Proposal (784) to South American Classification Committee

Split Grallaricula leymebambae from G.

ferrugineipectus

This

proposal is based on excerpts from the following paper. Where mentioned, figure

and table numbers are kept the same as in the paper for ease of reference to

the publication.

Van Doren BM,

Freeman BG, Aristizábal N, Alvarez-R M, Perez-Emán J, Cuervo AM, Bravo GA.

2018. Species limits in the Rusty-breasted Antpitta (Grallaricula

ferrugineipectus) complex. Wilson Journal of Ornithology. doi:

10.1676/16-126.1.

Background

The

Rusty-breasted Antpitta (Grallaricula

ferrugineipectus) is a small antpitta in the family Grallariidae

distributed from Venezuela to Bolivia. Three subspecies are currently

recognized, each of which inhabits a distinct montane region: G. f. ferrugineipectus is found in

northern and western Venezuela and the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta in adjacent

northern Colombia; G. f. rara in the

Eastern Andes of Colombia and the Sierra de Perijá, which straddles the

Colombia-Venezuela border; and G. f.

leymebambae in the Andean foothills from extreme southern Ecuador to

western Bolivia.

Current

knowledge of the distribution of the species has been improved by recent

discoveries of populations outside its traditionally known range. Although its

presence in Peru north of the Marañón River had been documented since the

mid-1950s based on 2 specimens taken independently by M. Koepcke and T. A.

Parker in Cancheque, Piura (Schulenberg and Parker

1981, Parker et al. 1985), there are now recent

records in the departments of Piura (Vellinga et al. 2004) and Lambayeque (Angulo Pratolongo et

al. 2012), as well as in the

Ecuadorian provinces of Loja and Pichincha (Athanas and Greenfield

2016; P. Coopmans, ornithologist, unpubl. data, collected 1994-2003). Likewise, only in the early 1980s was the species first

recorded in Bolivia (Schulenberg and Remsen

1982). More recently, MAR

and collaborators discovered a population in the Cauca Valley of the Central

Andes in the department of Caldas, Colombia that seems to be geographically

isolated from other conspecific populations. Taxonomic affinities of these

populations have never been formally assessed, and their taxonomic treatment

has been assumed to correspond to that of the geographically closest

populations.

Populations

differ somewhat in elevational distribution and habitat; subspecies rara and ferrugineipectus inhabit forested foothills from ~250 to 2200 m

asl. (Krabbe and Schulenberg

2003), and the Cauca Valley

antpittas are currently known only from one locality at 1000–1100 m asl.

Hereafter, these 3 populations will be referred to as the northern group. By

contrast, birds belonging to the southern group (populations from Ecuador,

Peru, and Bolivia) range substantially higher and inhabit montane forest from

1750 to 3350 m asl. (Ridgely and Tudor

2009). Southern group birds

seem closely tied to bamboo in the genus Chusquea

(Fjeldså and Krabbe

1990, Athanas and Greenfield 2016). This habitat association has not been documented for the

northern group, which can tolerate some degree of habitat degradation (Hilty and Brown 1986,

Niklison et al. 2008, N. Athanas, Tropical Birding Tours, 2017, pers. comm.).

The

3 subspecies of G. ferrugineipectus

were described based on differences in plumage and morphology. The subspecies

rara is the most divergent with respect to plumage, with a rich

rufous-brown underside and clear rufous tones on the crown and face, in

contrast to the dark brown to slate-brown upperside and rufous underside of

subspecies ferrugineipectus and leymebambae. These latter 2

subspecies both lack rufous on the

head, have duller underparts, and show an obvious white throat crescent; G. f. leymebambae differs from G. f. ferrugineipectus in larger size and darker overall coloration (Greeney 2013). Songs of the species also vary across its geographic

range. Most noticeably, G. f. leymebambae

gives slower and higher-pitched songs than G.

f. ferrugineipectus (Krabbe and Schulenberg

2003). The song of G. f. rara is poorly known and not

described in recent reference volumes (Krabbe and Schulenberg

2003, Greeney 2013). Finally, recordings

from northwest Ecuador demonstrate that this population’s songs seem slower

than those of other populations (e.g., see XC35333 on xeno-canto.org).

