Proposal

(781) to South American Classification Committee

Change the generic classification of the

Trochilinae (part 2)

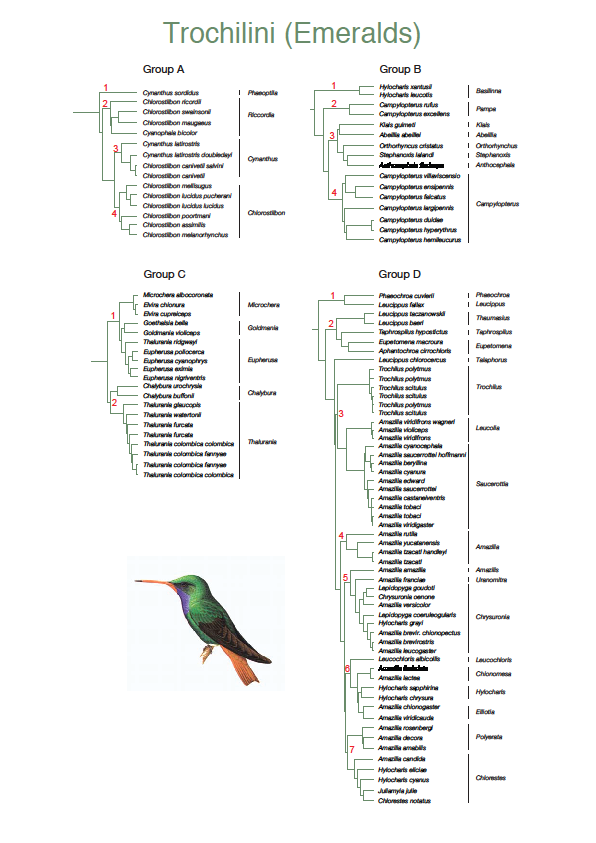

The

genetic tree of the Trochilidae by McGuire et al. (2014) showed that the

generic taxonomy of the hummingbirds was incongruent with phylogeny at many

points, and that the tribe Trochilini, popularly known as the Emeralds,

epitomized this conflict. The bewildering array of problems to be resolved was

summarized briefly by Stiles et al. (2071a), and a resolution of these in a new

generic taxonomy was presented by Stiles et al. (2017b). Based upon the genetic

tree, we divided the Trochilini into four groups. In part 1 of this proposal,

we treated Groups A, B and C; this proposal deals with the largest and

difficult group of genera, Group D. We divided this group into seven subgroups,

within each of which we recognize from one to four genera. The nomenclatural

issues are more complicated in this group, and for more detail and explanation

of our resolution of these, see Stiles et al. (2017a and 2017b). As in part 1, we work through the groups in

the order in which they appear in the figure, reproduced below.

Subgroup D1 includes only two genera, Leucippus and Phaeochroa, separated on long

branches. Recent classifications

of Leucippus have included several

other species, but the phylogeny places all of these in different subgroups,

leaving fallax, its type species,

alone in what becomes a monotypic genus.

Both occur in dry habitats, Phaeochroa

mainly on the Pacific slope of Middle America and northern Caribbean Colombia, L. fallax in dry to desertic habitats in

extreme northern Colombia and Venezuela. Phaeochroa

is also monotypic in most classifications, with cuvierii as its type, although some would split roberti of the Caribbean slope of Middle

America as a separate species. Both fallax

and cuvierii are rather

dull-colored but they differ in pattern: fallax

is uniform buff below, whereas cuvierii is

mostly green below, speckled or scaled with buffy-whitish; cuvierii is much larger, and the outer primaries are flattened and

thickened much like those of Campylopterus

in group B; indeed, Schuchmann include cuvierii

in Campylopterus for this reason.

However, this course is refuted by the phylogeny: the “sabre” wings of each

were derived independently. We advocate recognizing both of these as monotypic

genera.

