Proposal (818) to South American

Classification Committee

Split Pyrocephalus rubinus into multiple species

Background:

The

Vermilion Flycatcher is a widespread, common species that forms a monotypic

genus. It is not a species that has stood out taxonomically, other than it

often gets called out as unusual for a tyrannid because the male is so brightly

and distinctively colored. What has also caught the attention of some is that

while male plumage of various geographical forms is similar, the plumages of

females are not, with some being quite distinctive … specifically, those from

the Galapagos islands.

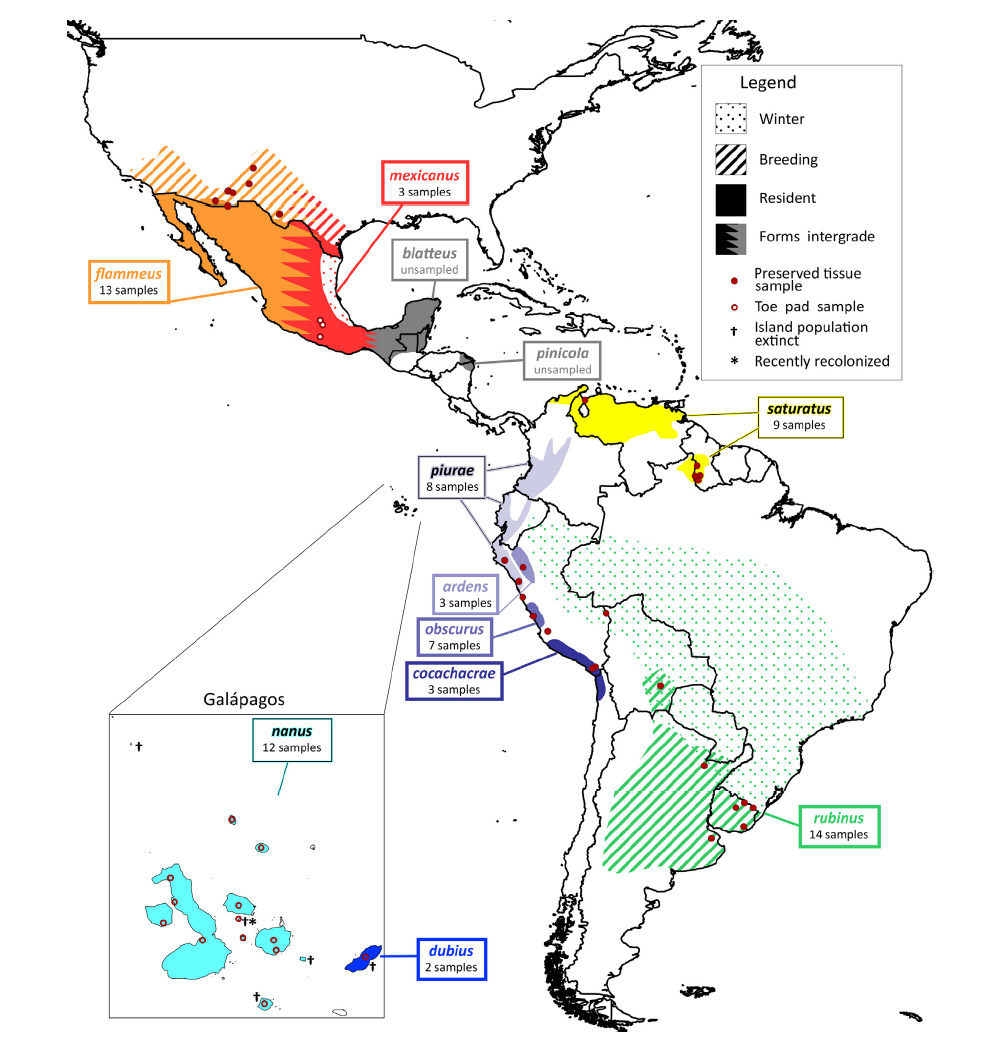

Pyrocephalus rubinus

is very widespread and it shows substantial geographic variation with 12

traditionally recognized subspecies (see distribution map below), much of it

based on differences in female plumage. Although no suggestions to separate the

species into multiples has been made in the past, it is worthwhile to note that

a largely ignored paper by DeBenedictis (1966) notes the radically different

voice of one of the Galapagos populations. DeBenedictis described the aerial

display and vocalization of one population (Isabela Island) in the Galapagos

and confirmed that it is fundamentally distinct from mainland populations.

