Proposal (754) to South

American Classification Committee:

Elevate 13 taxa to species rank based on playback

experiments

A. Elevate Pseudocolaptes

johnsoni to species rank

B. Elevate Automolus

virgatus to species rank

C. Elevate Grallaria alticola

to species rank

D. Elevate Scytalopus

intermedius to species rank [superseded by SACC 858]

E. Elevate Ochthoeca

thoracica to species rank

F. Elevate Myadestes

venezuelensis to species rank

G. Elevate Pheugopedius

schulenbergi to species rank

H. Elevate Amazonian populations of Tunchiornis ochraceiceps to species rank

I. Elevate South American populations of Basileuterus culicivorus to species rank

J. Elevate Myiothlypis

chlorophrys to species rank

K. Elevate Myiothlypis

striaticeps to species rank

L. Elevate Atlapetes

tricolor crassus to species rank

M. Elevate Amazonian populations of Arremon aurantiirostris to species rank

A prelude to a set of 13 proposals: background

and methods from Freeman & Montgomery (2017):

Background:

Geographically isolated populations of birds

often differ in song. Because birds often choose mates based on their song,

song differentiation between isolated populations constitutes a behavioral

barrier to reproduction. If this barrier is judged to be sufficiently strong,

then isolated populations with divergent songs may merit classification as

distinct species under the biological species concept.

Methods:

We conducted playback experiments to measure

whether populations discriminated against song from a related, allopatric

population - these experiments that simulated secondary contact between

geographically isolated populations. Briefly, each experiment measured the behavioral

response of a territorial bird to two treatments: 1) song from the local

population (sympatric treatment) and 2) song from the allopatric population

(allopatric treatment). All territorial birds responded to sympatric song by

approaching the speaker (typically to within 5 m).

We defined song discrimination as instances in

which the territory owner(s) ignored allopatric song, defined as a failure to

approach within 15 m of the speaker in response to the allopatric treatment. We

calculated song discrimination for each taxon pair as the percentage of

territories that failed to approach the speaker in response to allopatric song.

For example, a song discrimination score of 0.8 indicates that 80% of

territorial birds (e.g. 8 out of 10) ignored allopatric song while

simultaneously actively defending a territory. We assume that song

discrimination is a proxy for premating reproductive isolation; that is, our

experiments provide insight into whether these populations would recognize each

other as conspecific and interbreed (or not) were they to come into contact

with one another. It is unknown what degree of song discrimination is “enough”

that song constitutes a strong enough premating barrier to reproduction that

allopatric populations merit classification as distinct biological species. To

provide a yardstick, we considered nine allopatric Neotropical taxon pairs that

were recently split (or have pending proposals to SACC) in part based off

differences in vocalizations. We found the average song discrimination in these

nine taxon pairs to be ~ 0.6 (60% of territorial birds ignored allopatric

song), and suggest that species limits deserve to be reconsidered when taxon

pairs currently classified as subspecies have song discrimination scores above

~ 0.6.

In most cases, we played songs of populations A

and B (where populations A and B comprise a taxon pair) to territorial birds of

population A. That is, in the majority of cases we asked whether population A

discriminated against song from population B but not the reverse. To date, we

have conducted reciprocal playback experiments for 23 taxon pairs (13 oscines

and 10 suboscines, see Table S2) in which we measured both discrimination of

population A to song from population B and also discrimination of population B to

song from population A and in which we conducted at least four experiments on

each population (n = 11.5 ± 3.8 playback experiments/population, range = 4 – 23, see

Table S2). Song discrimination in these reciprocal cases was highly correlated

(r = 0.88, t = 8.4, df = 21, p-value

< 0.0001, Figure 1). There were no examples with strongly asymmetric song

discrimination (e.g. population A discriminates against population B, but

population B does not discriminate against population A). We therefore assume

that unidirectional data accurately describes song discrimination within taxon

pairs in our database.

Please forgive the brevity of the following

proposals. I did not have time to give each proposal the detail it deserves;

nonetheless, I believe the “bare-bones” approach of these proposals provides

sufficient relevant information to consider re-evaluating species limits in the

following 14 cases.

Benjamin

Freeman, 15 September 2018

754A.

Elevate Pseudocolaptes johnsoni to

species rank

Effect

on SACC:

Elevate Pseudocolaptes johnsoni to

species rank (split from Central American Pseudocolaptes

lawrencii).

Background: Related populations

of Pseudocolaptes (tuftedcheeks)

occur in Central America (lawrencii)

and western Colombia and Ecuador (johnsoni).

These allopatric populations are currently classified as conspecific, but

differ in plumage and voice. Due to these differences in mate choice traits,

they have sometimes been considered to represent two distinct species (e.g.,

HBW).

New

data:

Freeman and Montgomery (2017) conducted playback experiments on 10 territories

of Central American lawrencii. They

found that 9 out of 10 territorial birds discriminated against song playback of

South American johnsoni

(discrimination = fail to approach within 15 m of the speaker. For canopy

species such as Pseudocolaptes, we

calculated distance to speaker in the horizontal plane. That is, a bird perched

high in the canopy but directly above the speaker would have a distance to

speaker of 0 m). Perhaps relevant is that these two populations differ in ND2

sequences (mtDNA) deposited on GenBank by 8.5% in uncorrected p-distance, which

suggests these two populations may have evolved strong postmating isolation as

well, although this is speculative.

Competing

proposals:

1)

NO

= Retain the status quo.

2)

YES

= Elevate Pseudocolaptes johnsoni to

species rank (split from Central American Pseudocolaptes

lawrencii).

Recommendation: Central American

birds respond strongly to lawrencii

song, but essentially ignore song from johnsoni.

This suggests that vocal differences constitute a strong premating barrier to

reproduction between these taxa. I therefore recommend treating johnsoni and lawrencii as distinct biological species. English names currently

in use are Pacific Tuftedcheek for johnsoni

and Buffy Tuftedcheek for lawrencii.

However, at present “Buffy Tuftedcheek” refers to johnsoni + lawrencii. I

am agnostic on English names for this (and every other) proposal.

Additional

material added by Peter Boesman:

Morphological

differences were summarized in del Hoyo & Collar (2016): “Until recently, normally considered conspecific with P. lawrencii,

but differs in its stronger rufous (less buff-tinged) mantle and back (ns[1]);

rich rufous vs grey-streaked cream-buff underparts (3); rufous-tan vs

grey-black outer vanes of primaries (2); wing-coverts dark grey-brown with

vague rufous edges vs blackish with strong rufous tips (2); shorter tail

(sample size too small, but evidence indicative; ns).”

Vocal differences were treated by Spencer (2011) and Boesman (2016), and summarized in del Hoyo & Collar (2017): “divergent

song, being a high-pitched (score 2) rattled series of notes, slowing into

stuttering and ending (always) with a characteristic high-pitched down-slurred

note (2), vs several well-spaced staccato notes followed by a trill, which

usually ascends in pitch and then descends while slowing in pace (1).”

Playback

response was evaluated in one direction. Both Spencer

(2011) and (more systematically) Freeman & Montgomery (2017) found no response

of lawrencii to playback other than its own taxon-specific voice.

Comparative genetic differences: data is available for the three groups GenBank, apparently a genetic

tree which includes the three groups has not been published yet.

See:

Boesman, P. (2016). Notes on the vocalizations of

Buffy Tuftedcheek (Pseudocolaptes lawrencii). HBW Alive Ornithological

Note 87. In: Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx

Edicions, Barcelona. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow-on.100087 https://static.birdsoftheworld.org/on87_buffy_tuftedcheek.pdf

Spencer, A. (2011). Variation in Tuftedcheek

vocalizations. https://www.xeno-canto.org/article/99

754B. Elevate Automolus virgatus to species rank

Effect

on SACC:

Elevate Automolus virgatus to species

rank (split from Amazonian Automolus

subulatus).

Background: Related populations

of Automolus woodhaunters occur west

of the Andes (virgatus group in

Central America and western Colombia and Ecuador), and east of the Andes (Amazon

basin; subulatus group). These

allopatric populations are currently classified as conspecific by SACC, but

differ markedly in voice, and somewhat in plumage. Due to these differences,

they have often been considered to represent two distinct species (e.g., HBW,

many field guides).

New

data:

Freeman and Montgomery (2017) conducted playback experiments on 12 territories

of virgatus group individuals (6 in

Costa Rica and 6 in western Ecuador). They found that 11 out of 12 territorial

birds discriminated against song playback of the Amazonian subulatus group (discrimination = fail to approach within 15 m of

the speaker).

Competing

proposals:

1)

NO

= Retain the status quo.

2)

YES

= Split Automolus virgatus from A. subulatus.

