Proposal (778) to South

American Classification Committee

Note

from Remsen: Below is a proposal submitted to, passed by, and adopted

by NACC; see latest NACC Supplement in Auk 2017). For NACC members’ comments on this proposal,

see: http://checklist.aou.org/nacc/proposals/comments/2017_B_comments_web.html, proposal

2017-B-5). This is a version modified

for SACC.

Revise the

classification of the Icteridae: (A) add seven subfamilies; (B) split Leistes from Sturnella; and (C) modify the linear sequence of genera

Background:

Our current classification of the Icteridae largely follows Dickinson (2003). We do not recognize any subfamilies, and the

sequence of genera is as follows:

Psarocolius

Cacicus

Amblycercus

Icterus

Dives

Macroagelaius

Gymnomystax

Hypopyrrhus

Lampropsar

Gnorimopsar

Curaeus

Anumara

Amblyramphus

Agelasticus

Chrysomus

Xanthopsar

Pseudoleistes

Oreopsar

Agelaioides

Molothrus

Quiscalus

Dolichonyx

Sturnella

New information: Scott Lanyon’s lab has been working on a

gene-based phylogeny of the Icteridae for a couple of decades. This culminated in the paper by Powell et al.

(2014), which built a comprehensive phylogeny for the family based on a variety

of nuclear and mitochondrial loci for all 108 species, including whole

mitochondrial genome sequences for 23 species.

Remsen et al. (2016) used these data to propose a revised classification

of the family:

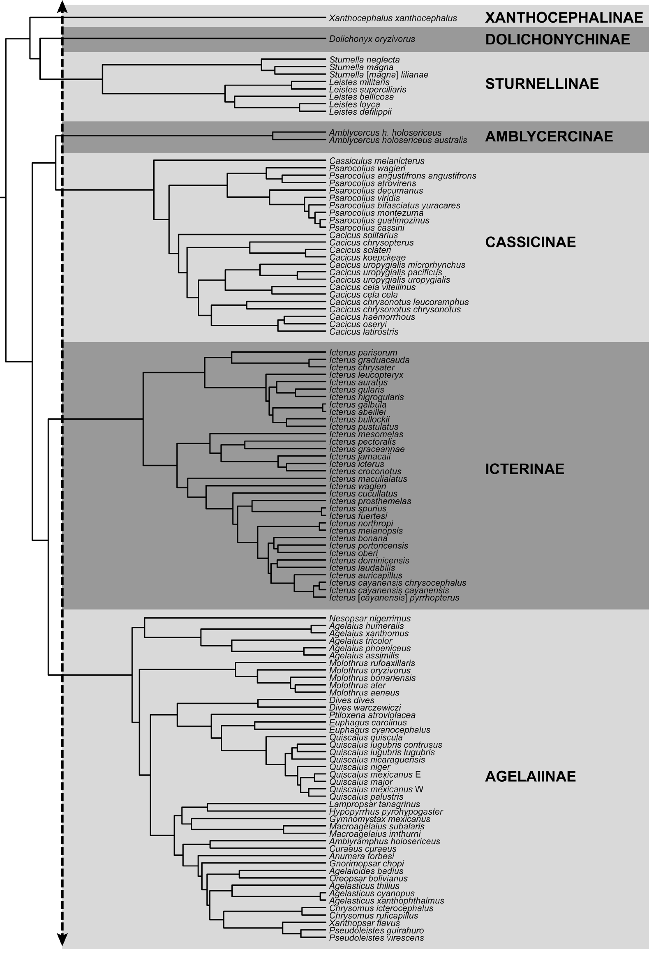

FIGURE 1. Phylogeny of

the New World blackbirds (Icteridae) inferred from mitochondrial and nuclear

DNA sequences of 118 taxa (outgroups not shown)—topology taken from the best

tree found under maximum likelihood by Powell et al. (2014; fig. 4); branch

lengths estimated in BEAST 1.7.4 (lognormal uncorrelated relaxed clock model for

mtDNA, strict clock for nDNA; Drummond et al. 2012) using the same data and

mitochondrial partitioning as Powell et al. (2014), but nuclear sequences

partitioned by locus. Dashed line marks the threshold used to assign subfamily

ranks. Species are listed in the order given by this tree topology and

(starting from the deepest node) following the conventions of listing the taxon

in the least-diverse clade first, or for equally diverse clades, the

northwestern-most lineage first.