Rather than a rising series of notes as on the mainland, the Galapagos

population gives a single repeated note. Based on this paper, one would think that

the single species status of Pyrocephalus rubinus would have been called into

question, but as mentioned above this note has largely been ignored, although

recent authors have suggested that P. rubinus is more than one

species (Ellison et al., 2009; Farnsworth and Lebbin, 2004.). Recordings of the

Galapagos birds have not been widely available. In his first trip to Galapagos,

A. Jaramillo was able to obtain poor recordings of the Isabela population of

the Vermilion Flycatcher and confirmed the description of the vocal display as

noted by DeBenedictis (1966).

New Information:

Carmi et

al. (2016) took a fresh look at Pyrocephalus, with molecular datasets in order to

clarify the relationships of taxa within the genus. A total of 85 individuals

was sampled, from 10 of the 12 named subspecies in Dickinson and Christidis

(2014). Two mitochondrial protein-coding genes (ND2 and Cyt b)

were extracted as well as two nuclear loci (ODC and FGB5).

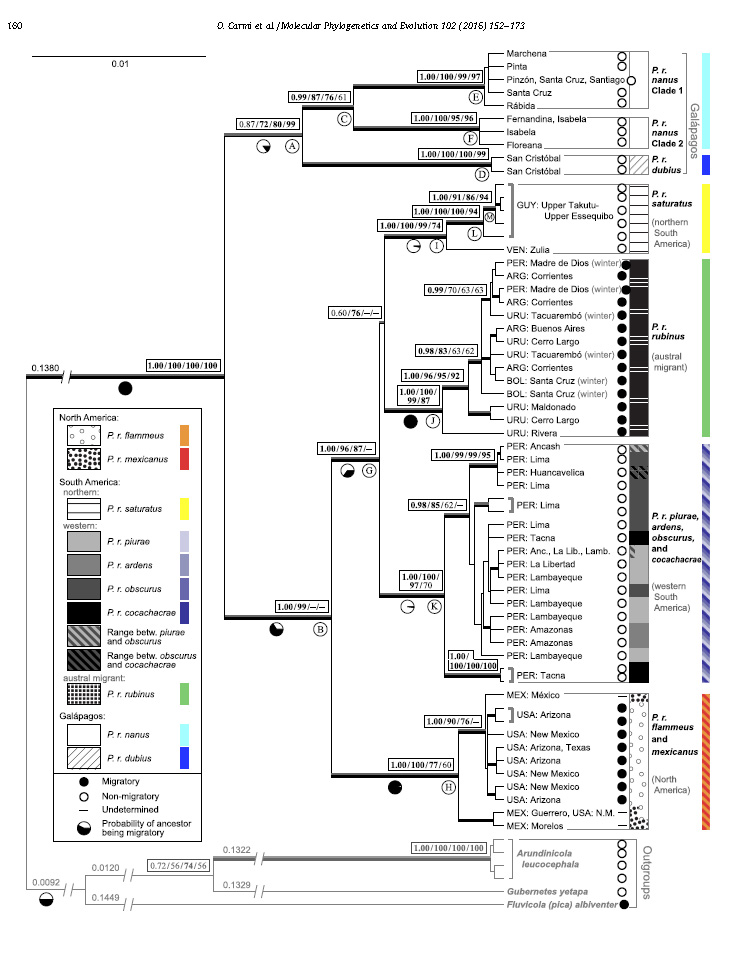

The mitochondrial DNA tree shows that Pyrocephalus

is monophyletic and is separated by a very deep branch from closest

relatives. Seven clades show up in the

data, including three from the Galapagos Islands. These clades from two sister

groups, one of the three clades from the Galapagos, and the other of the

remaining four clades from the continent. In the Galapagos, one clade

corresponds to the subspecies dubius from San Cristobal Island, the geologically

oldest island in the archipelago with a member of Pyrocephalus. The other two

correspond to nanus,

one clade from the older northern islands (Pinta, Marchena, Santiago, Rábida,

Pinzón, and Santa Cruz) and the other from the younger southern and western

islands (Fernandina, Isabela, and Floreana). The continental clades separate

into two groups: a South American group and a North American group. The South

American clade further separates into the austral migratory rubinus

group, the populations along Western South America, and those in northern South

America.

