Proposal

(786) to South American Classification Committee

Split Slaty Thrush Turdus nigriceps into two species

Background: Turdus nigriceps (Slaty Thrush), as recognized by SACC, is a

polytypic species with two disjunct populations. Nominate nigriceps occurs in the Andes, with a curious distribution: it

breeds in southern Bolivia and northwestern Argentina, with another very

disjunct breeding population in southwestern Ecuador and northwestern Peru; and

it is a nonbreeding migrant to the east slope of the Andes from southern

Ecuador south to northwestern Bolivia. The other subspecies, subalaris, breeds in southern Brazil,

northeastern Argentina, and eastern Paraguay, and is a nonbreeding migrant

north to south central Brazil.

The

two taxa have a generally similar plumage pattern, but subalaris overall is paler and browner than nigriceps. Compared to male nigriceps,

male subalaris has upperparts that

are more washed with olivaceous; the crown is concolor with back (crown black

in nigriceps); has a prominent white

crescent on the upper breast, below the throat (crescent lacking in nigriceps); the center of the belly is

more extensively white; and the underwing coverts are white (gray in nigriceps) (Hellmayr 1934, Ridgely and

Tudor 1989). Less attention is paid, at least in the recent literature, to

differences in the female plumage, but female subalaris apparently also has white crescent on the upper breast,

again less apparent in female nigriceps.

See, for example

nigriceps

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/78400441#_ga=2.38393184.237959473.1522697535-1150616374.1458581505

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/29635211#_ga=2.15874421.237959473.1522697535-1150616374.1458581505

subalaris

At

least as late as Hellmayr (1934), nigriceps

and subalaris were recognized as

separate species. They were lumped, without comment, by Ripley (1964), and this

was followed by Meyer de Schauensee (1966). They were split again by Ridgely

and Tudor (1989):

Obviously

well isolated geographically, they also differ in plumage and have rather

different songs, that of Andean [nigriceps]

being more jumbled and musical (not so squeaky).

The

songs of the two are further described as a series of rather high, jumbled

phrases, some of the notes quite high-pitched in nigriceps, compared to a short series of high pitched notes with an

oddly squeaky, bell like quality in subalaris

(Ridgely and Tudor 1989, 2009). I am not aware of any further analysis of these

songs. Representative examples of songs of both can be heard at Macaulay Library and at xeno-canto

(separate pages for nigriceps and for subalaris); examples are

nigriceps

https://www.xeno-canto.org/149111

subalaris

https://www.xeno-canto.org/337440

This

split has been widely adopted (e.g., Clement 2000, del Hoyo and Collar 2016),

but acceptance of the split has not been universal (e.g., Dickinson and

Christidis 2014).

New information: There are several

recent molecular phylogenies of the genus Turdus

that touch on Turdus nigriceps.

Voelker et al. (2007) used only mitochondrial DNA, but had a very wide sampling

of species of Turdus, although

unfortunately they included only nominate nigriceps

(a sample from Argentina). They resolved nigriceps

as a member of a clade that also included Turdus

fulviventris (Chestnut-bellied Thrush), Turdus

olivater (Black-hooded Thrush), Turdus

fuscater (Great Thrush), Turdus

serranus (Glossy-black Thrush), and Turdus

chiguanco (Chiguanco Thrush).

Nylander

et al. (2008) also had wide sampling of species of Turdus, and used both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA. As with

Voelker et al., they included only nominate nigriceps

(a sample from Ecuador), and they too place nigriceps

in a clade with fulviventris, olivater, fuscater, serranus, and chiguanco (although their topology

within this clade is different from that of Voelker et al.).