Because

populations of G. ferrugineipectus

are distributed allopatrically throughout the tropical mountains of northern

South America, reproductive isolation between subspecies cannot be directly

assessed. Early on, systematists proposed arrangements of species-level

taxonomy based on plumage differentiation within this complex. For example, G. f. rara was originally described as a

species because of its distinctive plumage (Hellmayr and Madarász

1914), while G. f. leymebambae was first described as

a subspecies (Carriker 1933). More recently, differences in distribution, morphology,

and vocalizations between G. f.

leymebambae and the northern group have led some authors (e.g., Ridgely and

Tudor 2009, BirdLife International 2017) to classify it as

a distinct species; however, no formal comparative analysis had systematically

examined genetic, vocal, and morphological variation within this complex.

New Information

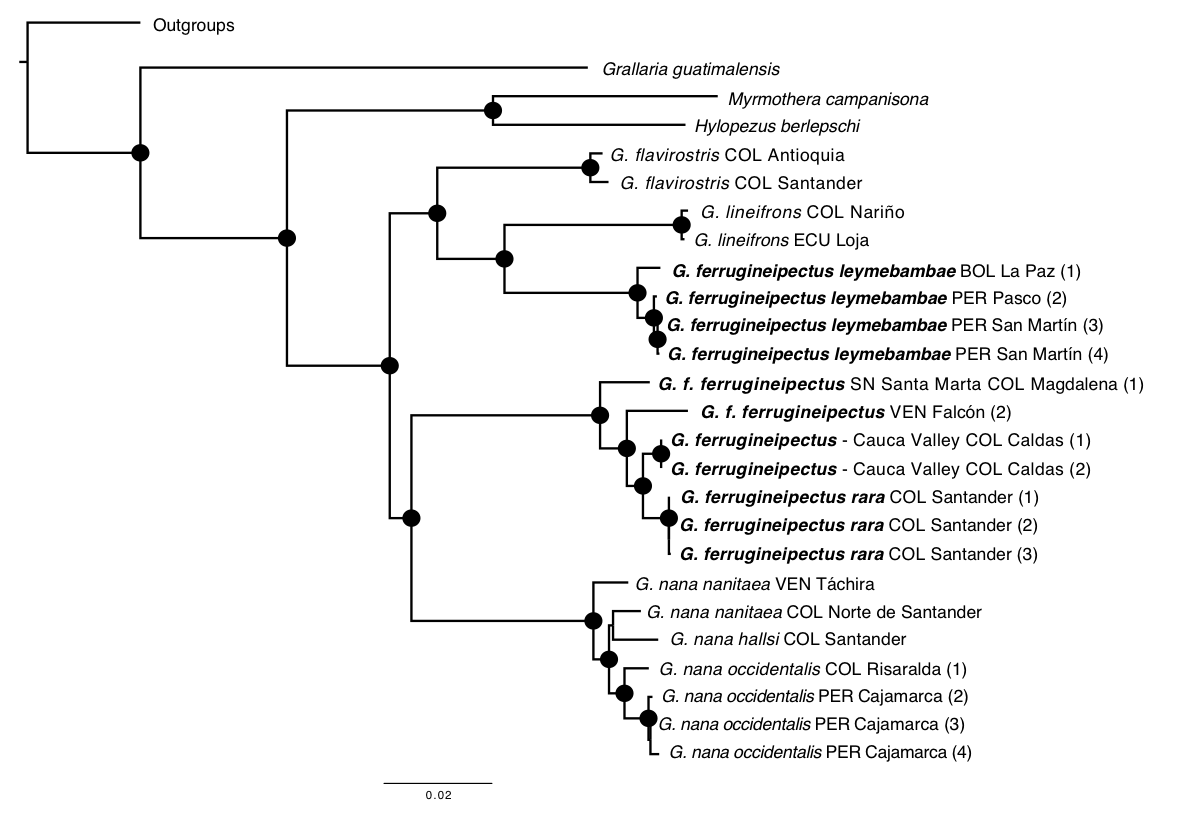

Maximum-likelihood

and Bayesian analyses produced identical topologies supporting the

non-monophyly of Grallaricula

ferrugineipectus. Northern populations (i.e., G. f. ferrugineipectus, G. f.

