Proposal (753) to South

American Classification Committee:

Treat Poospiza whitii

as a separate species from P. nigrorufa

Effect

on South American CL:

This proposal would add Poospiza whitii to the SACC list, by splitting it from Poospiza nigrorufa.

Background: Three subspecies are

currently recognized in this complex: nigrorufa,

whitii, and wagneri, the latter of which has been considered doubtfully

distinct from whitii. Both nigrorufa and whitii were historically treated as full species until Hellmayr

(1938) lumped them by treating whitii as

the western subspecies of P. nigrorufa. Thereafter, nigrorufa and whitii were treated as a single geographically variable species but

by some authors as full species; see Jordan et al. (2017) for details.

Genetic data indicate that nigrorufa and whitii are well differentiated sister taxa with levels of mtDNA

divergence (ca. 2.5% for cyt-b and ND2) similar to those of other Poospizinae

sister species (Shultz and Burns 2013).

SACC proposal 79 failed to pass due to

lack of detailed published analyses, especially on vocal differences.

New

information:

Jordan et al. (2017) showed that

nigrorufa and whitii differ in 1)

plumage coloration and degree of dimorphism, 2) morphometric traits, 3)

habitat, distribution and ecological niche models, 4) vocal characters, and

that 5) in reciprocal playback experiments they ignore the other taxon while

answering strongly to their own vocalizations.