The

biggest surprise is that extralimital Xanthocephalus

(Yellow-headed Blackbird) isn’t just another yellow-headed blackbird but an old

lineage that is sister to all other icterids.

The other major surprise is that Amblycercus

(Yellow-billed Cacique) is sister to all other caciques and oropendolas. As can be seen in the tree, the family

separated into seven lineages relatively early in its history, all roughly 8

million years old. Given this deep divergence,

we proposed subfamily rank for each of the seven lineages.

Most of

the revisions in generic boundaries had been published in previous papers and

have already been dealt with by NACC (e.g., expanded Molothrus) and SACC. The

exception was the proposed split of Leistes

from Sturnella. (The authors disagreed among themselves on

whether to split Icterus into two

genera, but such a split would require a new genus name.) We also devised a linear sequence to reflect

these phylogenetic data, following standard conventions.

Analysis and Recommendation: This proposal is

divided into 4 parts:

A. Recognition

of seven subfamilies. Note that the

name Cassicinae was corrected to Cacicinae by Schodde

& Remsen (2016). I recommend a YES

on this because these designations mark seven divergent lineages. I think the only area for debate, other than

whether to recognize any subfamilies at all, is whether to place Amblycercus in its own subfamily vs.

including it in same subfamily as the caciques and oropendolas. We decided to do this because this split is

as old as the other major splits in the family and to also call attention to

how divergent this bird is from other “caciques.”

B. Split

Leistes from Sturnella. The South American group was previously treated in

either Leistes or Pezites until Short (1968) provided

rational for the merger by pointing out the plumage and morphological

similarities among the meadowlarks. What

Short did not take into account (and in some cases, could not have known in the

pre-gene-based phylogenetic era) was how conservative plumage evolution is in

the family in general. For example, as

shown by the Lanyon lab, the South American blackbirds long included in Agelaius are only distantly related to

them despite similar plumage features.

As you can see from the tree, the split between North American and South

American members of broadly defined Sturnella

is deeper and thus presumably older than that between any two genera in the

tree. Therefore, I recommend a return to

the pre-Short treatment of the South American species in a separate genus. recommend a YES on splitting Leistes from Sturnella (which has already been done by Dickinson &

Christidis 2014). Tangentially, perhaps Alvaro

would be interested in doing a proposal for resurrecting Pezites for those species within Leistes.

C. Revise linear sequence. Remsen et al. (2016) used the standard

conventions for converting a phylogeny to a linear sequence (e.g., taxa from

least-diverse branch first; allotaxa arranged NW to SE) to produce the following

sequence (here pruned to reflect only the genera in SACC area). I recommend a YES for this.

Dolichonyx

Sturnella

Leistes

Amblycercus

Psarocolius

Cacicus

Icterus

Molothrus

Dives

Quiscalus

Lampropsar

Hypopyrrhus

Gymnomystax

Macroagelaius

Amblyramphus

Curaeus

Anumara

Gnorimopsar

Agelaioides

Oreopsar

Agelasticus

Chrysomus

Xanthopsar

Pseudoleistes

References:

DICKINSON, E. C., AND

L. CHRISTIDIS (eds.). 2014. The Howard

and Moore complete checklist of the birds of the World. Vol. 1. Passerines.

Aves Press, Eastbourne, U.K., 752 pp.

POWELL, A. F. L. A., F.

K. BARKER, S. M. LANYON, K. J. BURNS, J. KLICKA, AND I. J. LOVETTE. 2013.

A comprehensive species-level molecular phylogeny of the New World

blackbirds (Icteridae). Molecular Phylogenetics

and Evolution 71: 94-112.

REMSEN, J. V., JR., A.