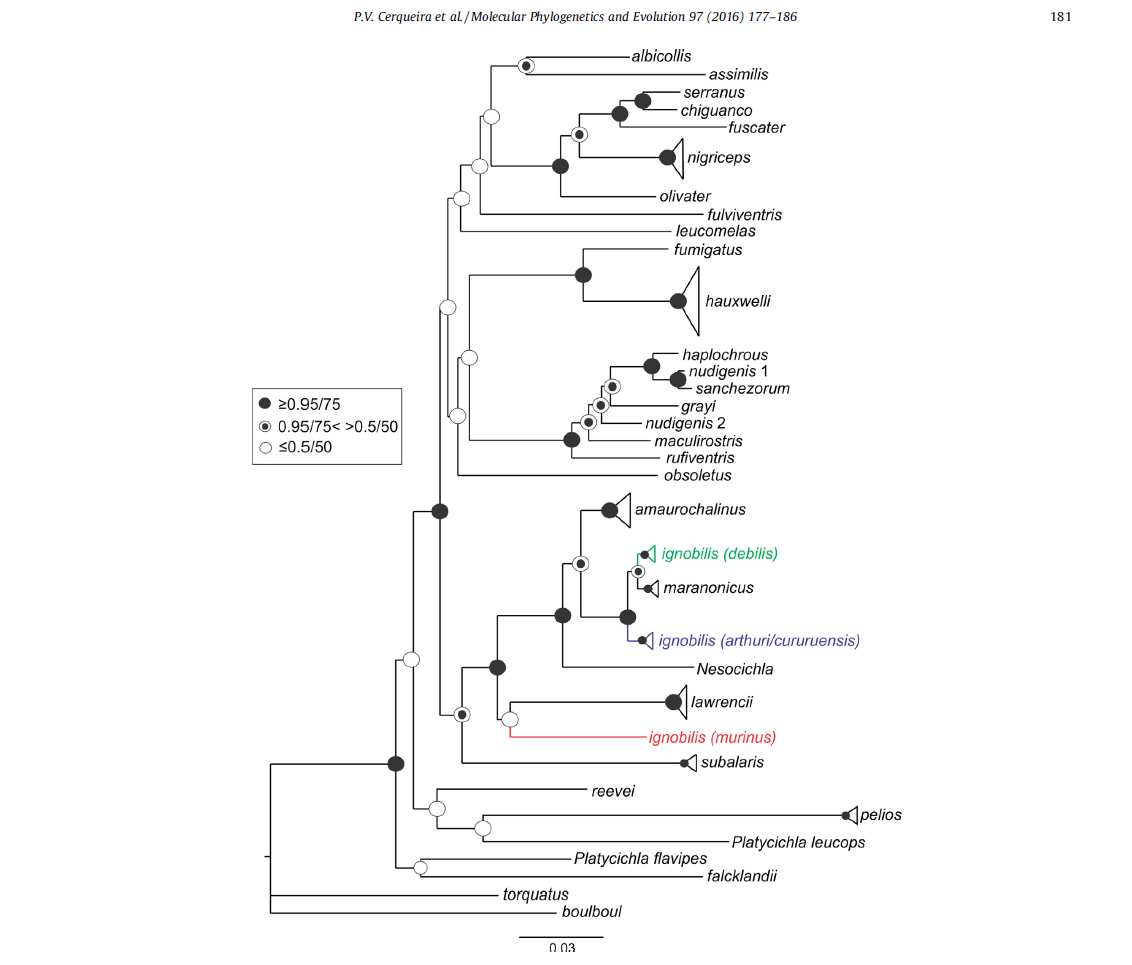

Cerqueira

et al. (2016) used both mtDNA and nuDNA to investigate relationships within the

Turdus ignobilis (Black-billed

Thrush) complex. They sampled extensively within three of the five subspecies

of ignobilis. For data on outgroups,

they primarily relied on mtDNA data from Voelker et al. and from O’Neill et al.

(2011), but Cerqueira et al. also produced fresh data, for both mtDNA and

nuDNA, for nominate nigriceps (two

samples from Bolivia) and for two samples of subalaris (two samples from Brazil). In a by now familiar pattern,

Cerqueira et al. found that nigriceps

belongs to the same clade as fulviventris,

olivater, fuscater, serranus, and chiguanco. In contrast, subalaris belongs to a very different

clade, clustering in a clade with members of the ignobilis group, and with T.

maranonicus (Maranon Thrush), T.

lawrencii (Lawrence’s Thrush), T.

eremita (Tristan Thrush), and T.

amaurochalinus (Creamy-bellied Thrush).

Avendaño

et al. (2017) took another look at the ignobilis

complex, within which they sampled all taxa assigned to ignobilis. The trees that they published did not include as many

species of Turdus as the other

studies, but they included both nigriceps

and subalaris (for both of which they

used data from Cerqueira et al.). Avendaño et al. again recovered subalaris as part of a clade with the ignobilis group, maranonicus, lawrencii, eremita, and amaurochalinus. Nominate nigriceps

is well outside this clade (but its affinities are not resolved here, as the

trees published by Avendaño et al. include only a few species of Turdus outside of the clade that

includes ignobilis).