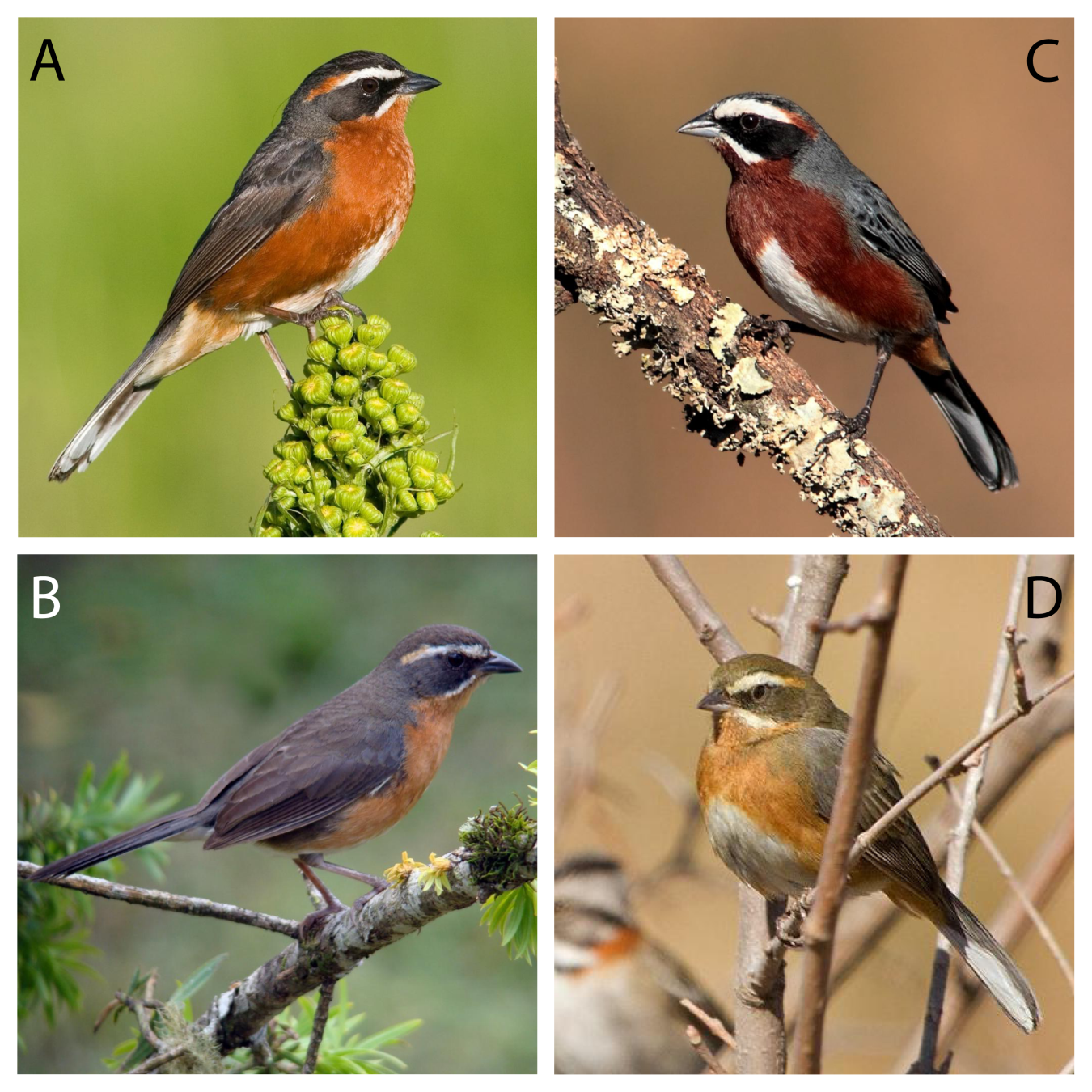

1) Plumage: In the slightly

dimorphic nigrorufa, males have tawny

rufous throat, breast and flanks, and are brownish grey with slate tinged upperparts (crown,

neck, back and rump), while females differ in the orange tinge of ventral parts

and in the more olivaceous upperparts. Sexes of nigrorufa are hard to distinguish both in field and museum

specimens. On the contrary, in the markedly dimorphic whitii, males have dark chestnut throat, breast and flanks, and

slate upperparts, while females exhibit tawny pale

orange throat, breast and flanks, and olivaceous

light-brown upper

parts (Fig. 1). In the field, females of whitii

exhibit paler ventral colors, and more olivaceous upperparts than both

sexes of nigrorufa. The key to

correct identification seems to be the extent of the white tip of the tail,

which is much greater in whitii than

in any sex of nigrorufa.

Jordan et al. (2017) also proposed that

the subspecies wagneri be treated as

a synonym of whitii because they were

unable to find any consistent plumage differences.