Recommendation: Central American and

Choco birds respond strongly to local song, but essentially ignore song from

Amazonian birds. This suggests that vocal differences constitute a strong

premating barrier to reproduction between these taxa. I therefore recommend

treating the virgatus group and the subulatus group as distinct biological

species. English names currently in use are Western Woodhaunter for the virgatus group, and Eastern Woodhaunter

and Amazonian Woodhaunter for the subulatus

group.

Additional

material added by Peter Boesman:

Data available in 2003 were summarized in proposal https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCprop40.htm.

Besides the main remark that no peer-reviewed paper

had been published, there was also some uncertainty about cordobae. Since then, no in-depth study has been

published, but the following can be noted:

Morphological

differences were summarized in del Hoyo & Collar (2016) after studying a series

of specimens: virgatus group has duskier

underparts , with pale flammulations more confined to upper breast (1) and

slightly darker chestnut tail (1).

Vocal

differences have been qualitatively described in a variety of sources, were treated

more quantitatively in Boesman (2016), and summarized in del Hoyo & Collar

(2017): “virgatus group has a highly divergent song:

a series of evenly spaced identical short staccato notes

“keek..keek..keek..keek” vs a series of just a few (usually 2-3) downslurred

notes, often (perhaps when excited) followed by a low-pitched rattle, hence

more (ns 1) and much shorter notes (3) with a double peak frequency (2).”

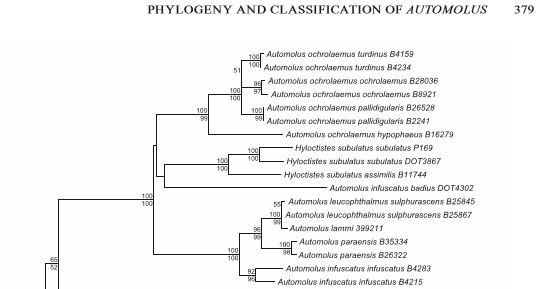

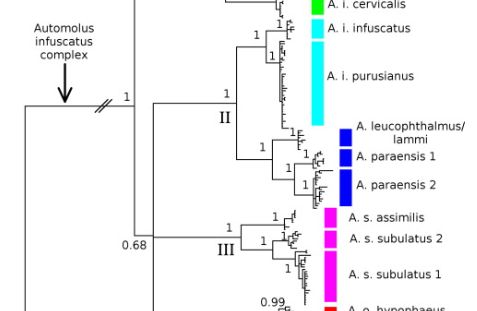

Genetic differences have been documented in Claramunt et al. (2013). Although both groups

unsurprisingly are sisters (assimilis represents the virgatus group),

divergence seems to have occurred earlier than is the case e.g. in species of

the infuscatus complex.

and more recently also documented by

Schultz et al. (2017):

Although sonograms of cordobae now definitely

confirm it belongs to the western group, the remark in proposal 40 about a

peer-reviewed paper documenting voice remains. The incentive for such a paper

is, however. lower than ever. On the other hand, we have now a note quantifying

vocal differences, a paper documenting playback response, and genetic studies

indicating fairly high genetic divergence.

See:

Boesman, P. (2016). Notes

on the vocalizations of Striped Woodhaunter (Hyloctistes

subulatus).

HBW Alive Ornithological Note 90. In: Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive.

Lynx

Edicions, Barcelona. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow-on.100090 https://static.birdsoftheworld.org/on90_striped_woodhaunter.pdf

Claramunt,

S.; Derryberry, E.P.; Cadena, C.D.; Cuervo, A.M.; Sanín, S.; Brumfield, R.T.

(2013). Phylogeny and classification of Automolus foliage-gleaners

and allies (Furnariidae). Condor. 115 (2): 375–385.

Schultz,

E., Burney, C.; Brumfield, R.; Polo, E.; Cracraft, J., Ribas, C. (2017)

Systematics and biogeography of the Automolus infuscatus complex (Aves;

Furnariidae): Cryptic diversity reveals western Amazonia as the origin of a

transcontinental radiation. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 107:503-515.

754C.

Elevate Grallaria alticola to species

rank

Effect

on SACC: Elevate Grallaria alticola to

species rank (split from G. quitensis).

Background:

Grallaria quitensis inhabits high

elevations (typically paramos) in the Northern and Central Andes. Three

allopatric subspecies differ in vocalizations, and, to a lesser extent,

plumage.

New

data: Freeman and Montgomery (2017) conducted playback experiments on 9

territories of quitensis in Ecuador

to measure response to alticola (restricted

to the Eastern Andes in Colombia). They found that 6 out of 9 territorial birds

in Ecuador discriminated against song playback of alticola (discrimination = fail to approach within 15 m of the

speaker). Perhaps relevant is that these two populations differ in ND2

sequences deposited on GenBank by 5.4% in uncorrected p-distance, which

suggests that the two populations may have evolved reasonably strong postmating

isolation as well, though this is speculative.

Competing

proposals:

1)

NO

= Retain the status quo.

2)

YES

= Elevate Grallaria alticola to

species rank.

Recommendation:

Birds from Ecuador respond strongly to local song, but, in the majority of

cases, ignore song from andicola

birds. This suggests that vocal differences constitute a strong premating

barrier to reproduction between these two taxa. I therefore recommend treating alticola and quitensis as distinct biological species. I am not aware of

existing English names; HBW uses “Northern Tawny Antpitta” for alticola and “Western Tawny Antpitta”

for quitensis; there may be better

options.

Additional material added by Peter Boesman:

Morphological

differences between the 3 races were summarized

in del Hoyo & Collar (2016) after studying a series of specimens.

Vocal differences have been quantified in Boesman (2016) and summarized in del

Hoyo & Collar (2017). The two main

vocalisations (‘song’ and ‘call’) differ significantly between all 3 races.

They are also described in Greeney (2018).

Genetic data can be found for 2 races in Winger et al. (2015) and suggest paraphyly:

“Grallaria quitensis quitensis was identified as the closest out-group

to the bay-backed antpittas. However, the sample of G. quitensis alticola

was recovered as sister to G. hypoleuca (Fig. 2A), rather than to G.

q. quitensis, with low support”.

This case obviously reminds me of the

recent publications about the Rufous Antpitta complex, with the three races of G.

quitensis actually being the higher altitude replacement of resp. G.(r.)

rufula, G. (r.) saturata, and G. (r.) gravesi, and thus -even

more than the latter trio- separated by regions of unsuitable habitat.

We have here a very analogous

situation of limited morphological divergence and significant vocal differences

among allopatric populations separated by geographical barriers.

It boils down to the question whether a peer-reviewed

paper is considered a requirement or if sufficient analogy with a

well-documented case can be used as a convincing argument.

See:

Boesman,

P. (2016). Notes on the vocalizations of Tawny Antpitta (Grallaria quitensis).

HBW Alive Ornithological Note 72. In: Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive.

Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow-on.100072 https://static.birdsoftheworld.org/on72_tawny_antpitta.pdf

Greeney,

H. (2018) Antpittas and Gnateaters. Helm Identification Guides.

Winger

et al. (2015.) Inferring speciation history in the Andes with

reduced-representation sequence data: An example in the bay-backed antpittas

(Aves; Grallariidae; Grallaria hypoleuca s. l.) Molecular Ecology 24:6256-6277.

754D.

Elevate Scytalopus intermedius to

species rank

NOTE

from Remsen:

This proposal was superseded by SACC proposal 858.

Effect

on SACC:

Elevate Scytalopus intermedius to

species rank (split from S. latrans).

Background: Scytalopus latrans inhabits high elevations in the Northern and

Central Andes. Song is somewhat divergent between multiple populations. This

proposal focuses on two groups; the population of latrans found in southeastern Ecuador, and intermedius, which occurs in Peru south of the Marañon Gap.

New

data:

Freeman and Montgomery (2017) conducted playback experiments on 8 territories

of latrans in southeastern Ecuador.

They found that all 8 territorial birds in Ecuador discriminated against song

playback of intermedius (discrimination=

fail to approach within 15 m of the speaker).

Competing

proposals:

1)

NO=

Retain the status quo.

2)

YES

= Elevate Scytalopus intermedius to

species rank.

Recommendation: Birds from

southeastern Ecuador respond strongly to local song, but, in all cases, ignore

song from intermedius. This suggests

that vocal differences constitute a strong premating barrier to reproduction

between these two taxa, which are found on adjacent and opposite sides of the Marañon Gap. I therefore recommend treating

populations north and south of the Marañon Gap as distinct biological species. There

is marked variation in vocalizations within latrans

found north of the Marañon Gap, some of

which may be relevant in the future to species limits within the latrans group (= all population found

north of the Marañon Gap). I am not aware of

existing English name.

754E.

Elevate Ochthoeca thoracica to

species rank

Effect

on SACC:

Elevate Ochthoeca thoracica to

species rank (split from O.

cinnamomeiventris).