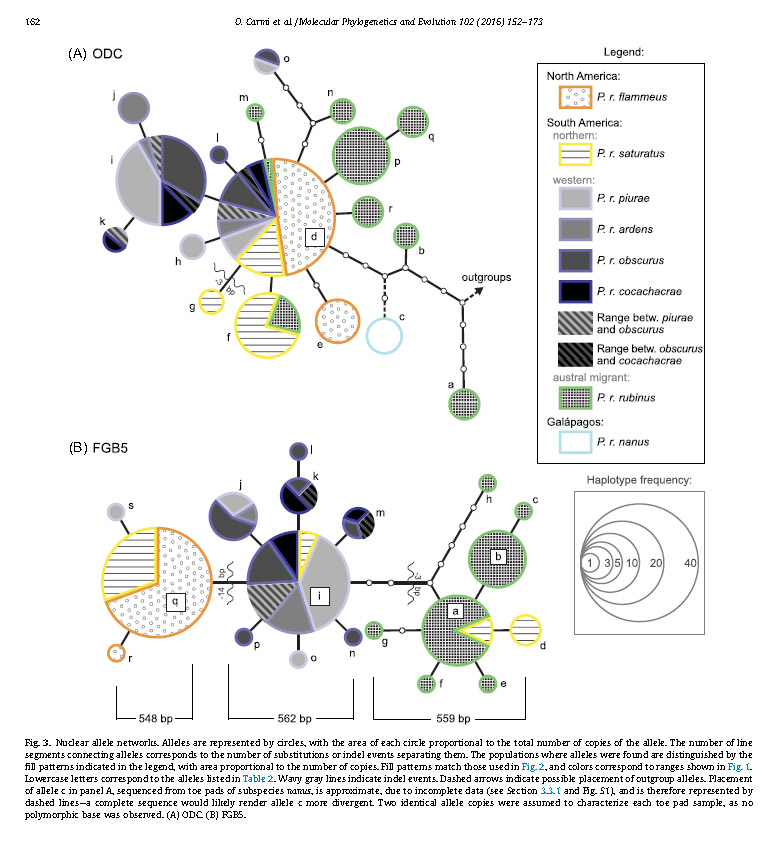

The nuclear allele

networks show a different pattern. In the ODC network, one allele (d) was found

throughout continental populations. Of the five alleles that differed from

allele d by more than one substitution, three were found in Austral rubinus.

The possible root of the allele network was closer to two of these rubinus

alleles. A total of seven alleles were unique to rubinus. One allele was

unique to nanus

from the Galapagos. The highest allele diversity was found in rubinus.

In the FGB5 network there were three groups of alleles, one of several alleles

found in the North American clade, one of birds from the Western South American

clade, and one of rubinus

the Austral migratory clade. Structure

was evident in this dataset; alleles from rubinus were all

characterized by a 3-bp deletion, North American birds by a 14-bp deletion.

Again, rubinus

showed the highest allele diversity of any group. No nanus data was available for this gene.

Galapagos

– the separation between the Galapagos group and the mainland group is

estimated to be roughly a million years ago. These birds are smaller than

mainland birds, with visibly different female coloration. Males are different

as well, with a more restricted red cap than mainland birds. Structurally the

Galapagos birds have very short, weak tails, and short, rounded wings. As noted

above, nanus

is vocally quite different from mainland birds. Their preference for open

forest and forest edge is a habitat quite different from the more open country

taken by the continental populations. Osteological differences have also been

noted and used to suggest species status for Galapagos birds (Steadman 1986).

In summary, various independent lines of evidence can be used to conclude that

there is a different species on Galapagos than the mainland. What is novel is

that the genetic data also clarifies the distinctness of the San Cristobal

population dubius.

Unfortunately, no vocal data is available for dubius, and it may in fact be

extinct now. The branch length separating dubius from the other

Galapagos populations is quite old, suggesting the split is older than any

division seen in the mainland clades. The geographic pattern also fits a

general one seen in the Galapagos, with the old branch (dubius) restricted to the

older eastern islands, in this case San Cristobal. More work is needed to

understand if more than one species is present in nanus, but certainly dubius

appears to be a good species.

Austral migrant rubinus

– There are multiple clades within the mainland Vermilion Flycatchers. Perhaps

there are multiple species level questions to be resolved although nothing

obvious. However, multiple lines of data clarify that the southern migratory rubinus

deserves species status. What is confusing is that the mtDNA data suggest that

it is nested within the mainland group. The nuclear data show a different

pattern where the distinctness of rubinus is perhaps clearer.