rara, Cauca Valley, and Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta) form a strongly

supported clade that is sister to Andean populations of G. nana (albeit

with low support in the Bayesian species tree), whereas populations from Peru

and Bolivia (i.e., G. f. leymebambae)

are recovered as sister to G. lineifrons

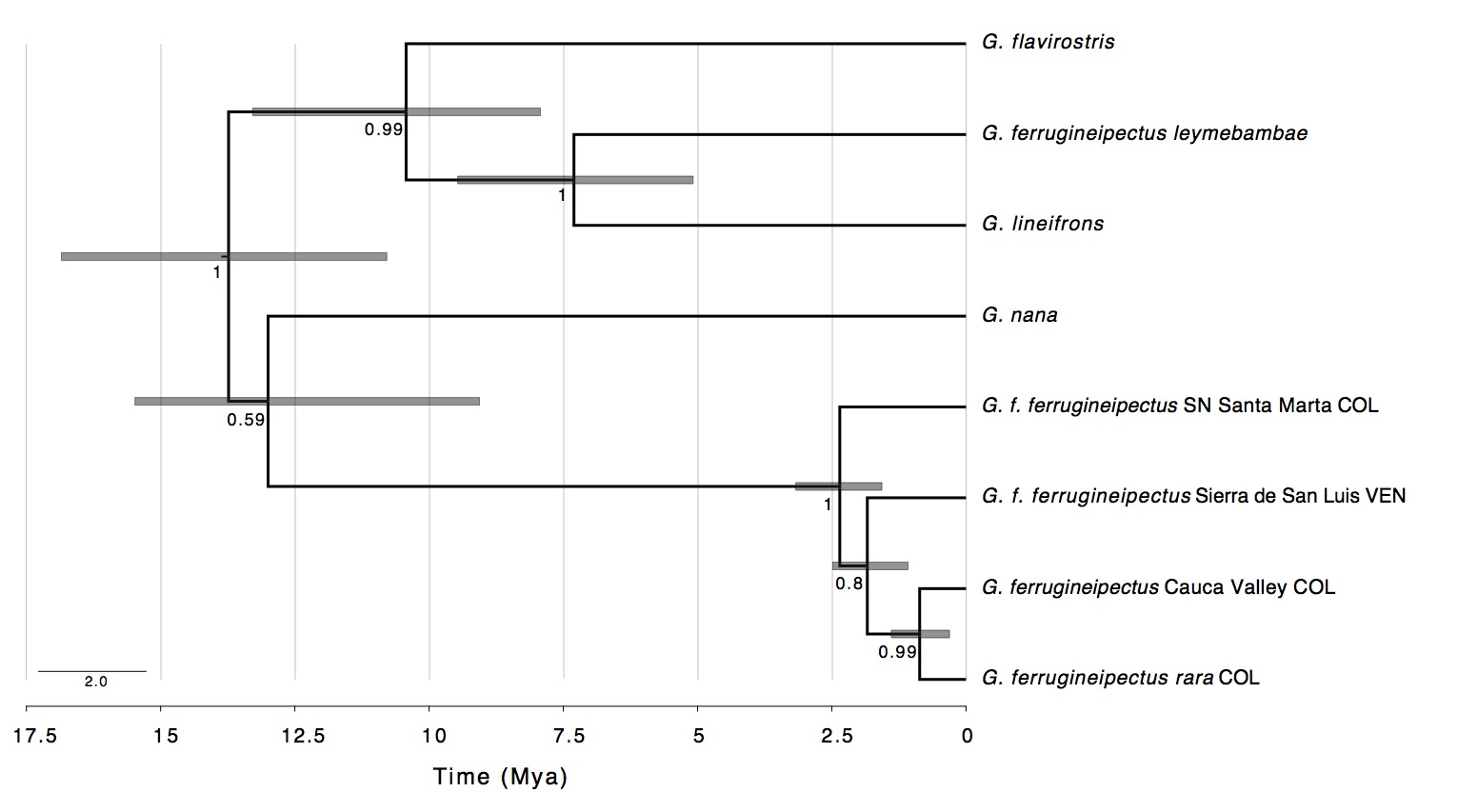

(Fig. 2 and 3). The time-calibrated species tree estimated that the most recent

common ancestor between northern and southern groups split between 10.8 and

16.8 million years ago (mya; Fig. 3). Additionally, northern populations of G. ferrugineipectus exhibit some degree

of geographic structure and differentiation not entirely consistent with current

subspecific boundaries.