Background: Ochthoeca cinnamomeiventris is widely distributed in the tropical

Andes. Vocal and plumage variation is divergent between multiple populations.

This proposal focuses on two taxa; cinnamomeiventris,

found north of the Marañon Gap, and thoracica, which occurs in Peru south of

the Marañon Gap. These taxa differ in song and

plumage.

New

data: Freeman and Montgomery (2017) conducted playback experiments on 5

territories of cinnamomeiventris in

southeastern Ecuador. They found that all 5 territorial birds in Ecuador

discriminated against song playback of thoracica

(discrimination= fail to approach within 15 m of the speaker).

Competing

proposals:

1)

NO

= Retain the status quo.

2)

YES

= Elevate Ochthoeca thoracica to

species rank.

Recommendation: Birds from

southeastern Ecuador respond strongly to local song, but, in all cases, ignore

song from thoracica. This suggests

that vocal differences constitute a strong premating barrier to reproduction

between these two taxa, which are found on adjacent and opposite sides of the Marañon Gap. I therefore recommend treating cinnamomeiventris and thoracica as distinct biological

species. An English name currently used for thoracica

is “Maroon-belted Chat-Tyrant”; as far as I can tell, cinnamomeiventris is known as “Slaty-backed Chat-Tyrant,” which is

also the English name widely used for the entire complex.

Additional

material added by Peter Boesman:

Vocal differences have been quantified in Boesman (2016) and summarized in del Hoyo &

Collar (2017).

(The case of nigrita remains to be solved

(treated as a full species by IOC). However, a recording of mine of an unseen

bird (XC430652) sounds very much like cinnamomeiventris, and seems to

indicate limited vocal divergence.)

Genetic data can be found in Garcia-Moreno et al. (1998) (in which they propose a

split): “The genetic differentiation between cinnamomeiventris and thoracica

(0.053) is of the same magnitude as that between other sister species (e.g.,

0.039- 0.063 within the S. diadema group, 0.042 between 0. leucophrys

and 0. oenanthoides”. Also Cuervo (2013) reached similar conclusions.

We have thus here a suboscine case of two groups which

differ moderately in morphology, significantly in voice, and show a fairly deep

genetic divergence.

See:

Cuervo,

A. (2013). Evolutionary Assembly of the Neotropical Montane Avifauna. Thesis,

Louisiana State University.

García-Moreno

J., Arctander P., Fjeldså J. (1998) Pre-Pleistocene differentiation among

chat-tyrants. Condor 100:629-640.

Boesman,

P. (2016). Notes on the vocalizations of Slaty-backed Chat-tyrant (Ochthoeca

cinnamomeiventris). HBW Alive Ornithological Note 253. In: Handbook of the

Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions,

Barcelona. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow-on.100253 https://static.birdsoftheworld.org/on253_slaty-backed_chat-tyrant.pdf

754F.

Elevate Myadestes venezuelensis to

species rank

Effect

on SACC:

Elevate Myadestes venezuelensis to

species rank (split from M. ralloides).

Background: Myadestes ralloides is widely distributed in the tropical Andes.

Vocal variation is markedly divergent among populations of M. ralloides. This proposal focuses on two taxa; venezuelensis, found north of the Marañon Gap in eastern Ecuador, and ralloides, which occurs in Peru south of

the Marañon Gap.

New

data: Freeman and Montgomery (2017) conducted playback experiments on 12

territories of venezuelensis in

eastern Ecuador. They found that 10 out of 12 territorial birds in Ecuador

discriminated against song playback of ralloides

(discrimination= fail to approach within 15 m of the speaker).

Competing

proposals:

1)

NO

= Retain the status quo.

2)

YES

= Elevate Myadestes venezuelensis to

species rank.

Recommendation: Birds from eastern

Ecuador respond strongly to local song, but, in nearly all cases, ignore song

from ralloides. This suggests that

vocal differences constitute a strong premating barrier to reproduction between

these two taxa, which are found on adjacent and opposite sides of the Marañon Gap. I therefore recommend treating

populations north and south of the Marañon Gap as distinct biological species. I am

not aware of existing English names. There is further vocal variation between

populations living on the Pacific slope in western Ecuador and those on the

Amazonian slope in eastern Ecuador – these may also prove to constitute

distinct biological species, but our (unpublished) playback experiments between

these taxa is not sufficient to evaluate species limits at present.

Additional

material added by Peter Boesman:

Morphological differences are analyzed in del Hoyo & Collar (2016) based on specimens in AMNH

and indicate a yellower bill and a paler belly, but evidently, differences are

rather small.

Vocal

differences have been quantified in Boesman (2016). Southern ralloides

appears vocally the most distinctive taxon, with plumbeiceps vs venezuelensis

also showing smaller vocal differences.

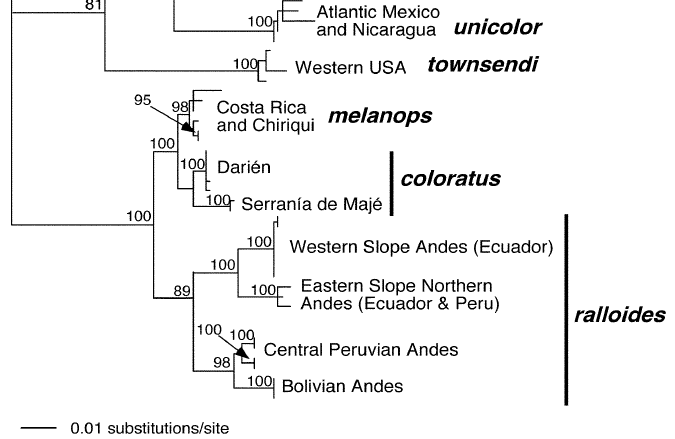

Genetic differences can be found in Miller (2007). “Average pairwise distances between M.

ralloides and M. coloratus (6.5%; range: 5.7–8.3%) and between M.

ralloides and M. melanops (6.0%; range: 5.9–8.0%) only slightly

exceeded the pairwise distance between M. ralloides populations across

the Marañon valley (6.0%; range: 5.3–7.3%). Pairwise distances between M.

coloratus and M. melanops averaged 2.0% (range: 1.4–3.6%), which is

similar to the shallowest divergence between phylogroups within M. ralloides.”

Cuervo (2013) reached similar conclusions.

This is thus a case somewhat similar to Catharus

dryas in terms of differentiation (proposal 865).

See:

Boesman,

P. (2016). Notes on the vocalizations of Andean Solitaire (Myadestes

ralloides). HBW Alive Ornithological Note 435. In: Handbook of the Birds of

the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow-on.100435 https://static.birdsoftheworld.org/on435_andean_solitaire.pdf

Cuervo,

A. (2013). Evolutionary Assembly of the Neotropical Montane Avifauna. Thesis,

Louisiana State University.

Miller,

M., Bermingham, E., Ricklefs, R. (2007). Historical biogeography of the new

world solitaires (Myadestes spp.) Auk 124:868–885.

754G.

Elevate Pheugopedius schulenbergi to

species rank

Effect

on SACC:

Elevate Pheugopedius schulenbergi to

species rank (split from P. euophrys).

Background: Pheugopedius euophrys is widely distributed in the Northern Andes.

Vocal and plumage variation is somewhat divergent between multiple populations.

This proposal focuses on two taxa; longipes,

found north of the Marañon Gap in eastern

Ecuador, and schulenbergi, which

occurs in Peru south of the Marañon Gap.

New

data:

Freeman and Montgomery (2017) conducted playback experiments on 19 territories

of longipes in southeastern Ecuador.

They found that 12 out of 19 territorial birds in Ecuador discriminated against

song playback of schulenbergi (discrimination=

fail to approach within 15 m of the speaker).

Competing

proposals:

1)

NO

= Retain the status quo.

2)

YES

= Elevate Pheugopedius schulenbergi to

species rank.

Recommendation: Birds from

southeastern Ecuador respond strongly to local song, but, in most cases, ignore

song from schulenbergi. This suggests

that vocal differences constitute a strong premating barrier to reproduction

between these two taxa, which are found on adjacent and opposite sides of the Marañon Gap. I therefore recommend treating

populations north and south of the Marañon Gap as distinct biological species. Schulenbergi is called “Grey-browed

Wren” by HBW.

Additional

material added by Peter Boesman:

Morphological differences are summarized in del Hoyo & Collar (2016).

Vocal

differences have been quantified in Boesman (2016).

Subspecies of P. euophrys show quite some

morphological differences in between them, as with schulenbergi. The

voice of schulenbergi is, however, remarkably different from all other subspecies,

and even for an oscine passerine with vocal learning ability this seems to be quite

a stretch to consider it a single species.