Analysis: Differences in both

plumage and song are highly suggestive that nigriceps

and subalaris are different species,

as was intuited long ago by Ridgely and Tudor (1989). Those authors assumed,

however, that nigriceps and subalaris still were sister taxa,

whereas the phylogenetic evidence shows that a polytypic Turdus nigriceps is paraphyletic: not only is it clear that nigriceps and subalaris are separate species, but these two are not at all

closely related to each other.

English names: For almost 30 years,

these two species have been known as Andean Slaty Thrush (nigriceps) and Eastern Slaty Thrush (subalaris) (Ridgely and Tudor 1989, Sibley and Monroe 1990,

Clements 1991, Monroe and Sibley 1993, Clement 2000, Clements 2000, Mazar

Barnett and Pearman 2001, Ridgely and Greenfield 2001, Guyra Paraguay 2004,

Gill and Wright 2006, Restall et al. 2006, Clements 2007, Ridgely and Tudor

2009, del Hoyo and Collar 2016). These names of course stem from a time when nigriceps and subalaris were assumed to be sister taxa; knowing that this is not

the case, and if we were starting from scratch, completely different names for

each might be warranted. There is no history of separate names for them,

however. Meyer de Schauensee (1966) (or, I assume, Eugene Eisenmann in Meyer de

Schauensee) proposed the names Black-capped Thrush for nigriceps, and Slaty-capped Thrush for subalaris, but those are not terrific names, and I am not aware

that these ever were adopted by anyone. It is best, then, to retain the names

that are in (very) wide use. Note that Slaty Thrush is not hyphenated in this

case, as it is not a group name.

Recommendations: I suggest breaking this

proposal down into two parts:

Part

A): to split Slaty Thrush Turdus

nigriceps into two species. My recommendation is Yes.

Part

B): to adopt Andean Slaty Thrush as the English name for Turdus nigriceps, and Eastern Slaty Thrush as the English name for Turdus subalaris. My recommendation is

Yes.

Literature

Cited:

Avendaño,

J.E., E. Arbelaez-Cortés, and C.D. Cadena. 2017. On the importance of

geographic and taxonomic sampling in phylogeography: a reevaluation of

diversification and species limits in a Neotropical thrush (Aves, Turdidae). Molecular Phylogenetics and

Evolution 111: 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2017.03.020

Cerqueira,

P.V., M.P.D. Santos, and A. Aleixo. 2016. Phylogeography, inter-specific limits

and diversification of Turdus ignobilis

(Aves: Turdidae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 97: 177–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2016.01.005

Clement.

P. 2000. Thrushes. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

Clements,

J.F. 1991. Birds of the word: a checklist. Fourth edition. Ibis Publishing

Company, Vista, California.

Clements,

J.F. 2000. Birds of the word: a checklist. Fifth edition. Ibis Publishing

Company, Vista, California.

Clements,

J.F. 2007. The Clements Checklist of the birds of the world. Sixth edition.

Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York.

Dickinson,

E.C., and L. Christidis. 2014. The Howard & Moore complete checklist of the

birds of the world. Fourth edition. Volume 2. Aves Press, Eastbourne, United

Kingdom.

Gill,

F., and M. Wright. 2006. Birds of the world: recommended English names.

Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

Guyra Paraguay. 2004.

Lista comentada de las aves de Paraguay/Annotated checklist of the birds of

Paraguay. Asociación Guyra Paraguay, Asunción.

Hellmayr,

C. E. 1934. Catalogue of birds of

the Americas. Part VII. Field Museum of Natural History

Zoological Series volume 13, part 7.

Mazar Barnett, J., and

M. Pearman. 2001. Lista comentada de las aves Argentinas/Annotated checklist of

the birds of Argentina. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Meyer

de Schauensee, R. 1966. The species of birds of South America and their distribution.

Livingston Publishing Company, Narberth, Pennsylvania.

Monroe, B.L., Jr., and

C.G. Sibley. 1993. A world checklist of birds. Yale University Press, New

Haven, Connecticut.

Nylander, J.A.A., U.

Olsson, P. Alström, and I. Sanmartin. 2008. Accounting for phylogenetic

uncertainty in biogeography: a Bayesian approach to dispersal-vicariance

analysis of the thrushes (Aves: Turdus).

Systematic Biology 57: 257-268. https://doi.org/10.1080/10635150802044003

O’Neill,

J.P., D.F. Lane, and L.N. Naka. 2011. A cryptic new species of thrush

(Turdidae: Turdus) from western

Amazonia. Condor 113: 869-880. https://doi.org/10.1525/cond.2011.100244

Restall,

R., C. Rodner, and M. Lentino. 2006. Birds of northern South America: an

identification guide. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut.