F. L. A. POWELL, R. SCHODDE, F. K. BARKER, AND S. M. LANYON. 2016. Revised classification of the Icteridae

(Aves) based on DNA sequence data.

Zootaxa 4093: 285–292.

SCHODDE, R. AND J. V.

REMSEN, JR. 2016. Correction of Cassicinae Bonaparte, 1853 (Aves, Icteridae) to Cacicinae

Bonaparte, 1853. Zootaxa 4162: 188.

SHORT, L. L. 1968. Sympatry of red-breasted meadowlarks in

Argentina, and the taxonomy of meadowlarks (Aves: Leistes, Pezites,

and Sturnella). American Museum

Novitates 2349: 1-40.

Van Remsen,

February 2018

__________________________________________________________

Comments from Stiles:

“A. Yes to 7 subfamilies.

“B. YES to splitting Leistes from Sturnella. A

very deep and old divergence justifies generic rank for Leistes.

C. YES; the sequence

follows logically from the genetic data.”

Comments from Jaramillo:

“A – YES.

“B – YES. I do wonder

if reinstating Pezites makes any

sense, or just looks good because of familiarity with it? As such, the two

small Leistes are not all that

different from the large Leistes. So

perhaps leave it be?

“C – YES. One thing to

consider, and maybe Nacho Areta has a thought on this one. But it seems to me

that it may be somewhat on the fence, but an argument could be made to lump Xanthopsar and Pseudoleistes, I do not recall which is the older name. In the

field they are quite different, and vocally they seem distinct. I think that a

good case can be made for retention of the two genera although their genetic

distance is much lower than various other genera in the family which are

considered as a single genus.”

Comments from Pacheco:

“A) YES, by recognition

of seven subfamilies.

“B) YES, by return to

pre-Short treatment.

“C) YES. Only missing in this sequence was mentioning Sturnella in second position. [now added]

Comments from Claramunt:

“A. NO.

Seven subfamilies is too much. Xanthocephalus and Dolichonyx would

fit fine into Sturnellinae (the grassland icterids), and Amblycercus fits

perfectly in Cacicinae; there is no need for erecting three additional

subfamilies with only one genus each. I think that using just four subfamilies

(Sturnellinae, Cacicinae, Icterinae, and Agelaiinae) would lead to a more

reasonable and elegant classification.

“B. YES.

Unnecessary, in my opinion, but fine. Leistes has been used a lot

in the XX century. Yellow versus red.

“C. YES.”

Additional comments from Remsen: “Concerning Santiago’s comment on A, I think that the number of

subfamilies should be dictated by the degree of branching deep in the

tree. In this case, there are seven

deep, old divisions in the family. If

all diversification was recent, then that pattern would suggest zero subfamilies

needed. If there were 15 separate

lineages near the origin of the family, then I’d go for 15. Etc.” Notice that

in the original paper, we outline our rationale for assigning subfamily ranks

based on comparable lineage age. I know

Daniel, for example, opposes new subfamily assignments until we have an

objective way for assigning these throughout.

In the paper, we attempt to provide this objectivity, and when

time-calibrated trees are available for other groups, the same rationale can be

applied to them.”

Comments from Areta: “A. YES. I am fine with the seven subfamily

treatment, although I also like Santiago´s suggestion of four subfamilies. Both

have their pros and cons. B-YES. I also agree in that this is not a necessary

move, but I like the separation between the red and the yellow meadowlarks.

C-YES.”

Comments from Cadena: “A. NO. Maybe I am the only one who feels this way, but

I must stress again that I see no point in recognizing subfamilies in our

classification unless (1) we come up with some sort of working definition of

what a subfamily is (hard, but could be done based on, say, age of clade) and

(2) we define subfamilies consistently across all families, not haphazardly as

it has been happenning so far (different arguments for different cases, many

families in which the issue is not discussed at all). Here in particular there

has been discussion about whether seven subfamilies is too many; without a

working criterion as to what subfamilies are, someone could also argue that

seven are too few and any decision would come down to subjective arguments. We

really need some consistent criteria. B. NO. Leistes and Sturnella are

sister groups, so there is no reason to change our classification bouncing back

to the older treatment; I think that changes at genus level and above should

only be done when strictly necessary (i.e. when groups are not monophyletic). I

see members voting because they like something better than something else –

this is hardly defensible while I think that maintaining stability whenever

possible is something we should really strive for C. YES.”