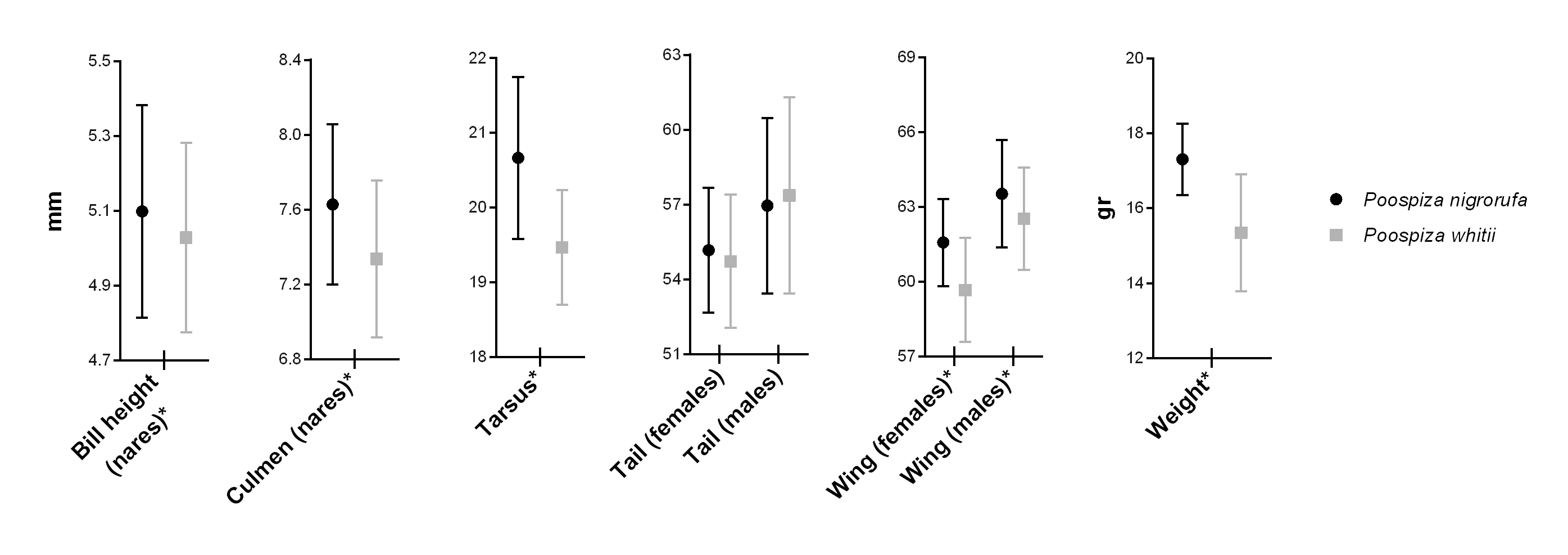

2) Morphometrics: Specimens of nigrorufa had significantly higher and

longer bill, longer tarsus and wings, and were~10% heavier than whitii (n=106 nigrorufa and n=91whitii).

Both species were sexually dimorphic, with males exhibiting longer wings and

tails than females. Within-sex comparisons between species show that nigrorufa has longer wings, but not

longer tails, than whitii (Fig. 2).

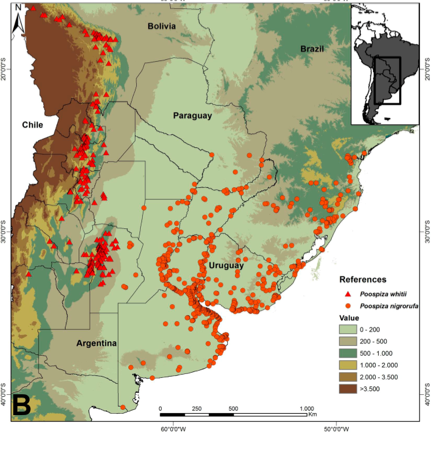

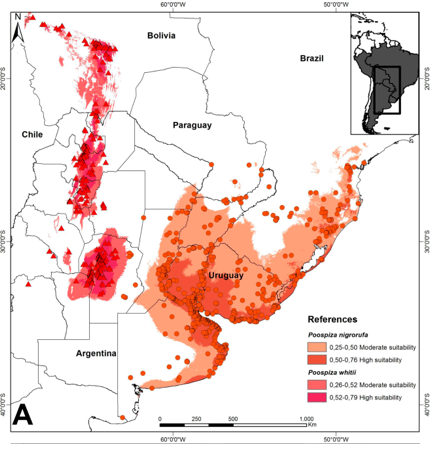

3) Habitat,

distribution and ecological niche models: Locality records (781 for nigrorufa and 322 for whitii) and models

of potential distribution indicate that ranges of both species are narrowly

allopatric, approaching closely in central Córdoba province (Argentina)

without overlapping (Fig. 3). P.

nigrorufa inhabits shrubby open areas in wetlands with reeds (Typha, Schoenioplectus) and bulrushes (Scirpus,

Rhynchospora) and grassy plains with

Pampas Grass (Cortaderia selloana),

whereas P. whitii inhabits closed to

semi-closed xerophytic to semi-humid scrub (Prosopis,

Geoffroea) and woodlands (Podocarpus, Alnus) far from wetlands. Finally, P. nigrorufa is generally a lowland species (except in southern

Brazil), whereas P. whitii is a

montane bird (Fig. 3).