Some supportive genetic info is however highly

desirable.

There is also the case of the undescribed ‘Mantaro

Wren’, but until it is described as a new taxon, is better treated as a

potential future case.

See:

Boesman,

P. (2016). Notes on the vocalizations of Plain-tailed Wren (Thryothorus

euophrys). HBW Alive Ornithological Note 290. In: Handbook of the Birds of

the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow-on.100290 https://static.birdsoftheworld.org/on290_plain-tailed_wren.pdf

754H. Elevate Amazonian

populations of Tunchiornis ochraceiceps to

species rank

Effect

on SACC:

Elevate Amazonian populations of Tunchiornis

ochraceiceps to species rank (split from populations found west of Andes).

Background: Tunchiornis ochraceiceps consists of many named subspecies that are

found both west and east of the Andes. There is marked vocal and plumage

variation throughout its broad distribution.

New

data:

Freeman and Montgomery (2017) conducted playback experiments on 10 territories

of T. ochraceiceps in Costa Rica.

They found that 8 out of 10 territorial birds discriminated against song

playback from the western Amazonian ferrugineifrons

group (discrimination = fail to approach within 15 m of the speaker).

Competing

proposals:

1)

NO

= Retain the status quo.

2)

YES

= Split populations found west of the Andes from populations found east of the

Andes.

Recommendation: Central American

birds respond strongly to local song, but essentially ignore song from western

Amazonian birds. This suggests that vocal differences constitute a strong

premating barrier to reproduction between these allopatric taxa. It would be

nice to have done further playback experiments in western Colombia and western

Ecuador, but this was not possible. There are additional vocal differences

within both west-of-the-Andes and east-of-the-Andes groups. In sum, though this

is not as clear-cut as many of the other cases, I recommend treating the

populations found east and west of the Andes as distinct biological species. I

am not aware of existing English names that would be applied to

west-of-the-Andes vs. east-of-the-Andes groups.

Additional

material added by Peter Boesman:

Vocal differences have been analyzed in Boesman (2016). Three vocal groups were

identified. NW group differs from Amazon group by having higher-pitched shorter

whistles. Guianan group differs from Amazon group by having two-note whistles

at different pitch.

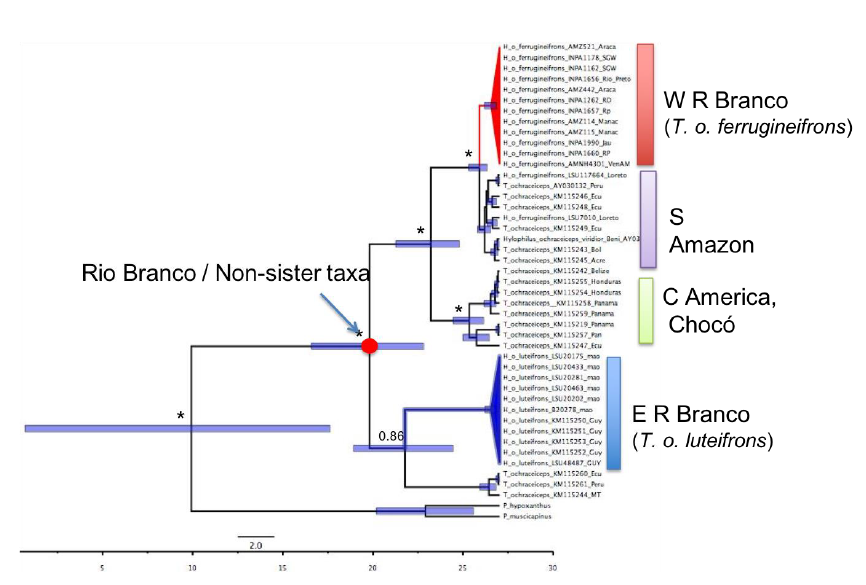

Genetic data are given in Naka and Brumfield (2018).

Genetic and vocal analysis seem to go hand-in-hand,

with luteifrons being most divergent, followed by NW populations vs

Amazon.

The situation of rubrifrons/lutescens is not

entirely clear however, and makes this case less clear-cut.

See:

Boesman,

P. (2016). Notes on the vocalizations of Tawny-crowned Greenlet (Hylophilus

ochraceiceps). HBW Alive Ornithological Note 168. In: Handbook of the Birds of

the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow-on.100168 https://static.birdsoftheworld.org/on168_tawny-crowned_greenlet.pdf

Naka,

L., Brumfield,R. (2018). The dual role of Amazonian rivers in the generation

and maintenance of avian diversity. Sci. Adv. 2018-4: 1-13.

754I. Elevate South

American populations of Basileuterus

culicivorus to species rank

Effect

on SACC: Elevate South American populations of Basileuterus culicivorus to species rank (split from populations

found in Central America).

Background:

Basileuterus culicivorus consists of

many named subspecies found throughout much of Central and South America. There

is marked vocal and plumage variation throughout its large distribution. This

proposal focuses on two allopatric taxa; godmani,

found in Costa Rica and Panama, and the cabanisi

group which occurs in nearby Colombia and Venezuela.

New

data: Freeman and Montgomery (2017) conducted playback experiments on 17

territories of godmani in Costa Rica.

They found that 13 out of 17 territorial birds discriminated against song

playback from the cabanisi group

(discrimination = fail to approach within 15 m of the speaker).

Competing

proposals:

1)

Retain

the status quo.

2)

Elevate

Basileuterus cabanisi to species

rank.

Recommendation:

Central American birds respond strongly to local song, but essentially ignore

song from cabanisi. This suggests

that vocal differences constitute a strong premating barrier to reproduction

between these allopatric taxa. Thus, I recommend treating the populations found

in South America as distinct from those in Central America. I note that species

limits within South American populations may require further evaluation.

English names: HBW uses “Stripe-crowned Warbler” for Central American

populations, “Yellow-crowned Warbler” for populations in Colombia and

Venezuela, and “Golden-crowned Warbler” for the additional South American

populations. We have no playback data to evaluate differences between the cabanisi group and other populations in

South America at this time. Still, the data we summarize above suggest that

Central American populations represent a distinct species from those in

adjacent northwestern South America; thus this proposal.

Additional

material added by Peter Boesman:

Vocal differences have been analysed in Boesman (2016). Three vocal groups were

identified. These seem to go

hand-in-hand with the three morphological groups (Curson et al. 1994),

and led del Hoyo and Collar (2016) to assign them species rank.

Genetic data is provided in Vilaca et al. (2010), who identified 5 clades.

Unfortunately, out of ca. 150 samples, only 2 were from the cabanisi

group (1 taxon). Nevertheless, it would seem that the South American subspecies

are a more recent colonisation from the East Mexico branch, which diverged

earlier from West Mexico. Thus, this seems to be a case in which evolution in

phenotypic traits have evolved at unequal rates in the distinct clades (which

as in other cases may lead to paraphyletic species).

(It is also suggested that B. hypoleucus may be

a colour morph of Golden-crowned Warbler, given there are no clear genetic of

vocal differences. This is however another case…)

See:

Boesman,

P. (2016). Notes on the vocalizations of Golden-crowned Warbler (Basileuterus

culicivorus). HBW Alive Ornithological Note 380. In: Handbook of the Birds

of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow-on.100380 https://static.birdsoftheworld.org/on380_golden-crowned_warbler.pdf

Curson,

J., Quinn, D., Beadle, D. (1994). New World

Warblers. Helm Identification Guide. Helm. London.

Vilaca

S.T., Santos, F.R. (2010) Biogeographic history of the species complex Basileuterus

culicivorus (Aves, Parulidae) in the Neotropics. Molecular Phylogenetics

and Evolution 57: 585–597.

754J.

Elevate Myiothlypis chlorophrys to

species rank

Effect

on SACC:

Elevate Myiothlypis chlorophrys to

species rank (split from M. chrysogaster).

Background: Myiothlypis chrysogaster consists of two populations, one found in

the Choco in western Colombia and western Ecuador, and a second that inhabits

eastern Peru (and, narrowly, Bolivia).

These taxa are notably different in vocalizations and have been

considered to be distinct biological species by various authors.

New

data:

Freeman and Montgomery (2017) conducted playback experiments on 11 territories

of chlorophrys in western Ecuador.

They found that 10 out of 11 territorial birds discriminated against playback

of chrysogaster song (discrimination

= fail to approach within 15 m of the speaker). We also recently conducted two

playback experiments that showed that chrysogaster

discriminates against (ignores) chlorophrys

song (unpublished, and small sample size caveat, but I thought worth

mentioning).

Competing

proposals:

1)

NO

= Retain the status quo.

2)

YES

= Elevate Myiothlypis chlorophrys to

species rank.