There are various reasons why the mtDNA results may be incorrectly showing the

relationship of rubinus,

and on this Carmi et al. (2016) do not

elaborate. The mtDNA data show a sister relationship with the

northern South American group, where rubinus winters. It is not

impossible that historical hybridization with that population may be reflected

in the current mtDNA results and that this may not be its true history? There

is no current evidence for hybridization, and the breeding ranges of rubinus and saturatus do not come close.

The

important point is that the mtDNA do show rubinus to be a separate

clade within the mainland populations. Nuclear DNA further supports

distinctness of this group. But more importantly, the birds themselves show a

clear biological difference, vocalizations. This section was taken out of the

Carmi et al. (2016) paper by the editors. Although sample sizes were low,

playback experiments I have conducted are clear: rubinus does not respond to a

northern song and vice versa. I have more data currently, all of it

unpublished, and the same pattern remains. Furthermore, experiments playing

voice of mexicanus to cocachacrae invoke a response, whereas rubinus is ignored by cocachacrae. The deleted text in the

paper is the following:

“Males

from Belize (subspecies blatteus) were more likely to respond to song from

Arizona males (subspecies flammeus) than to song from Uruguay males (subspecies rubinus;

Wilcoxon signed-rank test W=0, p<0.5, n=10). Males from Uruguay were more

likely to respond to song from Uruguay males than to song from Arizona males

[Wilcoxon signed-rank test W=0, p<0.5, nr=6 (n=9)]. No male from Belize responded to songs from

Uruguay, and similarly no Uruguayan male responded to songs from Arizona .”

The

general nature and pattern of the song is similar in all mainland Vermilion

Flycatchers: a short, rising, and terminally accented trill. The North

American, coastal South American, and northern South American birds have

similar songs. Compared to rubinus they are lower pitched, are delivered more

slowly, and the terminal note is clearly lower pitched than the pitch at the

crescendo of the trill. Here is a typical example: =

https://www.xeno-canto.org/299099

On the other hand, rubinus is higher pitched,

rises quickly and the final note is high pitched, similar to the frequency of

the end of the crescendo. This gives the voice an upwardly accented nature,

quite different from other mainland Vermilion Flycatchers. All can perform bill

snaps during the vocal displays. I have not looked at differences in the call

notes. As noted above, birds of the different song types (rubinus and non-rubinus)

ignore each other’s voice. Given this clear biological response in a suboscine,

rubinus

acts like a good species.

Recommendation:

Based on molecular data, as well as biological (voice)

data, we suggest dividing up the Vermilion Flycatcher into four species: Pyrocephalus rubinus,

Pyrocephalus obscurus, Pyrocephalus nanus, and Pyrocephalus dubius.

Note that rubinus, nanus and dubius would be monotypic. However, P. obscurus would include: obscurus,

piurae, ardens, cocachacrae, saturatus, mexicanus, blatteus, flammeus and pinicola.

English names:

This is

a tough issue as the Vermilion Flycatcher is one of the most widespread and

best known of the Tyrannidae. Although it may be troubling for some to retain

this name for obscurus,

for reasons that have been discussed by this committee elsewhere, in my opinion

the argument for keeping the name is persuasive. Essentially every English

speaker who watches birds in the Americas knows the Vermilion Flycatcher,

changing this name to something else like Northern Vermilion-Flycatcher is

adding complexity to an issue that in the end will create very little confusion

for most people in English-speaking countries. It really is a non-issue for 99%

of the user group of English Names to keep Vermilion Flycatcher even though it

now refers to a subset of what that name used to mean.

I am not

keen on adding a modifier to Vermilion Flycatcher for the various forms and

prefer distinct and evocative names. The easiest of which is to call the

possibly extinct Pyrocephalus

dubius the San Cristobal Flycatcher.

For Pyrocephalus nanus,

the name Galapagos Flycatcher is already taken. In the Galapagos this species

is well known, although it is declining at a precipitous rate. It has become a

conservation concern, and I think to respect what the locals call it, an

evocative name would be Brujo Flycatcher. Locally it is invariably called

“pajaro brujo,” the witch bird. As so many tyrannids have such forgettable

names, why not call the most colorful passerine of the Galapagos by a colorful

name?