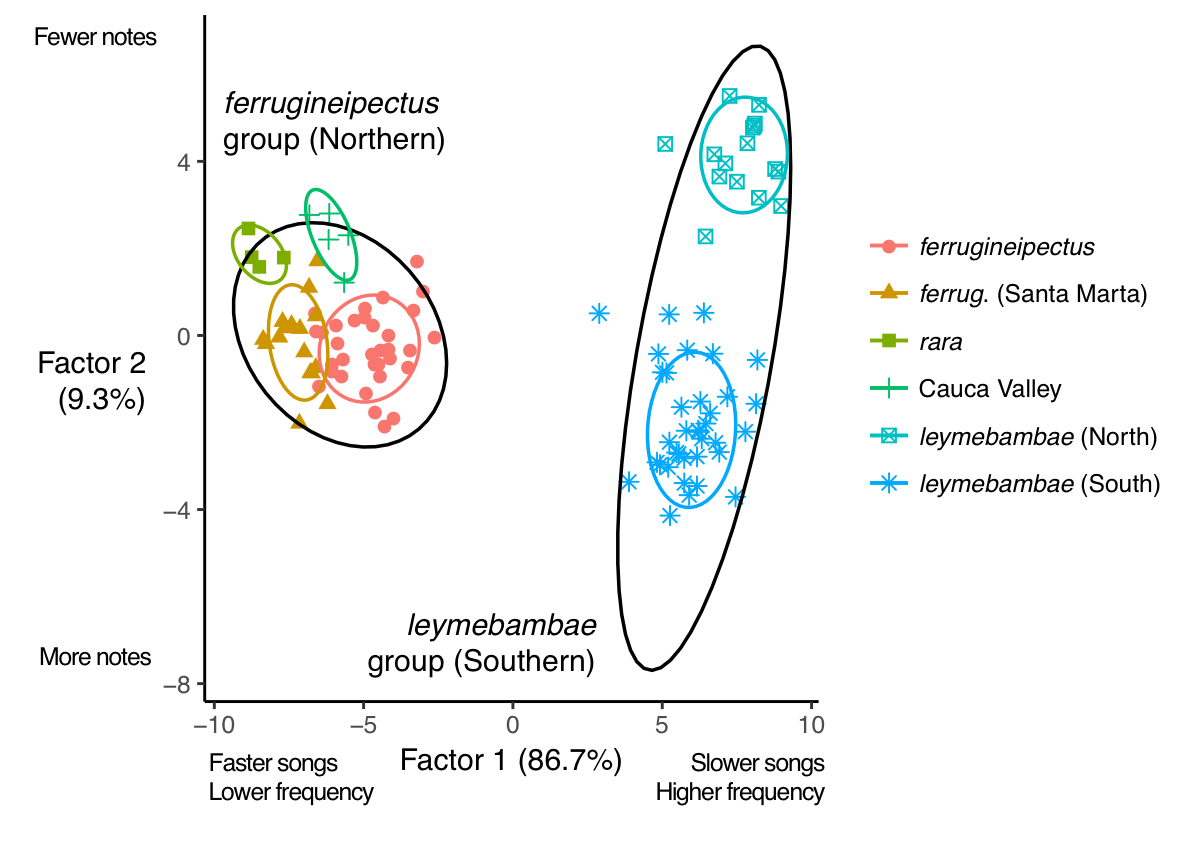

Northern

and southern groups significantly differed in the mean values of 13 of 15 vocal

traits; however, mean note maximum frequency was the only vocal character for

which 95% prediction intervals did not overlap (Figure 5; Table 1). To place

this result into context, we considered the number of vocal characters for

which 95% prediction intervals did not overlap between currently recognized Grallaricula species. The southern group

differed from G. nana in only one

vocal character (song pace), whereas populations in the northern group differed

from G. nana in 3 characters: mean

note maximum frequency, the frequency slope of the song, and the position of

the maximum frequency in the song. Both northern and southern groups differed

from G. lineifrons by several vocal

traits (7 and 4, respectively), and G.