Comments from Stotz: “A. NO I realize that

I voted for this in NACC, but the comments of Daniel and Santiago have

crystallized a vague feeling I had that both committees have been very

inconsistent about the recognition of subfamilies. I think we do need to develop criteria for

recognizing these units.

B. YES This is a deep split and corresponds to a

clear plumage separation between the red-breasted and yellow-breasted meadowlarks.

C. YES Fits what we know

of the relationships among icterid genera.”

Additional

comment from Claramunt: “A comment on

the use of subfamilies. The “subfamily” is an auxiliary category. All birds

must be classified into the main categories (Genus, Family, Order), but the use

of auxiliary categories is optional (fide The Code). Therefore, it is perfectly

fine to have a classification in which some families are subdivided into

subfamilies and others are not. Subfamilies are useful for subdividing large

and diverse families like Icteridae, Furnariidae, and Tyrannidae, but we don't

need to erect subfamilies within Formicariidae or Melanopareiidae. In my

opinion, divergence times should not have a predominant role in assigning

taxonomic ranks. Given uncertainties regarding clade age estimates, it is

unnecessarily destabilizing to base decisions on particular thresholds. In my

opinion, subdividing families (and other main categories) is more a matter of

subdividing diversity (lineage and/or phenotypic) into groups that have a lot.”

Additional comments from Remsen: “Although an auxiliary category, subfamilies are widely

used in ornithology to acknowledge deep divergences within a family (itself an

utterly arbitrary category). Thus, there

is indeed a working definition for their use.

This is independent of the number of genera within a family. For example, avocets and stilts are widely

placed in separate families within Recurvirostridae, despite a minimal number

of genera and species. Subfamilies are

NOT just a tool to subdivide big families into more manageable units --- they

are independent of diversity. They add

information to the classification in terms of drawing attention to old lineages

within the arbitrary taxon category “family” that are nearly as old as the

family itself. In the Icteridae, the

seven lineages treated now by NACC as subfamilies are all lineages that have

been evolving separately since the late Miocene, and their recognition

qualitatively characterizes the signal from the time-calibrated phylogeny ….

Thus improving the qualitative information content of the classification and

drawing attention to hitherto unrecognized deep divergence, especially Xanthocephalus.

“If

there were just two species in the family, say Xanthocephalus xanthocephalus and Sturnella magna, in my opinion there

should be two subfamilies to acknowledge the ancient split, almost as old as

the family node. If there were just two

species Sturnella magna and Sturnella neglecta, then the branching

pattern would be very different, with two recently diverged lineages and no

subfamilies. The problem, obviously, is

where to draw the line on a continuous scale, such as time. Paleontologists use spikes in turnover rates

in the fossil record to place boundaries on the continuum, and so I think the

logical way to go is to use those independently defined boundaries in bird

classification to mark taxon boundaries.

In the Icteridae, estimates of the ages of the subfamily lineages are

all at least 8 mya, i.e. Miocene (5.3 to 23 mya).

“To

address Daniel’s point, the reason we can’t apply a subfamily definition across

all families is that we don’t have time-calibrated phylogenies for all

groups. That will be fixed soon.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

A. “YES” based upon the

deep branching patterns revealed in the tree.

I agree with Van that with an auxiliary category such as subfamily, we

shouldn’t be forced into a “one size fits all” definition, and, instead, let

the trees dictate when to recognize subfamilies or how many to recognize.

B. “YES. As Van points out, this is the deepest split

between any two genera or proposed genera in the tree, which should be

recognized at the generic level in my opinion.

It also conforms nicely to a yellow-breasted meadowlark versus

red-breasted meadowlark split, which better fits my concept of more narrowly

defined, morphologically coherent genera.

C. “YES.”