Finally, Pyrocephalus rubinus can be

given many names. Perhaps coming up with one that highlights its migratory

tendency, being the only firm migrant within Pyrocephalus is appealing.

But I could not think of any good name that works. I have seen the name

“Scarlet Flycatcher” being used, such as on Xeno-canto. I don’t know if this is

a name they just pulled out of their cloaca or if it has some historical

context? In any case, my preference would be Ruby Flycatcher to match with the

scientific name. Male rubinus are darker than obscurus, a darker red

below and darker brown above. But I don’t think that the color differences are

enough that one could make an argument of ruby or scarlet versus what

vermillion means, essentially, they all suggest a red coloration.

Literature:

Carmi,

O., Witt, C.C., Jaramillo, A. & J. P. Dumbacher. 2016. Phylogeography of

the Vermilion Flycatcher species complex: Multiple speciation events, shifts in

migratory behavior, and an apparent extinction of a Galápagos-endemic bird

species. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 102: 152–173.

DeBenedictis,

P., 1966. The flight song display of two taxa of Vermilion Flycatcher, genus Pyrocephalus.

Condor 68, 306–307. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1365570.

Dickinson

and Christidis (2014). 2014. The Howard and Moore Complete Checklist of the

Birds of the World, fourth ed., vol. 2. Aves Press, Eastbourne, UK.

Ellison,

K., Wolf, B.O., Jones, S.L., 2009. Vermilion Flycatcher (Pyrocephalus rubinus). In:

Poole, A. (Ed.), The Birds of North America Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology,

Ithaca.

Farnsworth,

A., Lebbin, D.J., 2004. Vermilion Flycatcher. In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A.,

Christie, D. (Eds.), Handbook of the Birds of the World, Cotingas to Pipits and

Wagtails, vol. 9. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, pp. 374–375.

Alvaro

Jaramillo, April 2019

Note from Remsen: Voting

structure is as follows:

818A.

Split Galapagos nanus (including dubius) from widespread mainland taxa.

818B.

Treat dubius as a separate species

from nanus.

818C.

Treat all mainland taxa as P. obscurus,

as a separate species from nominate rubinus.

English names (if splits adopted):

818D:

Use separate English names for each species rather than compound names, i.e.

“Something Vermilion-Flycatcher.”

818A-E.

Use “Brujo” as the “first name” for nanus

818B-E.

Use “San Cristobal” as the “first name” for dubius

818C-E1.

Retain “Vermilion” as the “first name” for widespread obscurus

818C-E2. Use “Ruby” as the “first name” for nominate rubinus

Comments from Areta:

“818A. YES to recognizing both Galapagos forms as a

separate species from mainland taxa. The few vocalizations of nanus

I´ve heard are clearly different from rubinus and obscurus,

and the females differ notably from those elsewhere.

“818B. NO, until biological data such as vocalizations (if

not extinct) or more thorough genetic work provides deeper information on the

genetic architecture of dubius. The age of the split between nanus

and dubius

is not impressive, and given that we do not know what this would mean in terms

of reproductive compatibilities, I prefer to recognize dubius as a subspecies of nanus.

Also, note that the difference between the two nanus groups is quite deep in

comparison to that between rubinus and obscurus, yet we are not

discussing their treatment as different species based only on genetic distance.

“818C. YES. I was skeptical of this given the paraphyly of obscurus

with respect to rubinus

(this is something that I would have like explained in the paper itself).

However, after checking all available recordings of songs of the different

taxa, I agree with Alvaro in that the vocal differences between rubinus

and obscurus

(including from mexicanus

to cocachacrae)

are constant. The lack of answer between blatteus and rubinus,

while mexicanus

responds to cocachacrae

seal the deal for me. There is ample room here to publish these playback

experiments together with a thorough vocal analysis of these taxa. It is

regrettable that the comments on vocalizations and playbacks were taken out of

the ms.”

Comments from Claramunt:

“818A: YES. Very complicated case. I think it is fair to tentatively separate

the Galapagos forms as a different species given their plumage, morphological,

and song differences, and the fact that they form a separate mitochondrial

lineage. So, YES to A.

“818B. NO.

Elevating dubius to species mainly because of high levels of

mtDNA "divergence" is not justified, in my opinion. Despite widespread belief, haplotypes with 2%

“divergence” can perfectly coexist within a single species (see Benham &

Cheviron 2019 Molecular Ecology 28:1765–1783). I would like to see more

evidence regarding this potential split. So, NO to B.