nana differed from G. lineifrons

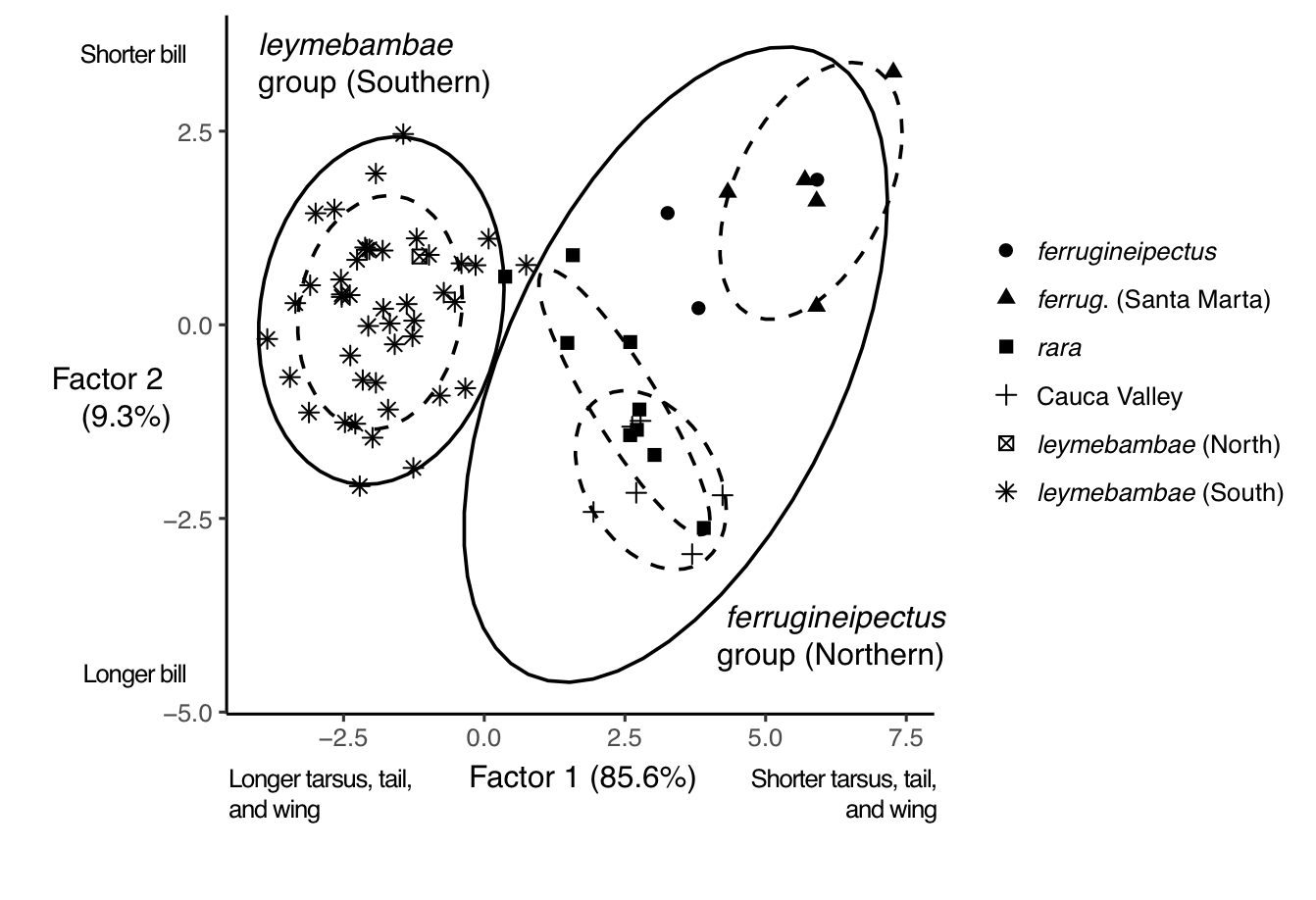

by 8 vocal traits (Table 1). Although northern and southern groups differed

significantly from one another in the mean value of all 6 morphological

characters, none was diagnosable at the 95% prediction level.

Discriminant function analysis

performed well at separating northern and southern groups based on both vocal

and morphological traits (Figure 7). For vocal traits, the cross-validated

correct classification rate was 100% for the northern group and 97.6% for the

southern group. The single discriminant factor loaded most heavily for mean

note maximum frequency. For morphological traits, the cross-validated correct

classification rate was 95.5% for the northern group and 100% for the southern

group; the discriminant factor was primarily composed of tarsus and tail

length.