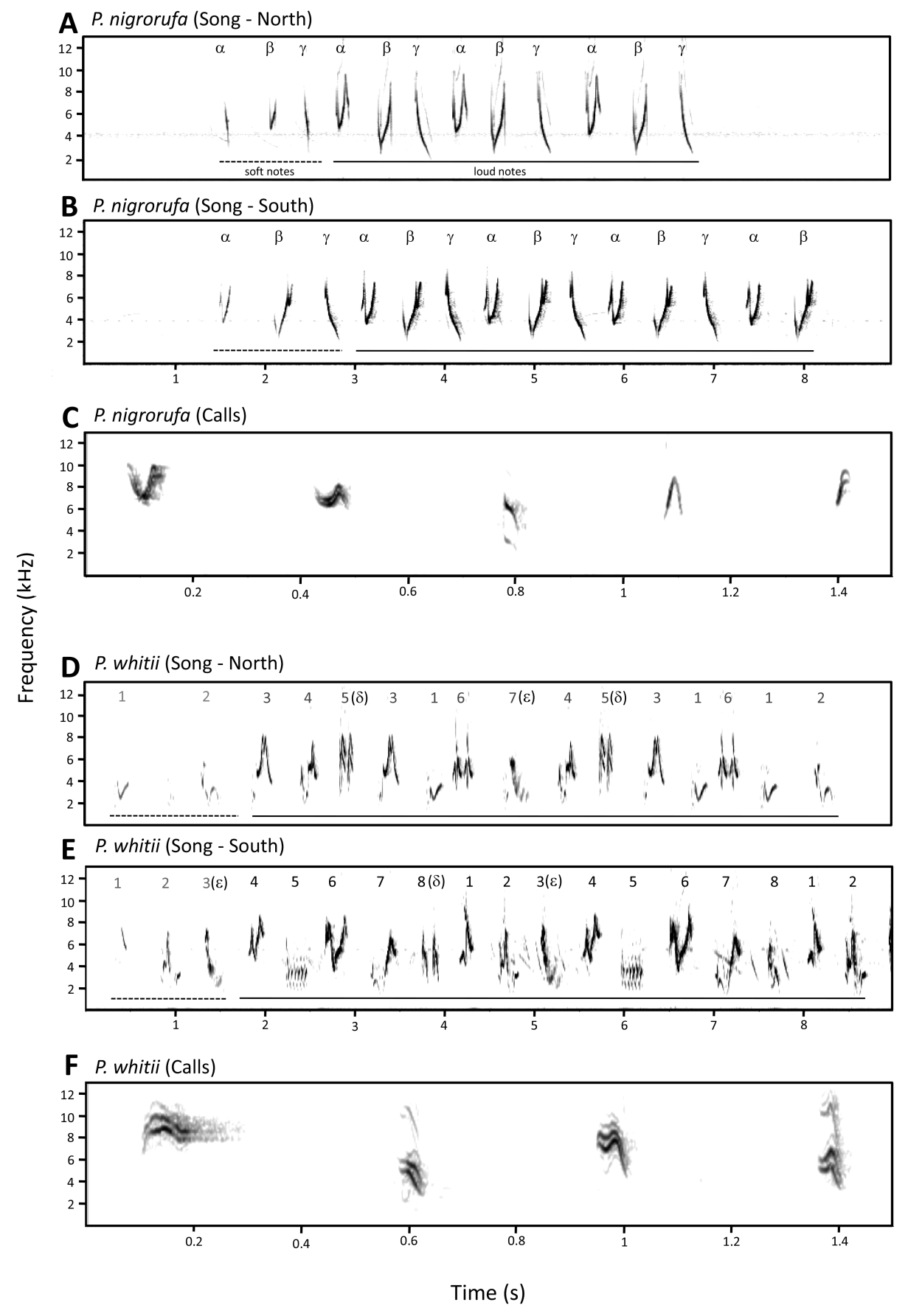

4)

Vocalizations: Songs

(108 individuals; nigrorufa n= 81, whitii n= 27) and calls (18 individuals;

nigrorufa n=14, whitii n= 4) differed dramatically (Fig. 4). The simple song of nigrorufa consists of one phrase with

three pure whistled notes, that is repeated a variable number of times. This

phrase is usually transliterated as pleased

to meet you in English, quem te

vestiu in Portuguese, or bichi-bichi

in Spanish. The general shape and order of the three notes of the song of nigrorufa are very consistent throughout the range of the species.

The complex song of whitii is composed of a succession of a variable number of notes

whose quality and order varies greatly from individual to individual. In stark

contrast to nigrorufa, the number of

notes performed by each analyzed individual of whitii varied between 8 and 12. A complete song is a rhythmic

series of single melodious notes, among which paired melodious notes and a few

trills are irregularly interspersed that might be represented as choo we, tip-tip, sweet peer, tweak, trrree, sweet peer.