Recommendation: Chlorophrys responds strongly to local song, but essentially

ignores song from chrysogaster. This

suggests that vocal differences constitute a strong premating barrier to

reproduction between these allopatric taxa. Thus, I recommend treating these

two populations as distinct biological species.

These taxa are sometimes referred to by the English names “Choco

Warbler” (for chlorophrys) and “Cuzco

Warbler” (for chrysogaster).

Additional

material added by Peter Boesman:

Proposal 68 (2003) already tackled this case. However, in those

days lack of sonograms etc. did not allow for a proper comparison.

Morphological differences were summarized in del Hoyo and Collar (2016): chlorophrys has a

broad green vs narrow yellow post-ocular supercilium, more olive flanks and

shorter tail.

Vocal differences have been analysed in Boesman (2016), identifying two very

distinct vocal groups (chrysogaster and chlorophrys).

Genetic data: Lovette et al (2010) only included the chlorophrys taxon. The two taxa may not have not been compared yet

genetically.

See:

Boesman,

P. (2016). Notes on the vocalizations of Golden-bellied Warbler (Basileuterus

chrysogaster). HBW Alive Ornithological Note 377. In: Handbook of the Birds

of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow-on.100377 https://static.birdsoftheworld.org/on377_golden-bellied_warbler.pdf

Lovette

et al. (2010). A comprehensive

multilocus phylogeny for the wood-warblers and a revised classification of the

Parulidae (Aves). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 57:753–770.

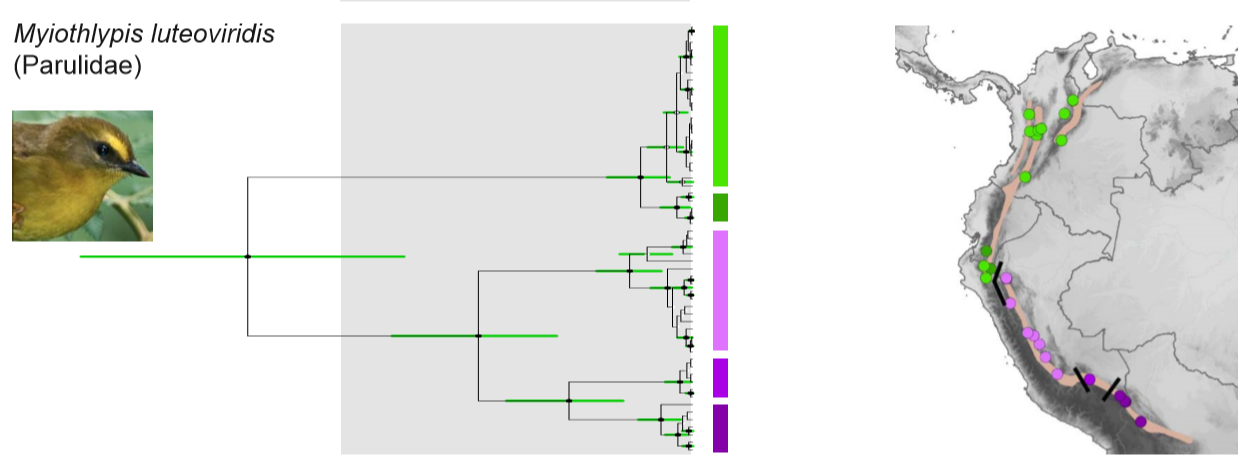

754K.

Elevate Myiothlypis striaticeps to

species rank

Effect

on SACC:

Elevate Myiothlypis striaticeps to

species rank (split from M. luteoviridis).

Background: Myiothlypis luteoviridis is widely distributed in the tropical

Andes. Vocal variation is somewhat divergent between multiple populations. This

proposal focuses on two taxa; luteoviridis,

found north of the Marañon Gap in eastern

Ecuador, and striaticeps, which

occurs in Peru south of the Marañon Gap.

New

data:

Freeman and Montgomery (2017) conducted playback experiments on 11 territories

of luteoviridis in southeastern

Ecuador. They found that 8 out of 11 territorial birds in Ecuador discriminated

against song playback of striaticeps (discrimination=

fail to approach within 15 m of the speaker).

Competing

proposals:

1)

NO

= Retain the status quo.

2)

YES

= Elevate Myiothlypis striaticeps to

species rank.

Recommendation: Birds from

southeastern Ecuador respond strongly to local song, but, in most cases, ignore

song from striaticeps. This suggests

that vocal differences constitute a strong premating barrier to reproduction

between these two taxa, which are found on adjacent and opposite sides of the Marañon Gap. I therefore recommend treating

populations north and south of the Marañon Gap

as distinct biological species. I am not aware of existing English names.

Additional

material added by Peter Boesman:

Vocal differences have been analysed in Boesman (2016), identifying several vocal groups,

with striaticeps and euophrys especially standing out.

Genetic data: Lovette et al (2010) only included the euophrys taxon. Cuervo

(2013) provided a genetic tree in which the Marañon gap creates the earliest

separation of northern and southern groups (>3Mio yrs).

The southern subspecies striaticeps and euophrys

are thus clearly genetically and vocally distinct.

See:

Boesman,

P. (2016). Notes on the vocalizations of Citrine Warbler (Basileuterus

luteoviridis). HBW Alive Ornithological Note 438. In: Handbook of the Birds

of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow-on.100438 https://static.birdsoftheworld.org/on438_citrine_warbler.pdf

Cuervo,

A. (2013). Evolutionary Assembly of the Neotropical Montane Avifauna. Thesis.

Lovette

et al. (2010). A comprehensive

multilocus phylogeny for the wood-warblers and a revised classification of the

Parulidae (Aves). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 57:753–770.

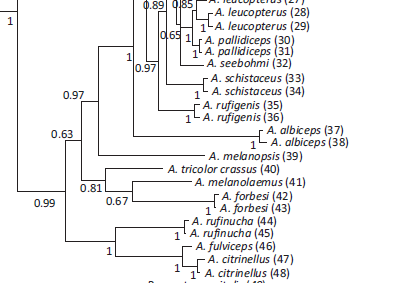

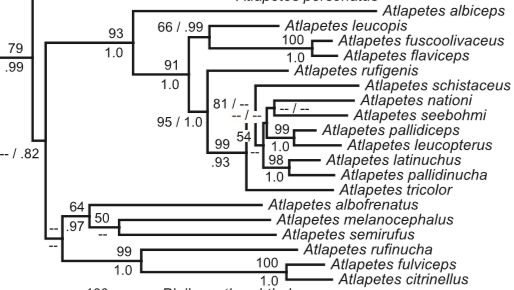

754L.

Elevate Atlapetes tricolor crassus to

species rank

Effect on SACC: Elevate Atlapetes tricolor crassus to species

rank

Background: Atlapetes tricolor consists of two populations, one found in the

Choco in western Colombia and western Ecuador, and a second that inhabits

eastern Peru (and, narrowly, Bolivia).

These taxa are notably different in vocalizations (and morphology) and

have been considered distinct biological species by several authors.

New

data:

Freeman and Montgomery (2017) conducted playback experiments on 6 territories

of crassus in western Ecuador. They

found that 5 out of 6 territorial birds discriminated against playback of tricolor song (discrimination = fail to

approach within 15 m of the speaker).

Competing

proposals:

1)

NO=

Retain the status quo.

2)

YES

= Elevate Atlapetes crassus to

species rank.

Recommendation: Atlapetes crassus responds strongly to local song, but essentially

ignores song from tricolor. This

suggests that vocal differences constitute a strong premating barrier to

reproduction between these allopatric taxa. Thus, I recommend treating these

two populations as distinct biological species. “Choco Brush-Finch” has been

used for crassus and “Tricolored

Brush-Finch” for tricolor.

Additional

material added by Peter Boesman:

Morphological differences are summarized in del Hoyo and Collar (2016).

Vocal differences have been analysed in Sanchez-Gonzalez et al. (2015) and Boesman (2016).

Genetic data: Sanchez-Gonzalez et al. (2015) only included crassus,

and Klicka et al. (2014) only included tricolor. They were found at

different locations in the gene tree:

Sanchez-Gonzalez et al. (2015) summarizers: “In the

taxa investigated, the subspecies were found to differ little from each other

vocally, but one exception is A. t. crassus and tricolor, which

are distributed in western Colombia and Ecuador, and 900 km away in central

Peru. They also differ in elevational distributions 300–2000 m against

1750–3050 m) and morphologically (crassus with bill much larger, crown,

back and underparts differently coloured). We suggest that the northern form is

best treated as a full species: Choco Brush-Finch Atlapetes crassus. In

fact, the study by Klicka et al. (2014) included samples of A. t. tricolor

from Peru and recovered it as sister to our clade H, which includes Atlapetes

from a clade including mainly eastern Andean slope forms, widely separated from

our Ecuadorian A. t. crassus sample, thus confirming the taxonomic

differentiation in these two taxa.”

