Proposal (780) to South

American Classification Committee

Change

the generic classification of the Trochilinae (part 1)

Two recent studies of the generic classification of

the Trochilini or “Emeralds” detected numerous instances of polyphyly and other

incongruences with respect to the DNA-based phylogeny of this group (Stiles et

al. 2017a, 2017b), the largest major clade of hummingbirds with over 100 species. The first study addressed problems of generic

nomenclature in the Trochilidae, with particular reference to the two of the

largest and most problematic genera, Amazilia

and Leucippus. The second paper

proposed a new generic classification of the Trochilini to bring it into the

best possible accord with the phylogeny of McGuire et al. (2014), which treated

275+ species, including most or all species in all of the ca. 30-35 currently

recognized genera. Our overall objective

was to produce a classification taking as its base the branching pattern of the

phylogeny, while preserving stability of existing nomenclature wherever

possible. We tried to produce cohesive, diagnosable genera while avoiding

producing large, undiagnosable genera on the one hand, and an excessive number

of small or monotypic genera on the other; this necessitated a rather more

flexible treatment of branch lengths. In

the process, we found numerous instances of homoplasy in plumage color and

pattern as well as discordance of plumages in other monophyletic

groupings. We have all been weaned on a

classification whose basis was to a very large extent on plumage, so the new

classification resulted in many drastic reallocations of generic circumscriptions:

this required the resurrection of nine generic names currently considered

synonyms, synonymizing seven currently recognized genera and the creation of

one new genus. We here present the new generic classification for review by the

SACC. This classification is presented in Figure 1 of Stiles et al. (2017b)

below, and as we work through this, we present our reasoning for each change in

brief; for further details regarding nomenclatural issues, see Stiles et al. 2017b.