Subgroup D2 includes two well-separated

clades. The first includes two species formerly included in Leucippus in recent taxonomies, taczanowskii and baeri. The phylogeny precludes their inclusion in Leucippus, but the generic name Thaumasius is applicable, its type

species being taczanowskii. These two

species share a rather dull, brownish plumage, differing in pattern and size,

but both occupy relatively dry habitats of the Pacific slope of extreme

southern Ecuador and northern Peru. The second clade includes three species on

long branches, currently segregated in three monotypic genera: Taphrospilus hypostictus, Eupetomena

macroura and Aphantochroa

cirrochloris. In plumage, hypostictus

and cirrochloris are dull in

coloration although differing in pattern; macroura

is very different in plumage, dark blue with a longer, forked tail. However, cirrochloris and macroura are sister species sharing a similar pattern of

distribution in lowland southeastern South America as well as “saber” wings

resembling those of Campylopterus in

the males, whereas hypostictus

occupies mainly subtropical elevations along eastern Andean slopes from

southern Colombia to northern Bolivia, and lacks the modified primaries of the

other two. This species has been included in Leucippus by some authors, but the phylogeny precludes this

treatment. Here, three options are available: a) lump all three in a single

genus, for which Eupetomena takes

priority; b) lump Aphantochroa and Eupetomena because of their sister

status, shared distribution and modified primaries in males, while maintaining

a monospecific Taphrospilus or c)

maintain three monospecific genera. We consider a) the worst option because it

gives no information regarding relationships and

would

subsume considerable genetic differences; option c), while preserving

stability, also ignores relationships among these species. We therefore prefer

option b), which is most informative in this respect as well as in distribution

and morphology, although its two species are widely divergent in plumage color.

However, such “color clashes” also occur in several other subgroups in group D,

as detailed below.

Subgroup D3 first includes a clear

outlier with no close relatives, “Leucippus”

chlorocercus, (it could even be

considered a subgroup by itself), which therefore requires its separation in a

monotypic genus Talaphorus, which was

originally described for it. Its distribution, along the upper reaches of large

Amazonian rivers, is also unique. Its inclusion in Leucippus in the past was due to its dull colors and conservative

plumage evolution having masked its genetic distinctiveness. Next in this

subgroup is a distinct clade including only the genus Trochilus with one or two species. Unique in morphology and

distribution, Trochilus clearly

merits generic rank.

Next in subgroup D3 are two

well-separated clades formerly included in Amazilia

(but such inclusion is refuted by the phylogeny; see below). The first

clade comprises three Mexican species: violiceps,

wagneri and viridicauda, for

which the generic name Leucolia is

applicable. We note here that we had accepted viridicauda as its type following the recommendation of Elliot, but

this was incorrect because it was described after Leucolia was named; we have submitted a manuscript (Stiles et all,

submitted) substituting violiceps as

the type species to correct this error. The final clade in D3 includes ten

species in two compact clusters separated by a very short branch, such that they all should be

considered as a single genus Saucerottia.

The four species of the first cluster are Middle American, the six of the

second cluster occur from southern Middle America into northern South America;

all share certain morphological features and glittering green over the chest or

the entire underparts. In the past, Saucerottia

had often been considered a subgenus within Amazilia, but generic status is supported by the phylogeny.

Subgroup D4 includes only three

species: rutila, yucatanensis and tzacatl; because the first is the type

species of Amazilia, these three

constitute the necessarily much-restricted genus Amazilia. The genetic distinctness of this subgroup was not

recognized heretofore due to numerous convergences in plumage with species of

several other subgroups.

Subgroup D5 includes two successive

outliers on relatively long branches, then two much more closely related

clusters of three and five species. The first outlier is the species amazilia,

often considered the type species of the genus Amazilia in the past, but the genetic tree does not support its

inclusion therein. We have proposed that the earliest generic name for this

species is Amazilis (see Stiles et

al. (2017a) regarding the nomenclatural complexities involved). This species

appears to be an old isolate at the southwestern extreme of the distribution of

what we dubbed the “amazilian complex”, and it also has a unique plumage

pattern. The second outlier, on a slightly shorter branch, is “Amazilia” franciae, which we also consider to constitute a separate genus,

for which the name Uranomitra is

applicable. It is the only member of the complex with a montane distribution

and marked sexual dichromatism, as well as several morphological differences

from others in this complex.