See:

Boesman,

P. (2016). Notes on the vocalizations of Tricolored Brush-finch (Atlapetes

tricolor). HBW Alive Ornithological Note 365. In: Handbook of the Birds of

the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow-on.100365 https://static.birdsoftheworld.org/on365_tricolored_brush-finch.pdf

Klicka,

J., Keith Barker, F., Burns, K. J., Lanyon, S. M., Lovette, I. J., Chaves, J.

A. & Bryson, R. W., Jr (2014). A comprehensive multilocus assessment of

sparrow (Aves: Passerellidae) relationships. Molecular Phylogenetics and

Evolution 77: 177–182.

Sánchez-González,

L.A., Navarro-Sigüenza, A.G., Krabbe, N.K., Fjeldså, J., García-Moreno, J.

(2015). Diversification in the Andes: the Atlapetes

brush-finches. Zool. Scripta 44(2): 135– 152.

754M. Elevate Amazonian

populations of Arremon aurantiirostris to

species rank

Effect

on SACC: Elevate Amazonian populations of Arremon

aurantiirostris to species rank (split from populations found west of

Andes).

Background:

Arremon aurantiirostris consists of

many named subspecies that are found both west and east of the Andes. There is

marked vocal variation throughout its distribution.

New

data: Freeman and Montgomery (2017) conducted playback experiments on 23

territories of occidentalis in

western Ecuador, and playback experiments on 12 territories of spectabilis in eastern Ecuador. They

found that 16 out of 23 territories of occidentalis

discriminated against playback of spectabilis

song, and that 8 out of 12 territories of spectabilis discriminated against playback of occidentalis song

(discrimination = fail to approach within 15 m of the speaker).

Competing

proposals:

1)

NO

= Retain the status quo.

2)

YES

= Elevate Amazonian Arremon aurantiirostris

spectabilis to species rank.

Recommendation:

Arremon aurantiirostris populations

in western and eastern Ecuador respond strongly to local song, but, in most

cases, ignore song from each other. This suggests that vocal differences

constitute a strong premating barrier to reproduction between occidentalis and spectabilis. Thus, I recommend treating these two populations as

distinct biological species. I note that this complex likely harbors additional

biological species (e.g., in Central America, populations on the Caribbean and

Pacific slope show strong song discrimination). Thus, if this split is adopted,

it should be recognized that this is not the end of the story (including

choosing English names that would minimize confusion in the case of additional

splits).

Comments

from Stiles: "This

is a most interesting proposal! However,

while highly suggestive of biological isolating mechanisms, in most of the

individual cases presented I consider that the data presented are insufficient

for SACC acceptance, for the following reasons:

1) Most of the cases presented involved

presenting the song of one population to members of another; reciprocal

playbacks would have been more convincing, as asymmetry in responses have been

found in some other studies;

2) The 60% no-response threshold presented was

insufficiently justified: just how much variation exists in this threshold

(which was based upon a general average of nine such comparisons of subspecies

vs. species responses); it would be helpful to know how much variation occurred

around this value, and whether the “threshold” might vary between oscines vs.

suboscines, especially given that several of the comparisons presented barely

exceed this “threshold”.

3) Several of the comparisons were made between

populations on either side of the Marañón gap; it is often not clear how close

these were to the “dividing line” (in at least one case, a subspecies closer to

the gap exists, but was not sampled). In other cases, the author did not

specify how closely the respective populations approach each other, and how

distant the sampled populations were from the point of closest approach;

4) No spectrographic analyses were made of

multiple recordings to evaluate possible intrapopulation variation, which might

influence the results in several cases; song dialects mediated by learning and

cultural transmission are known in oscines;

5) In several cases, important distributional

gaps occur between the populations sampled in which song variation is known to

exist between sampled and unsampled populations (subspecies), which could

easily influence interpretation of the results;

6) For nearly all cases, genetic data would

have helped to clinch the decision, but only for two cases were such data

presented;

7) The lack of nomenclatural precision often

makes the results difficult to apply, as in a number of cases, the taxa

involved are polytypic, which at a minimum would require a detailed study of

distributions and name priorities essential for arriving at concrete names for

the putative species; in several such cases, the subspecies sampled were not

given;

8) For a number of cases, pertinent

investigations are underway (or planned), especially where vocal differences of

unsampled populations may very well exist (a similar case in another SACC

proposal regarding Henicorhina

leucosticta did not pass for this

reason). I note that none of the experiments were performed in Colombia, which

would have been a strategic area for deciding several cases. Such cases in the

present proposal may best be taken as pointers for more comprehensive analyses.

"All

this is not to say that any of the cases presented are incorrect in suggesting

that two (or more!) biological species are involved, but the data are

insufficient for SACC action as they stand.

It is also worth noting that several of these proposals were rejected by

SACC due to the lack of detailed spectrographic analysis of vocalizations: the

point at issue is whether playback experiments represent a sufficient surrogate

or substitute for such analysis. I conclude that if the experiments show

significant differences in responses to same vs. different populations, the

results may be taken as valid. However, when the differences are very close to

the threshold value or sample sizes are too small, I recommend caution in their

acceptance. I now mention each case, with respect to the problems described

above by letters:

754A: Pseudocolaptes-plumage,

genetic and reciprocal playbacks all support this split, so YES.

754B: Automolus-data

very suggestive; not clear which population of the subulatus group was taken (where in “Amazonia”?). Were reciprocal playbacks done for the two virgatus populations, which are at

nearly opposite ends of this group’s range? On the other hand, in proposal 40

treating this question, all members of the committee agreed that two species

were indicated, given the vocal differences, but most preferred to await a

study of sonograms (by Zimmer?) Although I am not aware that this study has

been published, I consider that the experiments by Freeman constitute at least

a partial surrogate that to me, tips the burden of proof onto those who would

maintain these two as conspecific, hence YES.

754C: Grallaria-unfortunately,

no experiments performed in Colombia, where the Eastern Andes population also

differs vocally from that inhabiting the Central Andes, which would seem to be

in limbo: the same as the SE Ecuador population or not? Therefore, the data

here are incomplete; although genetic data suggest that the two populations

sampled represent different species, data from the C Andes birds in Colombia

are needed to complete the picture, and I suggest a tentative NO.

754D: Scytalopus-here

again, the data represent just the tip of the iceberg, since both north and south

of the Marañón gap there exist several subspecies with different plumages.

Daniel Cadena has been collecting genetic and vocal data on as many named Scytalopus taxa as possible, and may be

nearer to doing a comprehensive treatment of the latrans group. Hence, although the data show that at least two

biological species may well exist in this assemblage, I feel that any decision

should await more comprehensive data, so NO

for now.

754E: Ochthoeca-another

case where multiple, well-defined subspecies exist, especially N of the Marañón

gap, according to plumage; presumably the Ecuador sample was of subspecies; a

sample of only five experiments with thoracicus

from S of the Marañón and here again, I consider the data very suggestive

but incomplete: NO for now.

754F: Myadestes-nominate

ralloides was named from Bolivia

(from where were taken the recordings used for this form?); venezuelensis from Venezuela; SE Ecuador

is a long way from its type locality. Here, a detailed examination of

intraspecific variation in song from intermediate populations (e.g., in

Colombia and, depending on the above, N Peru) of these oscines (where song

learning and cultural transmission of song dialects could well occur) should be

done, and genetic data might also help: once again, I consider the experiments

presented here highly suggestive, but the data are as yet incomplete: NO for now.

754G: Pheugopedius-the

SE Ecuador population (longipes, N of

the Marañón gap) was tested against schulenbergi,

S of this gap: however, another subspecies (atriceps)

occurs closer to this gap than schulenbergi

and was not sampled. Intrapopulation variation in songs was not mentioned. So,

once more, the data are highly suggestive, but gaps remain. Also, the observed

non-response percentage (63%) was very close to the “threshold” (see above), so

NO for now.

754H: Tunchiornis-a

widespread species, the nominate subspecies found from Mexico to W Panama, whereas

cis-Andean ferrugineifrons occurs in

S Venezuela, Colombia and perhaps S to EC Peru. Although the exact site from

which the sample recording(s?) of the latter were taken was not given, evidence

for species status of cis- vs. trans-Andean populations sampled is certainly

suggestive. However, given the wide range of both forms, I am uneasy because

there could well be vocal variation within both forms; hence, I think that more

populations should be sampled for a conclusive answer: NO for now.

754I: Basileuterus

culicivorus-this is a highly polytypic species, with several named

subspecies in both Middle and South America. The tested population was godmani of Costa Rica to W Panamá, but

the provenance of the recording of the “cabanisi

group” was not specified (at least three subspecies of culicivorus occur in Colombia and Venezuela, and several more in

cis-Andean South America). Clearly, a much wider sample of the various

subspecies would be desirable, along with an evaluation of within-subspecies

variation in at least some of these. Population genomics within this species

would also be very interesting. Hence, I consider the available evidence too

incomplete to justify this split at present; NO for now.