Ridgely,

R. S., and P. J. Greenfield. 2001. The birds of Ecuador. Cornell University

Press, Ithaca, New York.

Ridgely,

R. S., and G. Tudor. 1989. The birds of South America. Volume I. University of

Texas Press, Austin, Texas.

Ridgely,

R. S., and G. Tudor. 2009. Field guide to the songbirds of South America. The

passerines. University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas.

Ripley,

S.D. 1964. Subfamily Turdinae,

thrushes.

Pages 13-227 in E. Mayr and R.A. Paynter, Jr. (editors), Check-list of birds of the world. Volume

X.

Museum of Comparative Zoology, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Sibley, C.G., and B.L.

Monroe, Jr. 1990. Distribution and taxonomy of birds of the world. Yale

University Press, New Haven, Connecticut.

Voelker,

G., S. Rohwer, R.C.K. Bowie, and D.C. Outlaw. 2007. Molecular systematics of a

speciose, cosmopolitan songbird genus: defining the limits of, and

relationships among, the Turdus

thrushes. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 42: 422-434.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2006.07.016

Tom

Schulenberg, April 2018

__________________________________________________________

Comments

from Robbins:

“A. YES, genetic data clearly establish that nominate nigriceps and subalaris

are not closely related and subalaris

merits recognition as a species.”

Comments

from Remsen:

“A. YES. Genetic data require recognition of subalaris as a species.

Amazing result given phenotypic similarity.

“B.

NO. This isn’t a split involving sister

taxa; if that were the case, I would vote yes for the proposed names. But the key finding is that these two aren’t

particularly closely related. Thus

retaining “Slaty Thrush” in their names perpetuates that misconception, even

unhyphenated. Yes, they are both slaty

in terms of color, but so are other thrushes.

Why maintain the connection in the English name? The adoption of Eastern Slaty Thrush by HBW

etc. was done under the assumption that the two species were sisters, and so we

can only speculate on whether that name would have been adopted had the true

relationships been known. The “Eastern”

part makes sense only as counterpart to Andean Slaty Thrush. Thus, I don’t think we should worry about

stability given that the existing name is based on misinformation. Leaving nigriceps

as Slaty Thrush has the advantages of (1) that name staying with the species

for which it was intended and (2) avoiding a compound name that in this case

does not reflect relationships. That’s

the easy part. The hard part is

concocting a novel name for subalaris.” Hellmayr (1934), who treated it as a separate

species, called it “Behn’s Thrush”, for W. F. G. Behn, who according to Beolens

et al. (2014; The Eponym Dictionary of Birds) was “a German explorer who is

famed for his crossing of South America.

He was the Director of the Zoological Museum of Christian Albrechts

University of Kiel (1836-1868). This is the same Behn of Myrmotherula behni, Trogon curucui behni, and Brotogeris chiriri behni.

Most people don’t like eponymous English bird names, so this would not

likely be a popular choice. “Subalaris”

means “under the arms”, so no help there.

However, if we put our heads together, I predict we’ll be able to do

better than “Eastern Slaty Thrush”, which in my opinion is not only insipid but

misleading.”

Comments

from Stiles:

“A: YES to splitting subalaris from nigriceps, a move clearly mandated by

the phylogeny; B. YES to retaining Black-capped for nigriceps; C: NO, for reasons given by Van. A couple of suggestions (I haven’t checked

the voluminous English nomenclature of Turdus

for synonyms: Plain-capped (to contrast with Black-capped); or Olive-gray, to

emphasize the color difference of the dorsum.”

Comments

from Jaramillo:

“A: YES – straight forward. B YES – they are in usage already, so in terms of

name stability and the fact there are no good alternative names that are in

use, I think one has to go with this choice.”

Comments

from Stotz:

“A: YES. B. NO. I don’t have a vote here at this

point. I agree that the fact that the

two Slaty Thrushes are not closely related undermines Andean and Eastern Slaty

Thrush as a reasonable alternative. I

also have a problem with leaving nigriceps

as Slaty Thrush. 1st it

doesn’t follow our “rule” regarding English names, which ideally we would

follow. But the real problem is that I

think most people think of “Slaty Thrush” as being the widespread eastern

migratory form. I think applying it to

the much more poorly known Andean form is a mistake. One final comment on this is it seems like a

number of committee members prefer keeping the old English name with the nominate

form when I split occurs. I can be

talked into that, but in general, I think it is a mistake, because you end up

with a daughter taxon with both the same English and scientific name as the

broader species concept. This makes

confusion over what species concept you are using more of an issue than when

the old English name and <in prep>

Comments

from Pacheco:

“YES. Highlighting one of the affirmatives of Tom's proposal (…) “it clear that

nigriceps and subalaris are separate species, but these two are not at all

closely related to each other.”