The third group of species in subgroup D5 provides the most extreme mismatch between the genetic data and plumage features. The first cluster includes three species currently placed in three genera: Chrysuronia oenone, Leucippus goudoti and Amazilia versicolor; the second, four species in three genera: Leucippus coeruleogularis, Hylocharis grayi, Amazilia brevirostris (usually including chionopectus) and A. leucogaster. The white-bellied species versicolor, brevirostris and leucogaster were included in Agyrtria by Schuchmann (1999), but Agyrtrina is correct. Two options exist here: a) give each cluster a separate generic name; or b) combine both clusters in a single genus. For the first option, the generic name Chrysuronia has priority; for the second, Eucephala (the original genus name of grayi). For the second option, Chrysuronia takes priority over Eucephala. We favor the second option because of the short branch connecting the two clusters, and the enlarged genus Chrysuronia is scarcely more heterogeneous in plumages than either cluster produced by the first; in addition, option b combines in the same genus members of two genera that must disappear in the interest of priority, Agyrtrina and Lepidopyga. The two most divergent species in male plumage, “Lepidopyga” goudoti and coeruleogularis, are not even sisters in the phylogeny, and the “Agyrtrina” species also appear in both clusters. The females of all of these species are more or less “white-bellied”, as are the males in the monomorphic species.

In subgroup D6, the species albicollis is an outlier on a long

branch, and we favor continuing to recognize its distinctness by maintaining it

in the monospecific genus Leucochloris;

its plumage is also unique. The second cluster in this subgroup, on a fairly

long branch, includes two species: “Amazilia”

lactea and fimbriata, which share a similar plumage pattern, differing merely

in colors. The phylogeny precludes their inclusion in Amazilia, and for them, the generic name Chionomesa is available and applicable. Both species are widely

distributed in lowland cis-Andean South America, fimbriata more northern, lactea

more southeastern in ranges. We favor placing both in Chionomesa. The third and similarly distinct cluster in subgroup D6

includes the species sapphirina and chrysura, which we consider should

constitute the restricted genus Hylocharis,

of which sapphirina is the type

species. These share a unique plumage feature and both occur in southeastern

South America, although sapphirina has

a broad but disjunct range in South America north of the Amazonian watershed.

The fourth cluster in subgroup D6

includes two species previously placed in either Leucippus or Amazilia: chionopectus and viridicauda. These species are less distinct genetically from the

preceding cluster, such that they could be included in Hylocharis, but they are widely discordant in distribution and

ecology, being found at middle and upper elevations in the Andes of Peru and

Bolivia, such that we consider them to best represent a distinct genus. Their

distinctiveness had previously been suggested by Peters, but neither he nor we

found a generic name applicable to them. We therefore proposed a new genus Elliotia for them. Unfortunately, this

name was found to be preoccupied, and we have submitted a manuscript

substituting another name. We therefore suggest to SACC members that they

evaluate the evidence for generic status of these two species under the generic

name yet to be published.

Subgroup D7 includes two genetically

distinct clusters. The first contains the species “Amazilia” amabilis, decora and

rosenbergi. For these, the generic

name Polyerata is applicable, with amabilis as its type species. The

circumscription of this genus by some recent authors included several other

species that the phylogeny placed in other subgroups, but Polyerata as here restricted is clearly valid, and we advocate its

recognition. The second subgroup includes five species arranged in a stepwise

cascade with short branches separating them: “Amazilia” candida, “Hylocharis” eliciae, “Hylocharis” cyanus, Juliamyia julie and Chlorestes

notatus. Inclusion of any of these species in Amazilia or Hylocharis is

not supported by the phylogeny. Because all of the branch lengths are short, we

consider that any further subdivision of this group would be arbitrary and

could require the resurrection of at least one generic name and the probable

erection of one new genus, we prefer considering all of these species

congeners; the generic name Chlorestes takes

priority. Thus, the generic name Juliamyia

is placed in synonymy: in fact, the two most closely related species are notatus and julie, which differ considerably in male plumages but share one

unique feature, their strongly rounded tails. Once again, in this group as a

whole, female plumages are much more similar than those of the males, and that

of the one monomorphic species, candida,

also fits the situation in the enlarged Chrysuronia

above.