754J: Basileuterus

chrysothlypis- This experiment dealt with a northern, trans-Andean

subspecies (chlorophrys) and a more

southern cis-Andean subspecies (nominate

chrysothlypis); these two are thus widely separated geographically, such

that parapatry is not relevant (or possible).

No other subspecies exist in this group. Here, the vocal evidence is

stronger (including a very small sample of reciprocal playbacks). Although

sonograms and genetic evidence would surely clinch the case, the available data

seem to me to tip the burden of proof towards conspecifity, hence a tentative YES.

754K:. Myiothlypis

luteiventris-Another comparison of subspecies N vs. S of the Marañón gap.

The song differences, as described by Schulenberg et al. (2009) certainly seem considerable, but with only 8 of 11

(73%) no-responses of the northern luteiventris

to songs of the southern striaticeps,

the results should be considered tentative at present. Also, a subspecies

further south (euophrys) shows

greater morphological differences from striaticeps

as well as possibly greater differences in song. So: NO for now, pending more data.

754L: Atlapetes-This case is similar to no. 10

in comparing cis- and trans-Andean populations, but with a much smaller sample

size (6); given that Atlapetes songs

tend to be complex, intraspecific variation could exist. I consider the

available evidence to be very suggestive but not conclusive, so NO for now.

754M: Arremon-This

is another tip-of-the iceberg case, because aurantiirostris

includes multiple subspecies with subtle morphological differences between

them over a wide range (including two from Costa Rica, that differ noticeably

in song). Hence, this result represents a small part of a much bigger problem.

Because Jorge Avendaño is now investigating this problem in depth, I believe

that any action by SACC should await the results of this study: NO for now.

Comments from Cadena: “I am going to vote NO on

all these proposals out of principle. I think that the hard work done by Ben

Freeman is exremely important and interesting, and is arguably the best

evidence we have to evaluate species limits in these groups of birds. However,

I agree with all the concerns voiced by Gary, especially with that related to

the 60% threshold for discrimination. I am not sure exactly what this means,

but say that 60% of the time, females of taxon A meeting males of taxon B

discriminate against them. What happens the rest of the time? If on 40% of the

encounters females of A do not discriminate against males of B, then inter-taxa

matings would be extremely frequent and one would expect hybridization to be

rampant, no? Maybe not, but then one should carefully consider other sources of

evidence together with the playback data, which takes me to a general

suggestion I have on all this. I think that the “bare-bones” approach taken by

Ben leaves several open questions and suffers importantly from lack of detail.

My suggestion is that all this should be placed in a paper (or papers) where

the ranges of the taxa involved are properly described, variation in different

characters is analyzed, and nuances of each case are discussed in detail to

reach more informed decisions. There are several potential theses projects here

for undergraduates with an interest in integrative taxonomy of birds in which

Freeman et al. have already made important progress.”

Comments from Jaramillo: “A – YES mainly due

to fact that this is a suboscine, and the genetic data.

B – YES

C – YES. The issue of

other populations in Colombia which may also differ, or perhaps muddy this picture

can be dealt with when those data appear.

D – YES. Scytalopus are so clear cut in response

to playback, that I find that this may be enough, even though there may be

other populations that should be sampled in the future. Or other molecular data

will arrive in the future.

E – NO. Kind of on the

fence on this one. But 5 experiments seems awful few.

F – YES. Note also that Miller et al. 2007 published

mtDNA data that also suggests a split north and south of the Marañon gap. Paper

is available here. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Matthew_Miller3/publication/228644579_Historical_biogeography_of_the_new_world_solitaires_Myadestes_spp/links/00b7d521e0aefa5c7c000000.pdf

G – NO. I would like to

see more data here, 12 out of 19 is a lot of birds that did react positively.

More data is necessary in this case.

H – NO. Given the huge

variation in this species, I think a more widespread set of experiments, is

necessary.

I - NO, but not because I do not believe that

there are multiple species here. But this one is one of those complex ones with

possibly multiple species involved, furthermore B. hypoleucus may in fact be conspecific with one of these forms.

So, it is complicated enough that I would rather base changes on the Vilaca

& Santos (2010) paper. Copy available here: https://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/46692562/Biogeographic_history_of_the_species_com20160621-14843-6idjqj.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAIWOWYYGZ2Y53UL3A&Expires=1522809006&Signature=X%2FzDXcNowKX2AzmZ6ykEM8dpuNc%3D&response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%3DBiogeographic_history_of_the_species_com.pdf

J – YES

K – YES, but tentative.

L – YES. Available

molecular data corroborates. Sanchez-Gonzales et al. (2014) found that crassus was in a group with A. melanolaemus and A. forbesi. While Klicka et al. (2014) sampled A. tricolor tricolor and found it was in an entirely different

clade with schistaceus, latinuchus

etc. Sanchez-Gonzales et al. (2014) also confirm clearly defined differences in

song of tricolor and crassus.

Klicka, J., Keith

Barker, F., Burns, K. J., Lanyon, S. M., Lovette, I. J., Chaves, J. A. &

Bryson, R. W., Jr (2014). A comprehensive multilocus assessment of sparrow

(Aves: Passerellidae) relationships. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 77,

177–182.

M- NO. Playback

experiments not quite conclusive here, and a very complex situation.

Additional

comments from Stiles:

“I recommended a YES on a few (!) of these, because I feel that they did tip

the balance on already accepted but

still controversial splits (i.e., not accepted by SACC but widely implemented

elsewhere). I also don’t feel

comfortable with a rather dogmatic NO to all without consideration of the

contexts involved.”

Comments

from Areta:

“I am also going to vote NO on all proposals, and I agree

with Daniel’s views. I agree with all the concerns voiced by Gary, and while I

appreciate the effort spent by both Alvaro and Gary in analyzing each case

separately, these analyses are not as thorough and complete as I would like to

have before me to make an informed decision. I especially feel that the 60%

threshold is rather artificial and insufficient. For example, by adding data on

reciprocal playback experiments of Upucerthia dumetaria/saturatior, Pseudocolopteryx

citreola/flaviventris and Poospiza nigrorufa/whitii (all of which

show 100% discrimination) this value can change easily. Not to mention other

Suboscines in which responses (even between sister species) are all or none.

Also, it troubles me that there are no reports of cases in which the local

population ignored its own local song and no assessment of whether the

playbacks were done at comparative times of the year (e.g., peak breeding

season, etc.). In sum, all these playback experiments are informative to

understand some key behavioral traits of possibly separate species, but the

taxonomically focused works needed to put these results in perspective are

missing (i.e., assessment of validity and priority of names, wide geographic

sampling, understanding of other phenotypic traits, evaluation of vocal traits

of intervening and/or other closely related populations, possibly genetic data,

etc.).”

Comments from Claramunt: “I agree with the several caveats raised by Gary regarding the evidence

presented by Freeman & Montgomery. In particular, unless there is evidence

of homogeneity within taxa, I’m skeptical about playback experiments involving

only two populations that are far apart as a way of assessing reproductive

isolation. At least, populations in close proximity or most likely to be in

secondary contact should be evaluated. Only interpreted together with other

information, the results of Freeman & Montgomery help to tip the balance in

some cases, as Gary stated. I think we should take advantage of this

opportunity to make decisions regarding species limits in light of this new bit

of information. Waiting for the ideal playback experiments is not an option, in

my opinion.

“A. YES to elevate Pseudocolaptes johnsoni to

species rank. With a

darker and more rufous plumage and a distinctly decurved culmen, johnsoni could be considered the most distinctive

taxon in its genus. As confessed by Zimmer (1936), it was only because of its

rarity (and scarcity of specimens) plus the uncertainty regarding its type

locality what made him treat johnsoni as a subspecies of lawrencii,

despite believing that it was a good species. Taxonomic inertia followed (with

few exceptions). Now we know that the song of johnsoni is very different and is not recognized by lawrencii.

A necessary and long overdue split.

“B. YES to

elevate Automolus virgatus to species rank. This complex shows considerable phenotypic variation that deserves

thorough study. Birds from the Choco region (assimilis) are darker and do not have the distinctive slender beak

of subulatus; they have instead a

more Automolus-like beak. However,

the slender beak, similar to that of subulatus,

reappears in Central America in virgatus,

although birds look much darker. A new relevant paper should also be

considered: Schultz et al. 2017 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1055790316304468). Schultz et al. 2017 found

that subulatus and assimilis represent two distinct genetic

groups divided by the Andes. Other subspecies were not sampled. mtDNA shows two

reciprocally monophyletic groups corresponding to subulatus and assimilis.