Proposed Change

We found

that Grallaricula ferrugineipectus,

as currently recognized, is polyphyletic. The southern subspecies G. f. leymebambae is more closely related to G. lineifrons and G.

flavirostris than it is to the northern subspecies G. f. ferrugineipectus and G.

f. rara; in turn, these northern populations are more closely related to G. nana than to G. f. leymebambae. In

fact, the split between the northern and southern clades likely represents the

earliest divergence within the genus Grallaricula

(Fig. 2, GAB unpubl. data), and the age of this split is close to the start of

diversification of the Hylopezus-Myrmothera-Grallaricula

clade, estimated at ~13–21 mya (Ohlson et al. 2013). Hence, G.

ferrugineipectus as currently defined is polyphyletic and comprises

populations that belong to divergent and distinctive clades. We therefore

propose to elevate G. f. leymebambae

to species rank. We recommend the complex be considered to consist of 2 species

and, provisionally, 2 subspecies:

Species Grallaricula

ferrugineipectus (Sclater 1857)

Subspecies Grallaricula f. ferrugineipectus (Sclater 1857)

Subspecies Grallaricula f. rara Hellmayr and Madarász 1914

Species Grallaricula

leymebambae Carriker 1933

References

Angulo

Pratolongo, F., J. N. Flanagan, W.-P. Vellinga, and N. Durand. 2012. Notes on

the birds of Laquipampa Wildlife Refuge, Lambayeque, Peru. Bulletin of the

British Ornithologists' Club 132:162-174.

Athanas,

N., and P. J. Greenfield. 2016. Birds of Western Ecuador: A Photographic Guide.

Princeton University Press, Princeton.

BirdLife

International. 2017. Species factsheet: Grallaricula

leymebambae. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org/.

Carriker,

M. A. 1933. Descriptions of New Birds from Peru, with Notes on Other

Little-Known Species. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of

Philadelphia 85:1-38.

Fjeldså,

J., and N. Krabbe. 1990. Birds of the high Andes: a manual to the birds of the

temperate zone of the Andes and Patagonia, South America. Zoological Museum,

University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Greeney,

H. F. 2013. Rusty-breasted Antpitta (Grallaricula

ferrugineipectus) in T. S.

Schulenberg, editor. Neotropical Birds Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology,

Ithaca.

Hellmayr,

E., and J. Madarász. 1914. Description of a new Formicarian-bird from Columbia.

Annales Musei Nationalis Hungarici 12:88.

Hilty,

S. L., and W. L. Brown. 1986. A guide to the birds of Colombia. Princeton

University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

Krabbe,

N. K., and T. S. Schulenberg. 2003. Rusty-breasted Antpitta (Grallaricula ferrugineipectus) in J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal,

D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, editors. Handbook of the Birds of the World

Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Niklison,

A. M., J. I. Areta, R. A. Ruggera, K. L. Decker, C. Bosque, and T. E. Martin.

2008. Natural history and breeding biology of the Rusty-breasted Antpitta (Grallaricula ferrugineipectus). The

Wilson Journal of Ornithology 120:345-352.

Ohlson,

J. I., M. Irestedt, P. G. Ericson, and J. Fjeldså. 2013. Phylogeny and classification

of the New World suboscines (Aves, Passeriformes). Zootaxa 3613:1-35.

Parker,

T., T. S. Schulenberg, G. R. Graves, and M. J. Braun. 1985. The avifauna of the

Huancabamba region, northern Peru. Pages 169–197 in P. Buckley, M. Foster, E. Morton, R. Ridgely, and F. Buckley,

editors. Ornithological Monographs no. 36: Neotropical Ornithology. American

Ornithologists' Union, Washington, DC.

Ridgely,

R. S., and G. Tudor. 2009. Field guide to the songbirds of South America: the

passerines. University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas.

Schulenberg,

T., and J. Remsen. 1982. Eleven bird species new to Bolivia. Bulletin of the

British Ornithologists' Club 102:52-57.

Schulenberg,

T. S., and T. A. Parker. 1981. Status and distribution of some northwest

Peruvian birds. Condor 83:209-216.

Sclater,

P. L. 1857. Descriptions of Twelve New or Little‐known

Species of the South American Family Formicariidæ. Pages 129-133 in Proceedings of the zoological Society

of London. Wiley Online Library.