Finally, we leave two Middle American

species unclassified (incertae sedis)

because we lack genetic information for them and are reluctant to place them on

the basis of plumage characters that have been repeatedly shown to exhibit

homoplasy: “Amazilia” luciae and “Amazilia” boucardi.

We

now present the results of this generic rearrangement for valuation by the SACC

in the following series of proposals.

1. A. Consider subgroup D1as a single genus, for which Leucippus takes priority.

B. Recognize Leucippus and Phaeochroa as

distinct monospecific genera. Given the long branches and morphological

distinctiveness, we strongly favor this alternative.

2.

A. Maintain baeri and taczanowskii in

Leucippus.

B. Recognize the genus Thaumasius for these two species. We strongly favor this option,

because option A would produce a polyphyletic Leucippus.

3. A. Continue to recognize three monospecific

genera Aphantochroa, Eupetomena and Taphrospilus.

B. Lump Aphantochroa

into Eupetomena while maintaining

a monospecific Taphrospilus.

C. Lump all three into a single genus Eupetomena. We favor option B as being

most concordant regarding relationships, morphology and distributions, although

cirrochloris and macroura differ strongly in plumage; we consider option C as the

worst alternative.

4. A. Recognize the monospecific genus Talaphorus for chlorocercus.

Given its great genetic distinctness, there really is no other sensible option

here.

5. . [extralimital ---

advisory only] A. Recognize the genus Leucolia for the extralimital

species viridifrons, violiceps, and wagneri. Again, there is no real alternative: they

cannot remain in Amazilia, no other

generic name previously applied for them accords with the genetic tree and they

share a characteristic distribution.

6. A. Split the genus Saucerottia

into two genera, one Middle American and the other found from southern

Middle America into South America.

B. Maintain a single genus Saucerottia including both groups above. We strongly favor this

option given the close relationships and morphological congruence of these two

groups.

7. A. Restrict the genus Amazilia to the species in subgroup D4.

B. Continue to recognize a broader Amazilia, although its limits would be

difficult to define and would subsume too much genetic divergence. We strongly

favor option A.

8. A. Recognize the genus Amazilis as a monospecific genus for the species amazilia based upon its distinctness

genetically and in plumage and distribution.

B. Include more of subgroup D5 in Amazilis. We favor option A.

9. A. Recognize the monospecific genus Uranomitra for the species franciae, given that it is so distinct

genetically, morphologically and in its highland distribution from the

following species cluster.

B. Include franciae

and the following group in Amazilis.

This option would produce a very heterogeneous group subsuming a great deal of

genetic, morphological and distributional diversity. We favor option A.

10. A. Divide the remaining ten species of

group D5 into two genera, Chrysuronia and

Eucephala.

B. Include all eight species in the genus Chrysuronia. Although decidedly

heterogeneous in male plumages, the combined group is little more so than each

of them separately, the groups are closely related and this option would

include members of two genera that must be sunk due to phylogeny but are not

sisters in the phylogeny. We favor option B.

11. A. Continue to separate albicollis in a monospecific genus

recognizing its genetic distinctiveness and unique plumage. We favor this

option, because option B would subsume much genetic and distributional

divergence.

B. Combine Leucochloris

with one or more clusters of

subgroup D6.

12. A. Recognize Chionomesa for the species fimbriata

and lactea. We favor option A,

because the other subgroups are approximately equal in genetic distinctiveness

and differ greatly in distribution.