Nuclear data is harder to interpret because assimilis

was only sequenced for BF7, and BF7 alleles are messy across the entire genus.

However, the relevant information is that no BF7 alleles were shared between subulatus and assimilis (Supplemental Figure C7), thus suggesting no recent gene

flow. The clustering algorithm used (BAPS) failed to detect this separation

probably because of the missing nuclear data for the trans-Andean populations.

A pending question is whether assimilis

is indeed conspecific with virgatus

or represents a third species, an issue that could be addressed by studying the

Panamanian populations, where a contact zone could exist. In the meantime,

splitting Amazonian from trans-Andean forms is a step forward.

“C. NO to elevate Grallaria alticola to species rank. Playback

experiments show some degree of discrimination, but populations tested are far

apart. If song structure or song preference vary geographically, then the

experiments are irrelevant. No other traits differentiate Grallaria alticola,

except it body size, but a formal analysis of geographic variation is required

to determine if variation is continuous or discrete.

“D. NO to elevate Scytalopus intermedius to species rank.

Skimming over what is available in xeno-canto suggests tremendous and complex

variation in vocalizations in SE Ecuador and N Peru. The test based on just two

populations in this complex is not very informative of what is going on in the

region. Much more work is needed.

“E. YES to elevate Ochthoeca thoracica to species rank. Although

the number of independent experiments was low (5), this information should be

interpreted in light the additional information available. Plumage and song

variation is prominent and discrete, and matches the taxonomic divide. To the

eyes of the subspecies-lover ornithologist of the mid XX century, this

variation was only worth subspecific distinction. Freeman and Montgomery (2017)

showed that for the birds themselves, this variation means much more, and

suggest that these two separate lineages are reproductively isolated because of

divergent mating signals. Furthermore, a mitochondrial tree by Andres Cuervo (https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/275/),

including a large sample across the entire distribution of this complex, shows

that thoracica and cinnamomeiventris are reciprocally monophyletic, combining a

high degree of divergence and low intra-taxon genetic variability. Therefore,

multiple lines of evidence (phenotypic distinctness, playback experiments,

genetics) demonstrate that this pair of taxa constitute separate species.

Addendum. Note that Ochthoeca

thoracica and Ochthoeca cinnamomeiventris were treated as separate

species by Cory & Hellmayr and they were lumped later by Peters without

providing a rationale. So, this proposal should not be viewed as few playback

experiments in isolation but as evidence for whether two taxa that are

differentiated in plumage, song, and mtDNA are able to discriminate each other

based on playback experiments. Although sample size is not great, the answer

seems yes. So, for this case that has been historical in the borderline we

finally have evidence of behavioural reproductive isolation.”

“F. NO to elevate Myadestes venezuelensis to species rank.

The playback experiments are suggestive but geographic variation in other

traits needs to be studied.

“G. NO to elevate Pheugopedius schulenbergi to species

rank. Song discrimination was partial and geographic variation in songs and

plumage is high across the complex.

“H. NO to elevate

Amazonian populations of Tunchiornis

ochraceiceps to species rank. There is much geographic variation in this

complex and a test of reproductive isolation based on just two distant

populations is not very informative. Moreover, the mitochondrial tree of Naka

& Brumfield (2018, http://advances.sciencemag.org/content/4/8/eaar8575) indicates that Amazonian populations are paraphyletic because

trans-Andean populations are nested within them. Therefore, the situation is

complex and warrants more studies before redefining species limits.

“I. NO to elevate South

American populations of Basileuterus

culicivorus to species rank. Song discrimination was partial, and the

population tested was far away from the potential contact zone. Also,

geographic variation in songs and plumage is high across the complex, and a

phylogeographic study did not recovered the central American taxa as

monophyletic (Vilaça & Santos 2010, Mol. Phyl. Evol. 57:585-597).

“J. YES to elevate Myiothlypis chlorophrys to species rank.

I don’t have much additional information on this case. The two taxa are widely

allopatric. Plumage differences seem subtle, but that is typical in this genus.

On the other hand, songs differ dramatically and Freeman and Montgomery (2017)

showed that birds discriminate strongly against songs from the other taxon.

“K. NO to elevate Myiothlypis striaticeps to species rank.

These forms are phenotypically very similar, and some Ecuadorian birds did

respond to alien songs. So, I don’t see compelling evidence for a separation.

“L. YES to elevate Atlapetes tricolor crassus to species

rank. Not mentioned by the proposal is the possibility that tricolor and crassus are not each other’s closest relatives: tricolor seems to be related to schistaceus, seebohmi and related species (Klicka et al. 2014 Mol. Phyl. Evol. 77:177-182), whereas crassus forms a clade with melanolaemus and forbesi (Sánchez González et al. 2015 Zoologica Scripta

44:135–152). I know that this does not make sense biogeographically or plumage-wise,

and needs to be corroborated by an analysis in which the two forms are analyzed

together. But taken together, songs, phylogeny, and playback experiments all

point to separate status for these two forms despite plumage similarity, which

we know is highly homoplastic in Atlapetes.

“M. NO for now to

elevate Amazonian populations of Arremon

aurantiirostris to species rank. We have a small series of specimens of at

the ROM, and it strikes me as very distinct: short and decurved culmen, orange

underwings (instead of yellow), and other details. I think that it is a

different species. Not sure how it was decided that it belongs into aurantiirostris. However, it has been

treated as a subspecies of aurantiirostris

forever. and playback experiments show that they recognize each other to some

degree, so I would wait for the forthcoming more detailed study.”

Summary

comments from Peter Boesman (see individual contributions to each subproposal

in the main proposal):

“I personally believe that -staying at the conservative side- at

least case A, B, E, F, J and L should go through. (I am also quite convinced about C and G, but

am aware there is little published evidence)”

Additional

comments from Claramunt of 754C: “Regarding Grallaria

alticola, a clarification regarding the phylogenetic evidence: only in the

mtDNA the two samples analyzed by Winger et al. (one of alticola and one

of quitensis) did not appear as sister, but this results lacked strong

statistical support. The genomic dataset, in contrast, showed the two samples

as sister with moderate to strong support (Fig. 2B). Therefore, although the

genetic distance between the two samples was high in both cases, it seems that

they are sister taxa.

“Morphological differences seem slim, as far as I can see, and the

playback experiments revealed only partial discrimination, suggesting that the

differences in songs are not that significant for the birds.

“So, I maintain my NO on this sub proposal.”

New

comments from Jaramillo: “Very little change. No comments

on the ones where there was no change. Some additional comments where confusion

arose or perhaps now data is better but suggests a more complex re-organization

that may require a new proposal? Here we

go:

A – YES

B – YES

C – YES.

D – YES.

E – YES -

this is a change from my previous vote. Based on the new information,

characterization of vocal differences and published genetic data

F – YES

G – NO

H – NO. I

am confused here now. No change from my previous voting. However, it seems like

the new genetic and vocal data suggests that the real outlier is the Tepui

population. So perhaps this should be expanded as a new proposal? I am not sure

how to deal with this one. But something is going on here.

I - NO, see

my previous comments. May require re-writing this one as a new proposal? More

information needs to be unpacked for this one.

J – YES

K – YES,

now stronger based on new data.

L – YES.

M – NO.

Playback experiments not quite conclusive here, and a very complex situation.”

New comments from Stiles: “To

begin with, I believe that it is incumbent upon us to take this proposal

seriously enough to evaluate each subproposal based not only upon the playbacks

themselves, but such other evidence as exists in each case. Much additional evidence

has been gathered by Boesman for most of the proposals that merit

consideration. I am impressed by his careful evaluation of vocal differences in

particular, and he has brought to bear several pertinent sources not readily

available (e. g., Andrés Cuervo’s thesis). With reference to Santiago’s comment

that Freeman did not report results of playbacks of one population to its own

songs, Freeman stated that all such “sympatric” playbacks produced strong

positive reactions (approach to 15 m or less), although he did not give the

number of same for each case. Considering that the alternatives in each case

are to retain the status quo (a single species) or split this into two, I think

that one must decide whether the information presented is sufficient to tip the

burden of proof from those favoring the split onto those who would maintain the

status quo. However, this with the qualifier that although the evidence may

favor the two-way split, the proposal is embedded within a wider problem

requiring further work to disentangle. I might also mention that in some cases,

the method used for the playbacks could bias the results. A positive result for

an “allopatric” experiment (i.e., playing the voice of one population to a bird

of a distinct population) could produce some degree of approach simply because

of its novelty to the recipient: in effect, mere curiosity rather than an

aggressive response.

“On to specifics: my votes for all subproposals:

A.

YES to split Pseudocolaptes

johnsoni from P. lawrencii. Boesman