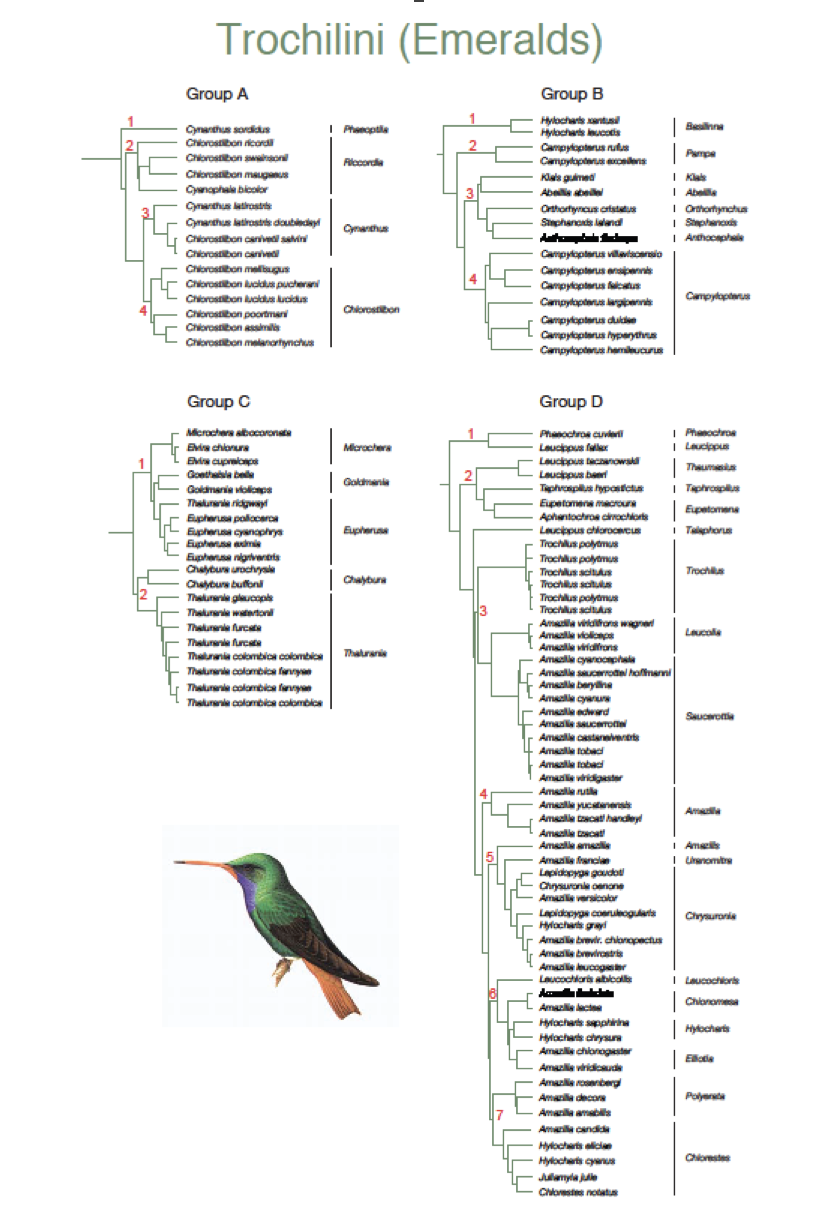

We began

by dividing the Trochilini into four large groups (A, B, C and D), within each

of which we recognized from two to seven subgroups, and further divided these

to produce new generic groupings. We found that many of these new groupings

showed strong geographical coherence, sometimes at odds with similarities in

plumages. In this proposal we treat groups A, B and C; a subsequent proposal

will deal with group D, by far the most difficult, including untangling the

chaos associated with the generic names Amazilia

and Leucippus.

Group A

includes the currently recognized genera Chlorostilbon,

Cyanophaia and Cynanthus. Given

that Cynanthus as currently

constituted includes the species sordidus,

one alternative would be to lump all the other genera into Cynanthus. We rejected this option because it would mask

considerable genetic and phenotypic diversity. Because sordidus is clearly an outlier (subgroup A1, sister to the rest of

group A), we advocate returning it to its status as the monotypic genus Phaeoptila (it had been lumped into Cynanthus without explanation by

Peters). Examining the remaining groupings, a broad Cynanthus includes two coherent subgroups of Chlorostilbon (subgroups A2 and A4), separated by Cynanthus itself (subgroup A3): in

effect, Chlorostilbon as a genus is

polyphyletic. Subgroup A2 includes

three species of the Greater Antilles and Cyanophaia

bicolor of the Lesser Antilles, the

most divergent in plumage; Subgroup A4 includes the Chlorostilbon species of southern Middle America and South America

including the type species, mellisugus.

We therefore advocate resurrecting the genus Riccordia for subgroup A2, and including within it Cyanophaia. We ascribe the greater

divergence in plumage of bicolor to

rapid evolution on isolated small islands: a similar case in the Polytminae is

the Lesser Antillean genera Eulampis

and Sericotes, which the phylogeny

found to be nested within Anthracothorax.

Cynanthus forms a compact generic group

A3, the surprise being that nested within it are three to five (depending upon how finely one splits

these taxa) species nearly always included in Chlorostilbon because of their plumages. Recognizing these as a

separate genus Chloanges is not

acceptable, as this would make Cynanthus itself

paraphyletic; we therefore include these species in Cynanthus. One conclusion is that the “typical” plumage of Chlorostilbon shows homoplasy; however,

another conclusion is that Cynanthus represents

a coherent biographical radiation in northern Middle America.

Group B

includes species in several genera. Subgroup B1 comprises two Mexican species

often included in Hylocharis in the

past, leucotis and xantusii. This is clearly untenable

because the type species of Hylocharis is

in Group D in the phylogeny. We therefore follow several recent authors in

placing these species in the genus Basilinna.

Subgroup B2 includes two Mexican species of Campylopterus,

separated from the rest of this genus by subgroup B3. We therefore advocate

resurrecting the generic name Pampa, as

used and diagnosed by Ridgway, for these species including as well its type

species, curvipennis, not included in

the phylogeny but close to (and sometimes lumped with) excellens, thus resolving the apparent polyphyly of Campylopterus.

Subgroup B3 includes

five small genera (Klais, Abeillia, Orthorhynchus, Anthocephala and Stephanoxis, all on long branches. One

alternative would be to lump all five into Orthorhynchus,

the oldest name. A second would be to lump Klais into Abeillia, and

the remaining three into Orthorhynchus. However, the lack of morphological or

biogeographic coherence among this group leads us to continue recognizing all

five genera, which also promotes stability.

Subgroup B4 includes the bulk of the genus Campylopterus including its type species largipennis, with species ranging from Middle America through much

of South America. Although some of the branch lengths are rather long, we see

nothing to be gained by splitting a well-diagnosable genus like Campylopterus into three or four small

genera, at least one of which would require a new genus name; we therefore

recommend continued recognition of a broad Campylopterus,

again preserving stability.

Group C

includes only two subgroups. Subgroup C1comprises two clades. The first is a

tight group of three species in two genera, Microchera

and Elvira, all of which inhabit

lower middle elevations of the mountains of Costa Rica and western Panamá.

Given the short branch lengths joining them, we consider that all are best

considered congeneric; Microchera has

priority. Microchera has long been

considered monotypic due to the very distinctive male plumage of albocoronata, however the female plumage

is quite similar to those of Elvira.

