly the best, in my view.”

Comments

from Areta: “YES. In

the most Mayrian sense of a genus, I endorse the placement of propinqua in

Mazaria. Vocally and phenotypically it does sound-look like a Schoeniophylax-Certhiaxis.

However, my subjective heart is pleased to see this new genus dedicated to the

memory of Juancito.”

Comments

from Bret Whitney: “I much

prefer Option B, in this case, for the primary reason Santiago recognized: one

genus for these two clarifies and highlights their sister relationship within

this huge family. That information would

be essentially obscured by assigning propinqua

a new genus, especially because I don’t fully agree that phryganophilus and propinqua

are “phenotypically very distinct”. Their

plumages and tail morphologies are fairly different, and the head/neck plumage

pattern of phryganophilus is

practically unique in the Furnariidae (approached, however, by Poecilurus, which got lumped into Synallaxis). Similarly, Siptornopsis is now considered a Synallaxis, together with sister stictothorax (= Option A) — but I’d certainly prefer to see the two

distinctive taxa in that clade in a genus apart (Siptornopsis), in the same manner as phryganophilus and propinqua

(propinquus) would be best, I think, comprising

Schoeniophylax.

“Phenotypic

distinctiveness of phryganophilus and

propinqua comes down a couple of notches when vocalizations are

considered. They uniquely share a harsh,

grating quality in songs and calls that is practically unique in the part of

the phylogeny presented in this proposal, and they both occasionally perform

fairly complex duets. Some of the others

in this part of the tree might be considered to give duets, in that the members

of the pair sometimes vocalize in tandem (e.g., Certhiaxis, also somewhat “harsh and grating"), but they are

not two-parted, synchronized vocalizations like those occasionally delivered by

pairs of Schoeniophylax. (I’ve never seen “Synallaxis" hypochondriaca

in life, and it’s been so long since I’ve seen stictothorax that I can’t

remember much about its vocalizations — so I don’t know about possible dueting

in that clade.)”

“The erection of a monotypic genus should

almost always be considered quite disruptive, just as is the lumping of

phenotypically distinctive clades/species traditionally considered separate

genera into related genera, always in the pursuit of avoiding paraphyly."

Comments from Stiles: “YES.

I definitely prefer diagnosable genera, even if monotypic; the only real

alternative, including both in Certhiaxis,

produces an undiagnosable soup.”

Comments from Pacheco:

“YES. I prefer C, the option that keeps a distinctive

genus for this taxon.”

Comments from Robbins:

“NO. I support option B, agreeing with

comments made by Bret. Moreover, the

continued movement for making anything that looks different and/or has a

relatively long branch in the tree as a monotypic genus is undermining the

purpose of nomenclature, i.e., effective communication and conveying

relationships.”

Comments

from Cadena: “NO. I largely agree with

Bret, and embracing the subjectivity noted by Mayr I subjectively prefer

classifications that are informative about relationships over the recognition

of monotypic genera except when dealing with real oddballs. Subjectively,

admittedly, I think this is not the case here.”

Comments

from Jaramillo: “YES –

Inclusion into Schoeniophylax is not

palatable to me, that is such a distinctive bird. Given that this pair is not

all that closely related to each other, I am ok with the creation of a

monotypic genus and happy that it is called Mazaria.”

Additional

comments from Remsen:

“I am a little surprised that this proposal met any opposition, so I am adding

some extra comments. Including propinqua in the same genus with Schoeniophylax phryganophilus creates an

indefensible morphological grouping in addition to the two lineages being

separated as long ago as many current genera.

In my opinion, these two species basically bear no resemblance to one

another in plumage or morphology (in contrast to the Siptornopsis group) other than sharing generalized synallaxines

features.

“As

for voice, here’s a Dan Lane recording of Schoeniophylax

phryganophilus: http://www.xeno-canto.org/149103. Here is a Lane recording of propinqua: http://www.xeno-canto.org/338635,

and one by Mitch Lysinger: http://www.xeno-canto.org/260647. Although I would agree with Bret that they

share some similarities with respect to other Synallaxis that in retrospect are consistent with a sister

relationship (length and pace), I also would not describe phryganophilus song as harsh and grating, but rather, in my

subjective opinion, amazingly rich and melodious, at least compared to any

other spinetail.”

Comments from Zimmer: “YES” on C. I’ve waffled back and forth on this one,

sharing some of the concerns raised by Bret, Mark and Daniel regarding erecting

a monotypic genus for a bird that is not that distinctive phenotypically or

vocally from other members of the larger clade.

But Schoeniophylax really is,

to my thinking, a unique bird, and lumping propinqua

into that genus results in a dilution of clarity regarding the uniqueness of Schoeniophylax that, in my opinion,

outweighs any informative gains of recognizing the sister status of the two

species by placing them in the same genus.

I think Van is spot-on in his comments regarding the alleged vocal

similarities of Schoeniophylax and propinqua. I too, find the song of Schoeniophylax to be “rich and melodious”, having a liquid,

gurgling tonal quality that is difficult to describe, and, which is unique

within the Synallaxines. Some of the

abbreviated contact-type or agonistic vocalizations of Schoeniophylax might be considered “harsh or grating” but no more

so than are the contact vocalizations and agonistic vocalizations of several

species of Synallaxis. To my ears, the harsh, grating vocalizations

of propinqua are much closer in

quality to those of Certhiaxis cinnamomea and C. species novum (from the Araguaia Basin) than they are to Schoeniophylax. And, to follow up on Bret’s musings regarding

Siptornopsis vocalizations, my

experience with the former Siptornopsis

species (stictothorax and hypochondriaca) is that both species

routinely duet, as does Certhiaxis. So neither the harsh, grating vocalizations

of propinqua, nor the fact that they

are given in duet, is enough in my mind to justify placing them with Schoeniophylax. That leaves morphological characters, and, as

Van points out, any morphological similarities between propinqua and Schoeniophylax

are really just generalized synallaxine features. Transferring propinqua to Schoeniophylax

would result in a tiny, amorphous genus that would defy any attempts to produce

a coherent diagnosis, solely to make clear that the two species are sister taxa.”