Comments from Areta: “YES. Phylogenetic data clearly supports the recognition

of two species, as vocalizations and plumage have long suggested. It is

interesting that these two are not even sister species.”

Comments

from Zimmer:

“A. YES. This

one was overdue, based on plumage differences, vocal differences, ecological

differences, and the fact that the lump was a typical Peters-style fiat without

comment. All of this now supported by

genetic data. B. NO, for the reasons cited by others. “Slaty Thrush” no longer works as a group

name, given that the two species are not sisters.”

Proposal

(786B.1) to South American Classification Committee

Establish

English names for Turdus nigriceps and

Turdus subalaris

Proposal

786B above (Eastern Slaty Thrush and Western Slaty Thrush) did not pass, and

because I was one of the NO voters, I’ll take responsibility for another

iteration. See comments above for

background.

The

objection to Eastern Slaty Thrush and Andean Slaty Thrush, despite their long

history documented by Tom, is that even without hyphens, these names perpetuate

the incorrect notion that the two species are related. These names would in a sense negate finding

of Cerqueira

et al. (2016) and Avendaño et al. (2017) that these two are not even in the

same section of the genus --- see the tree in the main proposal. Turdus

nigriceps is sister to a group of largely Andean thrushes that are slaty blackish

to black (T. fuscater, T. serranus, T. chiguanco), whereas subalaris is sister to a group of

lowland thrushes that are more brownish (T.

ignobilis etc.). (Check online

photos and the specimen photos below of Turdus

nigriceps to see how much darker it is than T. subalaris; thus, fits

fairly nicely in the blacker Andean group.)

Reversing my initial comments (above), retaining

Slaty Thrush for one of the daughters IS unacceptable in this case in my

opinion – it’s a good example of why the guideline of creating new names for

daughters is the best practice because who would remember which is which? Doug thinks of subalaris when he sees Slaty Thrush, but I’m the opposite – for me,

and probably others working with Andean birds, “Slaty Thrush” has always been nigriceps. Furthermore, “Slaty” is not a very good name

for subalaris: see the photos – it’s

really not much grayer than a lot of Turdus,

in contrast to the obviously slaty nigriceps. In fact, I now wonder why they were

considered conspecific in the first place; Hellmayr certainly had it right, but

Ripley (Peters) botched this badly.

As you all know, I’m a major proponent

of stability in English names because “improving” them defeats their

purpose. The exception, in my view, is

when they are misleading. At face value,

Andean Slaty and Eastern Slaty aren’t descriptively misleading; however, they

were clearly intended to connote a sister relationship, even before the Cerqueira

et al. (2016) and Avendaño et al. (2017) data falsified this. Thus, to perpetuate those names is actively

misleading. Stability in this case, in

my opinion, needs to be disrupted.

In this case, stability = liability in my opinion.

So, I recommend going with the Meyer de

Schauensee names mentioned by Tom, even though they were never used by anyone

else: Black-capped Thrush for nigriceps,

and Slaty-capped Thrush for subalaris. They are not diagnostic, but at least not inaccurate. Black-capped is a translation of the

scientific name, aiding remembering which one is which, and Slaty-capped

maintains a slim connection to Slaty. A

potential objection to both of them being “Something-capped” might still imply

a relationship, being the only South American “-capped” thrushes, so if someone

has a better idea for subalaris, I’m

receptive. I assume Hellmayr’s “Behn’s

Thrush” (see comments above) is not a popular choice.

Van Remsen, June 2018

Comments

from Stotz:

“YES. I think this is the best option we

have. At least they are not completely

new names, and don’t give the misimpression of a close relationship between the

two species.”

Comments from Josh Beck:

“Narosky & Yzurieta's "Birds of Argentina

and Uruguay" guide is the only reference I know that doesn't use Andean

and Eastern Slaty Thrush but rather uses Black-capped Thrush for nigriceps and Slaty Thrush for subalaris. I don't have any strong

opinions on the names proposed, but if there is a strong dislike for

Slaty-capped Thrush an alternative that occurs might be Mata Thrush or Atlantic

Thrush or another more clever biogeographic reference, as this is the only Turdus that is essentially endemic to

the Atlantic Rainforest.”