The

second clade breaks into two groups: the first comprises the monotypic genera Goldmania and Goethalsia of the Darien highlands of eastern Panama and adjacent

Colombia; the second includes Thalurania

ridgwayi and the several species of the genus Eupherusa. We see no reason for maintaining two monotypic genera in

the former group, and lump Goethalsia

into Goldmania, which has

priority. The two species are similar in

morphology and share an unusual type of undertail coverts, and differ only in

color patterns; they show a somewhat leapfrog-like pattern of distribution on

isolated mountaintops in the Darien. These two species are adjacent in all

recent classifications.

The

surprise in the second group is Thalurania

ridgwayi, which has always been included in this genus since its

description, based upon its green throat and chest, dark abdomen and bright

blue-violet crown. However, the genetic data preclude inclusion of ridgwayi in Thalurania; moreover, a closer examination of its plumage reveals

previously overlooked similarities in plumage with Eupherusa. Furthermore, its Pacific slope distribution accords much

better with that of Eupherusa than

that of Thalurania, which extends

northward in the Caribbean lowlands to Guatemala and only occupies the Pacific

slope from southwestern Costa Rica southwards into South America. Hence, we

advocate inclusion of ridgwayi in the

genus Eupherusa. The only other

option would require naming a new genus for ridgwayi,

which we deem unnecessary given its close genetic relationship to Eupherusa.

We now

present the following proposals for consideration by SACC. Although several of

these are most strictly in the domain of the NACC, we present them here because

they do affect the classification of some genera of South America as well.

1. [extralimital --- advisory only]

A. Expand the genus Cynanthus to

include Chlorostilbon sensu lato.

B.

Separate the species sordida in the

genus Phaeoptila; doing so then

permits further consideration of the circumscription of Chlorostilbon. We strongly favor this option.

2. [extralimital --- advisory only]

A. Restrict Cynanthus

to exclude the canivetii group of

species of Chlorostilbon, segregating

these in the genus Chloanges.

B.

Include the aforementioned species in Cynanthus.

We favor this option because option A would render Cynanthus paraphyletic.

3. [extralimital --- advisory only]

A. Retain the Antillean species in Chlorostilbon.

B.

Split Chlorostilbon into two genera,

reviving the generic name Riccordia for

the Antillean species including Cyanophaia,

with the second genus including the majority of the species of Chlorostilbon including its type

species; nearly all of these species are South American. We strongly favor this

option, because option A would produce a polyphyletic Chlorostilbon.

4. [extralimital --- advisory only]

A. Retain the species excellens and

its close relatives in the genus Campylopterus.

B.

Split Campylopterus into two genera,

reviving Pampa for the aforementioned

northern species excellens and its

relatives of Mexico and Guatemala. We

strongly favor this option because option A would render Campylopterus polyphyletic.

5. A. Retain the non-Pampa species

of Campylopterus in this genus, which

includes its type species.

B.

Split the restricted Campylopterus into

three or four small genera. In this case, we favor option A, especially as at

least one new generic name might be required for option B, and Campylopterus as restricted is well

diagnosable.

6. A. Retain generic rank for Orthorhynchus,

Abeillia, Klais, Anthocephala and Stephanoxis.

B. Lump all of these

genera into Orthorhynchus.

C.

Lump the first two genera into Abeillia and

the last three into Orthorhynchus.

Here we favor option A because all of these genera are separated on long

branches, and the because of the lack of morphological or biogeographical

concordance between them.

7. [extralimital --- advisory only]

A.

Continue to recognize Microchera and Elvira as separate genera.

B.

Lump Elvira into Microchera. We favor this option because of biogeographical

concordance, short branch lengths and previously overlooked similarities in

female plumages.

8. A. Continue to recognize Goethalsia

and Goldmania as separate genera.

B. Lump Goethalsia into Goldmania. Here

also, we favor this option as the two species are similar morphologically and

biogeographically, the difference between them being only coloration,

especially of the males.

9. [extralimital --- advisory only]

A. Name a new genus for “Thalurania”

ridgwayi, because the genetic data

preclude its inclusion in Thalurania.

B. Include ridgwayi in the genus Eupherusa

reflecting hitherto overlooked similarities in plumage, biogeographical

concordance and genetic proximity. We favor this option.

10. A. Continue to

recognize the genera Thalurania and Chalybura.

B.

Lump Chalybura into Thalurania, which are sister genera in

the phylogeny. We favor option A. Although sharing a few similarities in

plumage, these genera are separated on long branches and are well diagnosable

from each other.

References (downloads available

at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/J_Remsen):

McGuire, J. A., C. C.

Witt, J. V. Remsen, Jr., A. Corl, D. L. Rabosky, D. L. Altshuler, & R. Dudley. 2014.

Molecular phylogenetics and the diversification of hummingbirds. Current Biology 24: 1-7.

Stiles,

F. G., V. de Q. Piacentini, & J. V. Remsen, Jr. 2017. A brief

history of the generic classification of the Trochilini (Aves: Trochilidae):

the chaos of the past and problems to be resolved. Zootaxa 4269: 396–412.