“818C. NO. P.

r. rubinus is somewhat distinctive in song and in the fact that it is an

austral migrant but male plumage is barely differentiated and it is not a

different lineage genetically: its mtDNA is part of the south American

continental genealogy, and it shares nuclear alleles, particularly with P.

r. saturatus. Regarding reproductive

isolation, I don’t think that a female of a different subspecies will ignore a

male of rubinus just because he sounds a little different. She may not

react to the song in isolation, but visual cues seem important in this species.

Therefore, NO to C.”

Comments from Stiles: “The genetic data seem quite clear

in mandating splitting up Pyrocephalus

rubinus into SIX species. To begin

with, the name “Vermilion Flycatcher" is solidly entrenched and applicable

to the complex as a whole, as a hyphenated group name - trying to find separate

names that do not include Vermilion seems a bit silly, as any birder anywhere

will recognize a Vermilion Flycatcher! Henceforth,

I will go through the phylogeny as it stands, suggesting E-names en route. 1)

the oldest split is between the Galápagos group and the continental group, so

at the least, one species must be split for the Galápagos, and the internal

split between nanus and dubius is about the same age as the

oldest continental splits, so clearly two species are justified here. Because dubius

apparently is extinct, San Cristobal V-F is appropriate. I see no great problem

with staying with Galápagos V-F for nanus,

as it is now the only extant V-F there but if one must find another name for nanus, Least V-F at least goes with the

Latin name. 2) The next oldest split is between the North-Middle American and

the South American groups, hence at least both must be recognized as separate

species. The former group could be

called Northern V-F (I think mexicanus

has priority as the Latin epithet). 3) The South American group splits into

three well-defined clades of virtually identical ages. If considered as only one species, Southern

V-F would do for all, but if one splits rubinus

from the others, then three species is the only way to go. 4) Very slightly

older is the split between saturatus and the other two.. genetic data are from

Guyana and W Venezuela, but saturatus

also occurs in NE Colombia, so that its distribution is centered on Venezuela,

hence Venezuelan V-F at least does no violence to its distribution relative to

the other two! Carib V-F could be an alternative. 5) From northwestern Colombia

to SW Peru occurs obscurus (originally named for the localized

melanistic form from C Peru, so forget "Dark V-F" as a useful

option!) Hellmayr's name of Pacific V-F fits pretty well. 6) Finally, nominate rubinus, as the southernmost taxon and

an austral migrant, could be called Austral V-F. As a final comment, I can see

no sense in including the northern group under obscurus, producing a flagrant paraphyly. The song of the

southernmost member of the obscurus

group, cacachorea, may show some

resemblance to that of the northern group, but must have been derived

independently; I regard any resemblance as coincidental, or perhaps the

resurfacing of an ancestral character (seems less likely).”

Comments

from Robbins:

“At a minimum, at least two species should be recognized, Galapagos and

mainland based on the differences in vocalizations and genetics. Genetic data support a mainland split into at

least two species, North and South America.

Based on genetic data and the time axis, if one recognizes North and

South America as different species, then one should also recognize Galapagos dubius as a species. Given the three

options we have been presented, for now, I vote as follows:

“818A. YES.

“818B. YES, based on

comments above.

“818C. NO, for

now. I do support recognizing

North/Central American birds from South America, but recognize that is beyond

the scope of our committee. However, depending on member’s viewpoint, that

element may be important for being consistent on how SACC members vote on the

proposals at hand.”

Comments

from Pacheco:

“The multiple data

available are compelling to separate the Galapagos taxa from those on the

Continent. However, for the reasons listed by Nacho and Santiago, I also prefer

to maintain nanus associated subspecifically with dubius. Agreeing with Nacho, I am particularly

impressed by the constant vocal distinctions between the northern taxa and that

southern (nominate) migratory taxon in the continental bloc. Therefore, my votes are: 818A – YES; 818B –

NO; 818C – YES.”

Comments from Remsen: “A. YES.

All lines of evidence point to species rank, as summarized in the

proposal.”

Comments from Bonaccorso:

“818A. YES. All available evidence (molecular,

song, plumage, osteology) point towards a distinct species.

“818B. NO. Agree with Santiago. Genetic distance

and structure should not be the only criteria for species status.