Comments from Jaramillo: “YES

-- go with the “-capped” names, I don’t think they suggest relationship in this

case.”

Comments from Schulenberg: “NO. Neither name is inaccurate, but at the same time neither gets

to the heart of what each species looks like. And both names are pretty blah;

one blah name I could handle, two similar blah names is not appealing. And I

might have trouble remembering which blah name refers to which species. Dan

Lane says that in his experience, nigriceps

typically is in alder thickets, and so he suggested to me that Alder Thrush

would be an appropriate name for that species. I could live with Alder Thrush (nigriceps) and Slaty-capped Thrush, if

anyone else would go along. I'm not worried about coining novel names in this

case; as far as I am aware, no one ever has used the names (coined by

Eisenmann?) in Meyer de Schauensee, so these effectively are new names anyway.

Even better, of course would be a novel name for subalaris that, like Alder, reflects its biology.”

Comments from Stiles: “Black-capped is fine with me, and I'll go with Slaty-capped if

that gets a majority, but I really don't like this name much - mainly because

the bird is not really "capped" at all - its upperparts appear

uniform slaty gray. Is there a Slaty-backed Thrush anywhere else?”

Comments from Zimmer: “NO to “Black-capped” and “Slaty-capped” as English names for nigriceps

and subalaris. I don't either of

these names is particularly descriptive (neither

nigriceps nor subalaris looks

particularly "capped"), and by going with something-capped for both

species, I think that implies sister-status in the same way that

"something Slaty Thrush" (with or without the hyphen) does.

“I could go with “Alder Thrush” for nigriceps, or something

like “Cinereous Thrush” or “Saturnine Thrush”, since it is distinctly darker

and grayer than subalaris. For subalaris,

I would propose a novel name based on what I think is its most distinctive

character — its voice. This bird has a unique, jangling quality to the

song that is not matched by any bird that I can think of (and very different

from the vocal quality of nigriceps). A quick look at an online dictionary shows the

verb form of “jangle” defined as: make

or cause to make a ringing metallic sound, typically a discordant one “a bell

jangled loudly”. The noun form is

described as a “ringing metallic sound”. These definitions fit the jangling, discordant,

bell-like songs of subalaris perfectly. So, I would propose calling it “Jangle

Thrush”, "Jangling Thrush", or, the slightly less descriptive

“Chiming Thrush”, as a name that is both novel, memorable, and descriptive.”

Comments from Mark Pearman: “I agree that these species do not look at all capped

in the field and would avoid those names, It's the whole of the head that

contrasts in nigriceps yet this can

be difficult to see when you are often looking up at them high in the

canopy.

“Yes,

nigriceps occurs in alder woodlands,

but it is far more common and even abundant in the mixed yungas forest below

that i.e. c. 600 to 1500 m. So, while not being exclusive to alder woodland, in

some areas, Glossy-black Thrush T.

serranus is more common than nigriceps

in that habitat, and again I would avoid the name Alder Thrush.

“It

is true that these thrushes have very distinctive songs. To my ear nigriceps delivers a jangling series,

whereas subalaris sounds more like

chiming. This is subjective and different people are likely to have a different

interpretation.

“Finally,

and although the species are not closely related, I have no problem at all with

the names Andean Slaty Thrush and Eastern Slaty Thrush. Firstly they have been

around for many years and are in common usage. Secondly, they are informative

and tell you where the birds are found and that (the males) are slaty.”

“I

recommend sticking with Andean Slaty Thrush T.

nigriceps and Eastern Slaty Thrush T.

subalaris.”

Comments

from Dan Lane:

“For subalaris, some

possibilities could be Mata Atlantica Thrush, Clanging Thrush, Chiming Thrush.”