Stiles, F.

G., J. V. Remsen, Jr., & J. A. McGuire.

2017. The generic classification

of the Trochilini (Aves: Trochilidae): reconciling classification with

phylogeny. Zootaxa 4353: 401-424.

Gary Stiles, March 2018

__________________________________________________________

Comments from Jaramillo: “9

A – Yes, B – No. It seems more informative to put ridgwayi in a new genus.”

Comments

from Areta: “I vote YES on the following: 1B, 2B, 3B, 4B, 5A, 6A

(However, it may well be the case that lumping all these species into a single

genus Orthorhynchus will result in finding

deeper homologies than hitherto acknowledged) 7B, 8B, 9B (This is striking, as ridgwayi does look remarkably like traditional Thalurania species! If someone erects a new genus

for this, please don´t use “Pseudothalurania”!),

10A

Comments from Claramunt: “1-3 “Group A” is very uniform phenotypically and

is not excessively species-rich or old, so I don’t see the rationale for a

solution that involves more genera instead of fewer. The resultant genera would

not be diagnosable. So, I vote YES for an expanded Cynanthus (Yes to 1A

and 2B, and NO to all other alternatives).

“6C. guimeti

and abeillei seem to form a

superspecies rather than two different genera, so lump into Abeillia. Anthocephala is distinct, but the similarity between Orthorhyncus and Stephanoxis is striking. So, two genera instead of five.

“7A. Microchera is strikingly diagnosable, one of the most distinctive

hummingbird genera.

“8B. Yes to lump these two together. I also

think that they could be merged into Eupherusa.

10A Yes to maintain Chalybura and Thalurania

since there is no phylogenetic reason to change things here. But I don’t

strongly oppose a potential lumping.

Comments from Zimmer:

“1B. YES. This would be

the logical path based upon the genetic data.

“2B. YES. Chlorostilbon, as currently constituted,

is polyphyletic, so something has to be done with the canivetii-group. As Gary

points out, isolating the canivetii-group

in the genus Chloanges

would render Cynanthus paraphyletic,

so, including these species in an expanded Cynanthus

would appear to be the only solution.

“3B. YES. This is

mandated by the genetic data, and results in two biogeographically coherent

genera.

“4B. YES. This change

is clearly mandated by the genetic data.

Retaining excellens & rufus in

Campylopterus would render the genus

polyphyletic.

“5A. YES. Based upon

the length of some of the branch lengths within this species-cluster, one could

make a case for recognition of multiple genera.

But, when considering morphology, the broader Campylopterus, as seen in Subgroup B4, really seems like a pretty

cohesive, readily diagnosable group, so my inclination is to keep them

together.

“6A. YES. Any course

other than retaining the status quo would result in some groupings that would

be hard to defend on either morphological or biogeographical grounds, and

looking at the branch lengths separating these genera, I don’t think the

genetic data points strongly in that direction anyway.

“7B. YES. Based simply

upon the genetic data, we could go either way on this, but lumping them into

one genus makes perfect sense on distribution, ecology, biometrics, and female

plumage, and thus, is more informative of relationships than would be

maintaining the current arrangement, based solely upon the rather different

male plumage of the Snowcap.

“8B. YES. This option

makes perfect sense on biogeographical and morphological grounds.

“9A. I have to go

against the grain on this one. It’s

clear from the phylogeny that we can’t continue to treat ridgwayi in Thalurania. But other than a close genetic distance to Eupherusa, I really don’t see it

belonging there. Minus ridgwayi, Eupherusa is a tight-knit, coherent group (all still more closely

related to one another than to ridgwayi), all members of which have a similar

tail pattern and show prominent rufous in the wing. As far as I know, all of them, with the

possible exception of cyanophrys, are

also more montane (middle-elevation) in their distribution and habitat

preferences, as opposed to ridgwayi,

which occurs mostly below or at the lower end of the elevational distribution

of Eupherusa. I think ridgwayi

is simply an oddball, closest genetically to Eupherusa, but morphologically, highly suggestive of Thalurania. The proposal doesn’t spell out what the

“hitherto overlooked plumage similarities” of ridgwayi to Eupherusa

are, but I am curious, since they aren’t at all evident to me. This strikes me as a very different situation

from Microchera and Elvira, where genetic distances were

similar to those in the present case, but the only real disparity was in the

male plumage of one species, whereas biometrics, female plumage, ecology and distribution

were all pointed toward inclusion in a single genus.

“10A. YES.

Absolutely. I would be strongly opposed

to lumping these two morphologically and ecologically distinctive genera, and

given the branch lengths, I don’t think the genetic distances point in that

direction either.”