“818C. Abstain. Neither tree topology nor

nuclear networks show a different enough clade. Also, based on tree topology

only, it will seem odd to call P. rubinus a species and lump all other

subspecies into P. obscurus (then P. obscurus will be

paraphyletic). On the other hand,

migratory species are different in the way they speciate (they may cause

paraphyly on the tree). So, it would be

important to publish those song and playback records and do proper analyses, in

order to make a better-informed decision.”

Comments

from Stotz:

“A. “YES to splitting

Galapagos populations from mainland populations. They separate out genetically, vocally and morphologically.

“B. NO to splitting Pyrocephalus

dubius. This taxon is part of a clade with the rest of the Galapagos

birds. Without some sort of data to

suggest species status, I think this is best treated as a part of a Galapagos

endemic species.

“C. NO to splitting obscurus

from rubinus. The vocal

information is very suggestive, but is not published and conflicts with the

published genetic information. I think I

need to see either more information or a clearer statement of the argument

accounting for the distributional and genetic inconsistencies.

“D. “NO. I think I am with Gary on this. While I generally prefer not to create new

compound names, the fact that Vermilion Flycatcher is a very distinctive

flycatcher with a distinctive and good descriptive name, I would like to hang

on to Vermilion Flycatcher for the whole group.

Brujo Flycatcher seems like a mistake.

There is no geographic or descriptive information in it, and Brujo is not

an English word. Ruby Flycatcher is not

too bad, but feels like we are forcing it.

One problem with using Galapagos Vermilion-Flycatcher, given the way the

voting is going, is that then we need a name for the entire mainland

group. Only thoughts I have for that are

Mainland Vermilion-Flycatcher or Common Vermilion-Flycatcher, neither of which

are great names (although HBW uses Common Vermilion-Flycatcher). My guess is that this is a short-term problem

because I expect that we will eventually have sufficient data to split up the

mainland forms into multiple species.”

Comments from Zimmer:

“A. YES. I agree with Mark that

this is the minimum that we should do, based upon concordant vocal,

morphological and genetic data that appear unambiguous in supporting a split of

all Galapagos populations from all mainland populations.

“B. NO. Without more data, I’m

inclined to treat this taxon as a subspecies and part of a single clade of

Galapagos birds specifically distinct from mainland birds, particularly given

that there is geographic structure to the genetic data even within nana populations.

“C. YES. I’m more than a little

confused as how to proceed on this, given the limitations of how 818C is

worded. I agree with those who see a

clear North/Middle American versus South American split, so I don’t feel that

lumping all mainland forms into a paraphyletic obscurus, separate from nominate rubinus is the way to go.

And I definitely don’t support keeping all mainland populations (from

North America to South America) together in rubinus. In looking at the clades supported by the

data, and with biogeographical considerations in mind, my gut tells me that

Gary’s approach is probably the correct one with respect to mainland

populations: 1) North & Middle

American birds (flammeus, blatteus, mexicanus, pinicola) as one species; 2)

Pacific Coast of South America populations (piurae,

ardens, obscurus, cocachacrae) as another; 3)

Northern South America populations (saturatus)

as a third; and 4) migratory Austral populations (rubinus) as a 4th, with Galapagos populations (nanus & dubius) representing a 5th

species. This approach does not fit

within 818C as currently constructed, unless one views the separation of a

paraphyletic obscurus from rubinus, as a necessary first step to

further splitting. With that in mind,

I’ll vote YES, based on the vocal distinctions of rubinus from everything else

(including the results of reciprocal playback trials, which, unfortunately,

were edited out of the paper), just to get the ball rolling, and to pave the

way toward further splitting. I agree

with both Gary and Doug that using “Vermilion-Flycatcher” as an English group

name (to be paired with a species-specific modifier) is the way to go, in what

is a demonstrably monophyletic group.

But that would be putting the cart before the horse, since we don’t yet

know which way the committee will go with respect to the number of splits. If I am understanding Van’s instructions

correctly, we will vote on English names once/if the splits are adopted, but

not until then.”

Additional comments from Stiles: “Taking a closer look at

the topology of the genetic results, I note that the branch separating

saturatus from rubinus + obscurus is extremely short and not all

that well supported, such that the relationships of these three taxa almost constitute

a polytomy (calling into question whether the supposed polyphyly of obscurus

if including saturatus really exists). Hence, I think that the most reasonable course

for now is to include all three under rubinus, and await more conclusive

evidence for their relationships. It therefore means that "Southern

V-F" will do for the E-name, at least for now.”