B. Combine these with one or more clusters in

subgroup B6.

13. A. Recognize a restricted Hylocharis for the species sapphirina and chrysura. All other species previously included in this genus fall

out in different parts of the phylogeny, and the genus as here restricted shows

a unique plumage feature and a largely congruent distribution.

B. Include at least the following group in Hylocharis reflecting genetic

similarity. We favor option A, for the reasons given more fully below.

14. A. Recognize a new genus for the species chionogaster and viridicauda (here called Elliotia,

but this is preoccupied; its name to be supplied in a manuscript

submitted).

B. Include these species in Hylocharis. We favor option A, because

option B would produce a morphologically, ecologically and biogeographically

incoherent grouping.

15. A. Recognize a restricted genus Polyerata for the species

amabilis, extralimital decora, and rosenbergi.

This proposal is novel only in its restriction; the inclusion of several

other species in some classifications is precluded by the genetic data,

although we also do not include two species for lack of genetic data (see

below). There is no really feasible alternative here.

16. A. Divide the remaining cluster in subgroup D7 into two

to four genera.

B. Consider the five species in this cluster

congeneric under the name Chlorestes. We

favor this option because these species occur in a stepwise cascade with very short branches between them,

such that any such subdivision would be arbitrary and would require at least

one new generic name.

Gary Stiles, March 2018

__________________________________________________________

Comments

from Areta:

“I vote YES on the following: 1B, 2A, 3B, 4A, 5A, 6B, 7A, 8A, 9A, 10B, 11A, 12A, 13A, 14A, 15A, 16B

Comments

from Zimmer:

“1B. YES. The branch

lengths in the tree and the morphological/ecological distinctions between fallax and cuvierii would argue against treating them together in a restricted

Leucippus. That Phaeochroa

did not cluster with Campylopterus or,

particularly, with Aphantochroa (with

which there are numerous behavioral as well as morphological parallels) is one

of many surprises (to me) revealed by the phylogeny.

“2B. YES. Any other

treatment would leave us with a polyphyletic Leucippus.

“3B. YES. This one

pains me! It’s difficult to reconcile

the plumage distinctions between the colorful, long/deeply fork-tailed macroura and the drab, almost

featureless cirrochloris, enough to

consider them in the same genus.

However, they are clearly sister species in the phylogeny; they share a

similar geographic distribution (which the phylogeny reveals to be more

important than plumage differences or similarities in several cases); both have

the “sabrewing” morphology found in Campylopterus;

and both are persistently vocal, aggressive birds that assume prominent perches

and routinely bully other hummingbirds at feeders. That’s enough to nudge me over the line in

favor of lumping Aphantochroa into Eupetomena, which has priority. My second choice would be to maintain all

three species in monotypic genera, but, as Gary points out, that configuration

would not be informative regarding the sister relationship of macroura and cirrochloris. I have no appetite for lumping Taphrospilus in with the other two

species.

“4A. YES. This is the

only option given the genetic distance and branching patterns reflected in the

tree. On morphology and its restriction

to scrubby habitats, I would have guessed chlorocercus

to be closer to Thaumasius (baeri and taczanowskii). But, as is

the case with L. fallax, biogeography

and narrow habitat specialization prove to be more important clues to genetic

relatedness than plumage.

“5A. YES. This is the

only option given the relationships shown in the phylogeny, and makes sense

biogeographically. I assume that the

three species we are talking about recognizing in Leucolia are violiceps,

wagneri and viridifrons (from which wagneri

is a split), NOT viridicauda or viridigaster (neither of which have

Mexican/Middle American distributions) as cited in different parts of the

Proposal. The tree correctly includes viridifrons.

“6B. YES. Hairsplitting

in my opinion, to attempt to separate these 10 species into different genera.

“7A. YES. I think this

greatly restricted version of Amazilia

makes more sense genetically and biogeographically than the expansive

alternative.

“8A. YES. I strongly

favor this option. Lumping all of

subgroup D5 into Amazilis would make

for a very heterogeneous, difficult to diagnose genus.