Additional comments from Stiles: “The Slaty Thrush split

was accepted 11-0, no problem. However, the E-names are sufficiently bogged

down that no clear consensus seems to be emerging. So, a couple of fresh

suggestions that hopefully won't simply muddy the waters further. Going through

the extensive index or E-names for "thrush" in HBW vol. 10, I found

(to my surprise) that there is no "Black-headed" Thrush! So, given

the objections to the "capped" names and a fairly general dislike for

E. and W. Slaty Thrushes, I would suggest Black-headed Thrush for nigriceps - it is a more direct

translation of the Latin name, and also more accurately descriptive. For subalaris, several people have suggested

something recalling its voice, but the suggestions have been a bit

contradictory: "jangling" has been proposed for subalaris, but Mark P. applies it to nigriceps! R&T's description of the song of subalaris is "squeaky, bell-like"

but I have a hard time uniting "squeaky" with "jangling",

and "chiming" to me implies a more ringing, pure tone. However,

another name given in HBW for subalaris

is "Blacksmith" Thrush. I suspect that this may derive from a common

name given by Pinto as used in Brazil: "ferreiro". Also somewhat in

line here: a synonym of subalaris

given by Hellmayr was "metallophonus". All this brought out of deep

recall an experience of mine around 1971 in a tiny hamlet in Costa Rica, when I

spent a night in a room near to a blacksmith's forge.. he was working late, and

I remember dozing off to the accompaniment of his hammer going

"clink..clink..clink". So, how about "Clinking Thrush"??

(Try this on with those familiar with this species..)”

Final

comments from Remsen:

“This proposal is officially stalemated.

Even expanding the vote to include Mark Pearman and Steve Hilty will not

help because it is clear that Mark, from his comments above, would vote

NO. So, I am asking one or more of the

NO voters (Tom, Doug, Kevin; or Mark P.) to try a new proposal. Note that because this split does not involve

true phylogenetic parent-daughter split, one of the pseudo-daughters,

presumably nigriceps, could retain “Slaty Thrush”.

Comments

from Stiles:

“Regarding E-names, I suggested Black-headed Thrush for nigriceps (but could live with Slaty Thrush if this looks like

achieving a majority –after all, it is the “slatier” of the two). If the people

who prefer a voice-related name for subalaris

can get together on this, I’ll go along. Not much to recommend regarding

conspicuous field marks in its almost spectacularly blah plumage.. However,

looking through my Smithe color swatches, the closest I come is –Drab! So I’ll

toss Drab Thrush or Drab-gray Thrush into the hat for selection of an E-name!”

________________________________________________________

Note from Remsen: With a 3-3 vote on 786B.1, we move on to this

one:

Proposal

(786B.2) to South American Classification Committee

Establish

English names for (i) Turdus nigriceps

and (ii) Turdus subalaris

(i) Turdus nigriceps. This is the first of

two subproposals to try to establish common names for members of the Slaty

Thrush complex. This proposal would deal with Turdus nigriceps.

Without

rehashing everything from the prior 2 proposals dealing with this subject, I

will just give a brief synopsis.

Slaty

Thrush Turdus nigriceps was formerly considered one species with two

subspecies. Proposal 786 passed to split into 2 species, and among the various

evidence presented to split the species Avendaño et al. (2017) showed they are

not each other closest relatives.

Andean

Slaty Thrush is the previous name used for when nigriceps was considered

its own species. Although not the only thrush species in the Andes, I believe a

simple solution would be to just shorten the name already in use to Andean

Thrush.

Recommendation: To adopt Andean

Thrush as the common name for Turdus nigriceps.

A

YES vote on subproposal i is in support of Andean Thrush, and a NO is for

something besides Andean Thrush.

(ii) Turdus subalaris

Slaty

Thrush Turdus nigriceps was formerly considered 1 species with 2

subspecies. Proposal 786 passed to split into 2 species and among the various

evidence presented to split the species Avendaño et al. (2017) showed they are

not each other closest relatives. With the birds not being closely related

keeping Slaty as part of either name is not a good option because it implies a

relationship between the two that has been refuted.

Eastern

Slaty Thrush is the previous name used for when subalaris was considered

its own species. As this is no longer considered a viable option, a new name

for subalaris is needed. Based on comments from Proposal 786B.1, I am

suggesting Atlantic Forest Thrush. Alternatively in looking at Birds of South

America Volume 1 in the description of subalaris Ridgely & Tudor

(1989) mentioned a white crescent on the upper chest being present in both

sexes and actually more noticeable in the female that is lacking in nigriceps.

Perhaps Crescent-chested Thrush would be a more favorable option.

Recommendation: While I think either

name would be accurate, I think Crescent-chested Thrush would be a better

choice.

So

let’s break the subproposal ii down as follows:

A YES would be in favor of Atlantic Forest Thrush, and a NO would be for

Crescent-chested Thrush or something else again.