Vellinga,

W.-P., J. N. Flanagan, and T. R. Mark. 2004. New and interesting records of

birds from Ayabaca province, Piura, north-west Peru. Bulletin of the British

Ornithologists' Club 124:124-142.

Table

1. Vocal traits that

differ between northern and southern Rusty-breasted Antpittas and 2

congeners following the 95% prediction interval test. Numbers refer to the

following traits: (1) mean note peak frequency bandwidth (Hz); (2) mean note

bandwidth (Hz); (3) mean note maximum frequency (Hz); (4) duration of song (s);

(5) mean duration of each note (s); (6) rate of note delivery (notes per s);

(7) frequency slope of the song (Hz per note); (8) song peak frequency

bandwidth (Hz); (9) song bandwidth (Hz); and (10) position of the highest

frequency note.

|

|

G. ferrugineipectus (North) |

G. nana |

G. lineifrons |

|

G. ferrugineipectus (South) |

3 |

6 |

3, 7, 8, 9 |

|

G. ferrugineipectus (North) |

|

3, 7, 10 |

3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 |

|

G. nana |

|

|

1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10 |

Figure 2. Maximum-likelihood phylogeny of a

subset of the Grallariidae. Note that Grallaricula ferrugineipectus sensu lato (in bold) is

polyphyletic. Black circles at nodes indicate bootstrap support values >70

based on 999 maximum-likelihood replicates.

Figure 3. Bayesian

estimate of phylogenetic relationships and divergence times among a

subset of the Grallariidae. Grallaricula ferrugineipectus sensu lato is polyphyletic;

the northern and southern groups (G. f.

ferrugineipectus and G. f.

leymebambae) last shared a common

ancestor around 13 million years ago (mya). Bars at nodes indicate the 95% highest posterior density for the

inferred divergence time estimates. Numbers at nodes indicate posterior

probability support values.

Figure 5. First 2 factors from discriminant

function analysis separating Rusty-breasted Antpitta subpopulations by

variation in 15 vocal traits. Black ellipses are 95% prediction ellipses for

northern and southern groups; colored ellipses are 75% prediction ellipses for

subspecies.

Figure 7. First 2 factors from discriminant

function analysis separating Rusty-breasted Antpitta subpopulations by

variation in 6 morphological traits. Black ellipses are 95% prediction ellipses

for northern and southern groups; colored ellipses are 75% prediction ellipses

for subpopulations.

Benjamin M. Van Doren, April 2018

__________________________________________________________

Comments from Remsen: “YES. Strongly

supported phylogenetic data make elevation of leymebambae to species rank essentially mandatory.

“We

need to think about English names (not mentioned in the paper). Because leymebambae was incorrectly included in Grallaricula

ferrugineipectus, this isn’t

really a split but an “extraction.” Therefore, I see no need to change the

English name of properly defined Grallaricula ferrugineipectus (Rusty-breasted

Antpitta) – it’s not really a parent-daughter thing in the phylogenetic sense.”

Comments from Robbins: “YES, phylogenetic

data clearly demonstrate that northern and southern ferrugineipectus are not sisters.

Although it is not too surprising that northern birds are more closely

related to nana than leymebambae, I am shocked that southern leymebambae is sister to lineifrons!”

Comments from Stiles: “YES. Clearly two

species are involved. Running through

the various “brown” names in Smithe, here are two

suggestions: Sepia-breasted (if the breast is really that much darker), or

Russet-breasted, which is a shade browner than “Rusty”. Confusingly similar? Perhaps,

but also recognizes the fact that the two are sufficiently similar to have been

considered conspecific ever since leymebambae was described.”

Comments

from Pacheco:

“YES. The evidence gathered clearly supports this proposition.”

Comments from Areta: “YES, a long overdue species treatment now

solidly substantiated with genetic, morphological and vocal data. It is finally

great to see these "enanos cachigordetes"

treated as separate species (as Paul Schwartz aptly called them a long time

ago).”

Comments

from Stotz:

“YES. Lots of data from a variety of

sources. On English names, I don't think I have any clever ideas what to

do. Best I can come up with is Ferruginous-breasted for the northern

group and Leymebamba for the southern group based on

scientific names. Leymebamba is a bad name,

obviously. Maybe Rufous-breasted?”