“9A. YES. Genetics and

distribution favor this approach, in my opinion.

“10B .YES. Both options

leave us with groupings that are genetically cohesive, but difficult to

diagnose on plumage, and I don’t see the genetic distance between the two

clusters, nor the slightly greater morphological heterogeneity introduced by

lumping the two clusters together as obstacles to treating them all in an

expanded Chrysuronia.

“11A. YES. Leucochloris albicollis is distinct

genetically, and in plumage, and, has a geographic distribution restricted to

the greater Atlantic Forest & temperate forest biome of southeastern

SA. It is also noteworthy for its

far-carrying, distinctive, and incessantly delivered songs. I can’t see lumping it in with other members

of the subgroup D6. The wording in this

sub-proposal suggests a preference for Option B, but I don’t think that is what

Gary intended.

“12A. YES. This (fimbriata and lactea) form a genetically and morphologically cohesive pair, and

any other arrangement within this subgroup would contain too much heterogeneity

for my tastes.

“13A. YES. One of many

surprises (for me) revealed by the phylogeny, was the polyphyletic nature of Hylocharis. The bill morphology (with the laterally

expanded base) and color pattern (bright red with dark tip) shared by all of

the species in the genus (as currently constituted) made for a pretty

distinctive grouping. However, Cynanthus latirostris, Hylocharis/Basilinna leucotis and H./B. xantusii have similar bills, and

those species are nowhere close to sapphirina,

cyanus, chrysura, grayi/humboldtii or eliciae

in the phylogeny. I would also note,

that, in addition to being united by some plumage features, H. sapphirina and H. chrysura differ from eliciae

and cyanus in their vocal

behavior. It has always been my

impression that eliciae and (perhaps

to a lesser extent) cyanus males form

exploded leks to sing (and the vocalizations are somewhat similar as well),

whereas I have never observed any obvious lekking behavior in sapphirina or chrysura. At any rate, I

would strongly oppose lumping any other members of subgroup D6 into a reconstituted

Hylocharis with sapphirina and chrysura.

“14A. YES. Including

these two species within a pared-down Hylocharis

(to the exclusion of several morphologically similar species formerly included

in that genus) would be unpalatable to me, even if acceptable on genetic

distances alone.

“15A. YES. For reasons

spelled out in the Proposal.

“16A. YES. I would

favor recognizing two genera here: one

with the plumage outlier and sexually

monomorphic candida, and an expanded Chlorestes containing notatus, julie, eliciae, and cyanus.

“A.” candida appears to be

more different genetically from the rest of the group, it is the only sexually

monomorphic species in the bunch, the only one in which the male is relatively

dull in plumage, and, the only one of the bunch whose distribution is entirely

within Middle/Central America. Treating

them all in a single genus is certainly defensible on genetic grounds, but,

given a choice, I would prefer a more morphologically cohesive grouping.”

Comments by Claramunt:

“3A. Tempting to try to get rid of one monospecific genus but

divergence is so great between Eupetomena and Aphantochroa.

“5. No. The obvious alternative is to include these two species into Saucerottia,

given that the similar looking cyanocephala is in that clade

“8.B, 9.B. Separating amazilia

and franciae into monotypic genera would not prevent the remaining

clade to be heterogeneous (both amazilia and franciae were

included in the same genus, Amazilia, suggesting that they are not very

distinctive.

The risk with the following proposed changes is that

some are based on flimsy phylogenetic evidence (low node support).

“’I’m on the fence regarding the Hylocharis clade. I think

it could be perfectly fine to have a diverse Hylocharis, from fimbriata

to viridicauda in which color variation follows Gloger’s rule. Just

for lack of a strong conviction, I’ll go with the recommendation:12.A, 13A, 14A

15A.

Recognize a restricted genus Polyerata. On the edge in this one. They

could be included in Chlorestes instead of their own genus. But since a

sister relationship is not well-supported, the use of Polyerata may be a

solution for now.