Literature

cited:

Avendaño, J.E., E. Arbelaez-Cortés, and C.D. Cadena. 2017. On the

importance of geographic and taxonomic sampling in phylogeography: a

reevaluation of diversification and species limits in a Neotropical thrush

(Aves, Turdidae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 111: 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2017.03.020

Ridgely, R. S., and G. Tudor. 1989. The birds of South America. Volume

I. University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas

Dan Zimberlin,

February, 2020

Comments

from Remsen:

(i) NO. “Andean Thrush” is just too

misleading for a species that does not occur throughout the Andes. (ii). NO. I

think this is the second-best name, but I’m holding out for Blacksmith Thrush.

Comments

from Schulenberg:

(i) NO. The names currently on the table for Turdus

nigriceps are "Andean Thrush" or "something besides Andean

Thrush". Andean Thrush does not work for me; the species is Andean, but

its distribution within the Andes actually is rather limited. So I vote NO on

7862. but in the vein of something besides Andean Thrush, I continue to endorse

Andean Slaty Thrush.”

Note from Remsen: With a 0-4/5 vote on 786B.2, we move on to

this one:

Proposal

(786B.3) to South American Classification Committee

Establish

English names for (i) Turdus nigriceps

and (ii) Turdus subalaris

Although, like Tom Schulenberg

and Mark Pearman, I’d strongly prefer

the rather widely used Andean Slaty Thrush T. nigriceps and Eastern

Slaty Thrush T. subalaris, for the English names of the two species

split from T. nigriceps, I understand how some on the committee might be

concerned that those names imply a sister-species relationship. I realize that

horse may have permanently left the barn.

If so, perhaps this alternative might be considered as a way to

break the English name log-jam:

I’d propose using Andean Slaty Thrush for T. nigriceps and

Blacksmith Thrush for T. subalaris.

i. The advantages of using Andean

Slaty Thrush for T. nigriceps are several:

- It continues to

retain and associate the “slaty” component of the English name with T.

nigriceps, which is a long-established connection.

- It associates its

geographic range with this species, yet it is a more precise name than

“Andean” Thrush which could apply to any number of Turdus species

found throughout the Andes.

- It doesn’t have to

imply that that there must be another “Slaty” Thrush any more than, for

example, Crowned Slaty Flycatcher implies that there is another “Slaty”

flycatcher.

ii. The advantages of using Blacksmith Thrush for T. subalaris

include:

- Removing “slaty”

from the name eliminates any concern about suggesting a sister

relationship with T. nigriceps.

- “Blacksmith

Thrush” essentially already exists as a common name for this species since

it is a direct translation of the Portuguese name for this Brazilian

near-endemic: sabiá-ferreiro.

- Blacksmith Thrush

associates the voice of the species with its English name and, as a

translation of the Portuguese, obliquely reinforces its geographic range

with the species.

David Donsker, May 2020

Comments from Jaramillo: YES - Andean Slaty for nigriceps,

and Blacksmith for subalaris. Sounds

good to me. I particularly like Blacksmith Thrush as a name, and Andean Slaty

retaining the slaty part is good too. I do not think this causes any problems,

at least to my eye.”

Comments from Zimmer: “YES” to making “Andean Slaty

Thrush” the English name for T. nigriceps, and “Blacksmith Thrush” the

English name for T. subalaris. I

really think this is the best path forward, for all of the reason cited by

David Donsker in the Proposal. I had

proposed “Jangling Thrush” for subalaris as a way to highlight its

unique voice, and, although I still think that “Jangling” more accurately

describes the quality of the voice of subalaris, “Blacksmith” at least

references that unique voice, and is an English translation of the common name

in Brazilian Portuguese. Using “Andean Slaty Thrush” for T. nigriceps

retains the name that it has gone by (at least informally) for 30 years, while

avoiding the implied sister status to T. subalaris that was previously a

sticking point. Win, Win.”

Comments from Stiles: “My preference for nigriceps

is Black-headed Thrush, for the reasons stated.. but if this doesn't get

off the ground, I would be willing to accept Andean Slaty Thrush, if one vote

were to reach quorum. Blacksmith Thrush is fine by me for subalaris.”

Comments from Remsen: “(i) YES, largely in the

interests of compromise and moving forward; CLO’s “Birds of the World” project

already uses this. (ii) YES, good name, far better than the insipid and

misleading “Eastern Slaty Thrush”, which unfortunately perpetually associates it

with a species to which it is not closely related.”