The numerous calls of both species are

easily distinguished with the aid of spectrograms, but are virtually impossible

to distinguish in the field (Fig 4.).

5) Reciprocal playback

experiments:

20 reciprocal sandwich-playback experiments were performed in Argentina during

the breeding season. In all experiments, the ten males of nigrorufa and the ten males of whitii

responded aggressively to conspecific vocalizations by approaching to the

sound source and singing, while ignoring heterospecific ones, regardless of

stimulus order (n=15 conspecific and 15 heterospecific stimuli for each

species).

Recommendation: We recommend a YES

vote. All lines of evidence clearly show that nigrorufa and whitii belong

to different species under any species concept. This long overdue split is now

fully justified with solid integrative evidence, including behavioral responses

to mating cues.

Fig.1.

A: P. nigrorufa male (Ph: Sebastián

Preisz) B: P. nigrorufa female (Ph:

D. Lins). C: P. whitii male (Ph: G.

Núñez), D: P. whitii female (J. La

Grotteria).

Fig. 2.

Morphological measurements and weight of Poospiza

nigrorufa and Poospiza whitii

showing mean and standard deviation. Asterisks denote significant differences

with alpha=0.05

Fig.

3. Presence localities and potential distribution of Black-and-rufous

Warbling-Finch (Poospiza nigrorufa)

and Black-and-chestnut Warbling-Finch (Poospiza

whitii).

Fig. 4.

Spectrograms depicting songs (A, B, D, E) and calls (C, F) of adult males of

Black-and-rufous Warbling-Finch (Poospiza

nigrorufa) and Black-and-chestnut Warbling-Finch (Poospiza whitii). See Jordan et al. (2017) for further explanation

of symbols.

Literature cited

Hellmayr

(1938) Catalogue of birds of the Americas and adjacent islands. Field Museum of

Natural History Publications in Zoology 11, 1–662.

Shultz AJ

& Burns KJ (2013) Plumage evolution in relation

to light environment in a novel clade of Neotropical tanagers. Molecular

Phylogenetics and Evolution 66, 112–125. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2012.09.011

Jordan EA,

Areta JI & Holzmann I (2017) Mate recognition systems and species limits in

a warbling-finch complex (Poospiza

nigrorufa/whitii). Emu

https://doi.org/10.1080/01584197.2017.1360746

Emilio

A. Jordan and Juan I. Areta

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Comments

from Stiles:

"YES. The combination of genetic, morphological and ecological data

clearly shift the burden of proof to those favoring conspecifity of whitii."

Comments from Zimmer:

“YES. Multiple data sets confirm the

distinctiveness of these two taxa, and the playback experiments confirm the

importance of the vocal differences, which were noted by Ridgely and Tudor

(citing R. Straneck) as far back as 1989.”

Comments from Remsen:

“YES. The playback trials in particular

are convincing evidence that these taxa have diverged to the point that free

gene flow no longer likely.”

“If this passes, then I suppose we should use

the names in Ridgely & Tudor that are already fairly entrenched and

included in the proposal above. However,

this is one of those cases in which the usual policy of creating new names for

both daughters should have received serious consideration.”

Comments

from Claramunt:

“YES.

The evidence is solid, in my opinion.”

Comments from Cadena: “YES. The work by Jordan et

al. is an an excellent, integrative taxonomic study. I do not think that

morphometric analyses revealing differences in measures of central tendency are

very useful for species delimitation (especially for allopatric populations)

and I think that ecological differences as revealed by niche models are

especially revealing in cases unlike the present one where potential

distributions suggest there is potential for populations to come in geographic

contact yet they remain distinct (we described this with Andrés Cuervo in a

paper in 2010 but the idea has not gained much traction). Nonetheless, all the

evidence points in the same direction that there are two different species

here.”

Comments

from Pacheco:

“YES. The evidence gathered is convincingly strong.”

Comments

from Robbins:

“YES, for recognizing Poospiza whitii as

a species based on multiple data sets.”